With the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing reopening in May 2025, a team of conservators and scientists have been investigating a selection of West African dance crests that will soon be on display. Dance crests are worn on top of the head as part of full costumes, collectively referred to as masks, and danced at significant events. In the Cross River region of Nigeria and Cameroon, artists wrap their crests in carefully prepared and decorated animal skins, a practice that is unique to the region. The technique has been relatively understudied, but advanced imaging and technical analysis help reveal a history of complex, multilayered repairs. While some may view these repairs as distracting evidence of damage, they provide valuable information on how the piece was made, valued, and cared for throughout its history, from the first maker to its current home at The Met.

Headdress: Janus, 19th-20th century. Nigeria, Lower Cross Region, Ejagham or Bale peoples. Wood, untanned animal skin, pigment, cane, horn (Kobus kob), metal (iron alloys), bone or ivory, H. 20 1/2 × W. 18 5/8 × D. 13 1/4 in. (52.1 × 47.3 × 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.299)

Beneath the surface, each dance crest contains a carved wooden core, often human in form, like this striking two-faced crest. Fresh animal skin was stretched over the wood and secured with cords and nails to hold the shape while the skin dried and shrunk. The final rawhide is strong and durable, but can easily crack and fracture under pressure. Since these crests were worn and performed during major events, it’s not surprising that some damage could occur that would need repair.

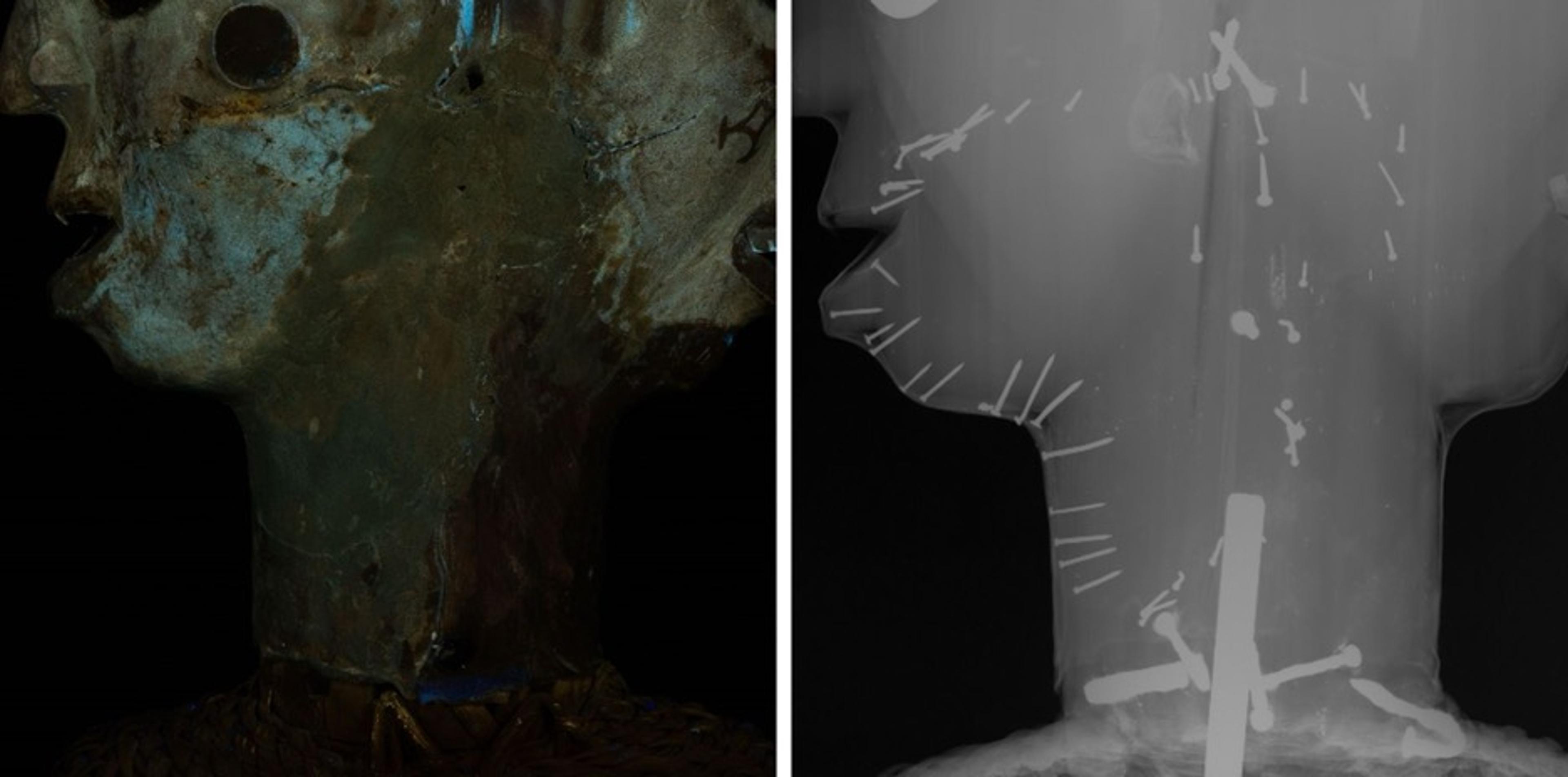

On this two-faced dance crest, the lighter area on the left cheek of one of the faces corresponds to a large repair. The repair was also made with animal skin, but ultraviolet imaging reveals that the repair was painted with a different pigment than the rest of the work. X-radiographic imaging also reveals small nails surrounding the repair, in contrast to the large iron nails that secure the original skin and decorative horns.

Left: Detail of Headdress: Janus under ultraviolet light, highlighting the repair on the cheek. Right: Detail of the X-radiographic image of the same area, highlighting the small nails around the outline of the repair, compared to the larger fabrication nails directly above and below it.

The behavior of the paint and the appearance of the nails suggest that this repair was added much later in the life of the piece and with different, though sympathetic, techniques. Whether this area was repaired by the community or by a later caretaker is difficult to determine, and multiple overlapping repairs are difficult to separate out. Further analysis of the coatings and paint binders in the two areas could provide clues.

Headdress: Ram, 19th-20th century. Nigeria, Lower Cross Region, Ejagham peoples. Wood, untanned animal skin, iron nails, cane, twine, cloth, metal (lead alloy), pigment, resins, H. 16 3/4 x W. 10 3/4 x D. 11 in. (42.5 x 27.3 x 27.9 cm.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1970 (1978.412.625)

A crocodile-like dance crest depicting the water spirit Nimm also bears a sympathetic but clearly visible repair at the top of the forehead. Animal skin was again used as the base material to fill the missing area, but here the difference in pigment application and tone is much more pronounced. Using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, Scientist Adriana Rizzo in The Met’s Department of Scientific Research identified that the original decoration consisted of layers of plant resin, which flaked severely as the resin aged. In contrast, the repair patch has an even, redder tone, and the skin may have been stained or toned rather than coated in resin.

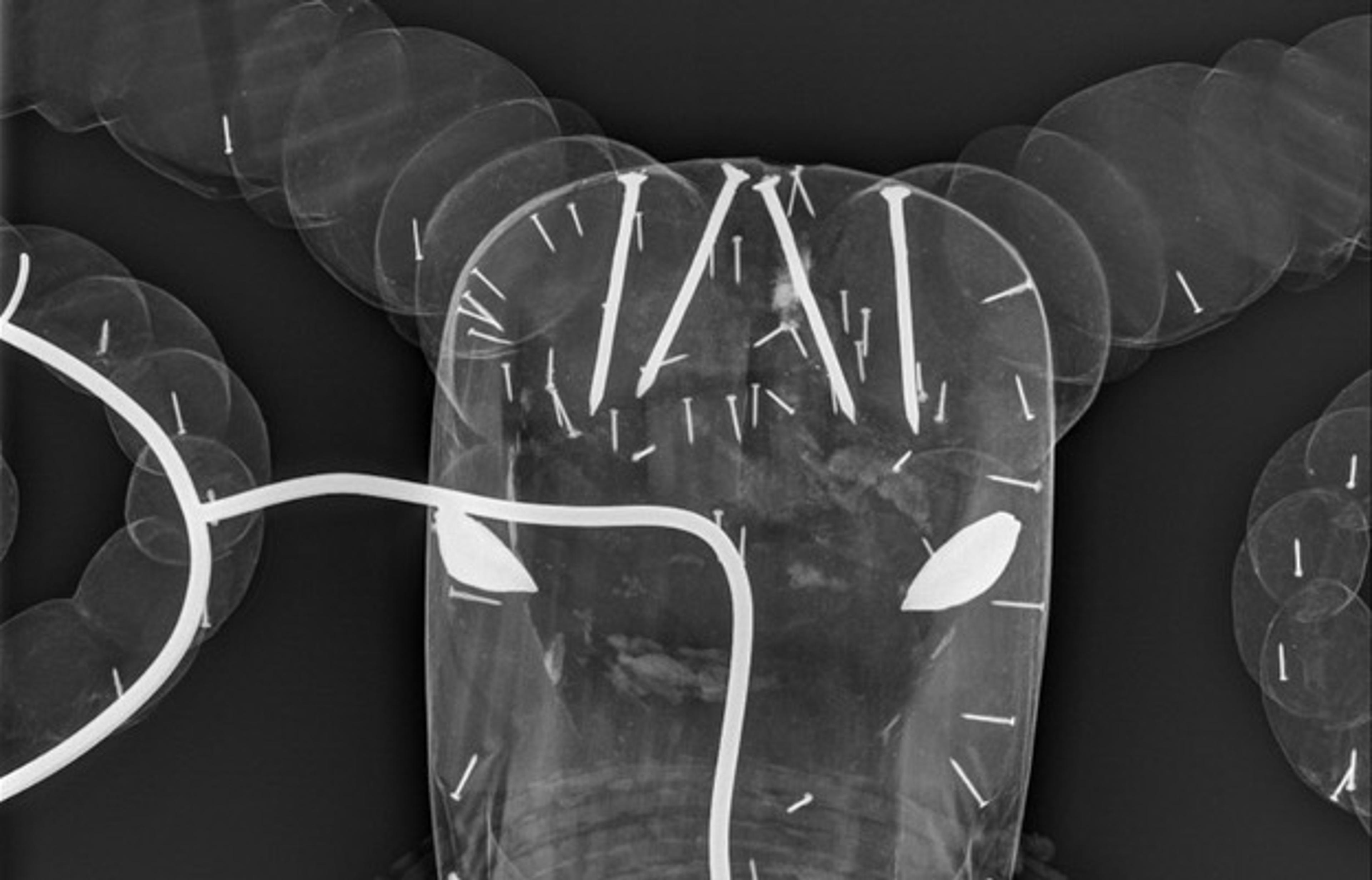

Detail of an X-radiographic image of Headdress: Ram, highlighting the near-identical nails across both the repair and the original seams.

Interestingly, unlike the two-faced dance crest, the same type of nail seems to have been used both in the repair area and along the seams where the skin is tacked down to the wooden core. This suggests that this repair may have been made during the crest’s use life.

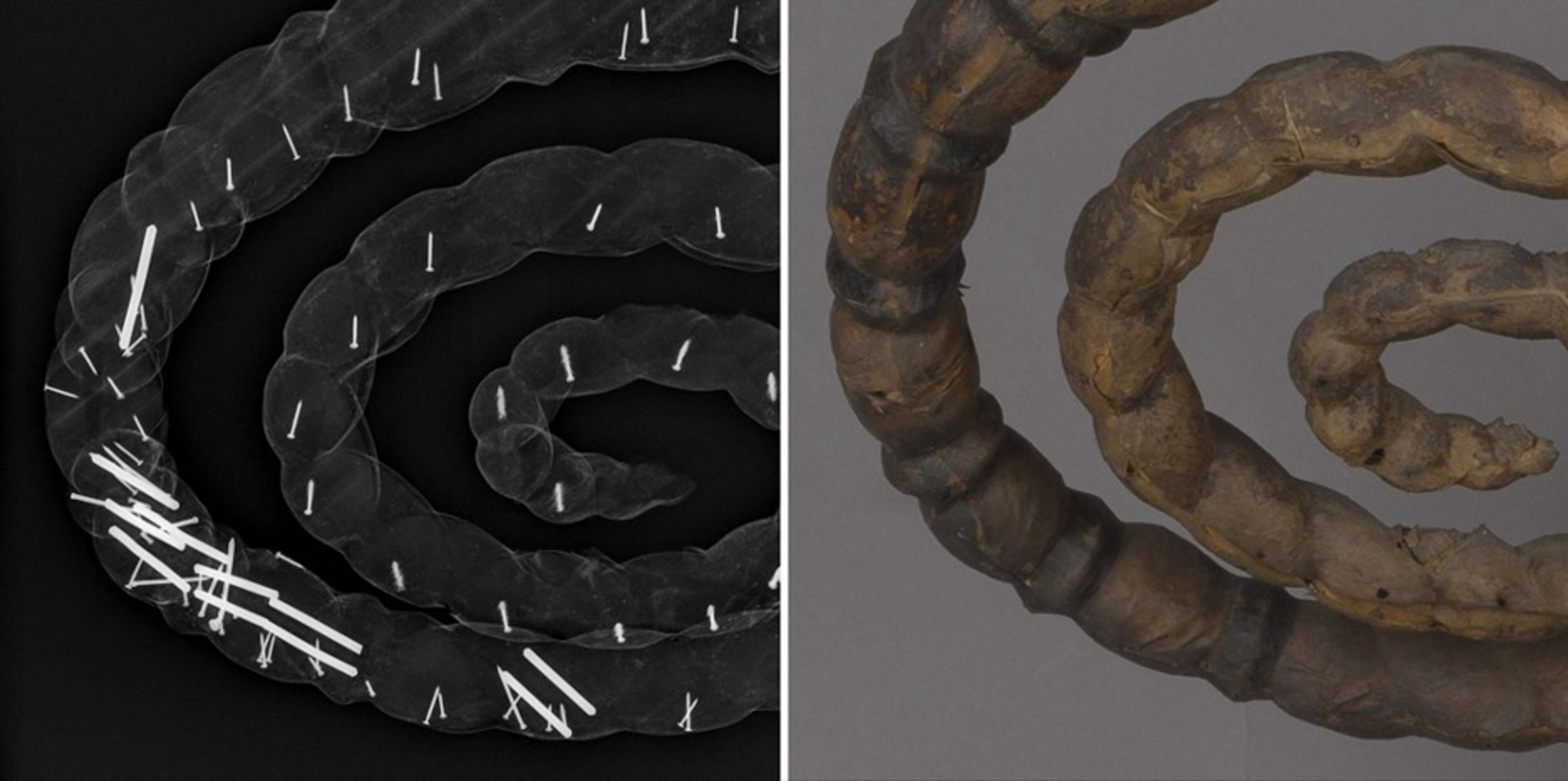

Radiography also reveals a hidden repair in the lower sections of the left-hand coil: pairs of metal rods intersect the wooden core, undetectable with the unaided eye. Perhaps the wood snapped during carving, or the coil snapped from the motions during performances, but extra support was clearly needed.

Left: Detail of an X-radiographic image of Headdress: Ram at the left coil, displaying the metal bars hidden inside the wood for support. Right: Detail of the same area on the backside of the coil, showing the seam in the animal skin and a number of the losses from previous nail holes.

Upon closer examination, the repair area was covered by a cohesive section of skin, with only one complete break around the outer arm of the coil. There is an extra hole on the back seam, adjacent to the nails, and more nails are visible in the X-rays of the area, suggesting multiple rounds of tacking. In order to perform such extensive repairs to the wood without damaging the skin, the section would need to have been completely removed and reapplied, which would have required risky rewetting and re-stretching of the skin. While there are subtle shifts in the texture of the skin and the resin layers in this area of the coil, the overall appearance of the repair is cohesive with the rest of the piece, implying that the person who performed the repair possessed intimate knowledge of the making process and likely was part of the local artist community.

The history of an artwork can be complex, with repairs that overlap and build upon one another. Some repairs are likely historic, such as the repair on the coil, while others appear to be later additions from an unknown hand. Often these past repairs have no records, and conservators must rely on analysis and observation to try to understand them. These further investigations help shine a light on the history of these objects and reveal the extent of care that was taken to preserve them.