As a child, I loved playing with paper dolls. They were not only beautiful, but for an immigrant child from a low-income family, they were also affordable. When I grew older and learned how to handle scissors, I started to make my own. A particular favorite was a paper carriage, led by a driver and two horses, carrying a prince and a princess whose faces could be seen through the cut-out windows. As an eight-year-old, I did not think about the symbolism of my paper dolls and their carriage, but as a toy scholar, I now realize that they participated in an intricate web of meanings. While the paper dolls served as outlets for my imagination and artistic creativity, they also inadvertently reflected very specific domestic and societal values. Even though they were made from simple materials, they promoted the ideal of conspicuous consumption, implying, for example, that a rich wardrobe would ensure happiness.

Left: Published by Selchow and Righter. Our Favorite Dolls: Paper Doll in Lacy Underdress, ca. 1900. Color lithography. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Doris V. Reinhard, 1941 41.114(1). Right (top): Published by Selchow and Righter. Our Favorite Dolls: Scottish Hat, ca. 1900. Color lithography, 2 3/4 × 5 3/8 in. (7 × 13.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Doris V. Reinhard, 1941 41.114(8). Right (bottom): Published by Selchow and Righter. Our Favorite Dolls: Scottish Dress, ca. 1900. Color lithography. 11 1/2 × 7 3/4 in. (29 × 19.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Doris V. Reinhard, 1941 41.114(2)

My paper dolls are part of a long lineage whose origins can be traced to around 105 CE in China, where they emerged soon after paper was invented.[1] These early paper figures were not playthings; they served as charms with important ritualistic functions.[2] For example, they were burned in funerals to purify the deceased. Around the seventh century CE, the custom of making paper figures migrated to Japan, where they also played important roles in religious ceremonies and were connected to sorcery. From Japan, papermaking (and with it, paper dolls) spread across Asia, reaching Arab Muslim centers such as Cairo, Mecca, and Baghdad by the eighth and ninth centuries, and Europe soon after through the Muslim conquest of Spain.[3] From Spain, where the first paper mill was established in 1151, papermaking began to spread across Europe, reaching France in 1189 and Germany in 1320.

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press further increased the demand for paper.[4] The first commercially published European paper doll was likely the French pantin, or clown puppet, invented around 1720. Pantin was widely used as a children’s toy but also served as a tool for political and social critique, satirizing figures such as the king, judges, aristocrats, and the clergy.[5]

Imagerie d'Epinal. Pierrot (Pantin), ca. 1865. Lithograph colored with pochoir. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirsten, 1969 (69.558.90)

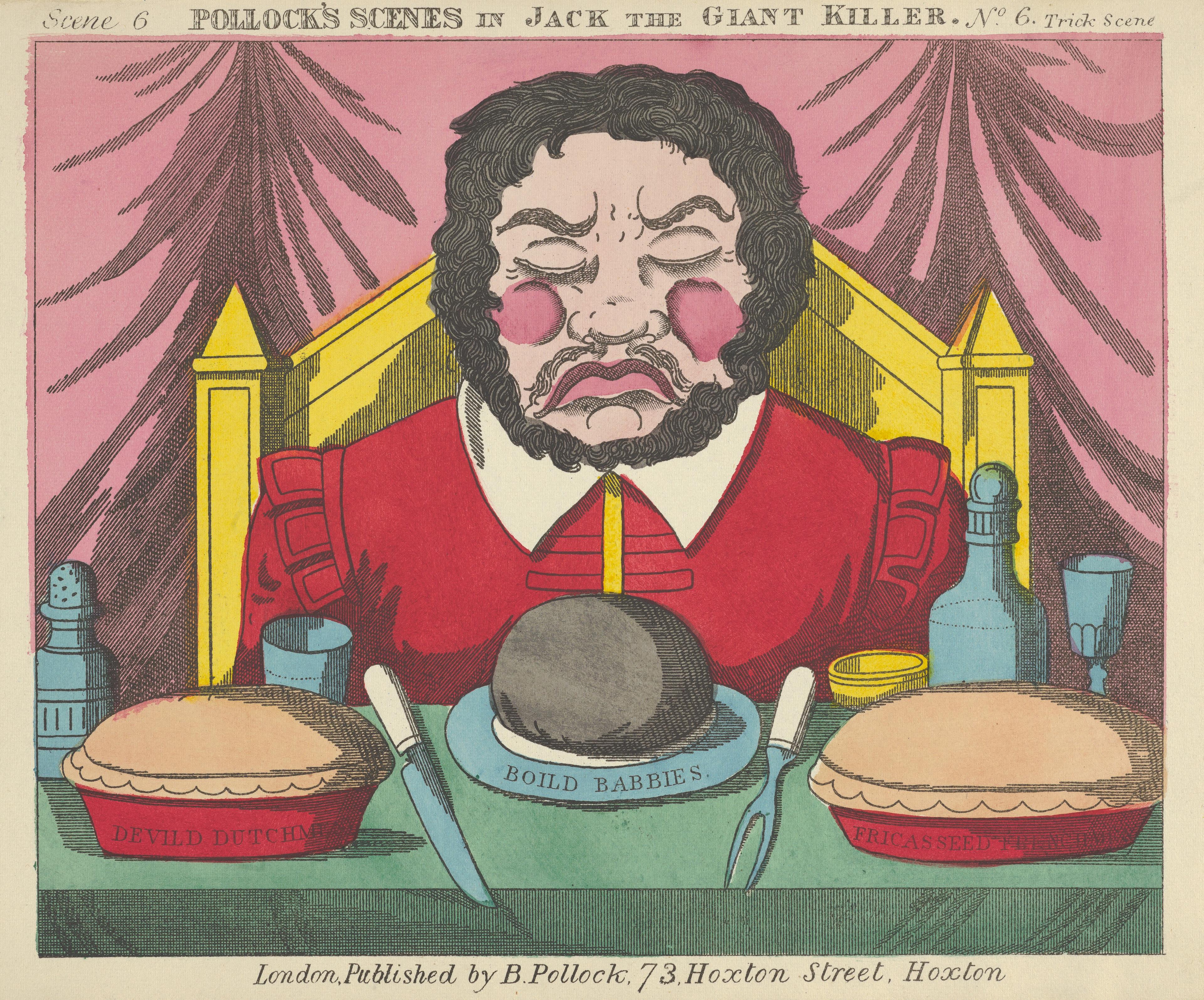

In the West, the nineteenth-century invention and widespread adoption of color lithography caused an exponential growth in the production of paper dolls for various functions. They were used in political satire, featured as pop-ups in books, employed as educational and advertising tools, and acted as performers in paper theaters.

Published by Benjamin Pollock (British, 1857–1937). Scene 6, from Jack and the Giant Killer, Scenes for a Toy Theater, 1870–90. Lithography, 6 3/4 x 8 1/2 in. (17 x 21.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1952 (52.541.1(14))

The most familiar paper dolls, however, are probably the individual figures used as children’s toys to dress and play with. These historically coexisted with other types of dolls—including the popular wood, mechanical, and porcelain models—but paper dolls were far more prevalent across various social strata. Relatively inexpensive and efficient production methods enabled publishers to print these dolls in large quantities and sell them for pennies per set. This meant that, unlike their more expensive equivalents in porcelain or bisque, paper dolls were affordable to a much broader group of children. They were often sold in sets on uncut sheets of paper or cardboard featuring a doll surrounded by numerous costumes. The sets could be bought in toy stores or directly through their publishers.

One of the first paper dolls to be commercially manufactured was “Little Fanny”—the main character of The History of Little Fanny (1810). This short book, published by S. & J. Fuller at the "Temple of Fancy" in London, tells a moral tale about a girl who disobeys her mother and runs away from home. Her decision leads to numerous misfortunes, but through hard work she comes to regret her actions and eventually returns home, morally transformed. Seven cut-out figures representing Fanny’s body and clothes, one head, four hats, and a cardboard slipcase accompany the book, illustrating its narrative. Each chapter begins with instructions on how Fanny should be dressed, allowing the reading child to match the appropriate outfit to the doll’s head.[6, 7]

Paper dolls not only reflected the desired moral lessons a girl was meant to learn but also actively shaped them.

With the advance of the nineteenth century, paper dolls appeared in women’s and children’s magazines and newspapers, becoming a marketing tool due to their growing popularity. Publishers would feature one or two dolls in an issue and follow up with additional costumes and family members in subsequent editions to encourage continued readership. The effectiveness of this strategy is evidenced in newspapers such as the Boston Herald, the Boston Globe, and the Boston Post, which competed for readers in the early 1910s by launching their own paper-doll series.[8]

Building on the appeal of seriality and collectors’ desires to complete a set, various companies began using paper dolls in advertising. This practice reached its peak between 1890 and 1920, with hundreds of paper dolls produced by companies and brands such as Singer (sewing machines), Lyons (coffee), Pillsbury, and Baker’s Chocolate.[9] These companies would add one doll of a set to their product’s packaging, with clear instructions on how to obtain the rest. The same strategy, albeit with different types of toys, is probably familiar to many from McDonald’s Happy Meals or Kinder Eggs.

Tailor and Bed, from Sunshine Paper Dolls, May 14, 1916. Offset lithograph, 8 × 13 in. (20.3 × 33 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mr. and Mrs. Robert J. Massar Gift, 1973 (1973.558.10)

Dolls came in various shapes and sizes. Some had movable joints, while others were static. In some cases, like Fanny’s, the dolls were reduced to heads that could be attached to bodies in different ways. The mechanics of the accompanying paper costumes also underwent various transformations. Most familiar and still in use today are the little paper tabs that fold around the body of the paper doll at strategic points, which were invented in the late nineteenth century. Their introduction by the McLoughlin Brothers, Inc.—a New York publishing firm that developed unique color printing technologies in children’s objects like books, games, and paper dolls between 1858 and 1920—significantly contributed to their popularity.[10] Prior to this innovation, dresses could be folded over the body, placed next to the doll’s head, or designed with a hole for the head to be put over the doll. A good example of the latter method found in The Met collection are the dresses made by Elizabeth S. Tucker for her set Famous Queens and Martha Washington (circa 1895), in which three dresses accompanied each queen. Tucker’s dolls introduce another important dimension: many were created not only for women but also by women.

Left: Published by Littauer and Boysen. Ballerina and Bloomer Girls (Prima Donna) Paper Dolls, 1890–1905. Lithograph, 14 3/8 × 6 1/8 in. (36.5 × 15.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of D. Lorraine Yerkes, 1959 (59.616.403a-g). Center: Elizabeth S. Tucker (American, late 19th century). Queen Louise Court Robe, ca. 1895. Color lithograph, 7 1/8 × 2 1/8 in. (18 × 5.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession Jean Mailey, 1983 (1983.1151.16). Right: Elizabeth S. Tucker (American, late 19th century). Queen Louise Reception Gown , ca. 1895. Color lithograph, 5 3/8 × 2 1/8 in. (13.5 × 5.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession Jean Mailey, 1983 (1983.1151.14)

In contrast to their inexpensive materials and commercial production methods, however, paper dolls promoted upper-class fantasies. One example publishers proliferated during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries is the idyll of the middle- or upper-class white family. Such paper families usually revolved around a little girl, who would be accompanied by her siblings, parents, friends, and servants. Besides family members and refined costumes, such doll sets often came with furniture, accessories, sports equipment, and sometimes even houses.

Kitchen Background, from Dolly at Home , ca. 1870. Color lithography on paper mounted on cardboard, 7 3/8 × 9 5/8 in. (18.5 × 24.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1954 (54.523.6(8))

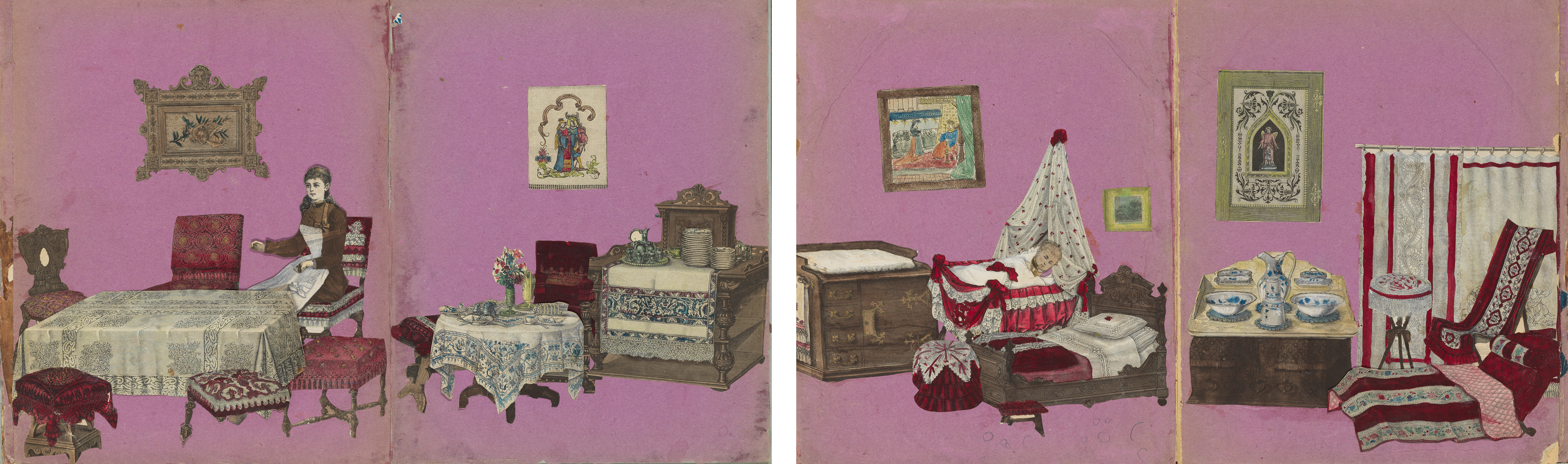

A beautiful example of an assembled two-dimensional dollhouse can be found in the Museum's drawings and prints collection. While neither the owners nor the creators of this house album are known, we know that paper houses of this kind were generally made as a pastime by women and children, while men usually made wooden dollhouses.[11] Thus, paper dolls illuminate both the works of overlooked women artists but also speak to the creativity of anonymous women who made them to entertain themselves and their children. The Met’s paper dollhouse is mounted on the empty pages of an 1883 Geschäfts-Kalender (office calendar). Every page spread represents a different interior of a luxurious home including a parlor, nursery, bedroom, and boudoir. The family’s wealth is reflected in the paper imitations and reproductions of refined carved wooden furniture, lavish textiles like lace and brocade, porcelain chamber sets, and numerous paintings. The result is a visual feast of dazzling objects and exquisite details. While most objects were probably cut from designated sets, some were homemade. The unknown creators also hand-colored certain pieces, thereby personalizing them to their own taste. This house comes with a family of dolls, which includes two men, various women, and several young girls. Curiously, the dolls are not intact; instead, the heads and bodies are provided separately, with far fewer heads than bodies. This means that the heads were likely meant to be placed on different bodies at different times, enabling changes of costume and identity. The different scales of the dolls suggest that at least some of them originally came from different sets.

Left: Anonymous, German, 19th century, Paper Doll Dining Room, 1883. Wood engravings, printed paper, cut out, hand colored and assembled, 11 in. × 17 3/8 in. (28 × 44 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1970 (1970.565.136(7)). Right: Anonymous, German, 19th century, Paper Doll Nursery, 1883. Wood engravings, printed paper, cut out, hand colored and assembled, 11 in. × 17 3/8 in. (28 × 44 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1970 (1970.565.136(3))

Despite its delicate nature, this house was originally made for play. To facilitate this, some of the furniture was folded or cut in special ways, creating spaces to insert the paper dolls. For instance, a baby’s crib has a slit to accommodate a baby’s head, and a corner of a table is loose to allow a sitting doll to be placed behind it. This house, with its various paper accommodations, represents a remarkable attempt to represent three-dimensional space in two dimensions. The use of printed images arranged in overlapping planes and the ability to manipulate the figures within the space results in a visually compelling solution. When flipping through the pages of this dollhouse, we see how fantasies of prosperity and domesticity were personalized and reenacted.

A famous example of a “paper perfect family” is the Lettie Lane Paper Family, created by another forgotten woman artist, the American illustrator Sheila Young. Young was a famous paper-doll artist who is known to have worked up until World War II.[12] From 1908 until 1915, she published her Lettie Lane series in the Ladies’ Home Journal. The paper family consisted of Lettie, her friends and family, and their servants.[13] The Met has four uncut sheets from the series: two are devoted to Lettie’s siblings (her twin brother, sister, and baby sister), and two feature Lettie’s dolls. All are accompanied by an array of clothes and accessories. Lettie’s baby sister, for example, is dressed in a long petticoat, joined by a nurse, and surrounded by pastel-colored belongings such as a canopy bed with light blue ribbons, coats, dresses, and toys almost as large as the baby herself. Prosperity and wealth are everywhere. The well-cared-for children want for little, and their smiling faces radiate tranquility.

Left: Sheila Young (active early 20th century). The Lettie Lane Paper Family: Presenting One of Lettie's Dolls, With Her Hats and Dresses, 1909. Lithograph, 15 1/4 × 10 1/8 in. (38.8 × 25.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Douglas S. Brown, 1967 (67.778.180). Right: Sheila Young (active early 20th century). The Lettie Lane Paper Family: Presenting Lettie's Dolls' Party of Little People Dressed in Fancy Costumes, 1909. Lithograph, 15 1/4 × 10 1/8 in. (38.8 × 25.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Douglas S. Brown, 1967 (67.778.181)

The Lettie Lane Paper Family clearly demonstrates the gendered presentation of the ideal paper families of this era as well. Girls were presented alongside their toys in domestic interiors, while boy dolls were designed to enjoy outdoor activities. The life path of a paper girl moved from an idyllic childhood to matrimony and, finally, to childrearing. The peak of this journey was her wedding day, in which she was printed alongside exquisite bridal gowns.

Curiously, paper dolls had their own “army” of dolls. The sheet titled “Presenting Lettie’s Dolls’ Party of Little People Dressed in Fancy Costumes” shows twelve male and female dolls dressed in elaborate costumes, including muffs, fur coats, and a variety of plumed hats. The prevalence of dolls in the paper girl’s life is a comment on the role dolls were expected to play in children’s lives more generally. By the end of the nineteenth century, psychologists like the American G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924), who is considered the founder of child and educational psychologies, argued that doll play allowed the female child to reenact the values and lessons she learned at home. Doll play was viewed as a rehearsal for the girl’s future as a mother. Yet paper dolls not only reflected the desired moral lessons a girl was meant to learn but also actively shaped them. They represented not “what [doll-players] could obtain but what they were supposed to admire and desire: a secure life of domestic bliss made possible by capitalist and moral success.”[14]

Today, paper dolls have been largely replaced by their digital counterparts. Unlike other types of games where players dress their avatars for a variety of purposes, dress-up games focus on fashion choices as the game’s essence: Time Princess, Fashion Dreamer, and the viral Dress to Impress all invite players to design outfits for digital dolls.[15] The more outfits and accessories a game offers, the higher its perceived value. Fashion brands like H&M have also introduced “virtual fashion shops” where they can host virtual fashion campaigns and customers can virtually test something they want to purchase or acquire digital-exclusive wear for their avatars. Similar to historical paper dolls or contemporary digital games, users can style their avatars virtually. Unlike video games, however, these dress-up experiences are not designed for gaming but instead enable customers to outfit their digital proxies for use in virtual spaces. On one hand, the abundance of options allows players to simultaneously embody the roles of creative designer and stylish fashionista. On the other, this emphasis on consumption and the rapid replacement of items mirrors and glorifies the contemporary practice of ultrafast fashion.

Although many are familiar with online dress-up games and the growing interest in digital fashion, fewer are aware of their paper predecessors. Yet these modest objects deserve our attention. Beyond being affordable and entertaining toys, paper dolls carry significant cultural and historical value. They reflect the beliefs of the societies in which they were created, embodying both their aspirations and prejudices. Moreover, they honor their creators: nearly forgotten women artists and countless anonymous women and children who made and played with them. Though much time has passed since I cut and glued my paper carriage, its memory remains part of a rich tradition of paper creations—rooted in ancient China and evolving toward a future in the metaverse.

Notes

[1] Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene, Paper Dolls: Fragile Figures, Enduring Symbols. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, 2017. p. 6

[2] Brian Sutton-Smith explores the intricate connections between play and ritual in his book The Ambiguity of Play. Brian Sutton-Smith. The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997.

[3] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 10-14.

[4] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 14.

[5] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 16-18.

[6] “The History of Little Fanny,” The University of Southern Mississippi, Special Collections, accessed November 25, 2024, https://www.lib.usm.edu/spcol/exhibitions/item_of_the_month/iotm_sept_08;

[7] “The History of Little Fanny,” CSUN University Library, October 15, 2024, https://library.csun.edu/sca/peek-stacks/fanny.

[8] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 79-80.

[9] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 79-80.

[10] More about the McLoughlin Bros. see: Laura Wasowicz. “McLoughlin Bros. Collection,” American Antiquarian Society, last accessed August 9, 2024, https://www.americanantiquarian.org/mcloughlin-bros.

[11] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 97-98.

[12] For example, see: Sheila Young. Lettie Lane's great grandparents: a book of dressing dolls, London [Ernest Nister] and New York [E. P. Dutton], [188-?]. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge (MA) available online at https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:11693943.

[13] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 88.

[14] Adams and Keene, Paper Dolls. 92.

[15] Designed by Roblox and released in October 2023, “Dress to Impress” offers a competitive game where players are expected to compete one another for the best design. This game exceeded regular fans of dress up games and entered the mainstream, after being played over 2.7 billion times.