How can a physical space be designed to support well-being? While museum galleries might seem a world away from barbershops, to Joshua Livingston, both are places for people to gather and connect. Joshua is a visiting assistant professor in the American Studies Department at Bard College, and he’s spent many happy hours exploring The Met with his wife and young daughter, Jude. In 2020, he opened Friend of a Barber with his business partners. Made for more than haircuts, Josh’s barbershop is also a vibrant community hub that showcases work by local artists, and welcomes children and pets, too. Learn how for Joshua, spaces can be purpose-built to support meaningful connections that impact the whole community.

Subscribe to Frame of Mind wherever you listen to podcasts:

Listen on Apple Podcasts Listen on Spotify Listen on Google Podcasts Listen on Stitcher

Listen to the podcast

Transcript

Joshua Livingston:

That feeling as a barber to have someone come in and say like, “I trust you.” That’s the sweet spot, when someone comes in and says like, “Oh you know what to do,” because you gained their trust. That’s huge. Huge.

The barbershop is in every ballroom space. What do people resonate with? Do we need to rework something physically in this space? Do we need to change our operating hours? Because place is about the people. Whose history is represented and how is it displayed and how are people taking pride in that display?

Barron B. Bass:

Welcome to Frame of Mind, a podcast with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, about how art connects with wellness in our everyday lives. What does it mean for a community to come together and make space? It’s a question that Josh Livingston asks himself all the time. Josh is a barber and visiting assistant professor in the American Studies Department at Bard College.

Academically, he focuses on place-making and the design of community forums of business in the black community, and he draws from his own local barbershop to help inform that work. Putting art on the walls of his barbershop is just one of the many ways he tries to promote wellbeing in his community. Josh sees the sense of making space in his family life, too.

On the weekends, you may find him, his wife Natalie, and their six–year–old daughter, Jude, taking on the 5,000 years of art in The Met, one gallery at a time. To him, casual community spaces, like his barbershop or a stroll through The Met with his family, can be just as enriching as any grad school classroom.

Joshua Livingston:

The first time I cut hair I was 16. Barbering is like a rites of passage kind of deal. Like there are schools and stuff and the people just say one day like, “Hey I want to do hair,” but you know, a lot of people get this stuff passed down to them. My brother, who unfortunately during COVID passed away, but he was a barber and he taught me. And he didn’t teach me outright because I was like, “Hey I want to be a barber. So teach me how to cut hair.”

He taught me because he would cut my hair and he would let me watch. So the first time, you know, I wanted to grow my hair out a little bit and I wanted to cut my hair and my brother wasn’t around to cut it, I tried to cut my own hair. And I, there’s a term in the barber world called “zeeked.” It means, like you did a terrible job. Like I messed myself up and I was like, I was in tears. I didn’t go to school the next day. And then I had to fix it, and then I had to get better!

And then I started cutting my friends’ [hair] sometimes, it allowed me to gain some skill set enough to have the courage to be able to go and get a license. My brother, it is a way of honoring him and carrying the torch.

Before the pandemic, I was working as a barber and just was not sure I would ever even do a barbershop cause it takes a huge amount of confidence and faith that things will work out. I was feeling like I didn’t have the resources available to me to make it work. And I said to my wife, Natalie, “I don’t think I’m ever going to open a shop, like I don’t, I just don’t think it’s going to be in the cards for me to have a business.”

And then the pandemic came and Natalie said, “Josh, your clients in the city really really love you and I know that you love them.” And she just said like, “Why don’t you just try to find a place and get a chair and just sit and cut those people whenever we can go back and touch people again.”

And I was like, “That’s a great idea.” I called one of the guys who I work with, who is now a business partner and I say, “Hey man, I think when we go back, I’m just going to try to get a chair and do my thing.” And he was like, “You know what? I was thinking the same exact thing.” It was crazy but we were on the same page. It’s like, “Why don’t we build this thing and we can make it unique?” And it was born from that.

The owners of the shop are Greg Dasaro. Greg’s been cutting hair for about 15 years. And then there’s Mark Miguez—also been cutting hair for like 15 years.

Joshua Livingston:

The name of the shop is Friend of a Barber. The whole thing was built because of the love that we wanted to show because people showed love to us. And we want them to know that when you step in the door, this space was built for you. I’d always held the idea that community spaces, like barbershops, cafés, and those types of places are naturally occurring “academic” spaces. They don’t hold the same level of pretension that academia does.

Image of Friend of a Barber in the East Village. Courtesy of Joshua Livingston

Image of Friend of a Barber in the East Village. Courtesy of Joshua Livingston

Sometimes those spaces are locked, you know, you don’t get a chance to go inside them unless you have a particular GPA in high school or whatever. But there are a lot of people who have expertise from lived experiences. I find that there’s never a contrast or conflict with me being inside the shop. It’s always, how can I learn how to be better in our shop as a laboratory for knowledge acquisition, and how can I take from the barbershop and bring into the classroom? There’s a lot out here that we can learn from people who are just living their everyday lives going to get a haircut.

When people come together as a community to make place, there’s like a vibe in the air that people catch onto—but that vibe is intentional. People make that. When I think about place, I think about the Black community. And because I work with people in the development of physical space and how that makes you feel, and I draw upon so many elements within the architectural world and within the visual arts, that to me requires an artistic approach.

Aesthetics catch the eye of people and [there are] certain things that make people joyful. Like we chose Mountain Peak White paint from Benjamin Moore, instead of just any old white paint or super white paint. Like we knew the color we wanted to choose because Mountain Peak has an element of softness to the white and when your eye sees it, you feel it. It’s not just looking at it, you feel it.

Image of the interior of Friend of a Barber in the East Village. Courtesy of Joshua Livingston

Image of the interior of Friend of a Barber in the East Village. Courtesy of Joshua Livingston

Joshua Livingston:

So the walls are white, so that we can have lots of art. And this is Mark’s idea and I got to give him full credit for this. He said, when we were building this, he said, “What are the ways that we can engage our community around us, and our friends, and all of those other folks?” And he was like, “Well, what better way than to utilize the space that we have to give people a platform than to have them hang their art on the wall? What better place to have conversations about stuff like that than in a barbershop?”

And we think we did a pretty good job because people are buying stuff. And people are really having conversations. And they’re really enjoying the art. And people stay, like they’ll finish their haircut and l’ll be like, “Yo man, I got another client, like you gotta stop looking at the art.” Cause like, they’re walking around this space like it’s a gallery.

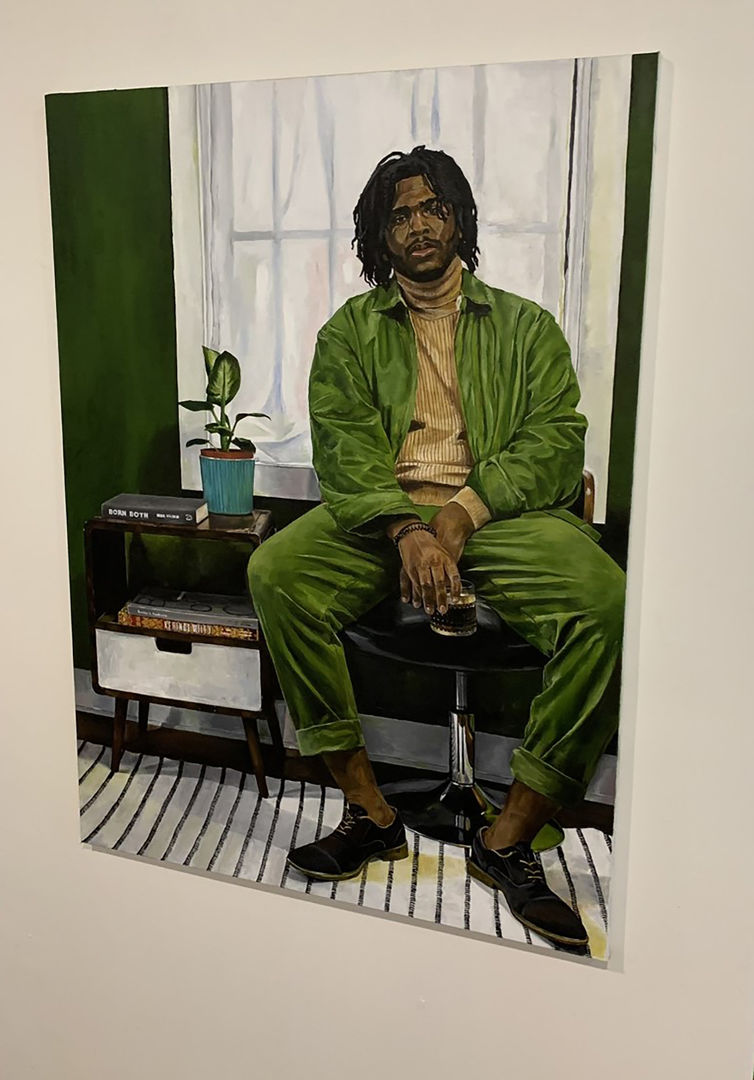

Image of Whiskey & Coke (2020–21) by Antonio Scott Nichols on Friend of a Barber’s walls. Courtesy of Joshua Livingston

Image of Whiskey & Coke (2020–21) by Antonio Scott Nichols on Friend of a Barber’s walls. Courtesy of Joshua Livingston

My daughter Jude is six years old. I think she likes to just be in that space and I think that it’s a special place for her.

Jude (kid):

Well, I like about it that daddy has, that daddy has a little bench for me to sit on.

Joshua Livingston:

What do you do at the barbershop when you come?

Jude (kid):

I wash towels, fold towels, and I help my dad.

Joshua Livingston:

And what about the floor?

Jude (kid):

And I sweep! And then we have ice cream fudge.

Joshua Livingston:

That’s right. You’re a great help at the barbershop. That’s your place. Like, the best part to me is that she doesn’t come in and tiptoe around and she’s not nervous. She just comes in says “Hey!” to everybody and she speaks to the clients.

Jude (kid):

My person, I mean dog, his name is Marty and I love hanging out with him. I have to feed him. I have to give him water. Oh, and I have to play with him.

Joshua Livingston:

Marty’s our shop dog, right? That’s Greg’s dog—my business partner, Greg, has his dog come by every day.

Jude (kid):

And Greg is Marty’s mom and dad.

Joshua Livingston:

I think that she knows it’s hers, just like it’s all of ours. It’s about community and it’s supposed to be about community in its purest form. I think museums are supposed to be about that, too. First thing we did when we came back to the city during the pandemic, we moved back into the Heights and we bought a membership to The Met because we knew that that would be a place that we can go, that we felt safe to go inside of.

This was the first, the very first time we went. Jude, I mean she loved it. She had the big wow moment. We make it a fun thing to walk in and say, “Look how grand this place is and all this artwork is for us.” But as a dad now, when you go into this, to The Met it’s like you’re, I’m constantly teaching. And then she’s teaching me how to teach her better.

Now, it means like, I need to do a little bit more research about where I want to take her inside the space, which then makes me more knowledgeable about what’s happening inside of The Met and what is in there, what exhibits are currently on display. It helps me to see things differently.

Her questions are from a child, like children ask amazing questions. They ask super blunt questions that you aren’t ready for, also. So they get you on your toes. But she’ll ask questions about the pieces. You’re not overanalyzing. You get a chance to take a step back. I think kids do that in general in life, especially in a museum.

In the past, you had to have, you know, a certain level of je ne sais quoi to be able to pull up to The Met. But, you know, they got this big institution like The Met and it could be overwhelming but for what I’ve done, thinking about place, is I’ve segmented it. So when I bring my family in, we try to take it a piece at a time.

Jude (kid):

First of all, daddy likes the armor stuff. And second of all, my mama likes that woman with a black dress in the painting—Madame X. And then I like the calming water in the Temple of Dendur. It’s a big room with water, you can throw coins in it and make wishes. And there’s this tiny stone of a crocodile. And then there’s all different kinds of statues. And, there’s this big big big…

Joshua Livingston:

What is it?

Jude (kid):

It’s so big and there’s so many mummies.

Joshua Livingston:

Is this, is this a large room?

Jude (kid):

And there’s one big mummy!

The Temple of Dendur, completed by 10 B.C. Egypt. Aeolian sandstone, Temple proper: H. 21 ft (6 m); W. 21 ft (6 m) ; L. 41ft (13 m). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Given to the United States by Egypt in 1965 and awarded to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1967 (68.154)

The Temple of Dendur, completed by 10 B.C. Egypt. Aeolian sandstone, Temple proper: H. 21 ft (6 m); W. 21 ft (6 m) ; L. 41ft (13 m). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Given to the United States by Egypt in 1965 and awarded to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1967 (68.154)

Joshua Livingston:

This is obviously just my opinion, but The Met’s responsibility is to continue to do the work it’s doing, and then some. It’s got to be out there telling people, like this Museum is for you. Same thing with the barbershop. When we built that place, we literally talked about people whose hair we cut and what they like and how they feel.

If you use those things the right way when you build place, you’re really sort of building, you’re building in social responsibility. You know, there’s ways in which to do social enterprise in that way. And what I mean by social enterprise is, and I want to define this correctly, social enterprise is not just businesses who care and want to give back.

Give back could mean take first. Sometimes just give. Let the community form, shape, mold this space together, collectively, and that it feels a certain way and that we hold each other accountable. They’re feel good kinds of places.

And I think everybody needs a barber, or a hair person. Like everybody needs, not just that it needs to be me, but you need somebody like that. People are fortunately and unfortunately tied to what they look like. Self-esteem is critically important. To have a high level of self-esteem is going to give you the courage and the confidence to be able to achieve whatever is in front of you and that you’re trying to achieve.

A really good friend of mine, I tell you his race because it was really important, it was hilarious —Black man and he said, “Yo last time you gave me a cut, like that was the one.” I was like, “Why?” I was like, “I’m glad but why?” And he was like, “Yo this older white woman came up to me on the street and crossed the street and she was like, ‘Yo that’s a nice haircut.” And he was like, “How does she know? Like how does she even know that my cut’s supposed to look like that?” And he’s like, “So like whatever you doing bro, you got like older white women in the street like hollerin’ at me.”

It was hilarious but it was a good point of wellness, right? It’s like yo, people really want to feel good about themselves. People want that recognition but they also want to know they got their armor on. Like, I can face the day.

I’ve had people tell me that when they come in to the space, it’s their second therapy of the week. Cause they’ll go to like a traditional therapist, and or, you know, a psychologist, or a social worker and then they’ll come to me. Friends that are clients, they know that when I talk to them, it’s my therapy. Cause they’ll come in and say like, “Hey, how’s it going?” And I’ll just like unload on them. So, it’s not just a one-way street, like I’m getting an opportunity to let out, you know, I need to let out. The shop has remained the place that makes me feel like I can really reflect and be safe.

Jude (kid):

I only let my dad cut my hair once and now, I’m never going to cut it, anymore, because I want it to be as long as Rapunzel.

Joshua Livingston:

So, it wasn’t a bad haircut, it’s just that she wants it to grow.

Jude (kid):

And my hair will reach all the way to Pennsylvania, Mexico, and Egypt. Everywhere! All around the world. Everywhere I go, it will drag.

Barron B. Bass:

Thank you for listening. This has been Frame of Mind, an art and wellness podcast from The Met. To find out more about Josh and the artworks mentioned in this episode, please visit the Met’s website at www.metmuseum.org/frameofmind where you’ll find bonus features, resources, and videos on the endless connection between art and wellness.

Frame of Mind is produced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Goat Rodeo. At The Met: Head of Content Sofie Andersen, Executive Producer Nina Diamond, Associate Producer Bryan Martin, and Production Coordinators Harrison Furey and Lela Jenkins. At Goat Rodeo: Rebecca Seidel is Lead Producer. Megan Nadolski is Executive Producer. Production Assistance from Char Dreyer, Isabelle Kerby-McGowan, Cara Shillenn, and Max Johnston.

Senior producer is Ian Enright. Story Editing from Morgan Springer. Series Illustration by Sophie Schultz. I’m your host Barron B. Bass. A special thanks to our guest on this episode, Josh Livingston. This podcast is made possible by Bloomberg Philanthropies and Dasha Zhukova Niarchos. If you liked this episode, please leave us a rating or review and share it with your friends.

Next time on Frame of Mind...

Margaret Golden:

Looking at art, reading about art, thinking about art calms me down. It’s one of the things I do when I find myself getting tense. I go into a different zone and the pandemic and other horrific things in the world outside aren’t there right then.

Supported by

and Dasha Zhukova Niarchos.