The Potala Palace, with the city of Lhasa in the foreground. Construction of the palace began in 1645.

«As mentioned in a previous post, I conducted two survey trips in preparation for the exhibition Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations (on view through June 8), which focuses on eleventh- and twelfth-century connections and interactions between the Buddhist communities of Tibet and India. My trip to central Tibet in September 2010 allowed me to visit and study many of the extant Buddhist monasteries there, and to survey the wall painting preserved in monastic sacred structures.»

I began in Lhasa, as I needed to get acclimated to the 12,000-foot altitude before going even higher in other parts of Tibet. Not surprisingly I started with the spectacular Potala Palace and the many sculptures and objects in its collections. I then moved on to important sites in the city and in the surrounding mountains.

Prayer flags above the Drak Yerpa monastery outside of Lhasa

The most important pilgrimage sites across Tibet are often linked to sacred places, especially caves where great teachers meditated, as is the case with the Drak Yerpa complex above Lhasa.

Portrait of the Indian Monk Atisha. Tibet, early to mid-12th century. Opaque watercolor and gold on cloth. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of The Kronos Collections, 1993 (1993.479)

One of the important teachers said to have meditated in Drak Yerpa valley is the Indian monk Atisha, who in 1042 came to Tibet at the invitation of the western Tibetan king Yesh 'Od. This tangka (painting on cloth) made in the early to mid-twelfth century—several generations after Atisha's death in 1054—is the earliest known portrait of this great master.

Lake and mountains on the road to Gyantse

Next I headed to Gyantse. Strong storms had washed out bridges on the regular route, so I crossed via a high pass through the mountains.

View of a mountain on the way to Gyantse

The mountains of the Himalayas are amazing and dramatic, as is the open countryside of the high Tibet plateau. In this sense the temples of Tibet are just one part of a vibrant setting.

Gyantse Kumbum, which was founded in 1427

The Gyantse sacred area is dominated by the Kumbum; a stupa-like image temple that takes the form of a three-dimensional mandala. Within the seventy-seven small chambers that encircle the structure are many elaborate paintings.

This green Tara from the interior shrine of Gyantse Kumbum dates to after 1427 and is approximately six feet tall.

The monument is structured so that a worshiper walking around and up onto the monument encounters a sequence of images. One begins with auspicious deities of protection and abundance, like the green Tara shown above.

Mahakala, Protector of the Tent, ca. 1500. Central Tibet, Sakya Order. Tangka; gouache on cotton. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Zimmerman Family Collection, 2012 (2012.444.4)

Like the wall paintings in the Kumbum, the Mahakala painting shown above reveals many characteristics that suggest the work of Nepalese artists. In this instance the serrated flaming halo is a distinct characteristic shared with the Kumbum wall paintings.

Gyantse Kumbum. This mandala in the upper shrine, which is approximately ten feet tall, dates to after 1427.

The imagery gets increasingly more complex toward to the top and center of the Kumbum. Ultimately one encounters a whole series of massive and complex mandalas that comment on the very nature of transcendent enlightenment. The power of these colorful and intricate compositions, which would have been seen by the light of butter lamps in dark chapels, is made all the more profound by their juxtaposition with Tibet's vast dramatic landscape.

Mountains surrounding Gyantse

After working with the great concentration of wall paintings at Gyantse, most of which date to after the fifteenth century, I went onto the city of Shigatse and visited the nearby Shalu monastery.

Shalu monastery, founded 1040

In terms of thinking about the exhibition, which focuses on art produced in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the wall paintings preserved in Shalu monastery were of great importance.

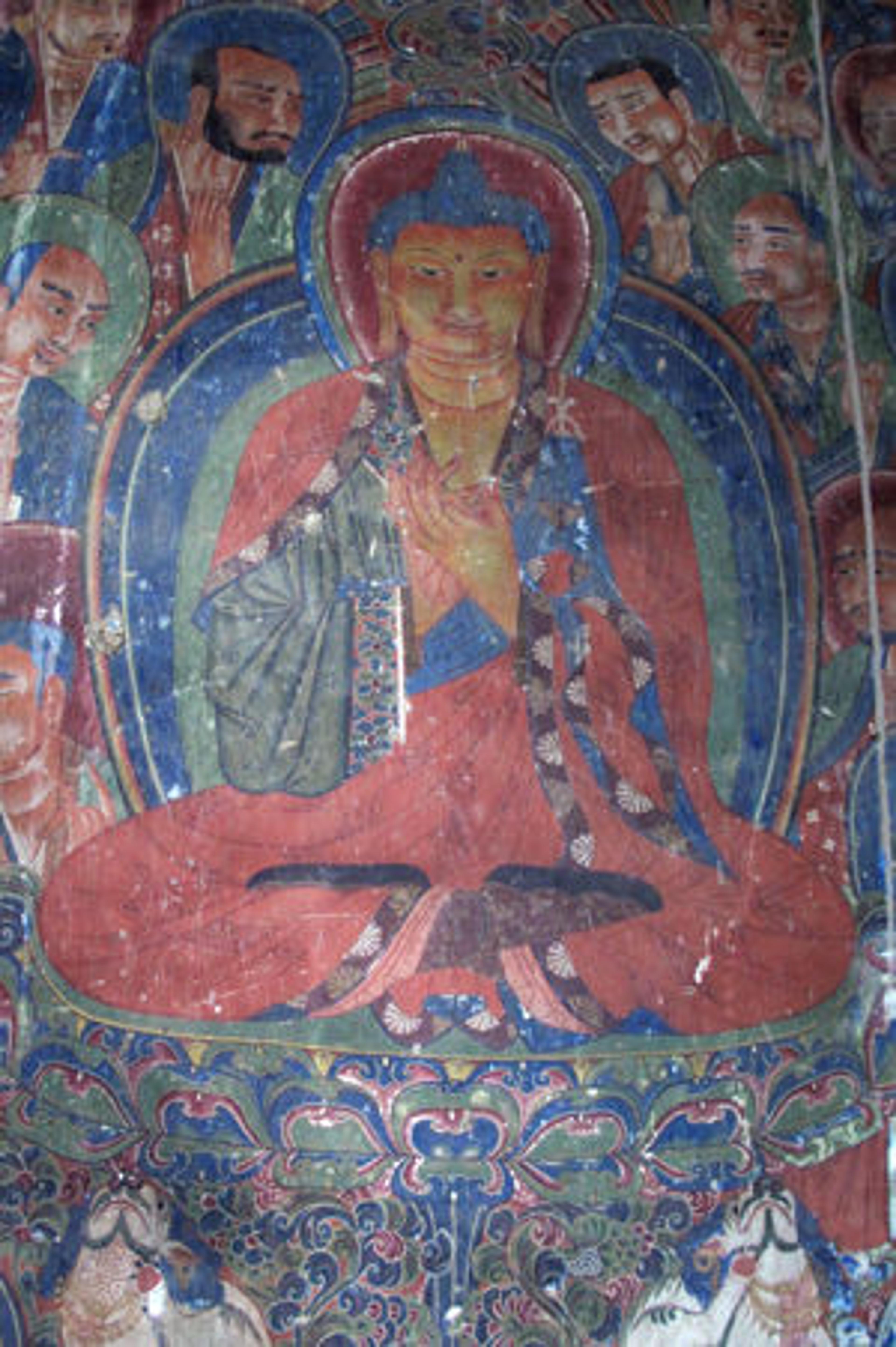

Shalu wall painting of the Buddha Akshobhya, completed after 1306

Atisha visited this complex in the mid-eleventh century, and the wall painting here reflects an interest in the Mahayana ideology of that time. Particularly important was the veneration of celestial Buddhas that were understood to inhabit pure lands in each of the cardinal directions. For a worshiper, these Buddhas were especially appealing—through devotion one could hope to be reborn in one of these pure lands, which in turn would give one access to the uncorrupted Buddhist teachings (dharma) from a living Buddha. Ultimately this form of Buddhism offered a clear path to enlightenment.

Fortified tower of the main complex at the Sakya monastery, founded 1073

Another site that dates to about this period is the Sakya monastery, where again many early paintings survive. The idea of fortifying a monastic enclosure probably has its roots in India and Central Asia, but was also important in Tibet. In this instance, Sakya sits at the entrance of an important pass through the Himalayas.

Drathang monastery, founded 1081

Another site with early wall painting is the Drathang monastery, southeast of Lhasa.

Drathang Buddha with his hands in the Dharma Chakra mudra, ca. 12th century

Here the murals follow a different stylistic lineage. Ultimately the diversity of styles and iconography present in twelfth-century Tibet indicate that many workshops were active.

Buddha Amitayus Attended by Bodhisattvas. Tibet, 11th or early 12th century. Mineral and organic pigments on cloth. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1989 (1989.284)

Though stylistically distinct, this painting of the Buddha Amitayus can be related to the Drathang wall painting. Amitayus is here shown as a massive, introspective figure sitting in a perfect state of meditation. He wears a jeweled crown with fluttering ribbons, and his many necklaces, bracelets, and luxurious textiles emphasize his radiant yellow body, which sparkles in the light. (The shimmering surface particles, which look almost like mica, were not part of the original composition; they appeared over time as arsenic crystals formed from the orpiment pigments used for the bold yellow coloring of the body.)

The refinement and quality of the paintings from this period speaks to active patronage and the vitality of the Tibetan Buddhist communities.