Afrofuturism is a genre that centers Black history and culture and incorporates science-fiction, technology, and futuristic elements into literature, music, and the visual arts. Often using current social movements or popular culture as a backdrop, Afrofuturism focuses on works that examine the past, question the present, or imagine an optimistic future, and are meant to inspire a sense of pride in their audience.

Watson Library has collected books on Afrofuturism for years, though they may have been under the guise of speculative arts, surrealism, fashion, or even comics and graphic novels. But in the past two years, we have made a more concerted effort to collect and identify books by and about African American artists, and we were also inspired by the opening of Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room in 2021 to include more books on Afrofuturism in our collection. Here is a selection of some of those books.

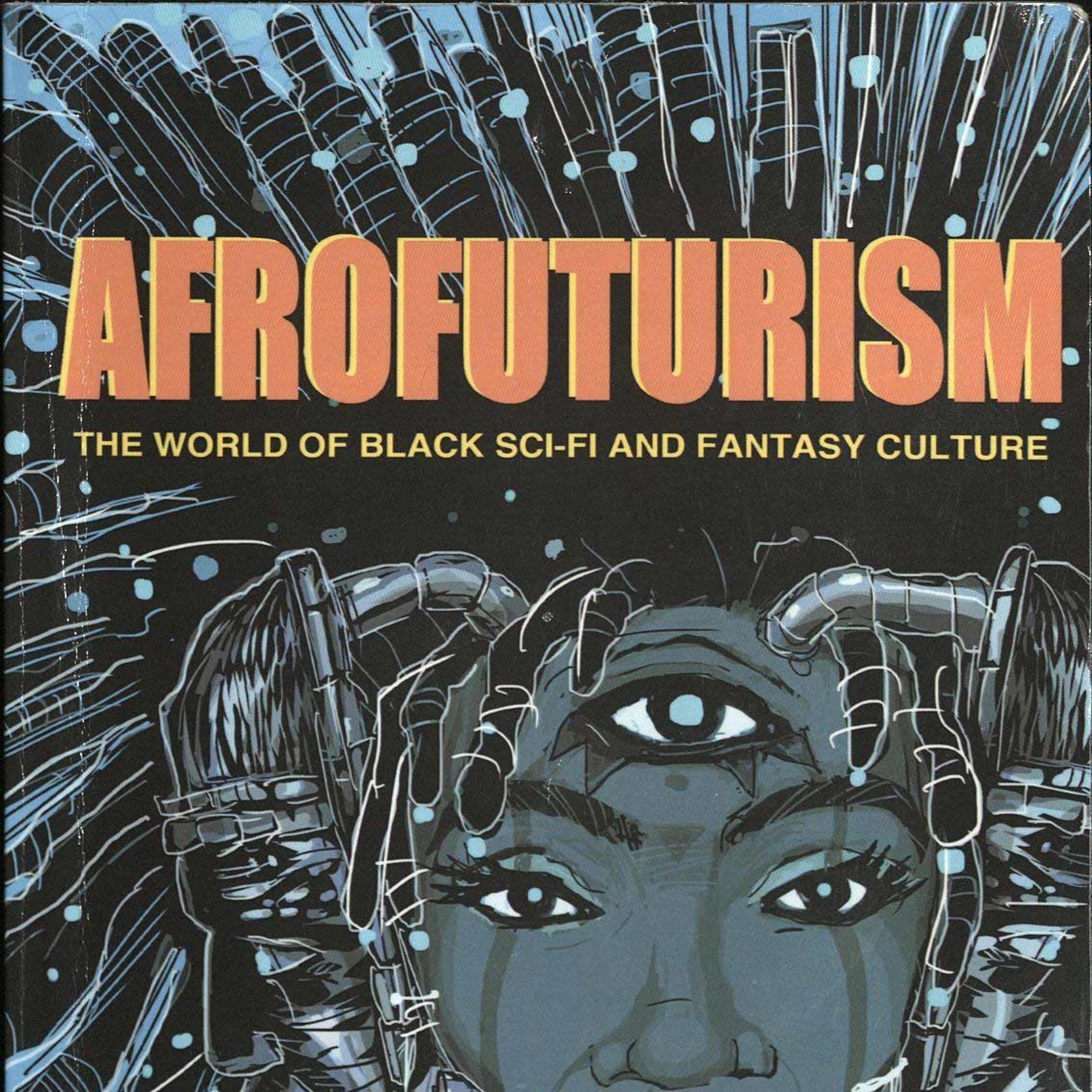

The term “Afrofuturism” was introduced by scholar Mark Dery in 1993, as a way of defining existing trends that focused on Black literature and 1980s technoculture. But Afrofuturist tendencies have been a part of art, literature, and music almost since the birth of modern science fiction at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In the book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture, Ytasha Womack traces the history of the genre, looking at why Black artists, musicians, and writers have been drawn to the speculative in their works. She also examines what attracts the audience for Afrofuturist art, literature, and music. Afrofuturism is not just about creating imagined worlds; it can also offer an escape from real-world troubles or can be used as a way of examining the problems that African Americans currently face in the world.

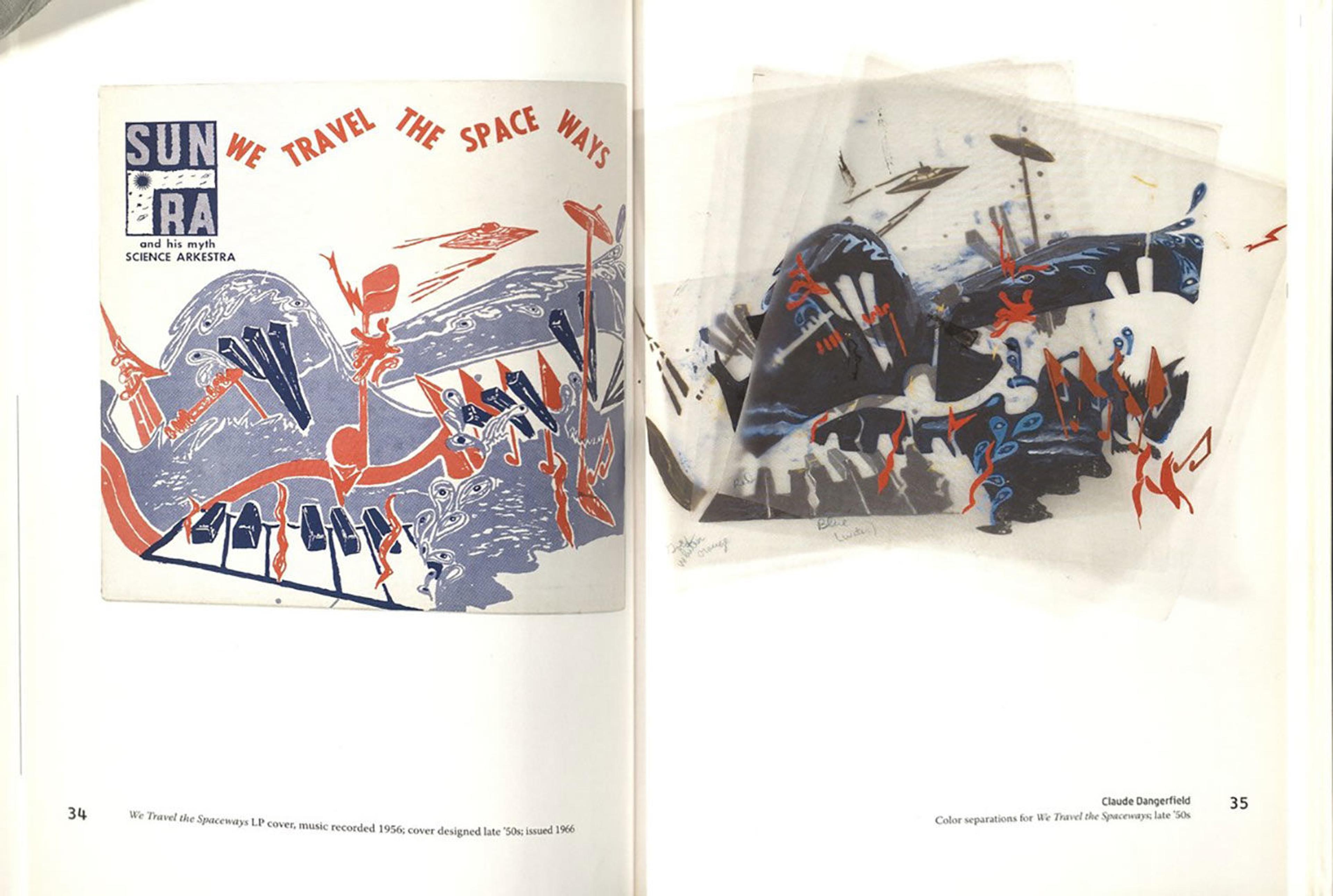

John Corbett, Anthony Elms, and Terri Kapsalis, Pathways to Unknown Worlds: Sun Ra, El Saturn and Chicago’s Afro-Futurist Underground 1954–68 (Chicago: WhiteWalls, 2006)

Avant-garde jazz musician, composer, poet, and artist Sun Ra (born Herman Poole Blount) claimed that he took a trip to Saturn and returned to Earth with a mission to use music to heal and to help people transcend oppression. Originally from Alabama, Sun Ra moved to Chicago and worked in the music and activist communities there during the 1950s. Seeing connections between ancient Egypt and the emerging Space Age, he took his name from the Egyptian sun god and used a mixture of Egyptian and space imagery in his costumes. He created his own label—Saturn Records—using associates of his “Arkestra” to design album covers such as this cover for “We Travel the Spaceways,” designed by Claude Dangerfield. In addition to his music, Sun Ra’s Afrocentric appearance helped influence countless performers over the years, from Earth, Wind & Fire and Parliament/Funkadelic in the 1970s to Solange and Janelle Monáe today.

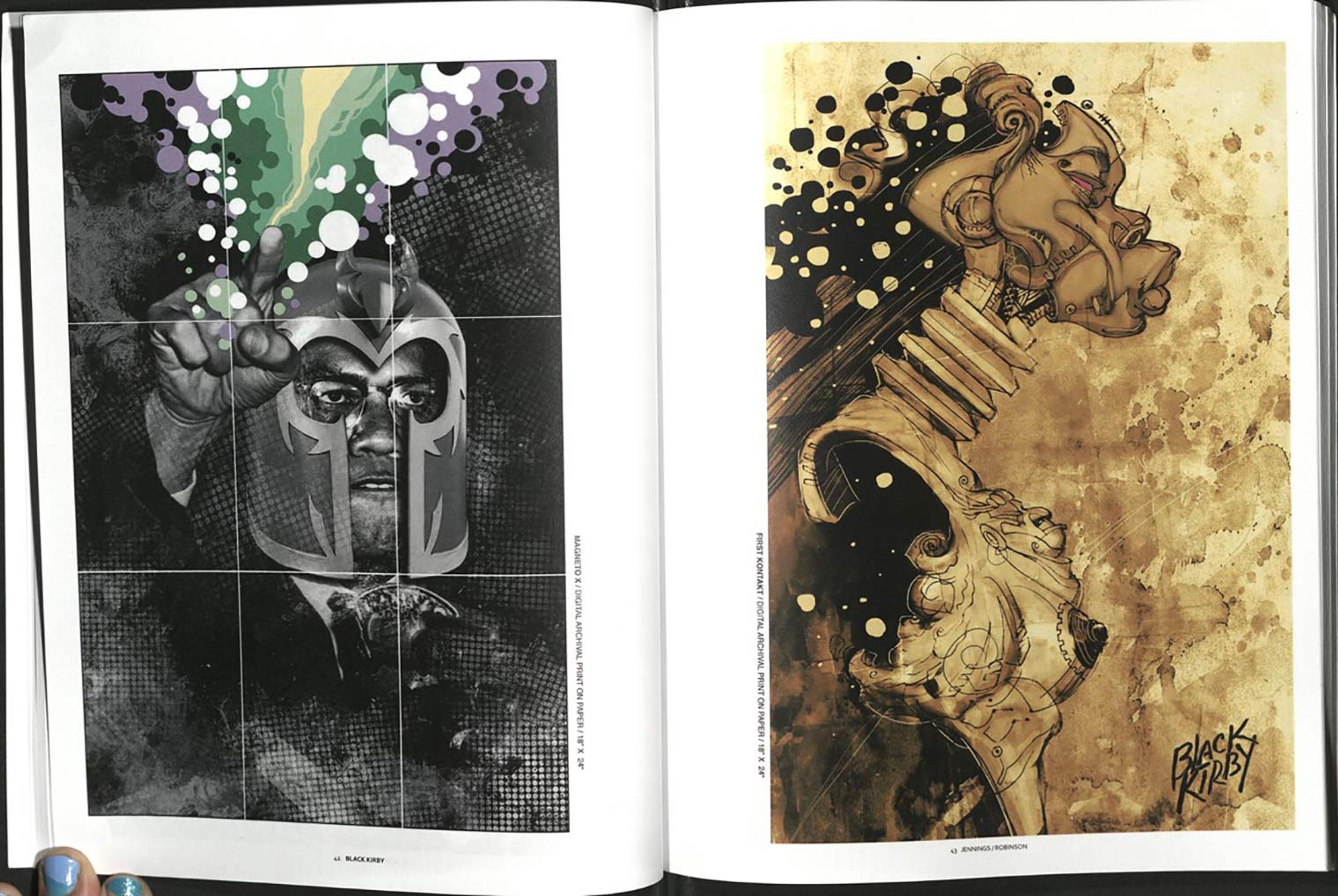

Comic books and graphic novels have played a central role in the development of the Afrofuturism movement. Many of today’s artists grew up reading comics and incorporating the visual style of comics in their works. The fantastic tales and supernatural characters overcoming all odds that are frequently found in comics also appeal to the Afrofuturist spirit of hope through adversity.

Black Kirby Presents: In Search of the Motherboxx Connection (Buffalo, NY : Black Kirby Collective in association with Eye Trauma Studio, J2D2, Urban Kreep Enterprises and Trimekka Studios, 2013)

“Black Kirby” is the name of the artist duo Stacey Robinson and John Jennings. Jennings also wrote and drew the minicomic that is in the Met Bulletin for the Afrofuturist Period Room. Black Kirby “remixes” the classic style of comic-book artist and writer Jack Kirby (creator of Marvel Comics superheroes such as Captain America, the Avengers, and the Black Panther) into their own characters and create tales with Afrofuturistic themes. Sometimes, the influence of Jack Kirby is direct, as in the picture (above left) of Malcolm X with the helmet worn by Kirby’s X-Men character Magneto—both were leaders of an oppressed class working to end that oppression “by any means necessary.” Meanwhile, “First Kontakt” (above right) examines broader themes with an android whose features reflect her African ancestry. Is this simply a mashup of the past and the future, taking the concept of humanity’s first contact with aliens and harkening back to our African origins on earth? Or is it referencing the dehumanization of the African diaspora after “first contact” with Europeans?

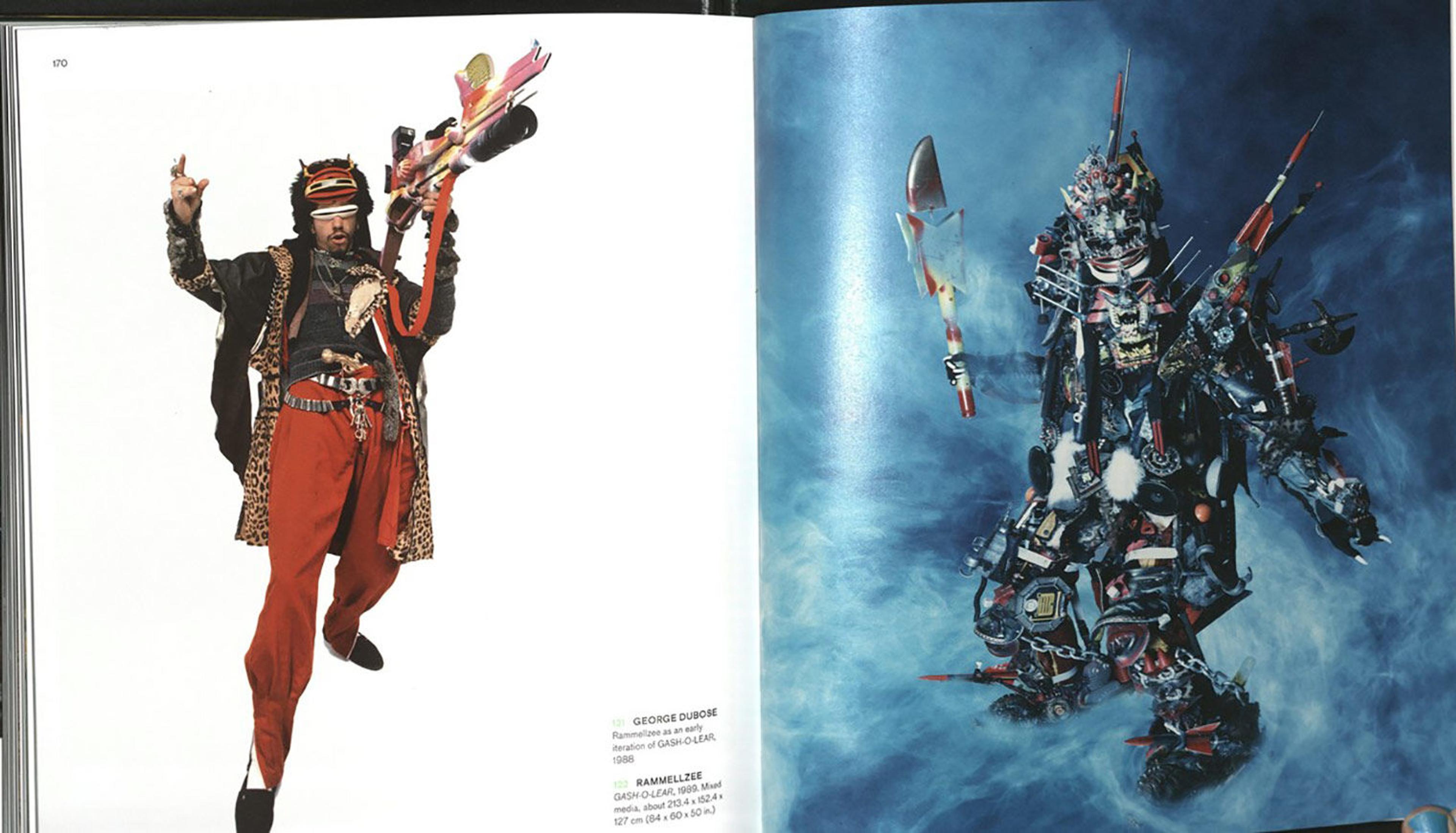

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation (Boston: MFA Publications, 2020)

As with comics, street art is another genre popular among Afrofuturists. RAMM:ELL:ZEE (Rammellzee) was a graffiti artist who got his start on the New York City subways but moved into the realms of painting, hip-hop music, and performance art. He was fascinated with the formation of letters and mathematical equations, and he believed there was a connection between fourteenth-century gothic script and his late-twentieth-century “WildStyle” graffiti. His unique character Gash-o-Lear (above), which first appeared as a sort of cosplay and eventually became a mixed-media form, shows the influence of Star Trek, contemporary hip-hop fashion, and Japanese robot anime. (Anime and manga are also strong influences among Afrofuturist artists.) Rammellzee was also friends with Jean-Michel Basquiat, and this exhibition catalogue, from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, shows the ways that Basquiat was influenced by Rammellzee, other street artists, and the hip-hop movement in the 1980s and ’90s.

The Shadows Took Shape (New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2013)

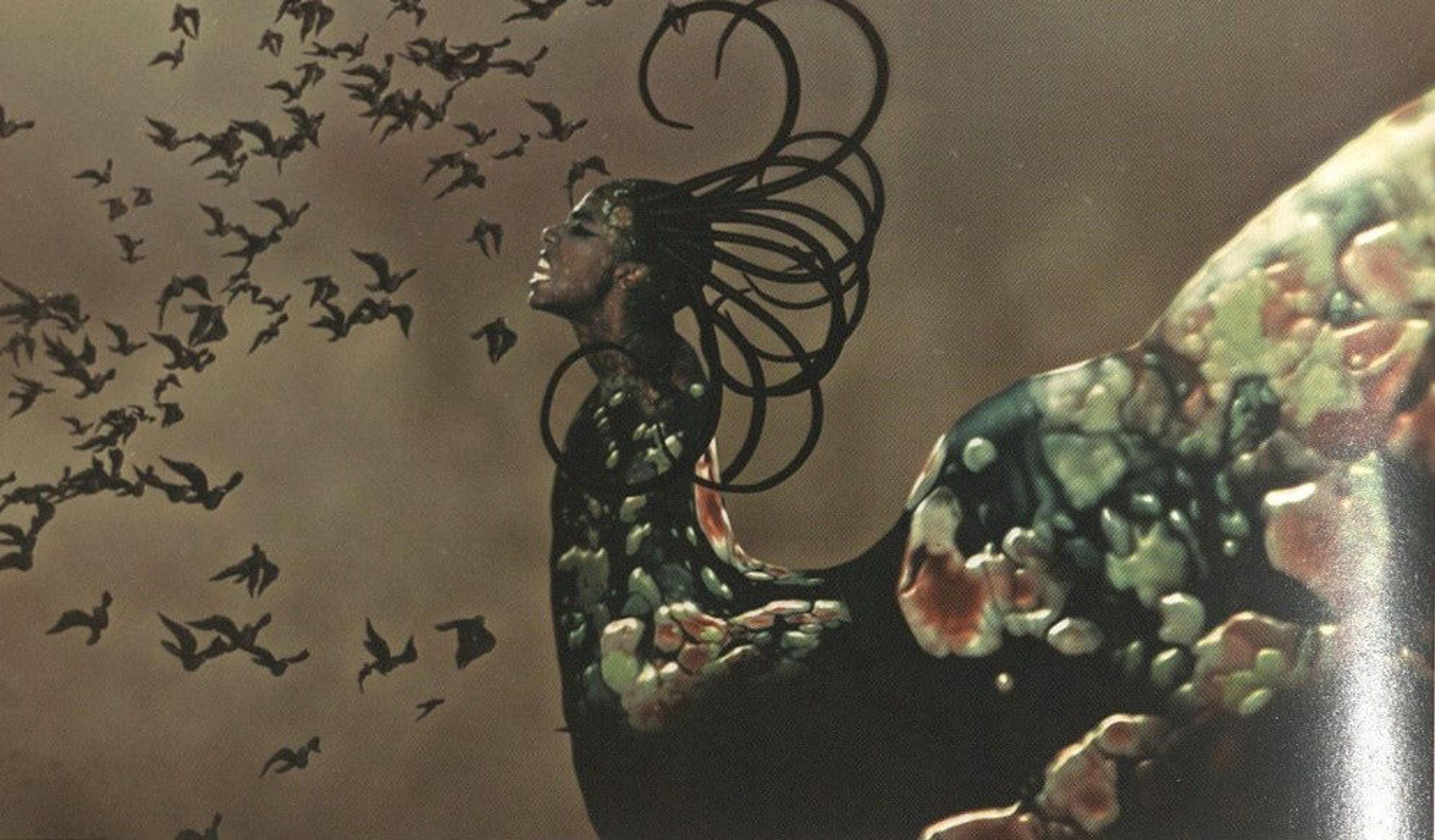

Taking its title from a poem by Sun Ra, The Shadows Took Shape was an exhibition at the Studio Museum of Harlem that examined the global impact of Afrofuturism. Curator Zoé Whitley defines Afrofuturism as, “... an aesthetic strategy for addressing the experience of race, displacement, and difference using recognizable visual symbols.” While Afrofuturism is often seen as centered on the experiences of African Americans, Black people around the world have adopted many of the concepts presented by Afrofuturism and are making connections to their specific lived experiences in the diaspora. Wangechi Mutu uses a caryatid—a sculpted female figure common to both African art and Classical Greek art—in The NewOnes, Will Free Us, a 2019–2020 exhibition that recently graced The Met’s facade. The End of Eating Everything (2013) is a video work featuring a Medusa-like figure representing consumption and material desire that also recalls the East African mythical figure of nguva, a mermaid or siren-like creature.

Cosmic Underground: A Grimoire of Black Speculative Discontent (San Francisco: Cedar Grove Publishing, 2018)

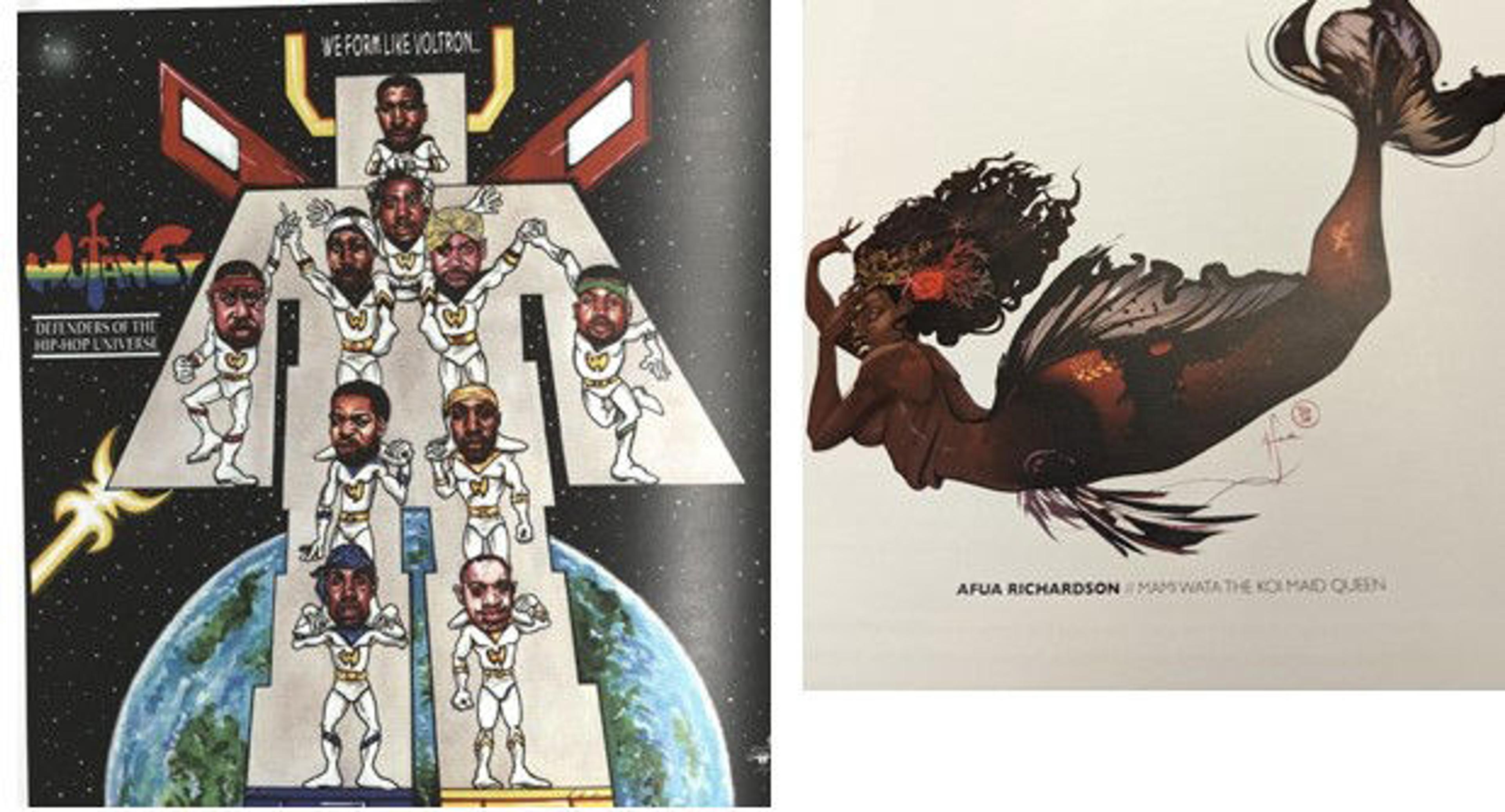

Growing out of a project meant to present Afrofuturistic art during a period of intense political and social unrest in the early 2010s, Cosmic Underground: A Grimoire of Black Speculative Discontent is an anthology of writers and artists expressing their views of the world at the time. Eventually this project grew into what is now known as the Black Speculative Arts Movement (sometimes called “Afrofuturism 2.0”) and encompasses not just science fiction and technology, but also design, metaphysics, and folklore, and includes people from across the African diaspora and an array of influences. In the classic anime Voltron, a giant fighting robot is formed from multiple smaller human-powered robots, and Andre Leroy Davis’s “Wu=Tang Assemble” (above left) shows the hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan assembling as “Defenders of the Hop-Hop Universe.” On the right, Afua Richardson also looks at the sea creatures from African folklore in “Mami Wata the Koi Maid Queen.”

Cosmic Underground: A Grimoire of Black Speculative Discontent (San Francisco: Cedar Grove Publishing, 2018)

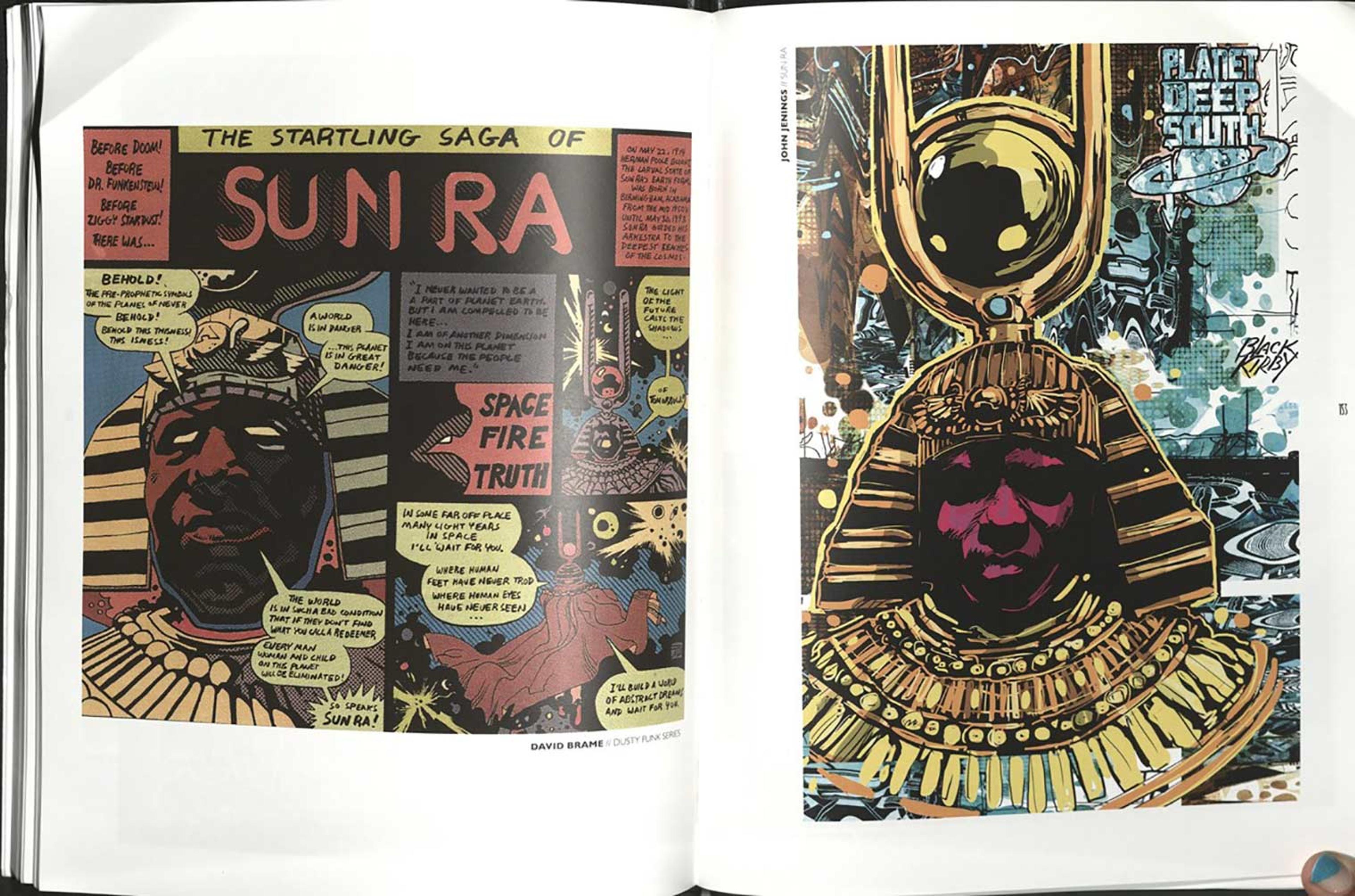

Afrofuturists frequently acknowledge their ancestors and illustrate the ways that the past is a continuing influence on the present, as in these two images from Cosmic Underground that pay tribute to Sun Ra and his impact on Afrofuturism. On the left is the story of Sun Ra from David Brame’s “Dusty Funk Series,” and on the right is an illustration by Black Kirby member John Jennings.

This collection is always growing. Please search Watsonline, our online catalog, for additional titles, and be sure to check the Index of African American Artists to search for specific artists.