In the beginning, there was analog—and it was good.

The Met began to produce its own motion picture films in 1922, making it one of the first museums to embrace this new-fangled medium. As early as 1925, there were regularly scheduled film screenings for Museum members, with screenings open to all visitors starting the following year. As soon as there were Met films, there was a very active film-rental program for these productions. To ensure they would reach the widest audience possible, as early as 1928 The Met began reducing its 35-mm film prints to non-flammable 16-mm acetate, allowing for screenings with portable—and self-operable—projectors. And for shining moments in 1970 and again in 1977, The Met collaborated with the American Cinematheque to offer series of film screenings at the Museum.

When I started at The Met in November 1981 as the manager of the Junior Museum auditorium, I knew nothing of this history. I hadn't even been aware that there were movie projectionists—union members, like myself, licensed by the City of New York to run 35-mm motion-picture film—working at the Museum. On the first day, I was shown the projection booth and introduced to Ray Cusie, the artist and departmental technician who is the subject of "A Look at The Metropolitan Museum," released on From the Vaults this February. Ray and I were to share an "office"—really, it was a storeroom, piled floor to ceiling with audio-visual equipment. The room was painted a beautiful electric blue, because Ray had somehow managed to convince the higher-ups that the preposterous color provided the best environment for video quality control. As we sized each other up, I was handed a typewritten list of films owned by the Museum. And so the adventure began.

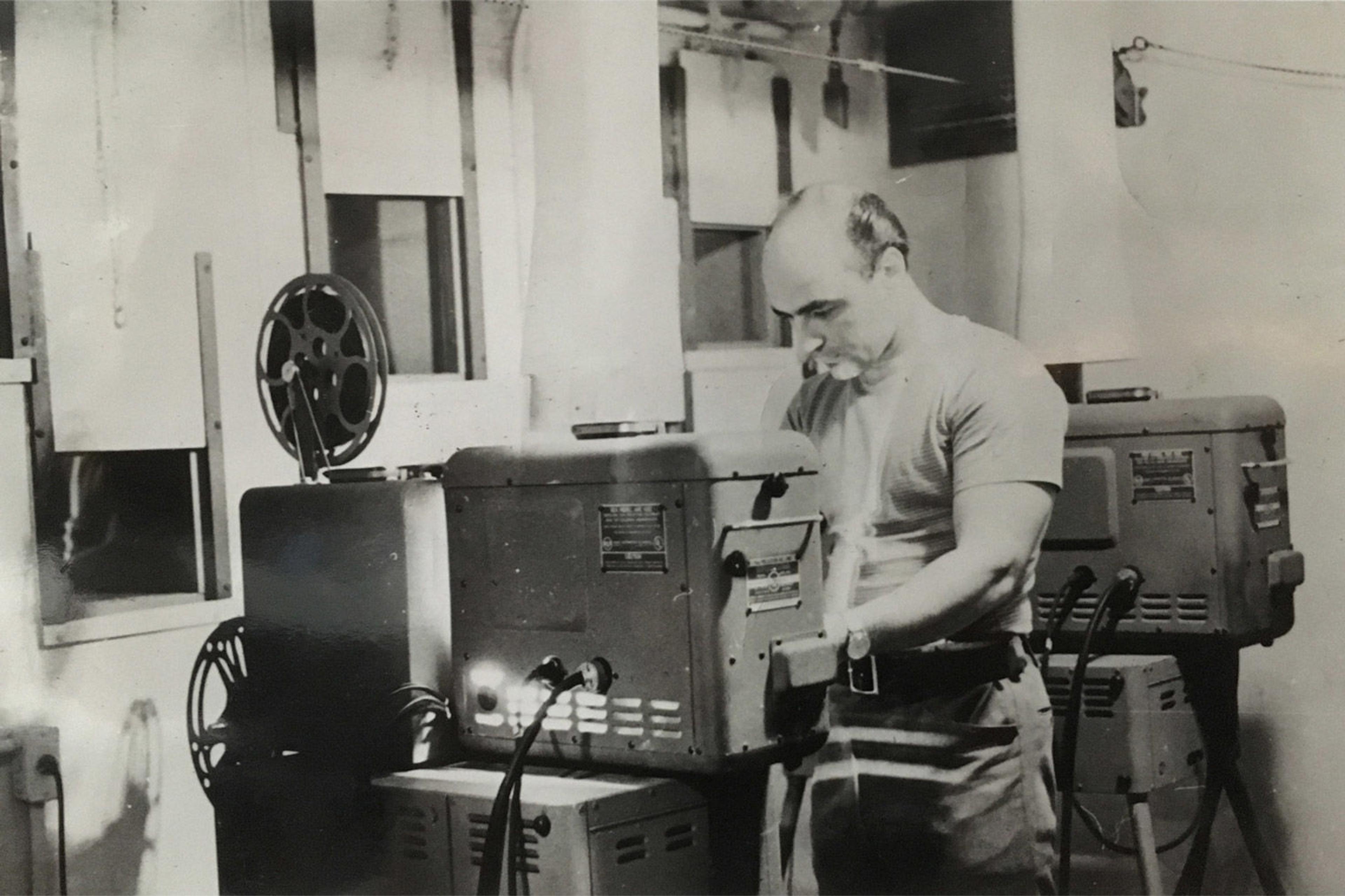

Ray Cusie trimming the carbon arc of an RCA Porto-Arc 400 16-mm projector, Junior Museum auditorium booth (ca. 1960s–early '70s).

It was an odd time to start working in the Junior Museum; it was in the process of closing, and reopened fifteen months later as the first iteration of the Ruth and Harold D. Uris Center for Education, accessible today by the 81st Street entrance. The auditorium was under renovation during that time, and there were few public programs to run on Saturdays, so I often wheeled a portable 16-mm film projector into the storeroom for film and video. (Cassettes had been introduced to the home market in 1977, but in 1981, films still greatly outnumbered videos on the storeroom's shelves.) The films and tapes shared a space with the Christmas tree when it wasn't on view. The room wasn't really climate-controlled, but at least it was air-conditioned—a big improvement over the previous film storerooms scattered around the building, including one down in the basement near the boilers.

I spent many happy hours on those slow Saturdays, familiarizing myself with the film collection. There were of course Met productions, as well as commercially produced films on artists and art history. In addition, the staff of the Junior Museum had for many years actively sought out films appropriate for family screenings. I especially enjoyed the animated films—classic titles from the National Film Board of Canada, as well as all kinds of quirky indie shorts. There were animations made with objects, collages, sand, clay, or pinscreens; drawn on cels, or painted directly on film. Among the films were excerpts from TV broadcasts, fillers from public television, "soundies," and Oscar-winning shorts—anything that could be used to illuminate art and art making, to educate while entertaining. During this time, I was fortunate to take a workshop at the Media Center for Children on the use of films to inspire creative activities. When the auditorium reopened in January 1983, I took up my projectionist duties again, but also began programming the family-film screenings. These ran on Saturdays throughout the year, with additional programs shown daily in the summer.

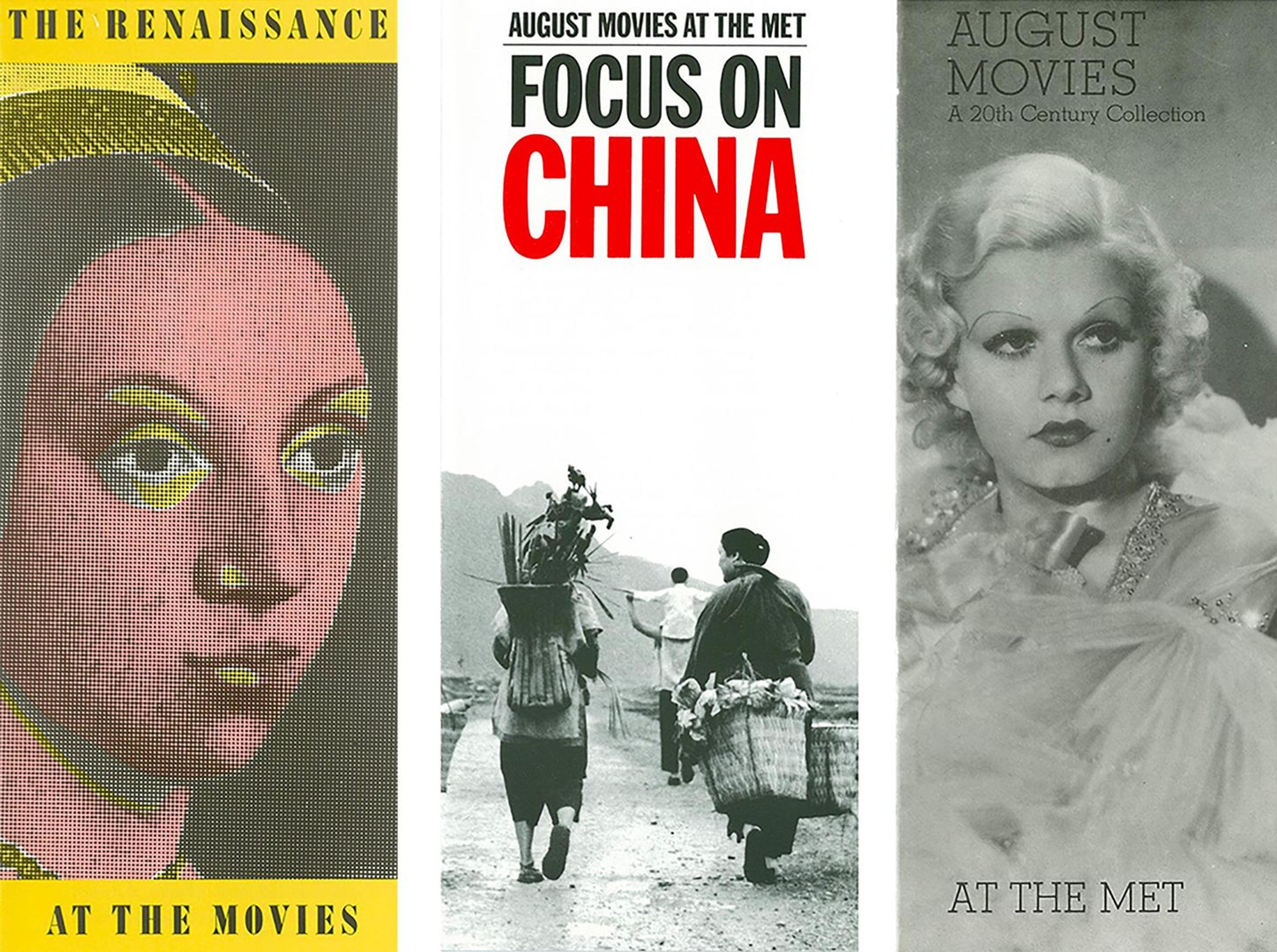

A selection of brochures advertising August film series at The Met: "The Renaissance" (1985), "Focus on China" (1988), and "A 20th Century Collection" (1987).

Perhaps I should note here that my mother disapproved of my being a mere projectionist. "Some career," as she put it. Never mind the fact that I was working at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The day she finally visited me in the projection booth, crowded with equipment, and saw for herself the 35-mm projectors with their carbon-arc lamphouses, she was gobsmacked. They were hulking, greasy beasts to her, but familiar beauties of industrial design to me. (She never complained about my job again.) Truthfully, I didn't run much 35-mm film at The Met, although one of the last features I ever projected in the Uris Auditorium, in December 2003, was on those beloved machines: a 35-mm print of Russian Ark (2002), which featured a cast of thousands and was shot in one continuous take in Saint Petersburg's Hermitage Museum—an astonishing feat of choreographed movement.

In time, the films, videos, and other media were granted a properly chilled storeroom of their own. These many legacy formats reflect decades of evolving technology and The Met's accumulation thereof. There are film cartridges, filmstrips, audio-cassette/slide sets, over a dozen varieties of video, optical discs, and more. The late seventies and early eighties had seen the introduction of Portapaks and other lightweight recording gear, making independent video production much easier. And The Met did make tentative forays into reel-to-reel video production, but only really embraced video once cassettes were in wide distribution. The eighties were an especially active time for film and video production on art-related subjects, both at the Museum and elsewhere. The Met's Office of Film and Television produced some two dozen documentaries while it was open from 1981 through 1994. At the same time, the Program for Art on Film, a joint venture between The Getty and The Met, produced collaborations between filmmakers and art historians. And the Museum's Department of Education also produced its own films, so there was a rich source of material for programming.

All of these productions, and many more, were part of popular screenings—sometimes they were way too popular. The occasional Saturday feature-film screening, particularly of period costume dramas, inevitably attracted an overflow crowd; the disappointed visitors who were turned away often did not leave quietly. Yet there were so many lovely encounters with visitors who were moved by and grateful for the experience. I would pop into the back of the theater to make sure the audio was okay and then linger to enjoy the audience enjoying the films. Knowing that I had made this communal experience possible was a very rich reward.

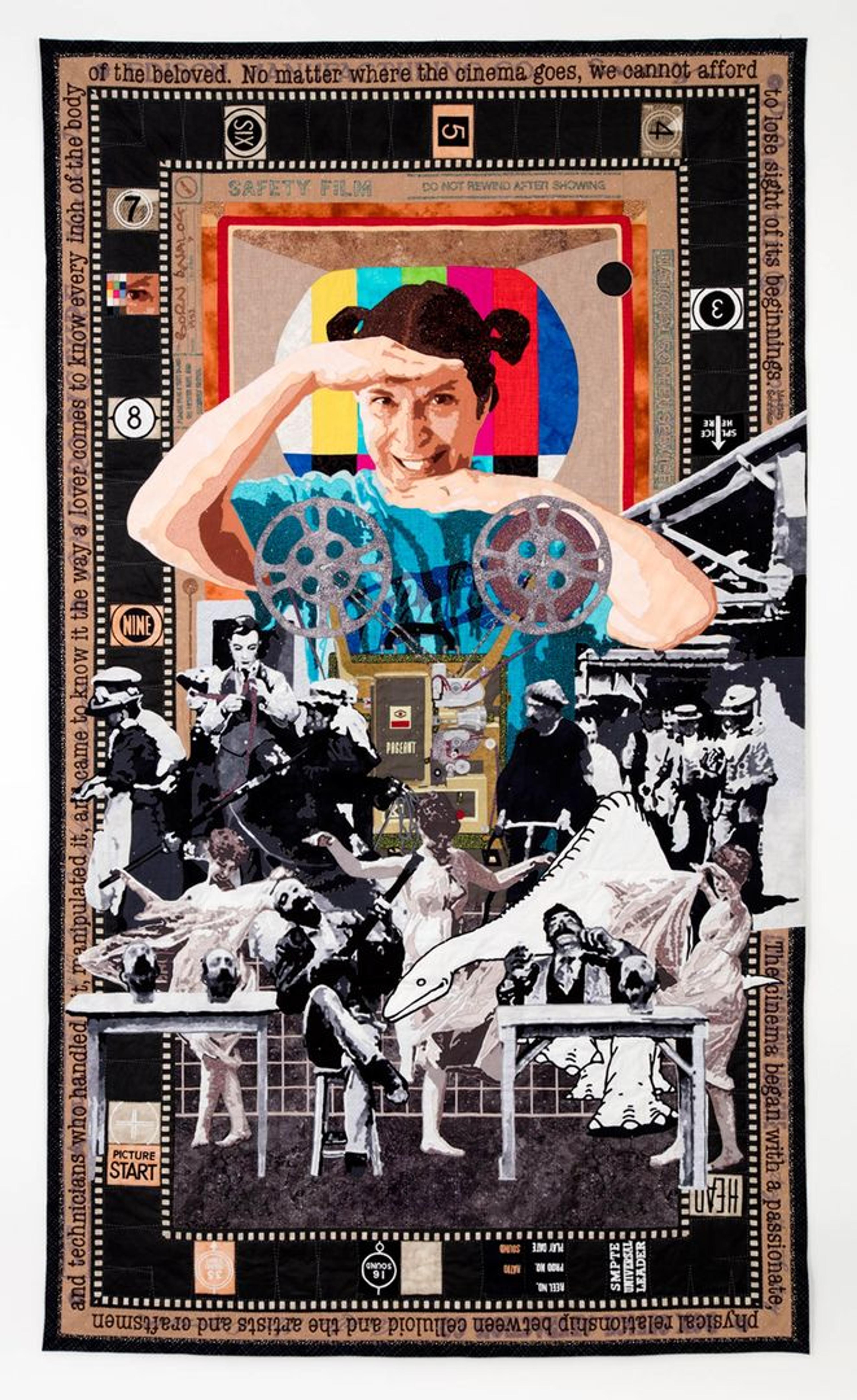

Left: The author in front of her work-in-progress Born Analog. Right: The author in The Met's current cold-storage facility (2020).

My little theater closed for good in January 2004 to be renovated out of existence. When the Uris Center reopened, there no longer was an auditorium. (The Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium, built in 1954, often shows films, but does not host regular series.) But The Met's film and video production never ceased, even without a brick-and-mortar screening venue; the media-production team moved to the newly formed Digital Department in 2009. The film program limped along for a time, but eventually even the weekly screenings ended. I understood that the most valuable, immediate experience of art was up in the galleries, rather than mediated through film. Nevertheless, the thought that all those wonderful films would languish on the shelves, unseen and unloved, was wrenching for me.

Fast-forward to the present, when all of you reading this now have the opportunity to discover or rediscover these films through our yearlong archival film series, From the Vaults. It's truly mind-boggling to think that anyone with a phone in their pocket can call up the whole history of cinema on that little screen. Will it be the same experience as sitting in a large, darkened room, among friends and strangers, with a film projector chattering away at the back? No, of course not. Yet even I, the most analog person who will ever work in a digital department, can marvel at how digitization is bringing old films to a far broader audience than could ever sit in an auditorium. I do urge you, gentle viewer, to slow down and allow yourself the time to appreciate these gifts from a different era, when multitasking hadn't yet taken over our lives.

I hope you will love these films as much as I do.

Robin Schwalb. Born Analog (2016). Silk-screened and commercially available cotton fabrics, thread; fused, machine appliquéd, hand appliquéd, machine pieced, hand quilted, 80 x 47 in. (203.2 x 119.4 cm). Photo courtesy Jean Vong / Quilt National. Work of art © Robin Schwalb

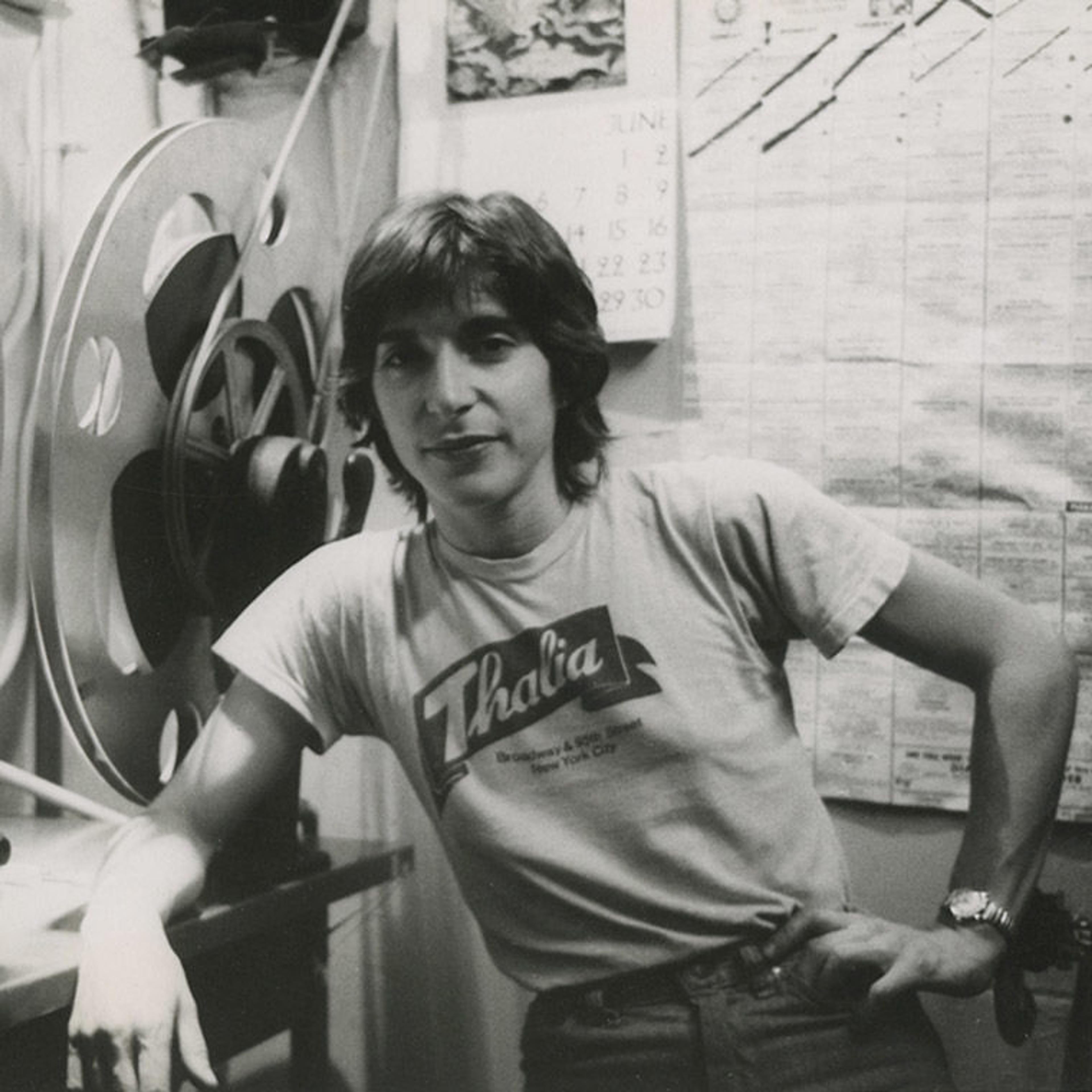

Marquee: The author, Robin Schwalb, at the rewinder in Thalia Theater, New York (1978).