When a loss on an artwork is noticeable to viewers, it always raises the question of reconstruction. Inpainting is the process of adding materials to fill areas of loss in an artwork to restore its overall look. It improves the legibility of an image, thus making it easier to understand and appreciate by viewers. In the conservation field, inpainting is typically not considered as a conservation treatment because it does not improve the condition of the object, and only operates on an aesthetic level.

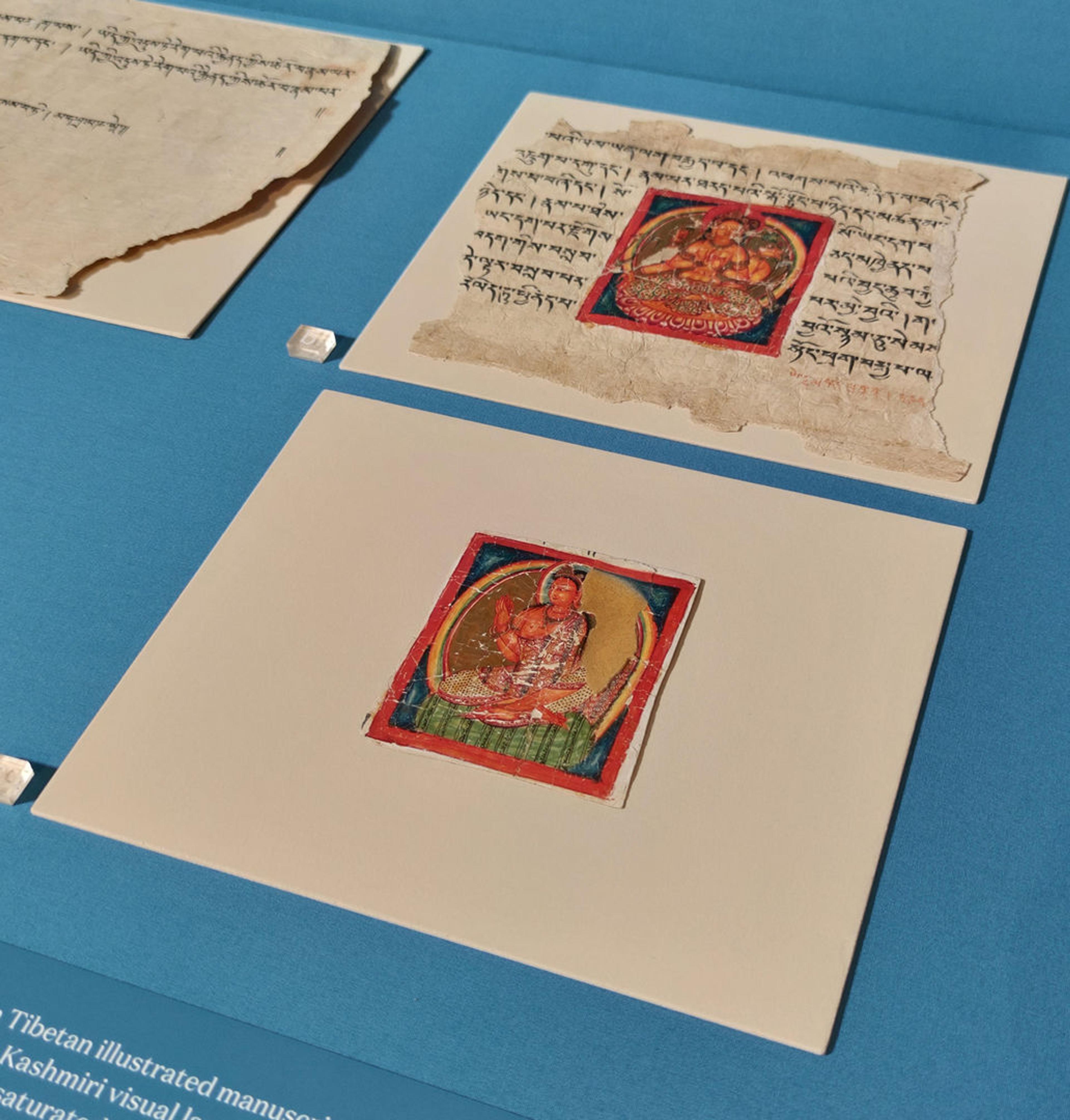

An object included in the exhibition Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet (on view in the Museum from September 19, 2024 to January 12, 2025) initiated discussions amongst curators and conservators from the Departments of Asian Art and Paper Conservation about the ethical considerations of inpainting on a specific artwork.

Fragmentary Leaf from an Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra, 12th century. Kashmir or western Tibet. Gold, opaque watercolor, and ink on paper, 3 3/8 x 3 in. (8.5 x 7.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Chino Franco Roncoroni, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2020 (2020.74.1)

The image above is a fragment from an Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra, dated from the twelfth century and produced in Kashmir or western Tibet. The miniature painting was cut from a sheet of paper which was most likely formed in a rectangular shape. This sheet of paper, or leaf, would have contained the sacred text of the Prajnaparamita, fundamental to the Mahayana doctrine of Buddhism. In this tradition, such leaves are read, recited, or simply commissioned to make merits.

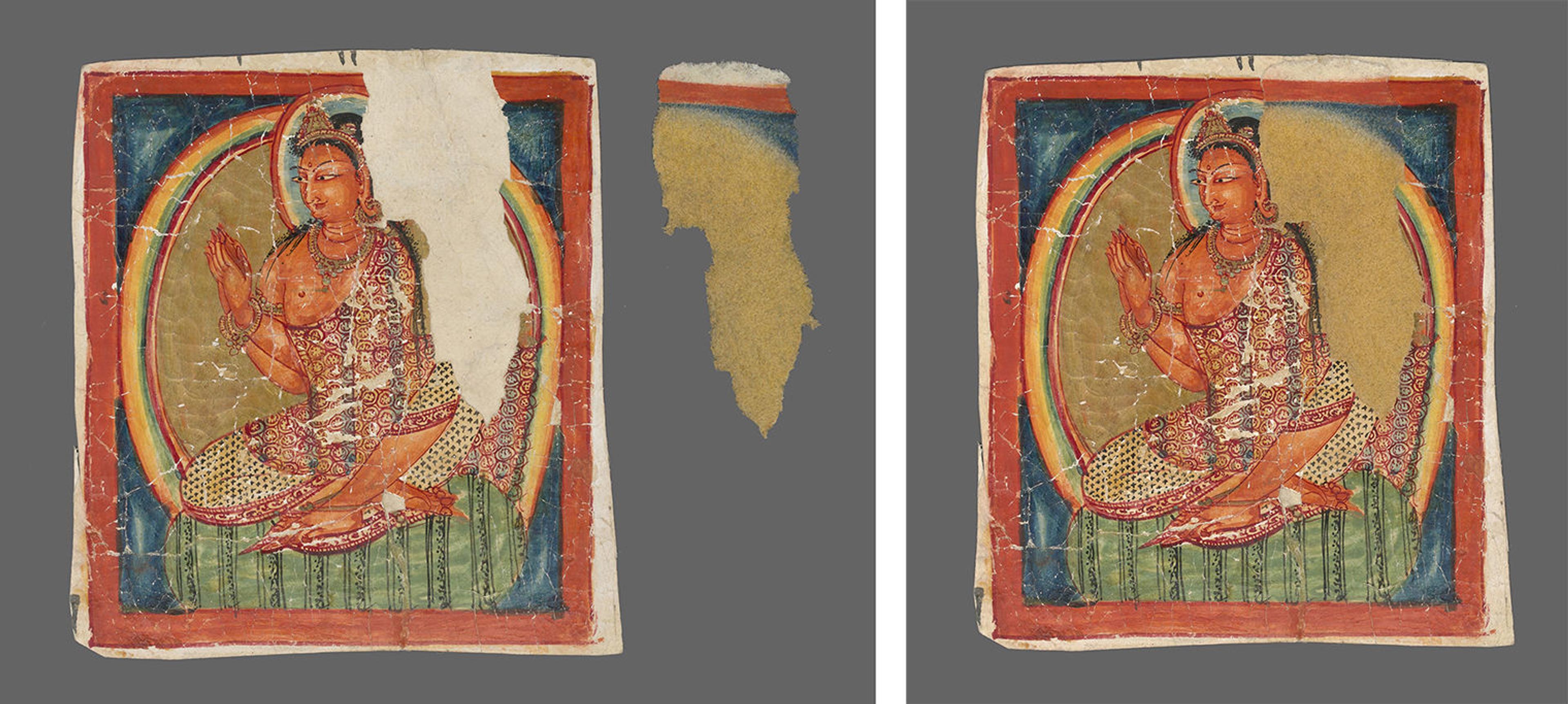

A very large area of loss in the top right section extends from the red border to the body of the figure. Likely caused by a tear, the outer layer of the paper was damaged and affected the image. After careful stabilization of the artwork to ensure its preservation, a thoughtful conversation occurred to evaluate the possibilities of improving the legibility of the image by inpainting the missing area while being considerate of its history and purpose. The cultural and historical context of this object, its sacred function, the ancient period of creation and its use were addressed, and digital reconstructions helped visualize the possibilities.

Multiple levels of inpainting of the missing area were considered, from neutral to the complete reintegration of the image.

Digital reconstruction: Neutral tone matching the tone of the paper support

The image above shows a first approach of compensation. It consists of a neutral tone that functions as a very noticeable inpainting.

Digital reconstruction: Colors matching the main shapes of the composition

A second proposal was created where the main shapes of the composition—the red border, the blue background and the gold halo around the figure—were integrated with colors corresponding to each element. This degree of inpainting facilitates the reading of the composition, while still allowing viewers to differentiate between original and inpainted parts.

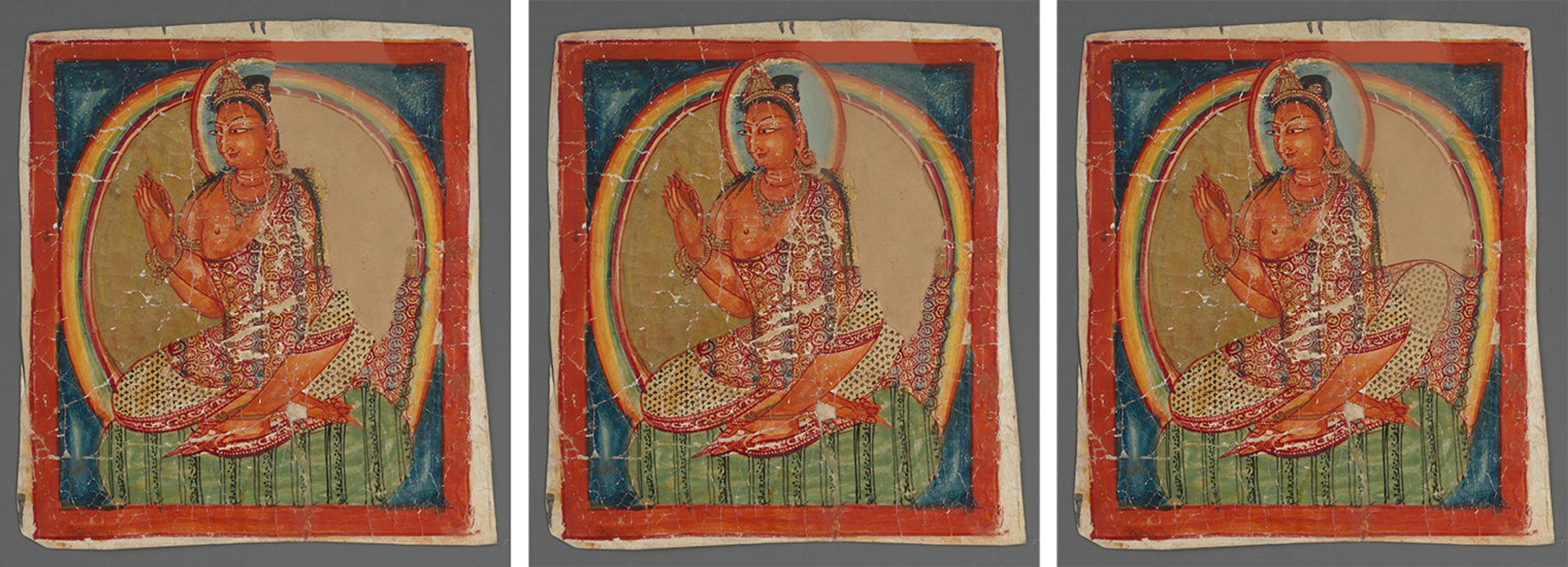

Digital reconstructions in three stages. Left: Reintegration of the rainbow. Center: Reintegration of the halo. Right: Reintegration of the missing knee

A third proposal, divided into three distinct stages, suggests the complete reintegration of missing areas: the rainbow, the blue halo around the figure’s head, and the missing knee of the figure. However, this option involved some invention since the exact details of the original image were unknown.

After shared conversations and careful considerations of all proposals, the last three proposals were deemed too interpretative of the work. It was determined by consensus that the inpainting was solely intended as an aid to help the viewer appreciate the painting without being distracted by the large white area of loss. The second proposal with neutral colors to suggest the shapes of the composition was chosen. In our opinion, it successfully conceals the area of loss while reading as an addition to the original work.

To achieve this inpainting, we created a paper sheet that was shaped to match the missing area.

It was carefully cast using traditional methods of papermaking. A paper with similar characteristics to the artwork was cut into pieces, soaked, and cooked at low temperature for several hours, mixed, filtered, cast to the desire shape, dried in a press, and sized with starch paste.

A toning process, adding color to the created paper, was also carried out by applying watercolors with an airbrush, supplemented by an application of watercolors with small brushes and pencils.

Left: The artwork with the inpainted paper on the right. Right: The inpainted paper resting on the artwork

It was decided to use the inpainted paper as a temporary visual aid for the duration of the exhibition. The paper rested on the artwork without the addition of any adhesive. Therefore, it does not interfere permanently with the artwork.

The artwork in its case with the inpainted paper resting on it. Also depicted above: Fragmentary Leaf from an Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra, 12th century. Gift of Chino Franco Roncoroni, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2020 (2020.74.2)

Inpainting can impact the perception of a work of art by viewers, and as such it is often subject of much consideration among museum professionals. For this artwork, historical and cultural significances guided the decision, ensuring that the inpainting helped viewers focus on the image without impacting the original material. This inpainting case highlights a fundamental principle of conservation: Interventions should be reversible, allowing future generations to remove previous approaches and re-evaluate the artwork with new perspectives, possibly reflecting different ethical standards. Reversibility ensures the possibility of different interpretations in the future, while still allowing today’s viewers to appreciate the artwork.