Today, the American painter Alice Neel (1900–1984) is known for her incisive “pictures of people.” Born and educated in Pennsylvania, she spent a year in Cuba before settling in New York City in 1927, where she painted obsessively, capturing the spirit of the city and the life of its citizenry.

In 1978, the filmmakers Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes completed an ambitious project, a film triptych entitled They Are Their Own Gifts about three women artists: Alice Neel, the poet Muriel Rukeyser, and the choreographer Anna Sokolow. We spoke with Murphy and Rhodes about their portrait of Neel via email.

Alice Neel: They Are Their Own Gifts (1978)

Do you remember your first encounter with Alice Neel’s work?

Lucille Rhodes:

Margaret Murphy and I discovered Alice while researching to apply for a film grant from the New York State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. It was just after the end of the Vietnam War and at the height of the 1970s Feminist movement. Margaret and I were both engulfed in the intensity of this distressing and exciting period.

Margaret Murphy:

My first encounter with Alice and her work was when Lucille and I started making the film. I was working as a film editor in the Olympics unit for ABC Sports. Alice said to me, “You look sporty!” Clearly she was very perceptive. I didn’t realize that one of us would be the subject of a new work.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Ninth Avenue El, 1935. Oil on canvas, 24 × 30 in. (61 × 76.2 cm). Cheim and Read, New York © The Estate of Alice Neel

Rhodes:

We were interested in making a film on three mature, critically acclaimed women artists whose lifelong commitment to social justice was reflected in their work. What comes to mind is a reproduction of Alice’s painting Ninth Avenue El. It’s a very sad picture of the heaviness and gloom of the Depression. It depicts lost souls roaming the streets. Alice’s genius in portraying the life and faces of past eras was exactly what Margaret and I were searching for. Alice Neel, Muriel Rukeyser, and Anna Sokolow agreed to work with us.

One of the most extraordinary aspects of this documentary is the intimate look it provides of Neel in her studio. What was it like to work with her?

Rhodes:

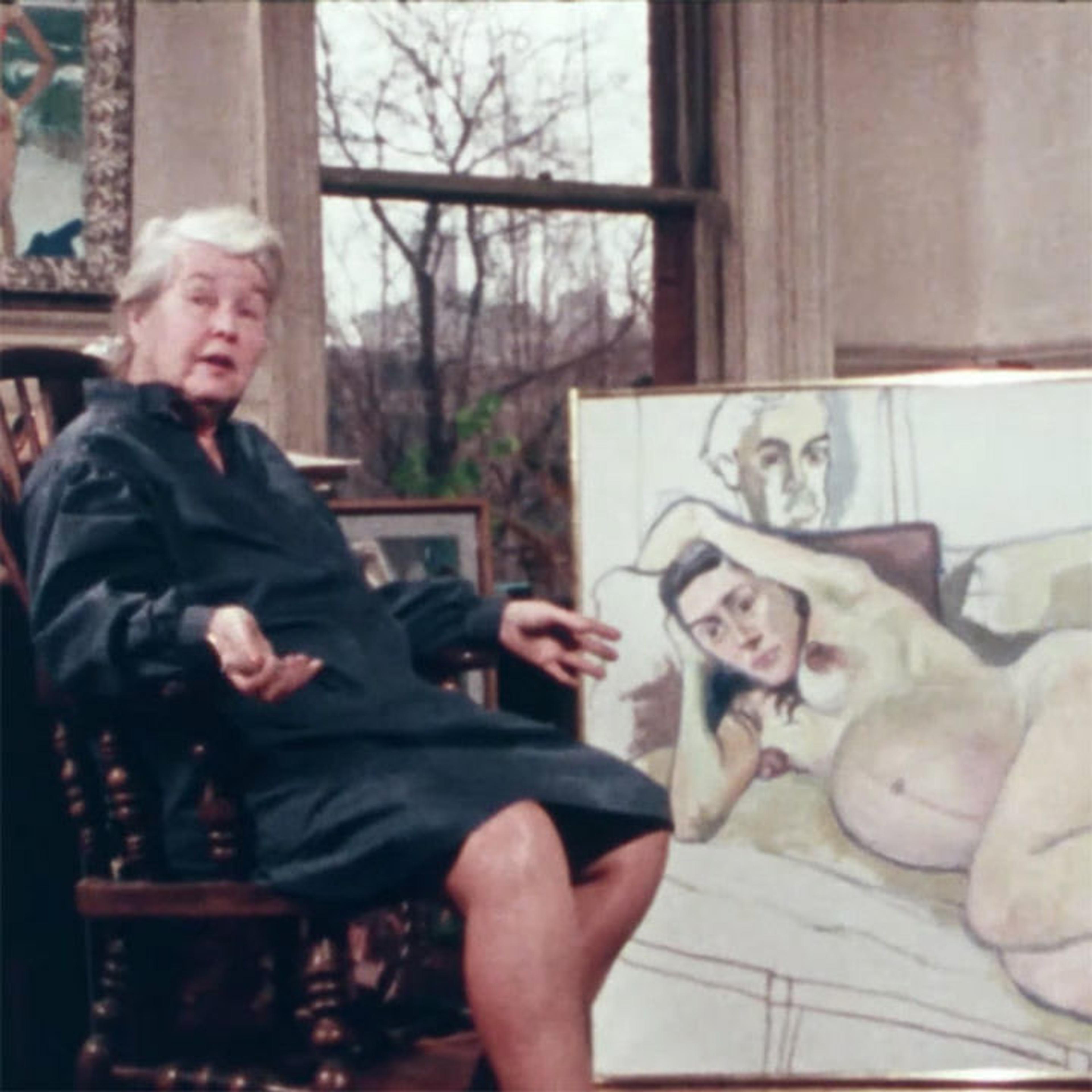

Alice was charming, ingenuous, tough, funny, mercurial, and very mischievous. At first she was leery of us, and there were long pauses in our conversations when she stared silently at our faces. Then Margaret noticed that she was staring more at me, and soon after Alice asked me if I tweezed my eyebrows. After several film sessions, we requested that Alice allow us to film her while painting. She declined. A few days later, she said she would let us film her working if I would pose for her.

“One of the reasons I painted was to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle.”

— Alice Neel, “They Are Their Own Gifts” (1978)

Murphy:

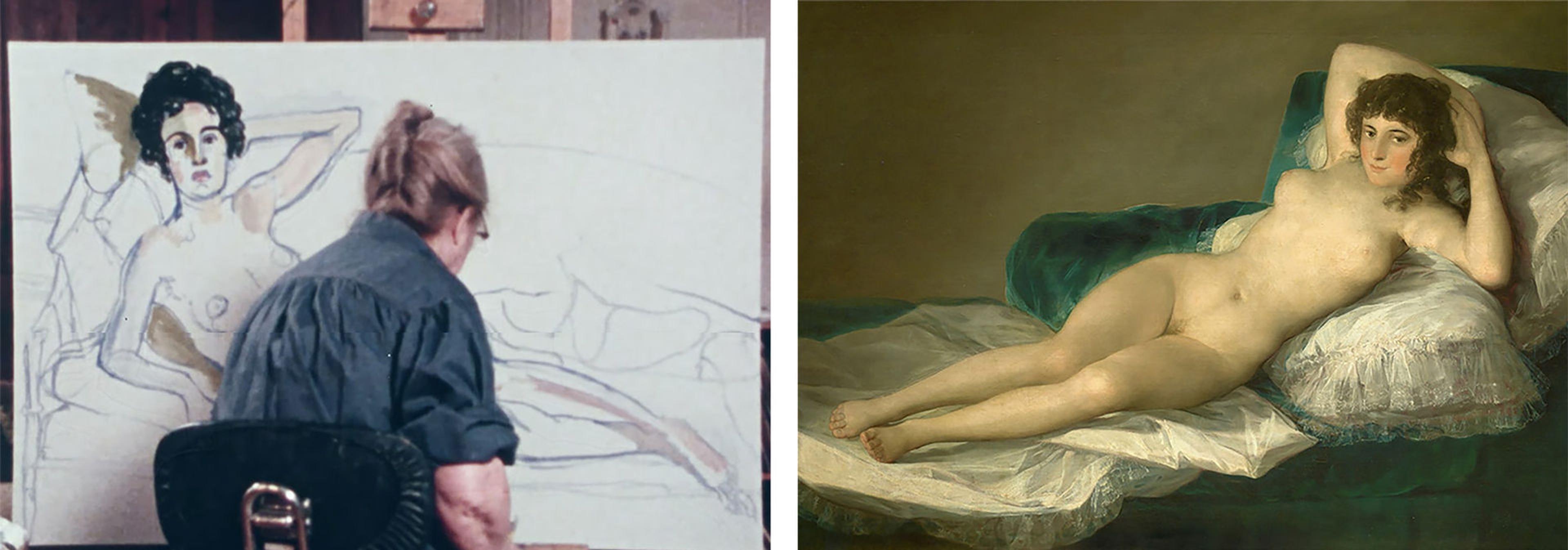

We wanted to capture her in the process of painting, so Alice suggested she paint Lucille in the nude. I was taken aback, but Lucille was a good sport and agreed. We may have had a notion that it was Alice’s way of controlling her story as well as her art. It went well, and it is a beautiful painting. Alice was a natural on camera, very much in her element, chatting with her subject as she reminisced.

Rhodes:

I was now in the same vulnerable position as the film’s subject. From then on, she was very relaxed, focused, and open during our many sittings and I, as an art history major, was flattered to assume the position of Goya’s The Naked Maja. Babette Mangolte (Chantal Akerman’s cinematographer) and Margaret were the only crew in the room. It was January, and I reclined near a leaky window, freezing.

A few years later after we finished the film, Alice was asked to participate in a group show at Long Island University. Although she was aware that I was the chairman of the theater, film, and dance department, she decided to send the portrait of me, entitled Lucille Rhodes. I got a call from my flustered dean, who had already shipped it back to Alice. That’s pretty mischievous!

Left: Still from They Are Their Own Gifts (1978). Right: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746–1828). The Naked Maja (detail), 1795–1800. Oil on canvas, 97.3 × 190.6 cm. © Museo Nacional del Prado

Murphy:

Alice, at the age of 76, lived in an old building on the Upper West Side. She once had to be rescued from the elevator when it broke down. Her apartment was her home, her studio, and her storage space for the hundreds of paintings that had not yet been sold or acquired by a museum or gallery. She painted in her living room. During one break for a snack we shot her in the kitchen, where she had drawn images on the wall. She was surrounded by her art. She made many of her paintings available for us to shoot, and we placed them around her so that she could refer to them in an immediate and intimate way.

Alice was a real trouper over the many days we spent with her. A great storyteller with a good sense of humor. My favorite line in the film is, “I was a very good-looking girl so my whole life was disrupted by men.” Alice told her own story through her work. We had no additional interviews. It was just Alice and occasionally Lucille’s voice off camera.

How long did it take to make this film?

Murphy:

We were constantly leap-frogging from subject to subject and from editing room to editing room over a three-year period. We were lucky to have Lucille’s red VW bug to take our boxes of film from place to place. And film back then was a very labor-intensive medium. Our budget evaporated quickly, but we did manage to complete the project.

Rhodes:

Margaret said it took us three years, but it felt like ten years. Our original concept was to interweave the three subjects, but after endless editing we were still not satisfied. We asked the brilliant film director and editor Charlotte Zwerin (Gimme Shelter, Salesman) to take a look at the hour-long work and she urged us to make a triptych. So we started all over again, working on weekends and nights, schlepping huge metal cans from one editing room to another for another year. We named the film They Are Their Own Gifts, taken from a poem by Muriel Rukeyser. It premiered as one film consisting of three twenty-minute portraits.

Neel painted in obscurity for years. While many of her contemporaries’ reputations have ebbed, hers only seems to grow. Why do you think her work has struck such a chord today?

Murphy:

I believe the awareness of Alice Neel has grown because her work remains relevant. Her portraits of labor leaders, civil rights activists, industrialists, and political figures are a visual record that touches on many chapters of our history. She was “a collector of souls,” as she said, and her collection encompassed distinguished artists as well as the poor who were her neighbors.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Lucile Rhodes, 1976. Oil on canvas, 40 x 60 1/8 in. (101.6 x 152.7 cm). © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy the Estate of Alice Neel and Victoria Miro

Alice had a distinctive style that reached the essence of her subject, but it was also very direct. Alice was plainspoken and her work seemed to be an extension of her no-nonsense character. The more time we spent with her, the more we appreciated her talent and skill. She said, simply, “Well, if you don’t keep getting better at what you do then you’re in the wrong profession or there’s something wrong with you.”

Rhodes:

In the film, Alice quotes a critic who called her “the woman who paints like a man.” I suppose he meant that her depictions are direct, grand, and unapologetic. She considered this remark “anti-women.” The art world, at the time we interviewed Alice, was overwhelmingly male. Also, portraiture, as well as other forms of figurative painting, were denigrated.

In the last few years, museums and galleries have been reevaluating the work of women artists and their contributions to the history of art. Alice’s body of work is clearly outstanding. I believe that her innovations, particularly in the last twenty years of her life, revitalized the genre of portraiture.

Did you feel any tension between Neel’s painted portraits and the image of Neel in your film—the expressionism of her work in contrast to the “hard objectivity” of the camera lens?

Murphy:

I do feel there is a parallel between the obsessive effort Alice put into her work and the labor it takes to create a film. It can be exhausting and frustrating but fun and satisfying as well. If you have the opportunity and you're good at it, it's a good curse to have.

Rhodes:

Neel’s eye and mind extended way beyond the camera’s potential. She had a razor-sharp surgical intuition that located her subjects in their era both historically and psychologically. I would say that her portraits were more incisive and often crueler than our edited portrayal of Alice. However, she was kind to my image. She softened her view of me as a harsh, intense feminist by bathing my figure with the colors of mother-of-pearl, as if I lay in a shell. She saw me inside and out.

This interview has been edited for publication.

The film, They Are Their Own Gifts, is distributed by Women Make Movies.