This year marks my tenth as a volunteer in the department of Drawings and Prints, where I have been studying and cataloguing the Museum’s vast collection of historical valentines. As I continue mining the collection, my heart sings with each new discovery. One recent find was a trove of historical engraved rebus letters, many of which were valentines.

A rebus is a puzzle in which certain words, syllables, or sounds are substituted with pictures to create text that is a combination of pictures and individual letters. The reader must be able to recognize which words, syllables, and sounds the pictures are meant to represent to solve the puzzle and decipher its meaning. These mysterious missives were greatly popular in Europe from about 1650 and 1850.

Rebuses were the basis for modern-day writing. As early as 3400 BCE, ancient Egyptians were communicating visually using hieroglyphics—a type of rebus. From ancient hieroglyphics and cuneiform tablets to advertisements and games created today, the rebus has been an integral aspect of communication for millennia.

In seventeenth- through nineteenth-century Europe, rebuses constituted playful tokens of love and affection, and deciphering them was a popular parlor game among the intellectually minded. Some were easy to interpret while others required substantial cerebral skill, and the resolution of the challenge would only be revealed with great effort.

A highlight of The Met’s rebus collection is a fan by the Italian artist Stefano della Bella of 1639. It consists of a double-sided ovular paper base with etched pictograms surrounded by a luxurious, multicolored silk fringe, and a wooden handle attached to its base. An early example of a luxe European rebus, the fan would have inspired scholarly conversation and encouraged social entertainment. On one side, the images spell out a message related to love. On the other, they communicate a message about fortune. (Read a translation of both rebuses here). To complement the playful character of the rebus, the fluttering of the silk fringe would have fanned the user’s face and attracted onlookers’ attention.

Stefano della Bella (Italian, 1610–1664). A fan with a rebus on Love on one side Fortune on the other, ca. 1639. Etching fashioned to form a fan with fringe around the edges and wooden handle. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Estate of Florance Waterbury, 1970 (1970.610)

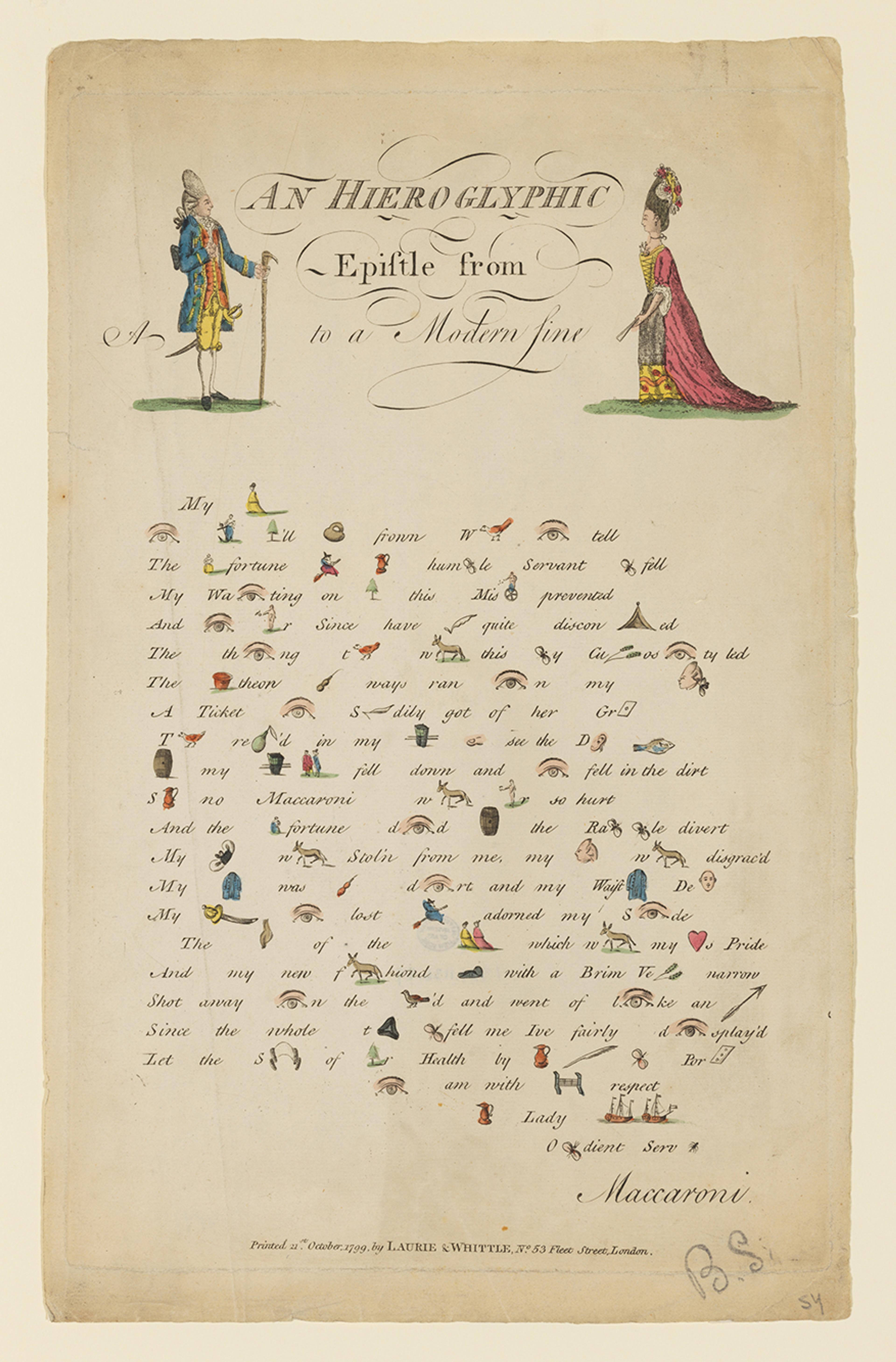

Most rebuses in the collection take the form of a letter. A British example published by the firm Laurie and Whittle in 1799 tells the amusing story of a fictitious author named “Maccaroni”—a kind of generalized pseudonym for the sender—whose attempts to court a “modern fine lady” resulted in a series of mishaps from falling in the dirt to losing his hat to the wind. In Georgian era England, cheeky, humorous rebuses like the one below were sold at stationers and served as a popular form of valentine. Although this example was published in England, it was written in French, and likely designed for the popular French market. (Read a translation of this rebus here).

Whittle & Laurie (British, active 1812–18). A Hieroglyphic Epistle Maker, October 21, 1799. Hand-colored etching, 15 × 9 1/2 in. (38 × 24 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.89)

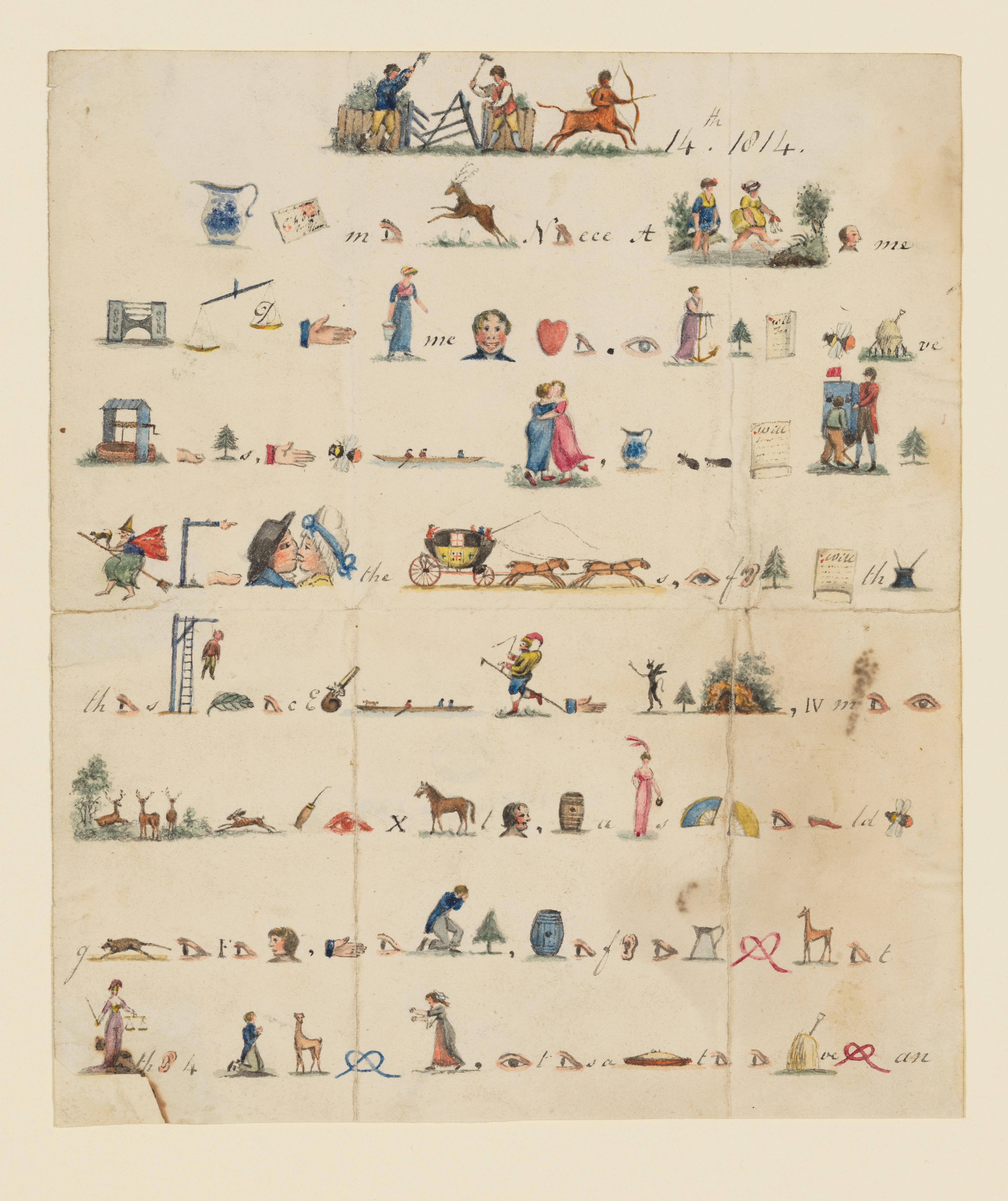

A most charming example in the collection, also British, is an 1814 letter sent by “Loving Uncle William Horndson” to his young niece regarding her upcoming visit. It includes tender watercolor images of hearts, a coach—which will meet her upon her arrival—and loving kisses. Rebus letters like this one were thought to make the act of reading more exciting and engaging. Indeed, in the eighteenth century, children were often taught about the Bible using rebus bibles in which words were replaced by images. In addition, prominent educators popularized the concept that children could eagerly learn to read through the use of rebuses.

Anonymous (British, 19th century). Rebus Valentine Letter, 1814. Pen and ink with watercolor, 8 1/4 × 7 1/8 in. (21 × 18 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.139)

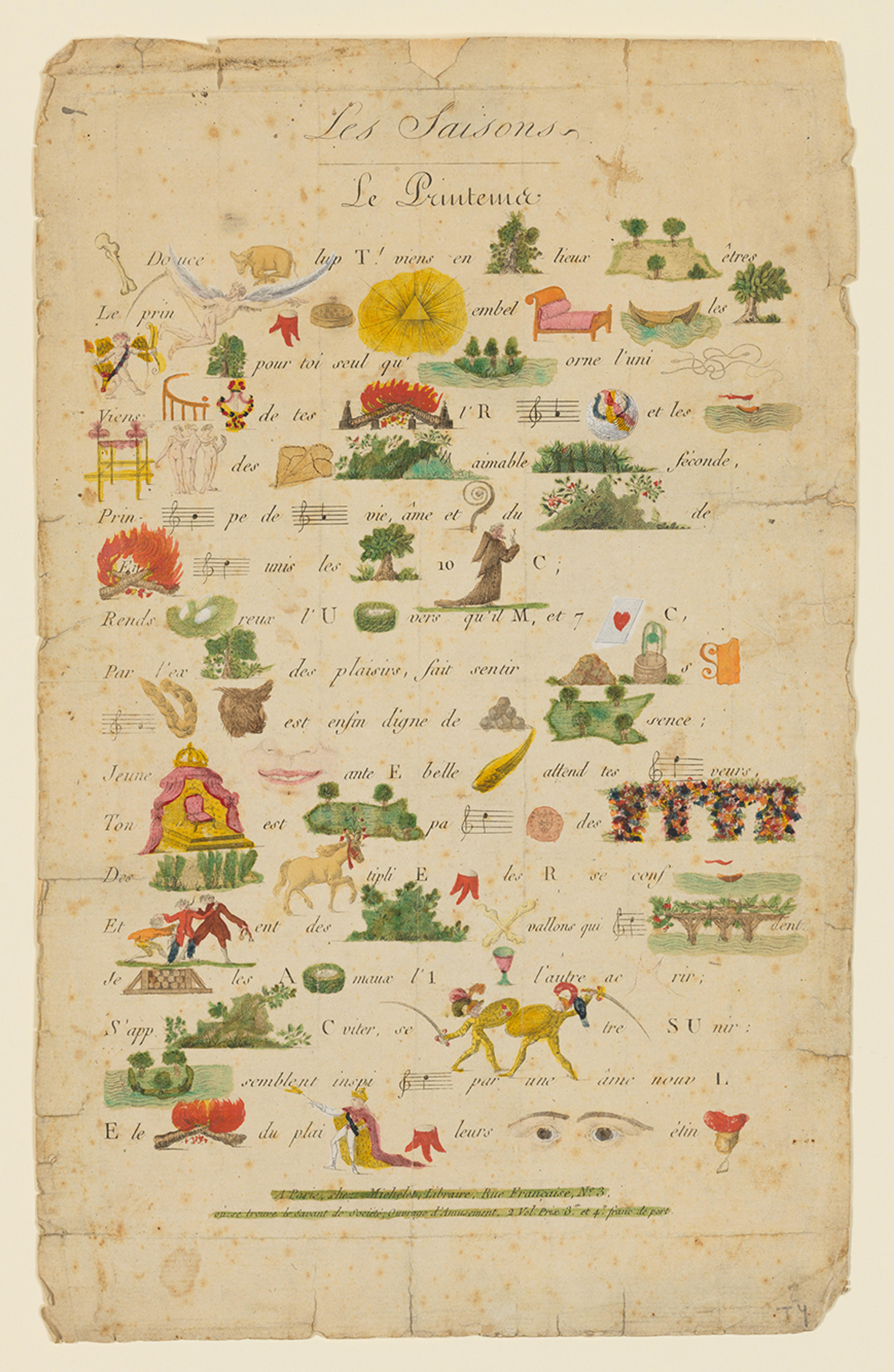

The Met collection includes several examples of rebus letters issued by the Paris-based publisher Michelet, which was active in the early nineteenth century. A wonderful engraved and hand-colored version from around 1820 is notable for its heavy use of pictures. The name and address of the publisher are inscribed at the bottom of the sheet, followed by the words “ou se trouve le savant de Societe Ouvrage d’Amusement,” which translates to “where one can find the scholar of Society Work of Amusement.”

Michelet (French). Les Saisons Rebus letter, ca. 1820. Hand-colored engraving with watercolor, 13 3/4 × 8 3/4 in. (35 × 22 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.138)

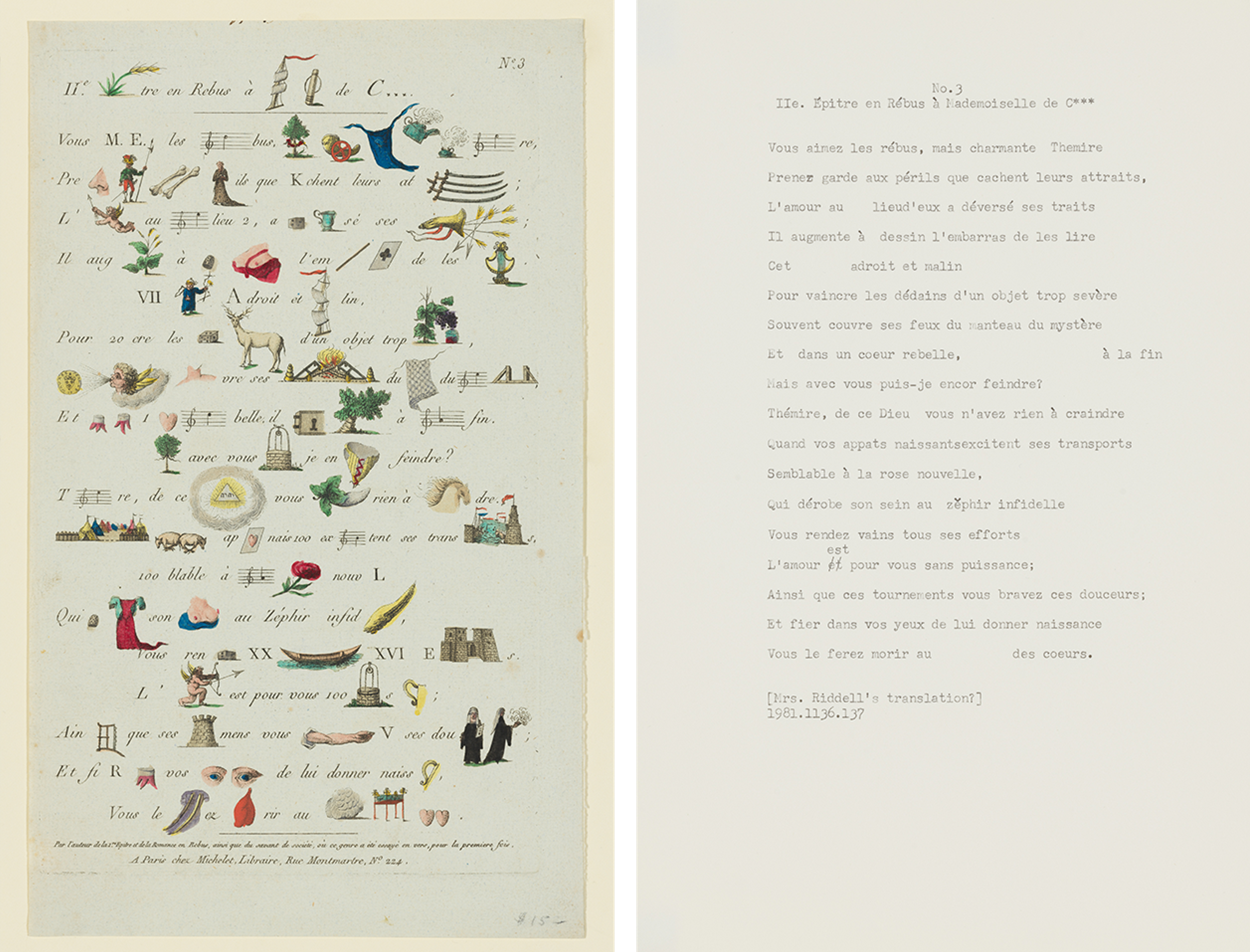

In a Michelet rebus of a later date, a different address is listed for the publisher, thus enabling contemporary viewers to trace its relocation within Paris. Addressed to an unidentified recipient, “Mademoiselle C***,” it contains beautiful hand-colored images of cupids and hearts. (Read a translation of the expression of love embedded in the rebus here).

Michelet Libraire (French). Rebus Valentine Letter, ca. 1840. Engraving with watercolor, 11 1/2 × 7 in. (29 × 17.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.137)

Later in the nineteenth century, rebuses began to appear on porcelain dishes and business signs, and in calling cards and children’s games. The genre continued to evolve into the twentieth century, with rebuses making appearances in advertisements and on television game shows. The rebus has long been a universal language!

I imagine that centuries ago, when rebuses frequently appeared in valentines, they offered a clandestine way for a shy sender to deliver a message of love politely, gently, and safely within the protocols of society. Hopefully the challenge did not overwhelm the recipient, who might have conceivably chosen another suitors’ elaborate lace missive with more easily understandable gestures of affection! Nevertheless, at that time in history, there were many beautiful options, and I hope that the recipients of these carefully crafted, challenging, and very trendy rebus letters enjoyed deciphering the endearing messages in a rewarding game of love.