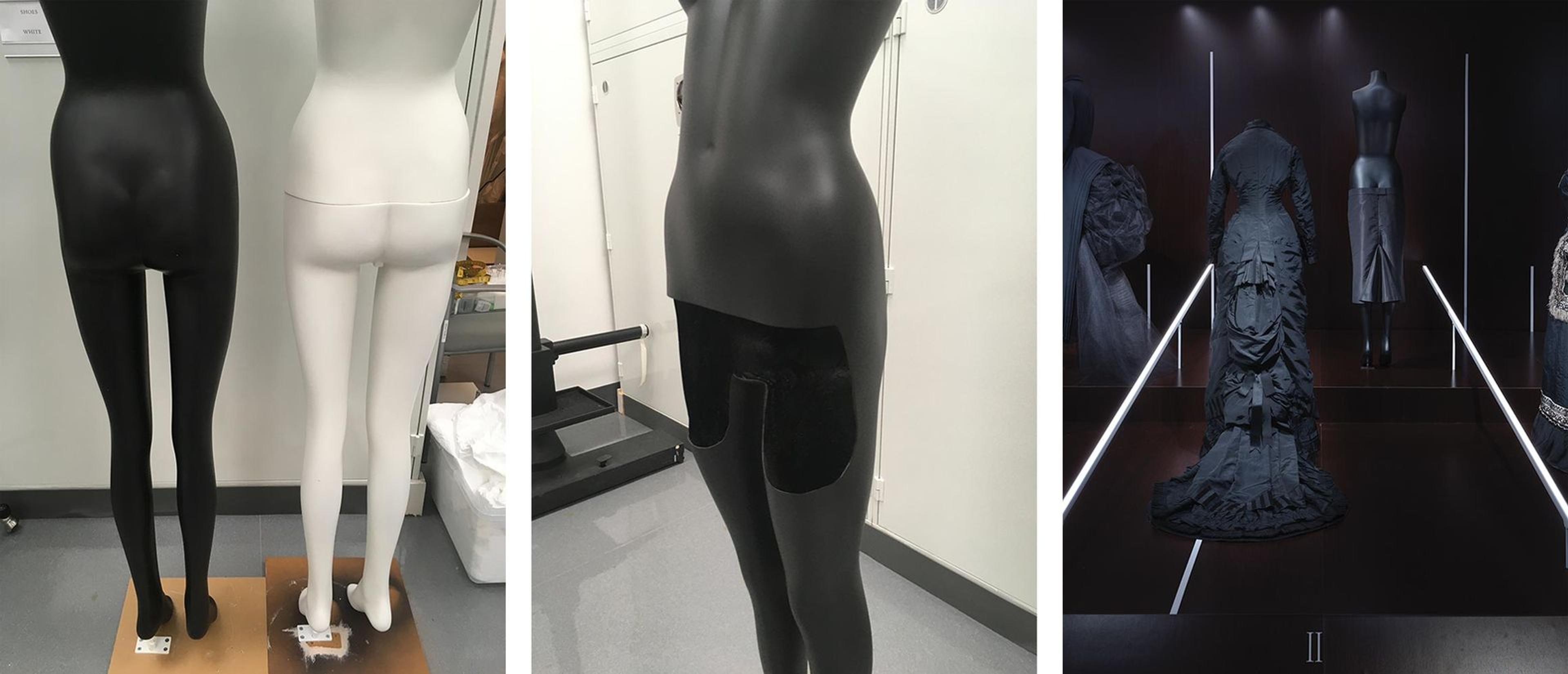

Left: Torsos returned from cutting and painting. All photos by the author unless indicated. Right: Installation view of About Time. Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

Virginia Woolf is the acknowledged ghost narrator in The Costume Institute’s exhibition About Time: Fashion and Duration. Unacknowledged are the other 124 apparitions in the clock face and the serpentine galleries of the exhibition. Their presence is suggested by clothing displayed in three-dimensions, as if worn on a body; but with nary a visage or limb in view, the clothing appears magically suspended on the platforms.

As Senior Research Associate in Installation at The Costume Institute, I am de facto dresser of mannequins for photography and exhibitions. Once or twice a year, when we put on our Spring or Fall exhibitions, the dressing work is carried out by an expanded team including members from the Curatorial, Conservation, and Collections areas of The Costume Institute, as well as contract dressers. In addition to preparing the costumes to the standards set by precedent and approval of the curators, I receive guidance and support from Conservation, especially in regards to fragile costumes or those of unusual materials.

Image: 18th-century panniers inspired this Rick Owens ensemble on the set used by the exhibition’s catalogue photographer Nicholas Alan Cope

Phase one of our work on About Time began when we photographed the objects for the exhibition catalogue last January. The art direction called for minimal background and minimal mannequins to contrast with the mostly black ensembles. The exhibition’s design proposed tracing the changing styles from the 1870s to the present in two intersecting timelines: one continuous and one disrupted, with the curation of black garments heightening the effect of gradual and sometimes rapid evolution of outlines and shapes, fullness and hemlines, emphasis and constrictions. The use of the white headless mannequins on a white seamless backdrop emphasized the costume’s silhouettes in the catalogue photographs. Using more than a dozen mannequins at our disposal, we photographed more than 120 ensembles during seventeen days of shooting.

Left: Marc Jacobs dress on a Schlappi mannequin for neckline and belly(!) trace. Center: Although the arm can be used with the final mount, the hand cannot, necessitating an extension, made of Ethafoam for the long sleeves. Right: The “hollow” belly as final dressed. Perry Ellis Sportswear Inc., designed by Marc Jacobs (American). Dress, spring/summer 1993. Rayon, Lycra. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Perry Ellis International, 1993 (1993.97)

Phase two began with prep for the exhibition itself, when we had more time to make customized mounts for each ensemble. A rotating team of twelve dressers worked for about fifteen weeks to make mounts and dress the forms for 125 costumes. Individualized attention was given to each invisible, or “ghost,” mount. With a surplus of old mannequins and limited time, we decided to make invisible mounts from existing mannequin bodies, rather than make the bodies from scratch. From our inventory, we chose the mannequins or dress forms whose fit and posture best suited each ensemble.

We dressed the mannequin in an ensemble and traced the neckline with a pencil to mark the area of the form to be cut away. Then, we undressed the form and put aside the costume. Sleeveless garments needed the armholes marked to be cut away, as well. We sent fiberglass forms to a mannequin repair shop for cutting and painting, while our Principal Departmental Technician Michael Downer cut the papier-mâché dress forms. The resulting shells of bodies allow the viewer to look through the neckline of the garments into the body cavity.

Papier-mâché mount for Norman Norell’s “mermaid” dress wrapped in black jersey

Traina-Norell, designed by Norman Norell (American, 1900–1972). Dress, ca. 1955. Silk, synthetic, metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Starr Haymes Kempin and Evan A. Haymes, in loving memory of their mother, Gail Lowe Maidman, 2017 (2017.316.7)

We painted the mounts black inside and out for a seamless look to match the black ensembles. We also draped some mounts with fabric in the interior to better match the costumes’ color and texture. We attached pole stands to dress forms and fiberglass forms to mimic the height achieved by mannequin legs. We then dressed the objects on the mounts in their final preparation, with their necessary padding and underpinnings.

Left and center: Buckram formed around mannequin legs to mimic shape. Right: Installation view of the Gaultier dress (left) in About Time. Jean Paul Gaultier (French, born 1952). Dress, fall/winter 1984– 85. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts, 2010 (2010.155a–c). Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

We gave particular consideration to ensembles of sheer or lace fabrics, with skinny or barely-there shoulder straps, as well as to trousers and period looks. For objects from the 1870s to 1900, we used special mannequins from the Kyoto Costume Institute, which are designed specifically for historic costumes from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; each era’s ideal body shape (on a human body, achieved through corsetry) is incorporated into the rigid mannequin.

Mount for Weeks dress with arm stubs covered in nylon stockings supporting net illusion sleeves. Weeks. Evening Dress, 1918–20. Silk, rhinestones, metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the estate of Mrs. Arthur F. Schermerhorn, 1957 (2009.300.3569)

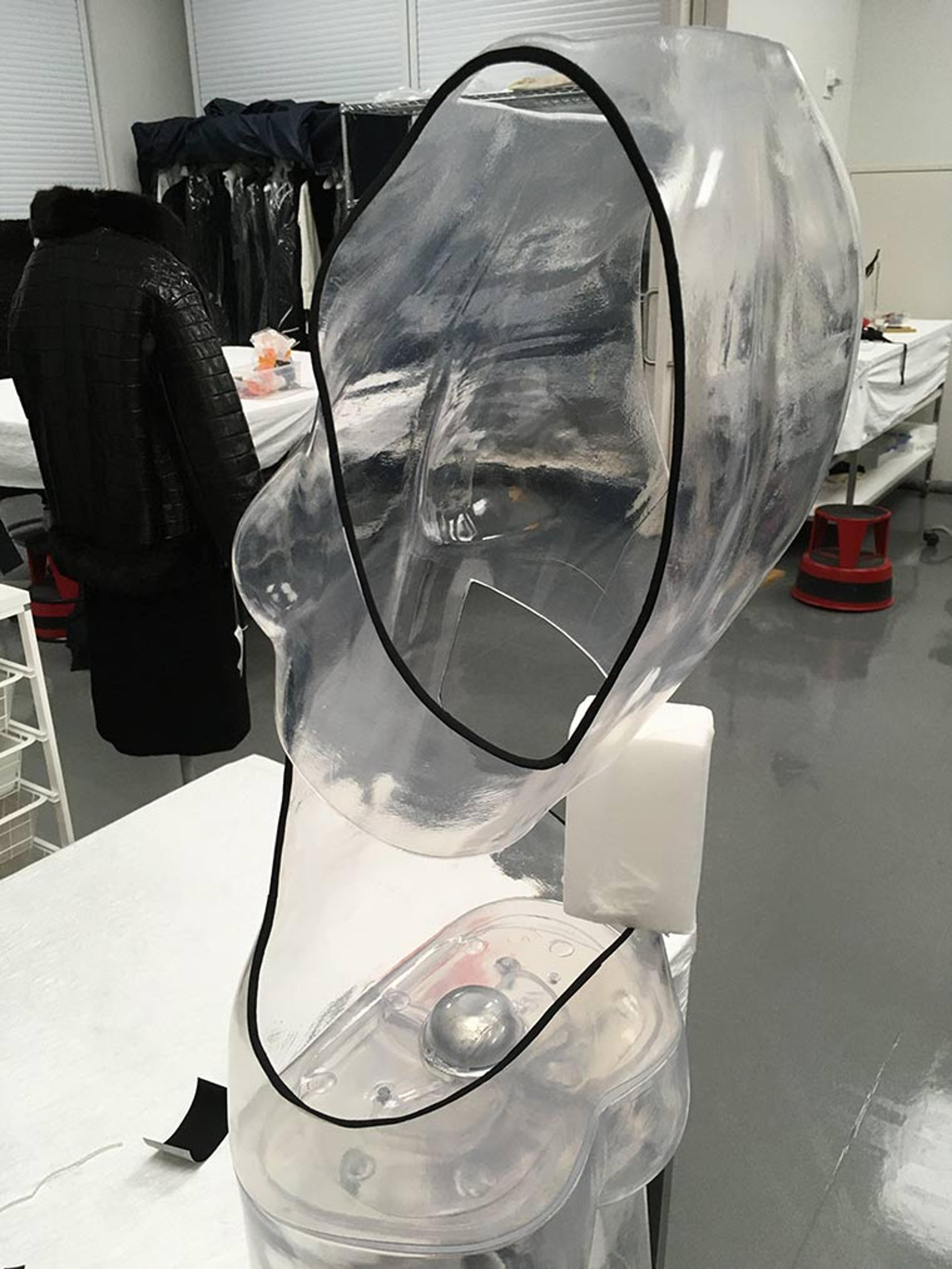

In some cases, buckram was formed around the mannequin to serve as the foundation of the invisible mount. To preserve the transparency of chiffon or lace, we used a clear mannequin made from high-impact polystyrene, which required extra finishing of the edges with black tape. For dresses and mannequins with lost shoulders, Conservator Glenn Petersen sewed the top edges of the dresses to the mounts to distribute the weight and keep strappy dresses from slipping down the body.

Clear mount for a Raf Simons for Jil Sander string dress with taped edges

Installation view of the Raf Simons for Jil Sander dress (left) in About Time. Jil Sander AG, designed by Raf Simons (Belgian), Dress, spring/summer 2009. Silk, synthetic. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Allison Sarofim Gift, 2010 (2010.3.1). Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

Gianni Versace metal mesh dress on clear torso for tracing. Gianni Versace (Italian, 1946–1997). Evening dress, fall/winter 1987–88. Metal, cotton, silk, glass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Gianni Versace, 1993 (1993.52.6)

Installation view of the Versace dress (right) in About Time. Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

One mount, featured in the first gallery, was not entirely an absent body. It required extra work to display a “bumster” skirt designed by Alexander McQueen, as we needed to reduce the circumference of the mannequin at hip level to fit the skirt. We enhanced the rear cleavage and permanently connected the seam normally seen between the separable mannequin torso and legs. The continuous look supported McQueen’s admiration of elongated torsos and lower backs, as reflected in its pairing with the modish princess-line dress from about 1877.

Left and center: Mannequin with enhanced backside and cutaway thighs for “bumster” skirt. Right: Installation view of the “bumster” skirt (right) in About Time. Alexander McQueen (British, 1969–2010). “Bumster” Skirt, fall/winter 1995–96, edition 2010. Courtesy of Alexander McQueen. Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

Dressing historic and contemporary ensembles requires care in handling and knowledge of fashion history and the body. Finesse in styling and attention to detail further enhance the presentation. Making the effort to engineer mannequins and mounts to highlight objects without distraction offers visitors to About Time a ghostly and magical experience.