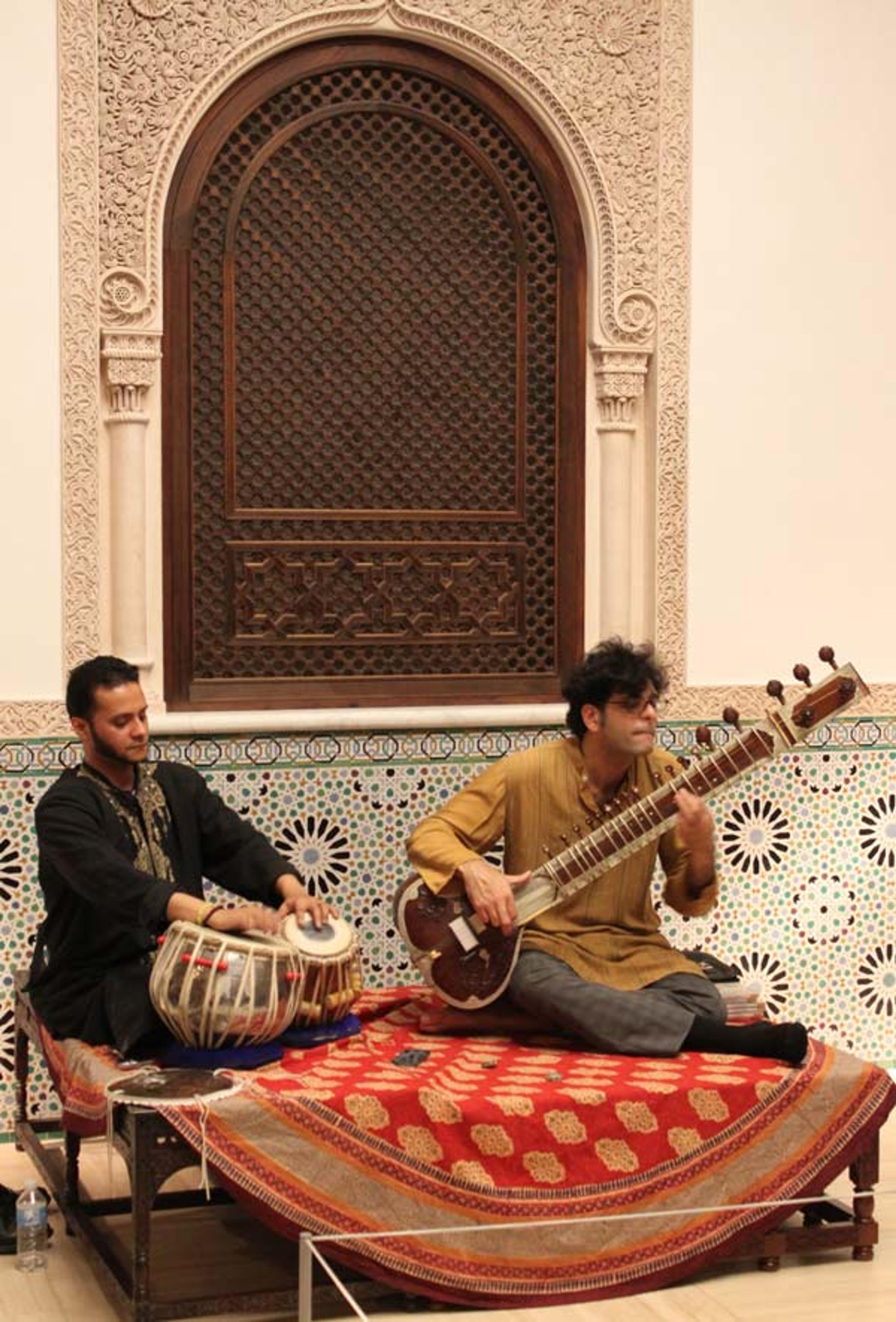

Neel Murgai opens the performance on the sitar. All photographs courtesy of the author

«The Moroccan Court Music Series, which began in April 2014, saw its last performance of the year on November 21, with a program of Hindustani music. Planned to coincide with the recently closed exhibition Treasures from India: Jewels from the Al-Thani Collection, the evening featured Neel Murgai on sitar and Shivalik Ghoshal on tabla, playing a program of north Indian ragas.»

Murgai and Ghoshal began by explaining that a raga is the melodic structure of a piece, forming the basis of its composition or a musician's improvisation. It consists of a set arrangement of ascending or descending notes (similar to a scale), with different points of stress given to each note. Murgai explained that the raga gives color to a piece and, in the north Indian tradition, actually corresponds to a certain time of day and year—some ragas are designated to be played in the morning for example, others in the evening.

The duo's first piece, lasting around forty-five minutes, exemplified many of these concepts. Murgai started with an alap, the opening section of a piece, on the sitar without rhythmic accompaniment. He later explained that this section sets the tone of the whole work and introduces the essential melodic qualities of the raga. The sitar, one of many instruments that can play a raga, is a type of lute derived from the smaller Persian lute, the setar. The sitar became popular during the Mughal Empire (1526–1858) and its modern-day construction consists of around thirty metal strings, a long neck, and a rotund body that sits on the musician's lap.

The sitar is often accompanied by the tabla, a two-headed drum that sets the meter or pulse of a raga. The larger, left-hand drum, the baya, produces the bass in a piece, while the smaller, right-hand drum, the daya, is narrower and higher in pitch. Although the tabla primarily sets the rhythmic structure of a piece, it is also rich in tonality and its range of strokes or bols are said to resemble a language. Syllable sounds, such as dha, dhin, and ka describe the way one hits the drum to produce a sound. Ghoshal noted that pronouncing these syllables is fundamental to learning the instrument: "If you can't say it, you can't play it." Using both hands enriches the sound and allows for a huge range of tonal possibilities.

Throughout the evening, I noticed that Ghoshal often tapped the sides of the daya with a hammer-like tool. He later explained that the instrument is very sensitive to temperature and requires frequent tuning. By tapping the woven leather stitching (gajara), even tension is maintained on the drumhead (pudi). The tuning of the daya depends on what scale is being played by the accompanying instrument.

Shivalik Ghoshal tunes the tabla

The descriptions of the instruments, which were interspersed with Ghoshal and Murgai's playing, were extremely useful. And I later found out that this format mirrors the pedagogical framework used when teaching Hindustani music. Its traditions are still largely taught by way of gurus (teachers), rather than books. Integral to this oral method of passing traditions from one generation to the next is the concept of gharana, meaning school. Ghoshal explained that the word translates literally as "coming (khar) home (ana)" and represents the place from which a musician hails and around which his practice is centered. Though the gharana's name reveals its geographic origin, the idea of gharana goes far beyond this. It encompasses the ideology and teaching philosophy established by the founding figure.

Gharanas are specific to each instrument and the tabla and sitar are generally considered to have six gharanas each. For tablas, for instance, the gharanas are Ajrara, Benares, Delhi, Farrukhabad, Lucknow, and Punjab. During the time of the Mughal Empire, it is said that each style had one master who would compete in the sultan's court once a year. The cash prize given to the declared winner would not only be a source of livelihood for his hometown, but would entitle him to "bragging rights" for that style until the following year's contest. The competitive culture surrounding these gharanas meant that compositions were kept secret and often given as dowries.

Nowadays, with the proliferation of music-sharing platforms like YouTube, it is common to share compositions and fuse styles, even if a musician primarily identifies with one school. Ghoshal, for instance, considers himself a hybrid of the Punjab and Lucknow gharanas, while Murgai hails from the Maihar school, one of the more popular, modern gharanas, played by notable figures such as Ravi Shankar.

While their music is still based on centuries-old teachings, Murgai and Ghoshal emphasized their need to stay fresh as contemporary musicians. They both play weekly in the Brooklyn Raga Massive, a collective that combines Indian classical music with an open jazz session. Improvising with other musicians keeps them sharp and is distinct from playing a formal concert. This collaborative energy was evident during the evening as Ghoshal and Murgai segued seamlessly between musical compositions and commentary, moments that seemed improvised, and ones that felt more structured.

Shivalik Ghoshal (left) and Neel Murgai (right) perform together

The Moroccan Court Music Series is made possible by the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art and The Persepolis Foundation. This year, performances in the series will take place on February 27, March 13, March 20, May 1, June 19, September 18, and November 13. For more details, please contact julia.rooney@metmuseum.org.