Alexander Phimister Proctor with his daughter Nona Proctor Church's children, Christmas 1942. Sandy is on his lap; behind Proctor (left to right): Betty Jean, Campbell Scott, and Peggy Ann. Photograph. The Proctor Foundation, Hansville, Washington

The self-proclaimed "Sculptor in Buckskin," Alexander Phimister Proctor (1860–1950) was born in Ontario, Canada, and raised in Denver, Colorado. At the age of twenty-five, he moved to New York to study at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League, and he later trained in Paris at both the Académie Julien and the Académie Colarossi. Proctor is best known for his sculptures of American Indians, cowboys, and wildlife carried out in a sophisticated, French Beaux-Arts style. Inspired by his experiences as an avid hunter and outdoorsman, he often approached animal subjects from a scientific perspective, undertaking dissections and studying specimens at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

In 1891 Proctor was commissioned to create thirty-five lifesize sculptures of western animals, and subsequently a pair of equestrian statues depicting an American Indian and a cowboy for the grounds of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The success of these works established the artist's reputation as a leading American sculptor, and he won numerous monumental commissions over the course of his career. Today, Proctor's monuments are found in cities across the United States, from Washington, D.C., to Portland, Oregon. Seven of his bronze statuettes are currently on view in The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925, making him one of the most represented artists in the exhibition.

I had the privilege of speaking with Phimister Proctor "Sandy" Church, the grandson of Alexander Phimister Proctor, when he and his family visited the Met for the opening of The American West in Bronze. Sandy shared his memories of growing up with Proctor, and we discussed his lifelong passion for collecting Proctor's work and educating the public about his grandfather's life and legacy.

Shannon Vittoria: You introduce yourself as Sandy, but you were named after your grandfather, Alexander Phimister Proctor.

Sandy Church: Yes, my mother, Nona Proctor Church, was the daughter of Alexander Phimister Proctor, and she named me after Granddad. The name Phimister was a little tough in grade school, so I picked up the nickname Sandy.

Shannon Vittoria: Were you close with your grandfather?

Sandy Church: We had a very special relationship. When I was born, Granddad wrote in a letter to my mother that he was "tickled" to learn that I had been named after him. He also understood that I looked like him, and wrote to her, "Oh, the poor fellow. What he will have to live up to!" He closed the letter by saying, "Of all my grandkids, when I saw Sandy, he reached out and held me like none of the others." We had a close connection that began early in my life.

Shannon Vittoria: When you were five years old, your grandfather came to live with your family. Can you share some of the memories you have of him from this time?

Sandy Church: It was 1942 when Granddad came to live with my family in Laurelhurst, Seattle. He had just lost his wife, Margaret—or Mody, as we called her. My feeling is that the love he had devoted to her for forty-eight years, he turned and poured into me. I was only five years old at the time, and he was eighty-two, but we had this amazing bonding experience. He was a kind man, but he loved playing tricks. In the backyard, he would have me run by him like a galloping horse and he would then lasso my foot right out from under me, causing me to spill and laugh. He taught me how to lasso, and he told great stories about the Old West—tales of cowboys and Indians, hunting, and climbing mountains. He also had a headdress and a peace pipe given to him by Chief Little Wolf of the Northern Cheyenne, and I remember him showing me these artifacts and sharing their history with me.

Alexander Phimister Proctor (American, born Canada, 1860–1950). Phimister Proctor "Sandy" Church (five years old), 1941. Plaster. The Proctor Foundation, Hansville, Washington

Shannon Vittoria: Did you and your grandfather ever talk about art?

Sandy Church: Well, I was a young boy and we never really talked about art, but his sculptures were always surrounding us in our home. He stayed with us for about a year, and then moved to Palo Alto in 1943. Before he left, Granddad sculpted a bas-relief portrait of me in my coveralls—the same coveralls I'm wearing in an old photograph of me sitting on Granddad's lap [see above]. He modeled the work in clay in our living room and I had to sit still for him for what felt like years. Later in life, when I was given his original tools, I could still smell the clay on them. This smell brought back the memories of me sitting and fidgeting for hours as he created this portrait.

Shannon Vittoria: When did you begin to take a more serious interest in your grandfather's work, as a collector and as a historian?

Sandy Church: I was about twenty years old and I had just graduated from the University of Washington. I made a commitment to collect one of each of Granddad's bronze statuettes. At the time, I didn't realize that there were more than fifty of them! A few years later, with the help of my mother, I purchased my first sculpture, Proctor's Morgan Stallion of 1913 [see another example]. Over the years, I continued to collect his bronzes, and it became a great love and passion of mine. I also began collecting his plasters, paintings, etchings, and scrapbooks. At first, I put everything in my office, but I quickly ran out of room and had to take over a 2,000-square-foot space that we kiddingly called "the Proctor museum."

Shannon Vittoria: This museum soon became a reality, however.

Sandy Church: Yes, I started waking up to what I really had, and I soon realized that this was an important collection and one that needed to be properly maintained. In 1997, I established the A. Phimister Proctor Museum and the Proctor Foundation in Hansville, Washington, in order to promote and preserve Granddad's work. Then in 2005, I donated the majority of the Museum's collection to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. My daughter Laura Proctor Ames, who is now the Director of the A. Phimister Proctor Museum, is carrying on my passion, and together we continue to educate people about Proctor and his art.

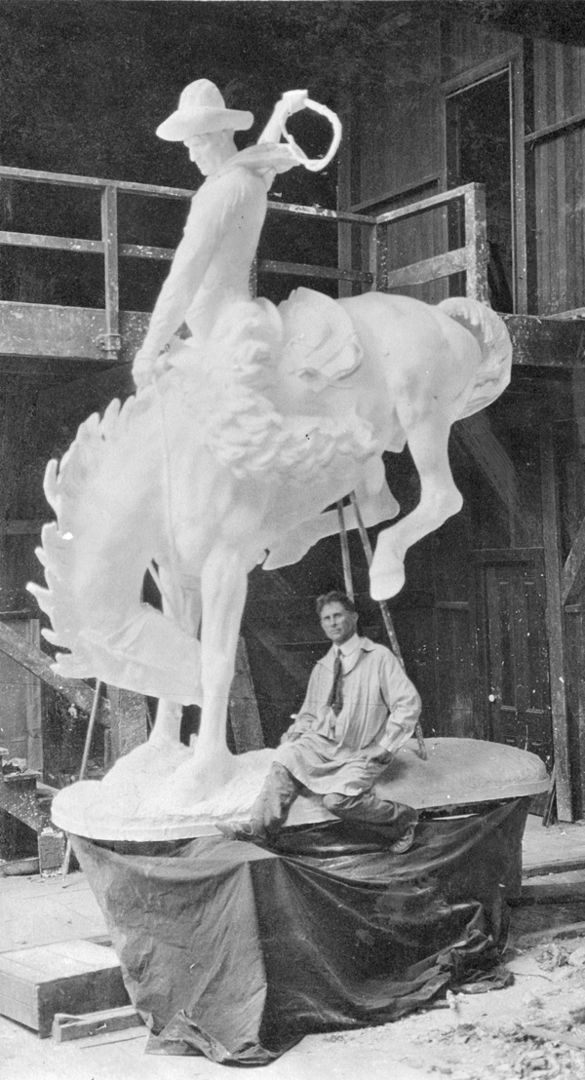

Proctor with His Monumental Plaster Broncho Buster, Los Altos, California, 1919. Contact print, 4 3/4 x 3 1/4 in. (12.1 x 8.3 cm). Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, Gift of Phimister and Sally Church

Shannon Vittoria: As you collected his sculptures over the years, what were you most surprised to learn about your grandfather?

Sandy Church: There are a handful of sculptors in this country who are household names—Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French, for example. Yet when I would talk about Granddad, I was shocked to learn that many people didn't know who he was. I would ask them if they had ever seen the four Buffalo (1914) on the Q Street (Dumbarton) Bridge in Washington, D.C. or the Broncho Buster (1919) monument in Denver, and they would say, "Oh, yes, of course. Your grandfather did that? I always thought that was Remington!" Although museum curators and art historians knew Proctor, I was surprised that the public didn't know him. I felt it was my duty to carry on his legacy, and I embarked on this journey to bring his art and his life story to the forefront.

Alexander Phimister Proctor (American, born Canada, 1860–1950). Indian Warrior, 1898 (cast 1913 or after). Bronze, 39 1/4 × 29 1/2 × 9 1/4 in. (99.7 × 74.9 × 23.5 cm). Daniel and Mathew Wolf, in memory of Diane R. Wolf

Shannon Vittoria: Seven of Proctor's sculptures are featured in the Met's installation of The American West in Bronze. Do you have a personal favorite among these works?

Sandy Church: Granddad's Indian Warrior (1898) has always been one of my favorites. He based the figure on a man named Weasel Head, whom he met when visiting the Blackfoot Reservation in Montana. It is an image of a magnificent, proud, dignified Indian, who holds his head high. There is a nobility to the work that I admire, and a sense of simplicity. He didn't overwhelm the work with details, but instead created a clean, simple, and elegant sculpture. Dignity, nobility, and simplicity—these were three principles that guided his art throughout his career.

Shannon Vittoria: Authenticity also played an important role in his work, especially when modeling animal wildlife.

Sandy Church: Yes, Granddad was a great hunter and outdoorsman. He hunted in conjunction with his art, and if he killed a deer, an elk, or a moose, he would dissect the animal to better understand its anatomy and muscle structure. When he was working on Stalking Panther (1891–93) while living in Paris, he adopted a stray alley cat and brought it back to his studio to study the musculature of the cat in motion in order to improve upon his plaster. He ended up keeping the cat and took care of it for years. When he finished Stalking Panther, he put the bronze on the living room floor and he described the cat coming around the corner, seeing the sculpture, jumping up in the air and then running away in fear. It was a successful work!

Alexander Phimister Proctor (American, born Canada, 1860–1950). Stalking Panther, 1891–93 (cast ca. 1905–13). Bronze, 10 1/4 x 31 x 4 1/2 in. (26 x 78.7 x 11.4 cm). Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Bequest of James Parmelee (41.79)

Shannon Vittoria: How would you like people today to remember your grandfather?

Sandy Church: Granddad was a man with three passions in his life: sculpting, hunting, and family—although I wouldn't be able to tell you which of these came first, second, or third. He should be remembered for these three passions, as they defined his life and his art.

To learn more about the life and work of Alexander Phimister Proctor, visit http://www.proctormuseum.com/.

Additional Reading

Hassrick, Peter H., et al. Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor. Exh. cat. Fort Worth, Tex: Amon Carter Museum; London: Third Millennium Publishing, 2003.

Proctor, Alexander Phimister. Sculptor in Buckskin: The Autobiography of Alexander Phimister Proctor. Edited by Katherine C. Ebner; foreword by Peter H. Hassrick. Rev. ed. 1971. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

Tolles, Thayer, Thomas Brent Smith, et al. The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.