At the turn of the twentieth century, on the southern coast of Papua New Guinea’s Massim region, an unlikely friendship formed between a Suau master carver and an English evangelical missionary. Mutuaga (ca. 1860–1920), known as Oitau (carved man) to Suau people because of his mastery of his art, developed a sculptural style of refined naturalism that elaborated more simple figures previously carved for utilitarian purposes and magical efficacy into standalone works of art. Reverend Charles Abel (1863–1930) was a minister with the London Missionary Society who established a longstanding mission at Kwato, Milne Bay, and became a friend and patron to the artist. The period in which the two men met was one of rapid and significant change through the colonization and missionization of Papua. Among the legacies of their relationship is a rare corpus of artworks by a named Papuan artist, including one lime spatula in The Met collection (2008.571). A recent collaboration between The Met and the Massim Museum and Cultural Centre in Alotau, Milne Bay, is helping shed new light on this piece and Mutuaga’s legacy in the Massim region today.

Though Mutuaga’s artistic career spanned four decades, and he produced a body of almost one hundred known works, little is known of his life. Believed to have been born around 1860, Mutuaga of the maliboi (flying fox) clan lived in Dagodagoisu village on the mainland of present-day Milne Bay Province. He was therefore a young man when the first mission was established in the region in 1877, and when the Australian colony of Queensland annexed the Territory of Papua for the British Empire in 1883. His contemporaries recalled him as a man of high standing in the community, with a reputation that extended well beyond his village. In 1914, the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski recorded that he sat and spoke with the master carver in the Suau region (the area on the south coast of the mainland Massim district) but gave little indication of what they discussed. Mutuaga was prolific as a carver—the corpus of his known works includes lime spatulas, freestanding figures, walking sticks, presentation axe handles, and headrests. When Charles Abel arrived at Suau in 1891, Mutuaga was in his early 30s and Abel himself was only a few years younger, making them peers. Indeed, Charles Abel’s children remembered the artist as a regular visitor to the mission house at Kwato, often making the 120-kilometer round trip by canoe to present his carvings in exchange for European goods such as kerosene, tobacco, metal knives, rice, and tinned fish.

Mutuaga, 1860–1920, Lime Spatula. Wood, lime, H. 24 1/2 × W. 3 1/8 × D. 3 5/8 in. (62.2 × 7.9 × 9.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Dr. Oliver E. and Pamela F. Cobb, 2008 (2008.571)

A lime spatula from The Met collection is typical of the naturalism and precision of Mutuaga’s sculptural style. Its oversized blade is topped with a human figure finial with hands clasped at its chest and elbows resting on bent knees. Incised designs of rolling scrolls follow the contours of the figure’s face, shoulders, and buttocks. Mutuaga packed these lines with mineral lime powder to contrast in bright white against the black stained wood. The piece was attributed to Mutuaga by the late scholar Harry Beran, who wrote the most comprehensive account of the artist’s life and compiled a catalogue of his known works. Beran’s research identified the spatula in The Met collection as one that had been in the possession of the Abel family in Wellington, New Zealand, before it appeared on the secondary market. In 2023, The Met partnered with the Massim Museum to record community reflections about Mutuaga and other Massim works in the collection. Among the Massim Museum’s interlocutors was Charles Abel’s great-great-grand-daughter, Bella Abel, who commented that the engravings on the body refer to woven armbands worn by men and women at the time. The facial markings likely refer to ceremonial face paint worn by men rather than tattoos, as only women were tattooed in the Massim region. Elements of the facial and body carving further reveal the individualization of the artist’s style. The etched almond-shaped eyes and lines curling up from either corner of the figure’s mouth are seen across many of his representations of the human form.

Lime spatulas facilitate the consumption of powdered lime, the active ingredient that maximizes the stimulating effect of betelnut when it is chewed. Today, almost 80% of Papua New Guineans chew betelnut, the seed of the Areca palm. The seed is chewed along with the fruit or leaf of the betel plant and mineral lime produced from burnt coral to create an effect similar to that of nicotine—imparting a sense of well-being and clarity, and a reduction in hunger. Lime spatulas, as the name indicates, are used to collect lime powder from a container. The spatulas themselves can be prized personal possessions and were often traditional ceremonial valuables. The turtleshell gabaela (1979.206.1464) from the Louisiade Archipelago that lies to the east of the Massim mainland serve as spatulas as well as supports for red shell money disks that are attached on string through holes drilled along the curved upper edge of the spatula’s blade. With disks still attached, gabaela are valuable enough to buy land, canoes or pay bride wealth. The “clapper” style of lime spatula (89.4.768) has a hollowed section of its handle that makes a loud clapping sound when struck against the body and can be used as a musical instrument, as well as by sorcerers to control elements of the natural and human worlds. Spatulas with human figure handles were made in the region well before Mutuaga was working in the style. These human figures were also associated with magic and could be used by ritual specialists who called on spirits to inhabit the figures and provide protection. Spatulas were also used in spells performed when carving canoe prows, fighting, and calling the wind when out at sea. Massim elders consulted by the Massim Museum identified a human figure finial at The Met that has been separated from its blade (1978.412.1503) as being connected with the magic of abundance, used by powerful gardening magicians to ensure a plentiful harvest.

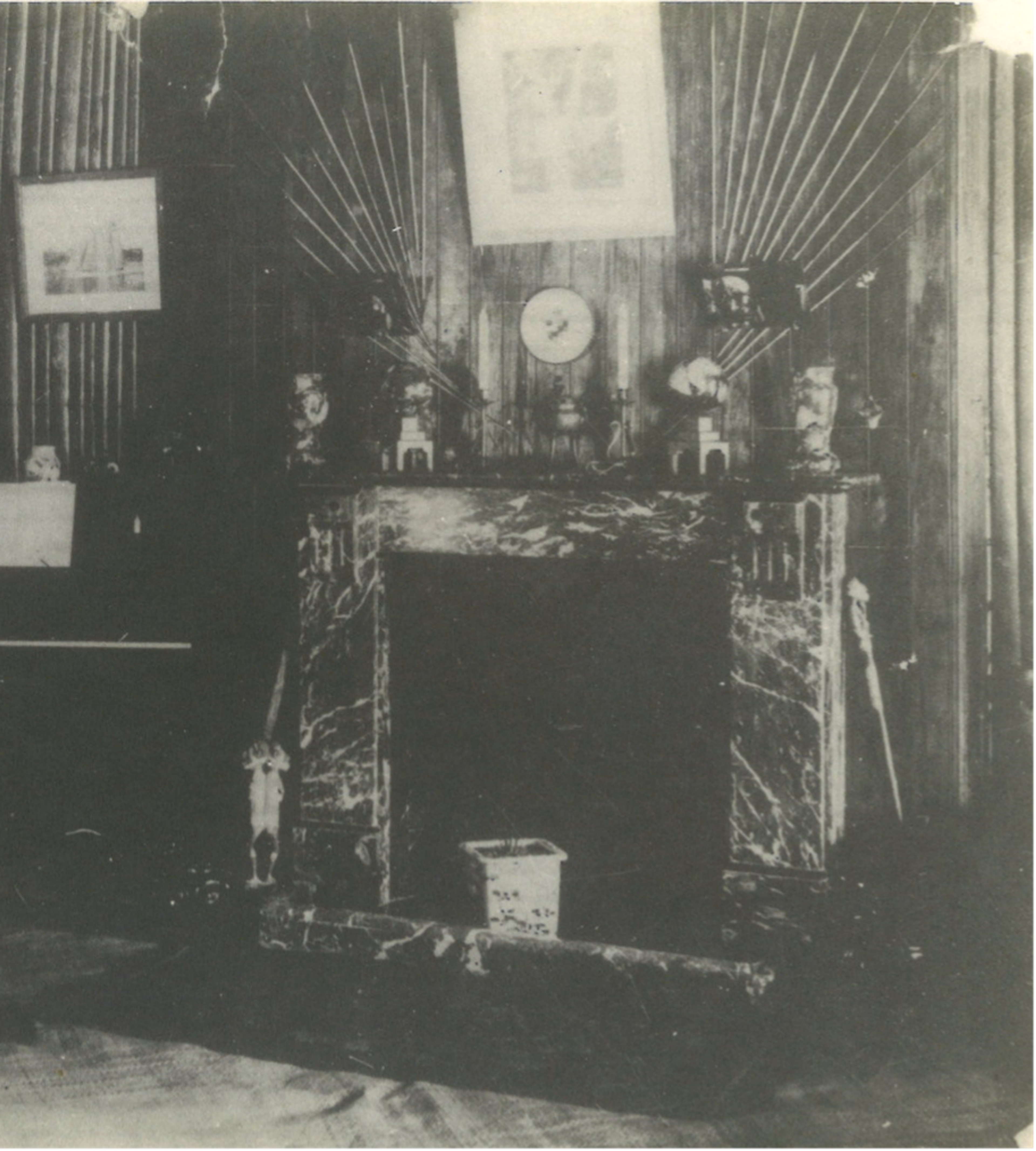

In contrast to these other examples, the Mutuaga spatula in The Met collection is too large to have been used for the consumption of lime. Instead, it was likely made as a sculptural piece under Charles Abel’s patronage. According to Abel’s son, Cecil, the missionary encouraged Mutuaga to make freestanding human figures on pedestals, typically about 30–40 centimeters tall, which enlarged the figures that the artist was already carving on spatula finials. The exaggeration in the size of the lime spatulas themselves also allowed Mutuaga to elaborate greater detail in the features and figuration of his works, further refining his mastery of the human form. Abel collected many of these pieces, displaying them in his home before giving many away to friends and family over time. Photographs from the mission house in Kwato at the time show an oversized spatula leaning against a fireplace with a freestanding carving of two figures standing back-to-back on the ground nearby.

Photograph of the fireplace at the Mission house in Kwato, date unknown. Image from the Abel Papers in the Michael Somare Library at the University of Papua New Guinea

Abel’s patronage of Mutuaga’s carving stemmed not only from his admiration of the maker’s talent, but also aligned with his evangelical interests. The first missionaries from the London Missionary Society had arrived in eastern New Guinea in 1877 from the Loyalty Islands (present-day New Caledonia). These Pacific Islander teachers attempted to convert the local populations but due to disease, the environment, and local politics, none remained by 1891 when Abel arrived and established Kwato as the central mission station. Like many European colonial officials and missionaries of the era, Abel was schooled in social Darwinism and evolutionary theory. He believed that Papuan cultures and practices would inevitably be eroded though contact with what he viewed as more advanced European practices, and that philanthropic support was needed for Papuans to compete with the foreigners increasingly present in the region. Among Abel’s aims at the Kwato Mission was to refocus customary arts into manual arts and skills that would be suited to a more European society. The early generations of converts received training in carpentry and boatbuilding alongside their religious education. Many of the Mission’s strategies would be considered unacceptable in contemporary times, such as the policy of removing children from their families and village life at a young age to be educated entirely within the church system.

While Abel’s encouragement of Mutuaga’s carving as a commercial enterprise fit clearly within what he saw as the civilizing aims of the Mission, the role that the carvings themselves played within the system is less obvious. The prior associations of carved human figures with sorcery in Milne Bay were antithetical to the objectives of the church, which staunchly opposed idolatry and magic. It is well documented that earlier in the nineteenth century, the London Missionary Society captured and collected so-called idols across Polynesia as evidence of their evangelical success in converting local people who surrendered and destroyed their "false gods." Abel and his contemporaries in Papua such as John Henry Holmes took a somewhat different approach toward Papuan religion, seeing local cultural and ceremonial practice less as examples of idolatry, but rather as evidence of the capacity for religious thought, and therefore, Christian potential. Hence, Abel encouraged the production of art that could be cast within a Christian light. Indeed, he had a collection of Mutuaga’s freestanding sculptures at his house that he dubbed the twelve apostles, even though they were never used in religious ceremony. The collection sat on the bookshelf in the Abel family “Big House” for many years.

We will never know what Mutuaga thought about the adoption of his carving in this context. From his fieldwork in 1993, Harry Beran noted that according to fellow carver, Weibo Mamohoi, Mutuaga never converted to Christianity himself, but adopted the name Oitau, or carved man, underscoring his close relationship with carving and apparent identification (even personification) with the woodcarvings he created. Beran also observed that the artist’s nickname Oitau has other distinctly religious connotations—namely, that the Suau translation of the second commandment, “You shall not make a carved image of yourself,” is Oitau tabu uginauri. Across Milne Bay more broadly, oral traditions recall Charles Abel as a figure of powerful supernatural potency, revealing that the syncretism of religions went both ways, and that Massim people ascribed their own spiritual beliefs onto Abel’s missionary practice.

Freestanding Mutuaga statue, or “apostle,” donated to the Massim Museum by Sheila Abel. Image courtesy of the Massim Museum and Cultural Centre

Mutuaga’s legacy lives on in various ways today. His distinctive artistic style has led him to be remembered within Massim communities as one of the finest carvers of his generation and he is celebrated by museum curators and international scholars as a named Pacific artist—unique for the time he was working. Many of his works, including Abel’s “apostle” carvings, were distributed within and beyond the family and are no longer traceable. The last statuette that remained in the hands of the family was donated to the Massim Museum by the late Sheila Abel. The location of the other eleven statuettes is unknown. In 2023, Fidelma Saevaru of the Massim Museum attempted to contact those within the community who had inherited knowledge and stories of Mutuaga. She found that though the artist is well remembered within museums and collections overseas, elders in the local community who still have knowledge of Mutuaga live outside of the regional capital Alotau and are difficult to trace. Mutuaga himself has no surviving descendants. He and his second wife Gaiomina had one son, Saliwowo, who was himself a carver but had no children. Charles Abel and his wife Beatrice had four children, some of whom remained at Kwato and married into the Suau community.

Mutuaga’s spatula at The Met is therefore a product not only of an artist-patron relationship, but also of innovation and adaptation by an artist in the face of sweeping colonial and missionary incursions into the Territory of Papua, and the meeting of two different belief systems. Christianity and magic continue to coexist in the Massim region. And even as lime spatulas are used less frequently by younger generations, they continue to be made and held by families for their spiritually efficacious properties.

The spatula will be returning on display at The Met when the Oceania galleries in the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing reopen in spring 2025.