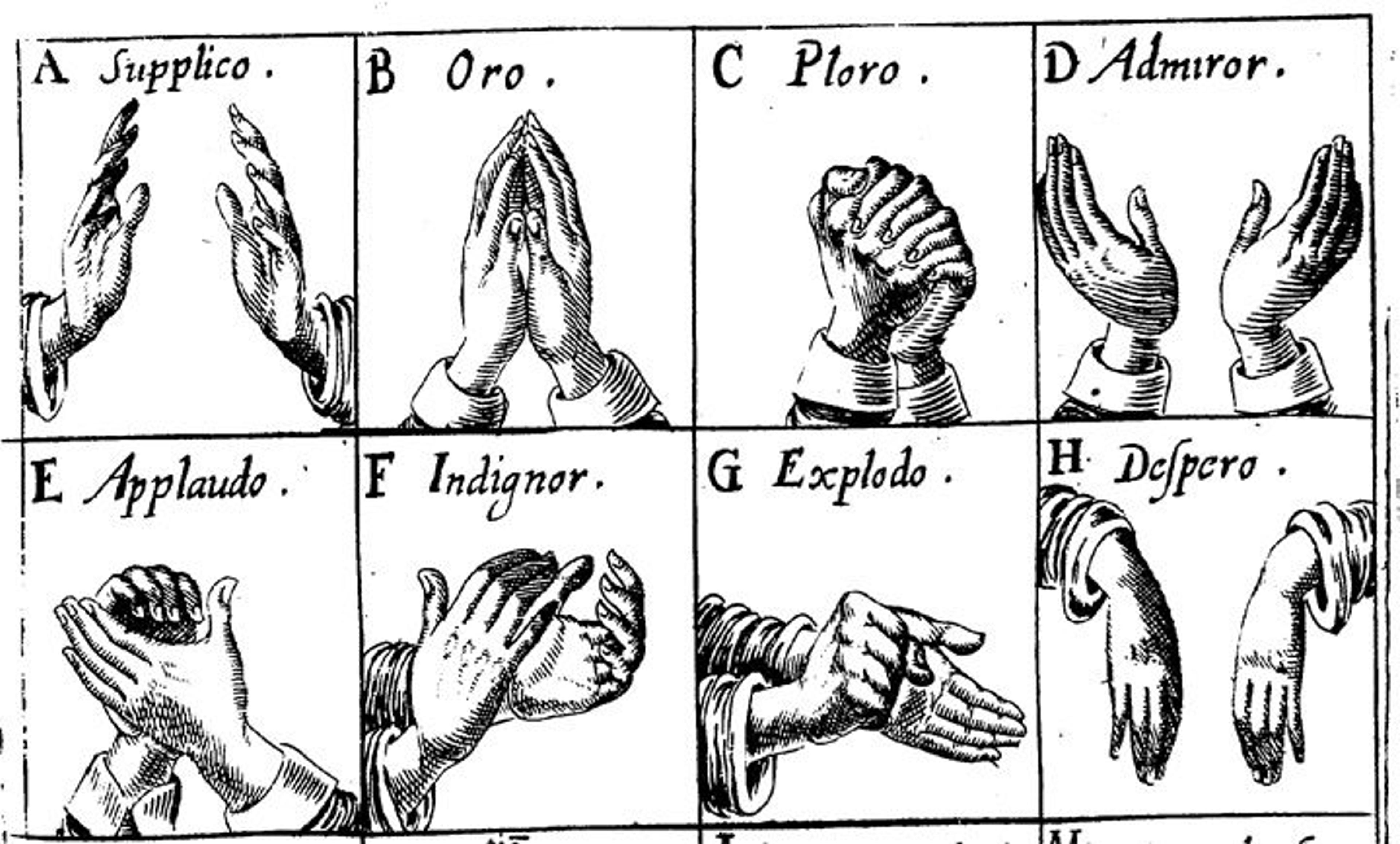

Illustration from John Bulwer's Chirologia, or the Natural Language of the Hand (1644)

«When we think of Caravaggio, we think of dramatic lighting and figures that seem to have stepped right out of the Roman streets. More often than not, however, the subjects of his works were religious and meant to present a moral drama—and one of the means of doing that was with gesture.»

We all know that Italians are famous for gesticulating, but deciphering those gestures can be baffling. Various treatises were written about the subject throughout the 17th century, including one by John Bulwer, Chirologia, or the Natural Language of the Hand, written in 1644. This was no casual enterprise but was based on the study of formal gestures—not the gestures of the street, but those sanctioned by the authority of Roman Classical treatises such as Cicero's De oratore (55 B.C.). Shown above are some examples of the illustrations for supplication, prayer, imploring, and admiring, among others.

In Chirologia, Bulwer states that "to beat and knock the hand upon the breast is a natural expression . . . used in contrition, repentance, shame, and reprehending ourselves." That's just what is happening in Caravaggio's The Denial of Saint Peter, in which the apostle Peter denies to two accusers that he was a follower of Jesus.

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (Italian, 1571–1610). The Denial of Saint Peter, 1610. Oil on canvas, 37 x 49 3/8 in. (94 x 125.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Herman and Lila Shickman, and Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997 (1997.167)

Look at his face, with the brush describing that furrowed brow and the eyes filled with remorse at his own betrayal. It's one of Caravaggio's final paintings and, beginning on April 10, it will be reunited with another of his late masterpieces, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, which is being lent to The Met by the Banca Intesa Sanpaolo in Naples for display in an upcoming exhibition, Caravaggio's Last Two Paintings.