The majority of the works on paper we treat in the Paper Conservation department consist of flat sheets of paper, which are usually displayed on gallery walls using window mats and frames. This is a tried and true, elegant solution for exhibition.

However, the world of works on paper is incredibly varied and artists are not known to be constrained by display considerations. This keeps things interesting for paper conservators! Sometimes we need to come up with solutions to exhibit drawings that are not intended to be shown in frames, but somehow need to be affixed to a wall: These can be oversized modern and contemporary works, works that are meant to form a shape (three dimensional or otherwise) that cannot conform to a frame with glazing, or other objects that are not intended to be presented with the aesthetic of a formal border that a mat and frame imparts.

Recently, three exhibitions at The Met displayed three very different works on paper in the form of scrolls rolled on both ends, each of which challenged the Paper Conservation department to come up with safe mounting methods to showcase these objects in visually exciting ways.

One of the show-stopping objects displayed in the exhibition The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England (2022) was the pair of enormous cartoons by Dirck Pietersz Crabeth (active 1539–1574) from the Gouda Sint Jan Foundation in the Netherlands. The sixteenth-century cartoons, depicting Philip II and Mary Tudor beside the Last Supper, are preparatory drawings for the King’s Window in the large Gothic Sint-Janskerk (Church of St. John) in Gouda, the Netherlands. Dirk Pietersz Crabath was a Dutch Renaissance glass painter, glazier, tapestry designer, and mapmaker. He and his brother Wouter Crabath I were employed by the Janskerk in the city of Gouda during the sixteenth century, where they created nineteen of the fifty-two stained glass windows for the Gouda Glass Project. These windows are one of the reasons that the church was placed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) list of monuments. The stained glass windows are remarkable for their ambitious scale and technical brilliance, and are extraordinary survivors of the Great Iconoclasms or Iconoclastic Furies of the sixteenth century (Beeldenstorm in Dutch) when outbreaks of destruction of religious imagery occurred across Europe.

Left: One cartoon being prepared for installation. Right: The final installation (without plexi bonnet) with conservator Yana Van Dyke

Displaying the cartoons vertically gives the visitor an accurate sense of the monumental scale of the glass project for the church (each nineteen-foot panel is only a fragment of the whole window). The cartoons served as functional design drawings for the stained glass work and were drawn and created in a 1:1 scale with the actual stained glass windows.

Scrolls were also displayed in Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition (2022) in a form that might be more familiar to viewers: rolls of wallpaper. Printed wallpapers were used extensively by the Cubist artists Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris. Loaned from the Musée du Papier Peint in Rixheim, France, the exhibition’s display of commercially available wallpapers used by these artists in their collages was important to visually explore their artistic practices. Some of the machine-printed wallpapers on view were identical to those used in Cubist collages, and were displayed as they would have been experienced by the artists as they selected their materials. Rolling and unrolling these wallpapers was quite a challenge, as the paper is vulnerable to tears, and perfectly even rolling was essential for an aesthetically pleasing and safe display.

Gallery view of the wallpaper scrolls. Wallpapers, Unidentified French Manufacturer, 1875–1925, Musée du Papier Peint, Rixheim, France, CTO.152. Rights and Reproduction: Courtesy of Musée du Papier Peint

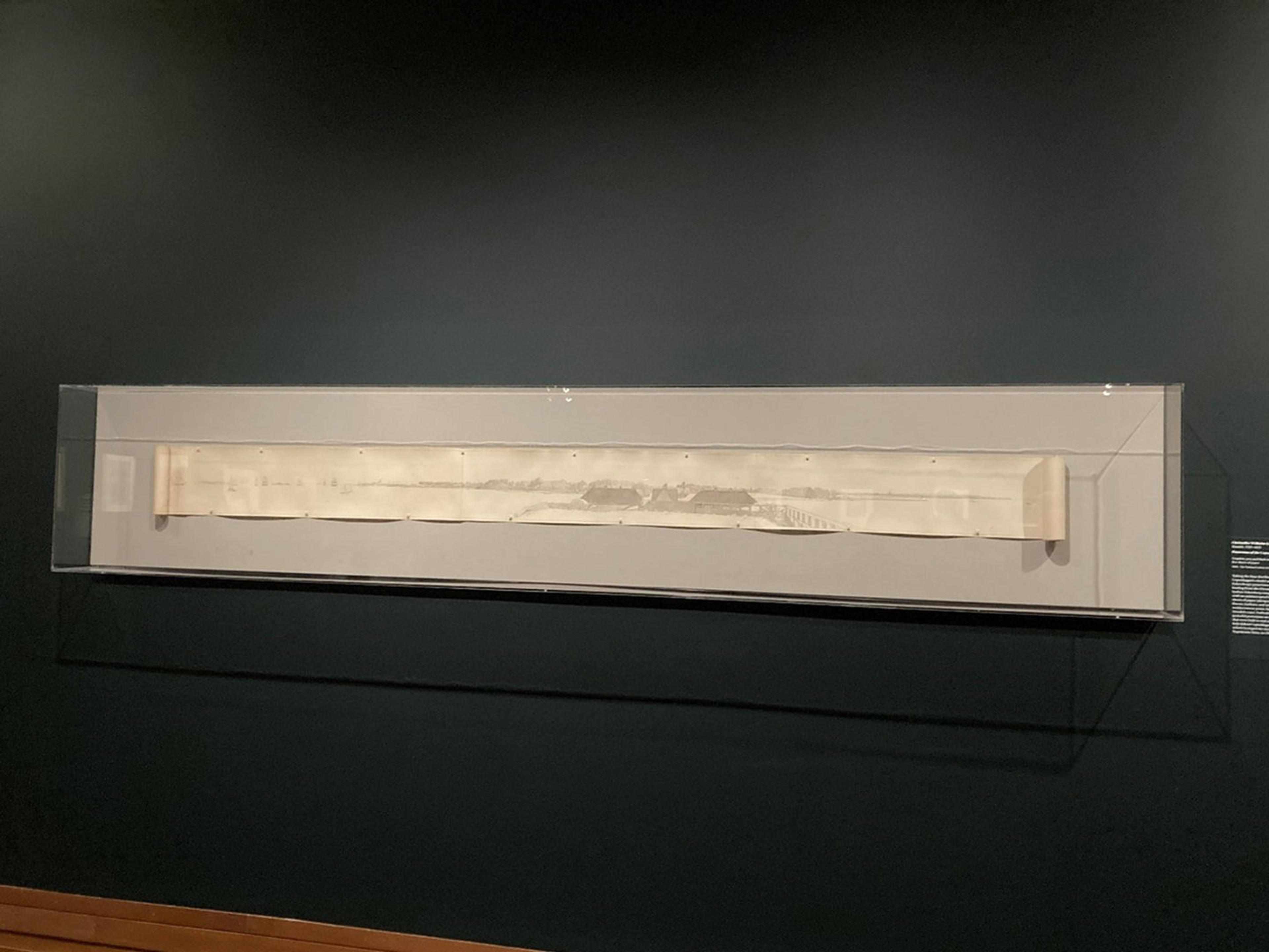

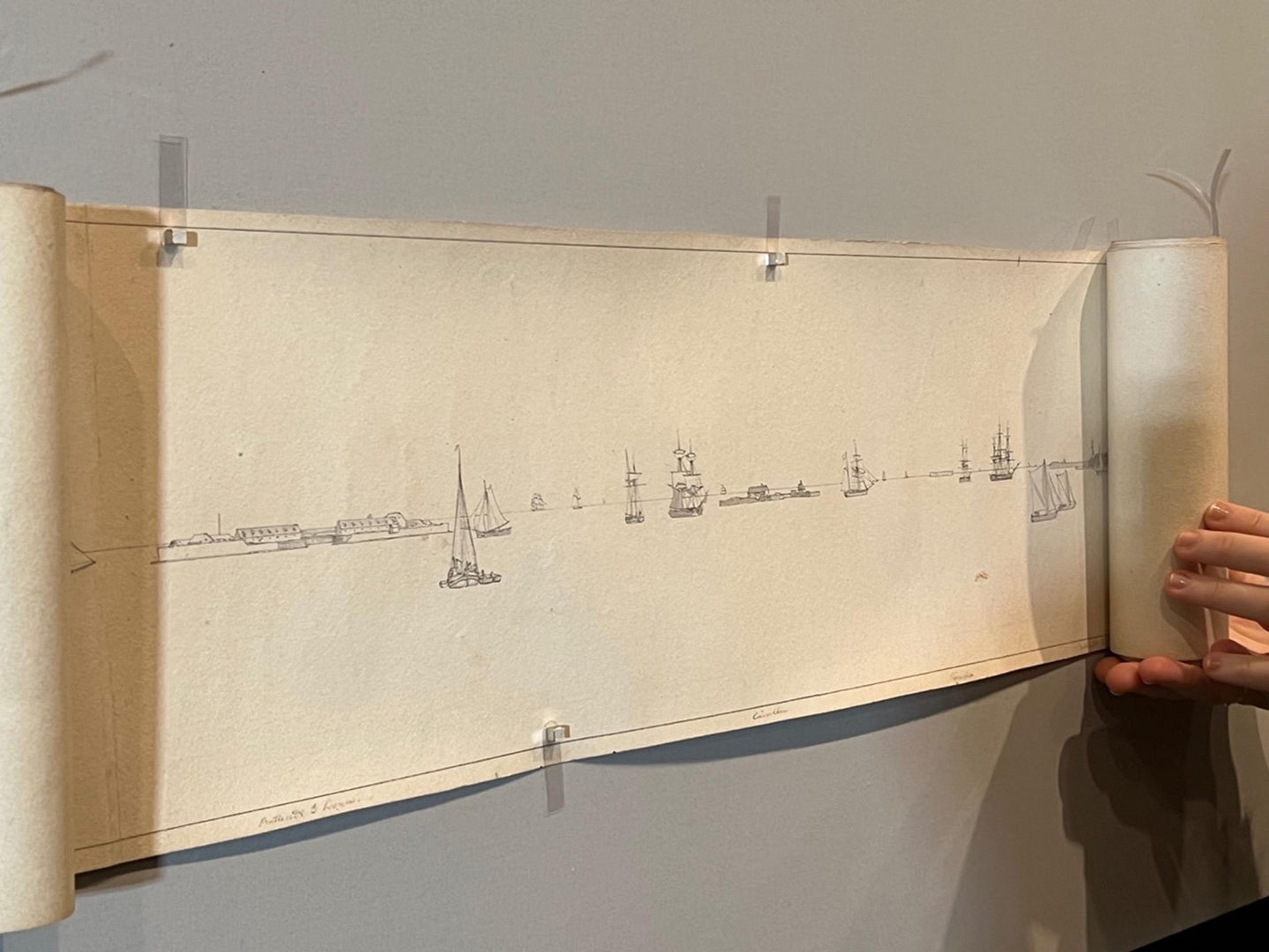

The last scroll of this recent group is a panorama shown in Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in Nineteenth-Century Danish Art (2023). This graphite drawing titled Panorama of the Copenhagen Roads (1828–39) by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg gives the viewer a picturesque journey as they walk along the 8.5-foot display of the scroll opened almost to its full length.

Final installation. Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, Panorama of the Copenhagen Roads, 1828–39, Graphite, pen and black ink, brush and gray wash, on five sheets of paper, Statens Museum for Kunst

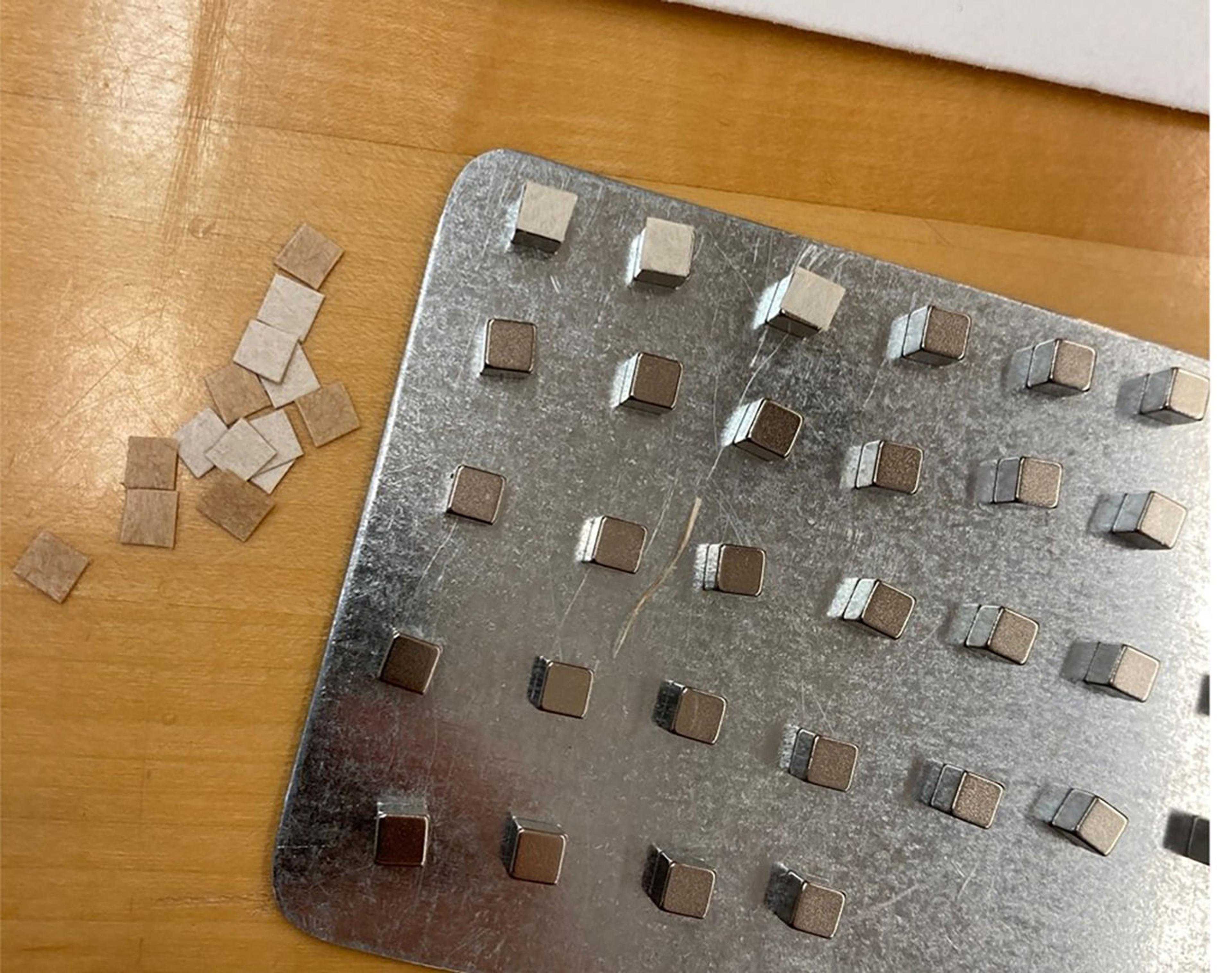

In order to display this long scrolled object safely and with minimum visual interruption of the sparse and delicate drawing media, we decided to use small “rare earth” magnets to affix the drawing to the back of a display case. The case was backed with a magnetic (iron-containing) sheet of metal and covered with a safe fabric approved for direct contact with organic objects.

Rare earth magnets are available in a wide array of sizes, shapes, and strengths, and it’s essential to find the right magnet for a display such as this one: One wants a magnet that is strong enough to hold up the object but not so strong that it might form a dent on the paper surface after three months of display or be difficult to detach from the backing. One wants the most minimal size possible, but not so small that it is difficult to handle when installing and de-installing. After a few months of testing on a mockup, we settled on the ideal magnets and covered what would be the outward-facing side with paper in order to visually blend in with the panorama.

Covering the rare earth magnets with Japanese paper

It’s not safe for rare earth magnets to be in direct contact with paper as they can cause staining, so the magnets were affixed over tiny tabs of mylar, which also makes them easier to remove for de-installation. The results were quite successful as the magnets are barely noticeable and the form of the drawing as a scroll could be maintained.

Installing the panorama by unrolling and placing magnets

For paper conservators, each object is unique and no solution fits all when it comes to exhibitions. There is also the added potential for surprises when we are dealing with objects loaned from another institution that we haven’t had a chance to handle. But all of our planning is rewarded when installation is finished, and viewers are able to enjoy these types of rarely seen objects on display.