In 2021, The Metropolitan Museum's Imaging Department, under the direction of Scott Geffert, successfully measured the sphinx of the Greek funerary monument of Megakles in three dimensions with great detail using photogrammetry. This data was processed by Ralf Deuke in Munich and passed on to the company Voxeljet in southern Germany, where the sphinx was built in two components made of Plexiglas powder (polymethylmetacrylate) in their 3D printers. Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann carefully added to this copy at selected minor breakage points and then covered it with several superfine layers of marble stucco and smoothed it. The result of this collaborative effort, a likely reconstruction of the sphinx in its original form and color, is on view in the special exhibition Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color.

Reconstruction in process: Partial casts are used to test the skin color measured in UV-Vis, but also controlling the shaping of the eye elements.

To recreate the armature of the feather patterns on the breast and wings of the sphinx, as well as the application of the colors themselves, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann and Vinzenz Brinkmann’s team relied on rich scientific findings by The Met’s Imaging team, including multispectral photographs by Dorothy Abramitis, as well as ultraviolet-visible absorption spectroscopy (UV-VIS) by Heinrich Piening, which were supplemented by further photographs in ultraviolet (UVL) and infrared (VIL) fluorescence and false color (iDStretch app) captured by Vinzenz Brinkmann.

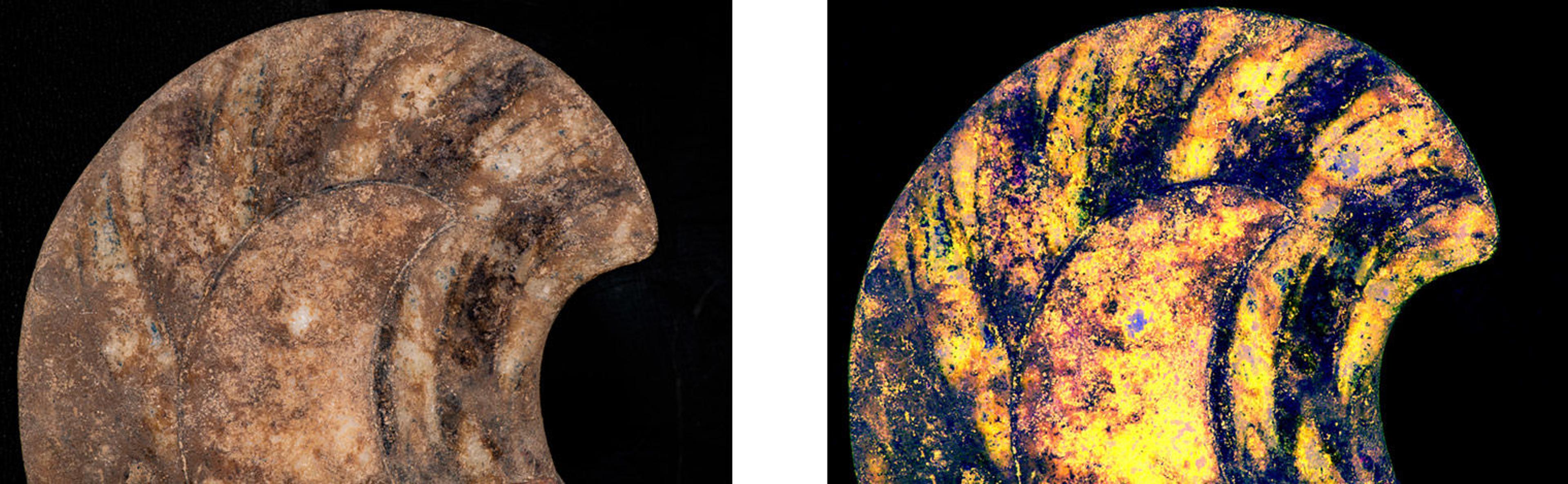

Left: Scale-shaped feathers on the chest. Right: Scale-shaped feathers on the chest in false colors. Images courtesy Vinzenz Brinkmann

Since the early 1980s, Vinzenz Brinkmann has examined numerous Archaic-period marble sphinxes in Greek museums—including the Acropolis Museum of Athens, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, and the Corinth Archaeological Museum—with the help of multispectral photography, microscopy, and raking light, as part of a larger research project. In addition, the Liebieghaus team also investigated representations of the sphinx in other visual media dating to the sixth century B.C. This extensive analysis of archaeological and art-historical comparanda offered a significant data pool that complemented the scientific and photo-technical examinations of the original, enabling a more complete reconstruction.

Left: Long feathers on the tip of the front wing. Image courtesy Vinzenz Brinkmann. Right: Long feathers on the tip of the front wing in false colors.

In a next phase, the color shades used on the original were recreated. This was based on the visual examination, the extensive scientific analyses of The Met’s research team, and also measurements of the precise color space of the areas with well-preserved pigment residues by Heinrich Piening. Using these results, pigments that fully corresponded to the ancient materials in different hue or color variants were mixed and applied to marble stucco test panels. Finally, the color aspect or value of these variants was also measured to find the closest match.

Application of cinnabar pigment on the scale-like breast feathers, after the outline of the feathers has been painted with yellow ocher into a pre-drawn grid. Image courtesy of Vinzenz Brinkmann

Over the course of three months, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann applied the determined color values, which we believe represent the closest possible match to the original, to the copy, each in several layers. The UV-VIS Absorption Spectroscopy, carried out by Heinrich Piening, was able to provide precise information about the skin color of the Sphinx on the face and neck. According to this, the skin color consists of lead white mixed with yellow ocher and hematite. Skin color had been identified on other archaic Greek sculptures: the excavators of the Athenian Acropolis, for example, reported at the end of the nineteenth century that the archaic marble sculptures they unearthed still showed remnants of skin color at the moment of their discovery. The ocher-yellow fur color could also be determined in this way. Comparisons with better preserved color remains of the fur on a sphinx in the National Museum of Athens and the representation of the lion's fur on Egyptian sphinxes corroborated the team’s scientific analysis.

The central sections on the faces of the two wings, the front and back surfaces, presented a particular challenge in the reconstruction. While the traces of paint on the flight feathers are particularly well preserved, the central sections on both wings were apparently not colored with pigments or colorants at any time. No traces were observed in these areas, despite the generally very good preservation of the marble surface. On the other hand, this central area is defined by a precise incision in the marble. Similar narrow grooves have been used to affix metal foil to classical-period bronze sculpture. The narrow grooves on a bronze sculpture from the Athenian Agora (the head of a goddess of victory or fragments of an equestrian figure, for example) still show the hammered-in remains of a gilded-silver foil. Following these observations, we reconstructed a corresponding gilded sheet in the central zone of the front wing of the sphinx, which—in direct accordance with large-scale representations of sphinx wings in archaic Greek vase painting—has been provided with small scale-like feathers.

While in some cultural contexts, in particular Egypt, the sphinx was represented as male and did not integrate the features of a bird, Greek artists were influenced by Near Eastern art in their rendering of female sphinxes. A review of all the accessible comparative material provided examples of double volute head ornaments in representations of sphinxes in Greek Archaic vase painting. A similar headdress, probably derived from symbols of gods or kings, is found on depictions of sphinxes in earlier Phoenician or Syrian art. The original New York sphinx preserves a bent fragment of a bronze pin that was originally oriented straight up and secured in a drilled hole by molten lead.

But there are challenges to these recreations. The well-preserved paint allowed for an accurate approximation of the original appearance of this sculpture. It is possible, however, that detailing within those individually colored areas, such as that of the scale feathers, may once have been present and are now completely lost.