This article in the From the Vaults series takes a deeper look at Robert J. Flaherty's silent film The Pottery Maker (1926), and concludes with an interview with silent-film accompanist Ben Model, who composed and performed an original score that premiered last week.

The Pottery Maker, 1926

Robert J. Flaherty (1884–1951), often credited as the father of documentary film, is most famous for Nanook of the North (1922), Moana (1926), and Man of Aran (1934). While in New York awaiting the release of Moana, his second feature, Flaherty made a remarkable short film for The Met, The Pottery Maker: An American Episode of the XIX Century. Some consider it a "hidden key" to his oeuvre.

The narrative is simple enough: a grandmother and granddaughter visit the local pottery to purchase a new pitcher, but the curious youngster has plans of her own. For a filmmaker like Flaherty—famous for his epic depictions of man versus nature, often in extreme circumstances—the sweet, quiet storyline is perhaps surprising. He was known to shoot footage of whatever he deemed interesting until the budget ran out, and only then started the process of editing.

Nearly one hundred years after the fact, much about this film's production remains unclear, given slender primary evidence. Was it produced in 1925, as many sources claim, or in 1926? Was it filmed in the Museum's basement or off-site at the Greenwich House Pottery in Greenwich Village? There are adamant partisans on either side, and theories abound.

Perhaps most strangely, it's still disputed whether Flaherty was truly the film's director, or if it was the stage actress Maude Adams. Some have suggested that Adams was the film's sponsor, and we can assume that she provided the experimental lighting system, which she was working on at the General Electric Laboratories in Schenectady, New York.

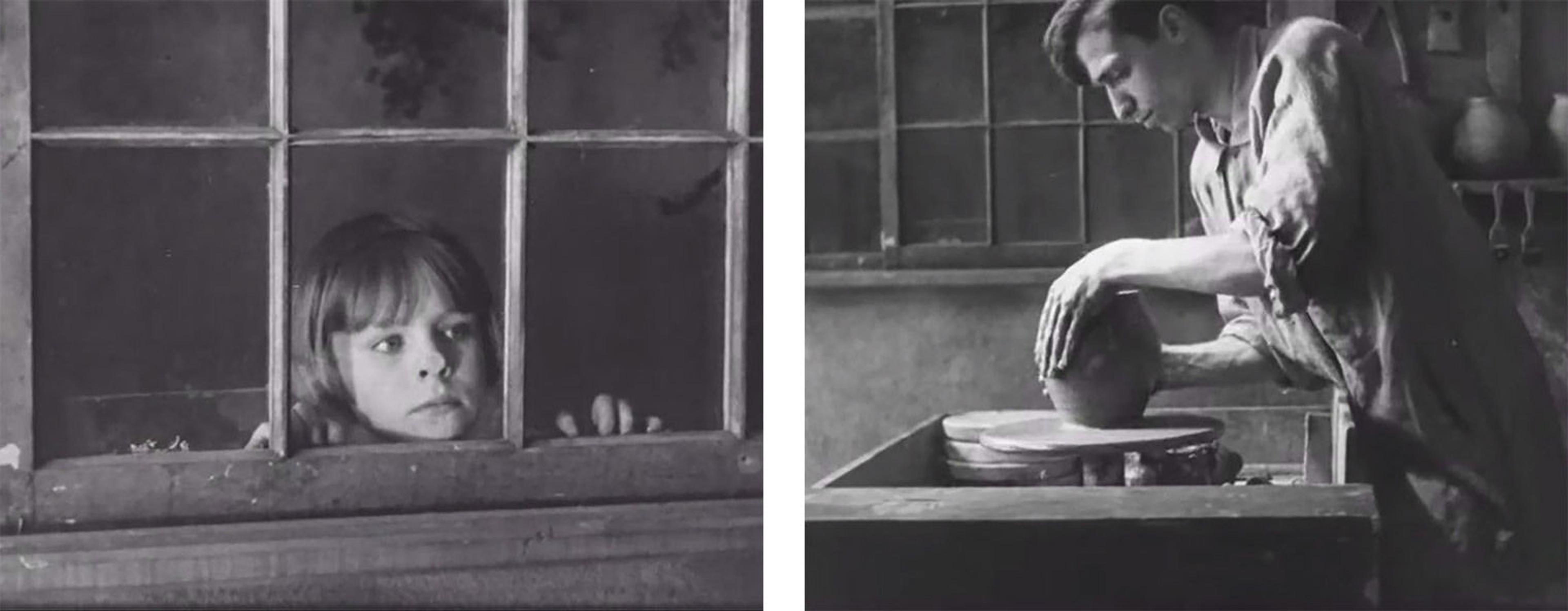

Stills from The Pottery Maker, 1926

While some facts remain hazy, we've managed to clarify that the film was completed between the end of May and September 1926. We've learned that the leading man was Victor Raffo, the first student at Greenwich House Pottery and a long-time faculty member there. The young girl is Raffo's daughter, Ruth, and it's well documented that the grandmother was played by Elizabeth "Libbie" Bacon Custer, widow of General George Custer. (She has been described as a "patron of the arts.") Greenwich House provided some of the equipment; additional costumes and pottery may or may not have come from The Met's American Wing.

Despite the lingering questions, the film has retained its allure over the years. Perhaps most notable is the filmmaker's particular attention to the potter's concentration and skill as he works the clay on the wheel. The careful cinematic observation of a skilled hunter, dancer, or fisherman at the height of his craft is certainly a constant in all of Flaherty's films; years later, he would include a sequence of a potter at the wheel in Industrial Britain (1931). The lighting of The Pottery Maker—as well as the composition of its shots, and the somewhat off-kilter framing—is noticeably more assured and more accomplished than the other Met films of the period.

We're pleased to present this mysterious little gem of the early cinema for your viewing pleasure. We hope you enjoy it as much as we do, and that perhaps you'll learn a bit about the ancient craft of pottery along the way. This film is part of From the Vaults, our year-long series of selections from The Met's extensive moving-image archive.

Before COVID-19, we had planned an in-house screening of silent films in Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium with live piano accompaniment by Ben Model, known to many for his performances at the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. Given the precarious situation, however, the realization of this dream seems increasingly unlikely.

We're honored that Model scored The Pottery Maker in lieu of a live performance. For those eager to hear more, stay tuned: later this summer, we plan to release a new score for a short feature on the American painter Childe Hassam. Below, please enjoy a short interview with Model, which has been edited and condensed for publication.

Ben Model at Loew's Jersey Theatre. Photo © Steve Friedman, 2014, courtesy Ben Model

How did you start as a silent-film piano accompanist? What was your first gig?

I started accompanying silent films when I was a film production major at NYU. This was just before the era of VHS, laserdisc, and DVD, and all the films were shown in 16 mm. The available silent 16-mm films had no scores, so the films were presented every week in dead silence. I'd been a silent-film fan and had taken piano lessons since I was a kid, so I offered to accompany the film screenings. I started off playing for the basic film-history course taught by Robert Sklar, and then played for courses taught by William K. Everson.

I made a point of meeting, hearing, and speaking with the people who were playing for silents in New York City to learn about film accompaniment. I met and talked with William Perry at MoMA and with Lee Erwin at the Carnegie Hall Cinema. Lee had been a movie organist in the 1920s and became a mentor and friend to me. I absorbed as much as I could from him.

How does your relationship change to the films as you score them—your perception of movement and gesture, facial expressions, etc.?

My relationship with the films in general improves and gets enhanced year after year by my own interest in understanding the directors' work, style, and viewpoint, and from going on the journey of the film with the audience. As a silent-film accompanist, you develop a sixth sense where—out of the corner of your brain—you become aware of the vibe in the room, and so part of the scoring is helping the audience in the cinema fuse their imaginations up and into the world of the film. I've also learned a lot about the rhythms and the making of silent comedy films, as well as an appreciation for them, by participating (when I can) in the NYC Physical Comedy Lab.

Do you incorporate popular songs of the period? Do you use elements of pastiche or quotations when you score a silent film?

No, I don't. It's distracting and it calls attention to the accompanist. This was actually a somewhat common practice in the silent-film era, most probably borrowed from vaudeville or stage melodrama. The practice of "corny" "olde tyme" piano music and song-title puns got used in spoofs of silent films going back to the 1930s and it's been repeated over enough decades that everyone thinks that this is what silent-film scoring is supposed to be. The device has a different meaning to audiences today; using a tune familiar to everyone sends the signal "don't take this seriously." This was one of Lee's big bugaboos, and I think because I came to film accompaniment as someone who was also a filmmaker it resonated with me.

The exception, of course, is when there's a scene in a film where someone sits down at a piano, we are shown the sheet music, and the character plays and sings that song in the scene.This can be tricky: some well-worn classical music has been reworked into pop tunes over the years. In The Mysterious Lady (1928), Greta Garbo and Conrad Nagel fall in love through a performance of Puccini's Tosca and "Vissi d'arte" from act two is played on the piano a few times as "their song." Well, Elvis Presley's "I Can't Stop Falling in Love With You" uses that melody. You want to honor the original scene but also know the audience is going to think, "Why is he playing that Elvis tune?" during a love scene.

How does this tradition survive? How does it get passed onto future generations? Institutional backing? Education?

In the last few years, a few musical conservatories have had programs where students create new ensemble and orchestral scores for silent films. But mostly, every once in a while, someone in their twenties or thirties (or younger) just gets the bug for it. Most people, I find, figure out how to accompany silent films on their own. It's very rare that someone asks for advice or instruction the way I did when I started. This past spring semester, though, a student at Wesleyan University—where I teach a course on silent-film history—approached me about learning to accompany silent films, and I'm thrilled about that.

How does this tradition relate to the history of music generally?

Silent-film accompaniment has a preservation element to it, in terms of the actual performance. Unlike most music, it's created and performed in service of presenting another medium: pre-1930s cinema. Music, in general, evolves year by year and decade by decade, whereas silent film is static and rooted in a specific time.

What were your favorite parts of scoring The Pottery Maker? And the short profile of Childe Hassam?

The Pottery Maker has something of a realist quality to it, even though it's been made as an educational narrative. Part of scoring the film was the challenge of supporting performances by the two non-actors—the little girl and the potter—and of the woman playing the grandmother. I enjoyed discovering that these 1920s films were made for a cultural-educational purpose by The Met. I knew that MoMA was instrumental in making motion pictures available in 16 mm to universities and museums in the 1930s. Finding out about The Met's adoption of motion pictures as a method to educate beyond the walls of the Museum was intriguing.

How have you adapted in the time of COVID-19? Are you performing via livestreams?

On March 16, I launched a weekly livestreamed silent-film series called "The Silent Comedy Watch Party." I co-host the show from my apartment, and pipe in my friend Steve Massa remotely from his place. We show three silent comedy shorts, which Steve introduces and which I then accompany live on my acoustic piano. We've gotten a lot of support and have attracted viewers from all over the planet. It's been great. We've heard that people are watching with their kids, discovering people like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. The die-hards are getting a kick out of revisiting some of the "warhorses" we run, as well as the obscure gems with comedians like Marcel Perez, Hank Mann, and Alice Howell.

How does that experience differ from performing for a live audience in the theater?

Well, I have to sense-memory conjure up that sixth-sense awareness of what the audience response would be like when I do these shows. Some of the films I know really well in terms of the audience response. Like, with Keaton's One Week (1920) or Chaplin's The Adventurer (1917). But for something like Sweet Daddy (1921) with Marcel Perez—where I don't have as many performances of it in my memory banks—I'm working more in a mode that's akin to when I record scores for DVD releases.

The one aspect that's really different, and that I'm still working on, is that I'm much more aware of the fact that I'm playing in someone's living room. It's that intimate, audience-of-one sensibility that's essential when you're an on-air radio host or correspondent. Because these are livestreams, I'm aware that there are hundreds of people watching at the same time I'm playing, but I have to remember not to play the piano like I'm trying to fill the space of a movie theater, but rather that my audience is several feet away or even less. My broadcasting hero is Ernie Kovacs, and I try to follow the way he comports himself to the camera and home audience.

It will be interesting to see what effect what I'm doing in these performances will have on my live shows, once the cinemas and museums and other venues resume screenings.