In the opening moments of The 24 Hour a Day Life of Benny Andrews (1974), the interviewer asks Andrews if he feels that he, as an artist, has made it. Andrews has something larger in mind than individual success:

In a case like ours, and I keep going back to “ours” because there are a lot of unanswered questions for us as Black artists - and of course this is in the context of, really, us as Black people in this country… If I get a little publicity or make a sale or two, that is not really necessarily a plus in terms of what I visualize as my aim in becoming an artist, in becoming what you call a successful artist. I’m trying to find a way to involve more people from the community and to involve myself more in the community. So, when you say, “making it,” I’m looking for that bigger thing.

Filmed in New York in the spring and summer of 1972, 24 Hour a Day Life documents Andrews’s pursuit of that “bigger thing,” and his intersecting roles as artist, activist, and educator.[1]

Andrews had arrived in the city fourteen years earlier to pursue his painting career. He was born in Plainview, Georgia, on November 13, 1930. After briefly attending college and serving in the Air Force, Andrews studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he developed the themes that would become hallmarks of his practice: a dedication to painting people and a material process that combined oil painting and collage. He moved to New York in 1958 shortly after earning his BFA.

Over the next decade, Andrews worked at a prolific pace, exploring themes of autobiography, race, and power. His paintings often focused on the lives of real or imagined Black subjects, such as laboring farmers in his 1965 “Autobiographical Series” or the solemn figure that towers over a Bosch-like landscape of white revelers in Shadow Over the Land (1966). By the late 1960s, Andrews was working with thick sculpted layers of collage and paint to construct overtly political images, including the satirical archetypes of Mr. America (1967) and The Cop (1968), and the wearily resigned countenances in Witness (1968) and No More Games (1970).

Benny Andrews (American, 1930–2006). No More Games, 1970. Oil on canvas with cut-and-pasted primed and raw canvas, T-shirt, garment fragments, and partially painted printed fabrics, overall 100 7/8 x 101 ¼ in. (256.2 x 257.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund (35.1971.a-b). © Estate of Benny Andrews / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

1968 was a pivotal year for Andrews as an artist, activist, and educator. His participation in New Voices: 15 New York Artists, a group show of Black artists, was an experience he later described as a turning point for finding a community of Black artists. That year marked the beginning of Andrews teaching in the SEEK Program at Queens College and his political activism to publicly protest the lack of Black artists in New York City museums.[2]

The SEEK Program served a primarily Black and Puerto Rican student body from New York’s poorest areas. Being a student of color on an overwhelmingly white campus would have resonated with Andrews’s experience in Chicago, and he later wrote that he joined the faculty because, “I’d be dealing with people I recognized and understood.”[3] 24 Hour a Day Life captures Andrews’s work in the classroom and his empathy for his students. He continued to teach there for nearly three decades.

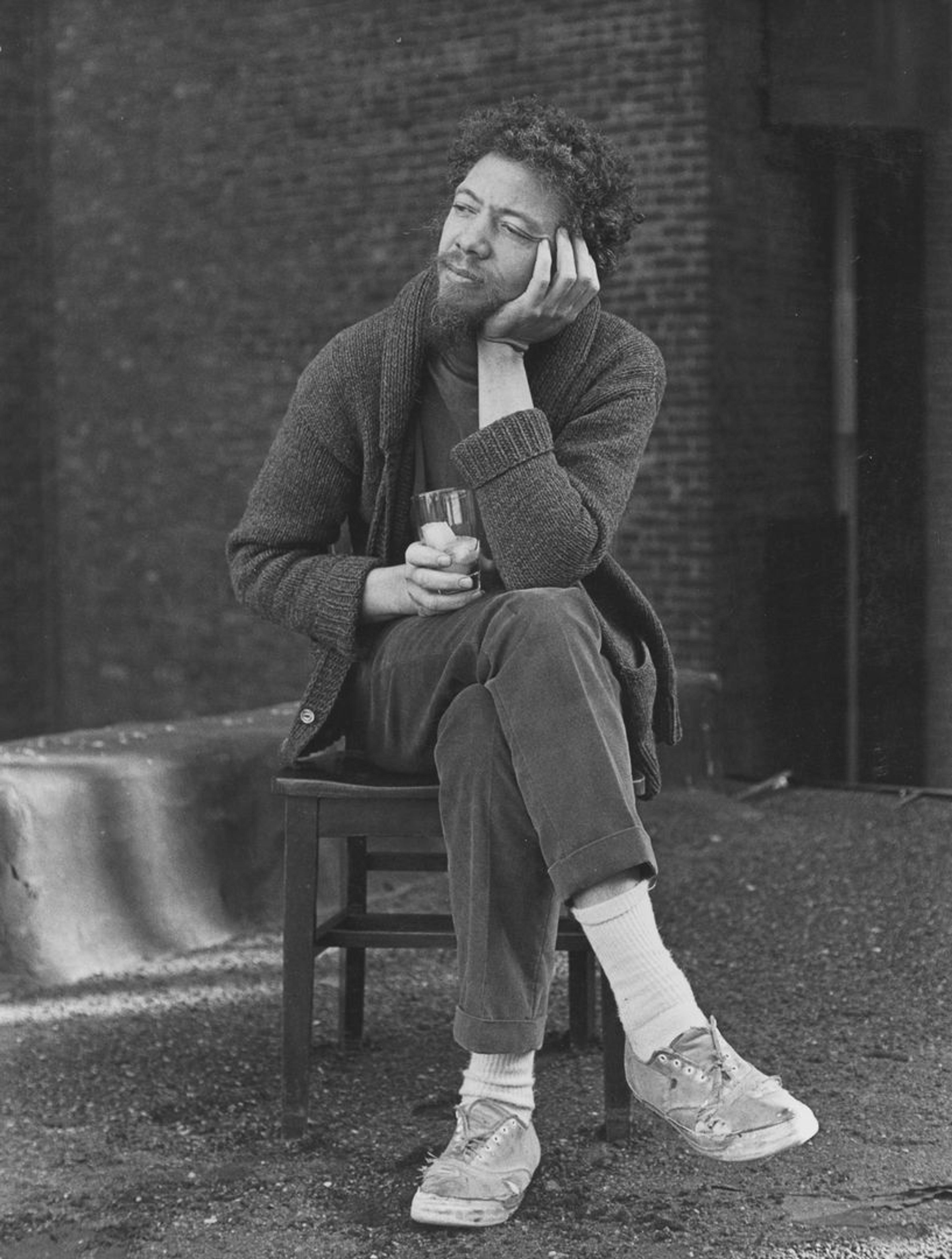

Benny Andrews in the late 1960s. Photographer and date unknown, possibly Dinah (“Dena”) Rubenstein (1910–87)

In November 1968, just weeks after he began at Queens College, Andrews joined artist Faith Ringgold, curator Henri Ghent, and others to protest the Whitney Museum over the complete absence of Black artists in its eighty-person survey of 1930s American art. That same month, Andrews joined other Black artists and leaders of the Harlem Cultural Council to publicly withdraw support from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s upcoming exhibition, Harlem on My Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968. This deeply flawed exhibition would become emblematic of the way Black artists and Black perspectives were excluded or ignored in American art museums.

Despite The Met’s role as a preeminent space for exhibiting and communicating the significance of works of art, curators planned to spotlight the culture of Harlem through an immersive installation of oversized documentary photographs and audio recordings rather than an exhibition of artworks that could represent the contributions of Harlem’s painters and sculptors. Frustrated by this exclusion and the fruitless negotiations meant to address it, Andrews and a group of artists including Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Ghent and others formed the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) and mounted an extended public protest of the exhibition’s January 1969 opening.[4]

Left: Benny Andrews (American, 1930–2006). The Cop, 1968. Oil on canvas with fabric collage, 24 x 18 in. (61 x 45.7 cm). McNay Art Museum, museum purchase with the Helen and Everett H. Jones Purchase Fund (2017.60). © Estate of Benny Andrews / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY. Right: Benny Andrews (American, 1930–2006). Witness, 1968. Oil on canvas with painted fabric collage, 48 x 48 in. (121.9 x 121.9 cm). Hood Museum of Art, purchased through gifts by exchange from Evelyn A. and William B. Jaffe, Class of 1964; Kent M. Klineman, Class of 1954; and Mr. and Mrs. Joseph H. Hazen. © Estate of Benny Andrews / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

Andrews and the BECC continued their push for greater representation. Over the next two years, the group negotiated with the Whitney Museum’s leadership, demanding they show more Black artists and hire Black curators. Although the Whitney ultimately agreed to dedicate a space for solo exhibitions of Black artists and to mount a survey, Contemporary Black Artists in America (1971), the BECC boycotted the exhibition, arguing that the museum had not lived up to its commitments to hire or consult Black experts and curators.[5]

By the 1972 filming of 24 Hour a Day Life, the BECC had turned its focus to its Prison Arts Program, which Andrews established the previous fall with support from the Junior Council of the Museum of Modern Art. The documentary follows Andrews, his BECC co-chair Cliff Joseph, and a small group of teaching artists leading a class in the Manhattan Detention Center, known as “The Tombs.” The all-volunteer Prison Arts Program would remain the central project of the BECC throughout the 1970s, eventually expanding to a national level.

Benny Andrews (American, 1930–2006). Trash, 1971. Oil and mixed media collage on canvas, 120 x 336 in. (304.8 x 853.4 cm). The Studio Museum in Harlem, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley Katz (1981.14.1a-l). © Estate of Benny Andrews / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

As Andrews’s commitments to activism and education deepened, he embarked on an ambitious years-long series of monumental paintings, “The Bicentennial Series.” The first of these works, Symbols (1971), was eight by thirty-six feet and was central to Andrews’s first solo museum show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The second, Trash (1971), was originally presented at the ACA Gallery exhibition documented in 24 Hour a Day Life, though the ten-by-twenty-four-foot work is captured only briefly as Andrews loads it in sections into a van. Andrews intended these sprawling allegorical works as a response to what he knew would be the omission of Black history and Black voices in the national Bicentennial celebration.

24 Hour a Day Life concludes with its narrator reflecting, “Involvement, undying commitment, and programmic [sic] focus were the characteristics that give credence to the legacy of Benny Andrews.” The description is apt, but incomplete. Andrews grounded his life in an art practice powered by experimentation and imagination, and one in which he was committed to the freedom of making; of telling any story he wanted to tell. “We are entitled to have representations of people that look like us and talk and feel like us,” he remarks in the film. Andrews’s larger project was to make space for that artistic commitment—for himself, his students, his peers, and his community.

Notes

[1] Benny Andrews, “Journal of Benny Andrews: From December 20, 1965 till November 4, 1972.” April 15 and 22; May 24 and 27; June 14; July 11; September 25; October 7, 1972. Andrews-Humphrey Family Foundation, Brooklyn, NY. Andrews’s journal documents his first meeting with John Wise on April 15, 1972. Wise filmed Andrews bringing artwork to ACA Gallery on April 22, and Andrews’s Queens College classes and ACA exhibition opening on April 25. On May 24, Wise traveled with Andrews to Washington, D.C., to film the protest in which Andrews participated. Wise and his crew filmed Andrews’s studio on May 27 and at the Manhattan Detention Center on June 14.

[2] Andrews, “The War Years,” manuscript dated December 12, 1973. Andrews-Humphrey Family Foundation. 1–5, 22–24.

[3] Ibid, 24.

[4] Susan Cahan, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). See chapter two for a description of the planning, execution, and subsequent protests of the exhibition Harlem on My Mind.

[5] Ibid, see chapter three, as well as Howard Singerman’s essay “Rebuttal and Representation,” in the exhibition catalogue Acts of Art and Rebuttal in 1971, edited by Singerman and Sarah Watson (New York: Hunter College Art Galleries, 2018). See Singerman’s essay for a description of the BECC’s boycott and counter-exhibition to the Whitney’s Contemporary Black Artists in America. This counter-exhibition was at Acts of Art, a gallery Andrews discusses in 24 Hour a Day Life.