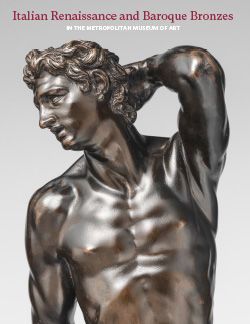

Mercury and Cupid

Francesco Fanelli Italian

Born and trained in Florence, Francesco Fanelli established his family workshop in Genoa (1605–30). His wide-ranging talents as a designer, marble carver, and bronze founder caught the attention of a youthful English court eager to elevate its prestige with lavish artistic commissions in the novel Baroque style. In 1632, at the height of his career, Fanelli settled in London and was awarded a pension from Charles I, who appointed him royal sculptor three years later.[1] During his eight years of service (1632–39), Fanelli worked on a variety of sculptural projects large and small for the king and important noble patrons. George Vertue credited the sculptor for popularizing the Italian art of the bronze statuette in England, noting that he “had a particular genius for these works,” which were, “sett on Tables cupboards [and] shelves by way of Ornament.”[2] The Met holds a number of diminutive collector’s cabinet statuettes, for which Fanelli is still best known, including the Adonis (cat. 94), Venus (p. 00, fig. 94a), Galloping Horse (cat. 95), and Cupid on Horseback.[3] However, no other bronze figure group attributed to Fanelli approaches the compositional complexity, sheer invention, artistic quality, and imposing dimensions of the Mercury and Cupid.

Here, Fanelli theatrically animated an episode from Apuleius’s bawdy ancient Roman novel, The Golden Ass.[4] Mercury is poised at the instant of flight, balancing one winged foot on a cloudbank and kicking outward with the other. As three puffy-cheeked wind gods gust Mercury skyward, a tiny infant Cupid squirming on the cloud, grabs at his legs desperately attempting to thwart the liftoff. The god of love’s comically ineffectual struggle merely earns Mercury’s amused backward glance. And with trumpet in hand, the messenger god inexorably rotates upward to make his fateful announcement: Cupid’s beautiful mortal lover Psyche must return to his jealous mother Venus. Although Apuleius’s novel of the star-crossed affair between Cupid and Psyche was popular in European Renaissance courts and the subject of major fresco cycles by Raphael (Villa Farnesina, Rome) and Giulio Romano (Palazzo Te, Mantua), it very rarely occurs in sculpture.

The Mercury and Cupid is a relatively recent discovery. When introduced at auction in 1985, the group was identified generically as “17th century.” In 1992, based on style and facture, Patricia Wengraf assigned the bronze to Fanelli and dated it to his English period. Its inclusion in internationally important scholarly exhibitions has secured general acceptance of Wengraf’s attribution.[5] Claudia Quentin acquired the group shortly after seeing it in the landmark show Von allen Seiten schön of 1995. It was the first important bronze that she purchased, and the work’s rarity, quality, and sensuous beauty are the touchstones that inspired her decades-long acquisition of statuettes that today form a renowned collection.[6] In 2021, The Quentin Foundation generously gifted the work to The Met. Only two other casts of the Mercury and Cupid are extant. One is a nineteenth-century bronze in the Hermitage.[7] The other, a Mercury lacking the Cupid and base (present location unknown), was formerly in the collection of Edgard Stern, Paris, and restituted in 1946 to Edgard’s wife Marguerite Fould.[8]

Exceptionally well preserved, the Mercury and Cupid has survived intact, retaining all of its original elements and most of its lustrous black surface patina. The figure group was cast in sections using the lost-wax method.[9] Upon close inspection, casting flaws and repairs are visible, for example, at the joins connecting Mercury’s legs to the torso and the upper arms to the shoulders. The original black patina applied over the bright brass-colored metal was intended to hide these indications of facture. The combination of yellowish base metal with obscuring black varnish, or paint, is characteristic of the bronzes Fanelli created while he served at the court of Charles I. Abraham van de Doort’s 1639 inventory of the king’s goods, for example, records one of Fanelli’s five statuettes in the royal collection as having been made “in brasse beeing wth vernish blackt over . . .”[10] As is typical of Fanelli’s English sculptures, the Mercury and Cupid is minimally tooled in the metal. The smooth silken forms of the nude figures, clouds, and winds, as well as sharply incised details such as the feathered wings, were highly finished in the wax and directly cast in the bronze.

The bronze’s ambitious size and sweeping forms closely relate to Fanelli’s large-scale sculptures. His designs of around 1639 for the statues ornamenting fountains in the Varie architetture, for example, share the same figure types, dynamic rotational energy, and elegant wit sublimely expressed in the Mercury and Cupid.[11] The distinctive wavelike crest on Mercury’s ornate helmet occurs again ridging the armored shoulder pieces (pauldrons) on Fanelli’s bronze bust of Charles I (ca. 1635–40).[12] The Mercury and Cupid also shares formal elements with Fanelli’s small-scale statuettes. Cupid’s round, squinting features are characteristic of Fanelli’s lively putti. Mercury’s heavy eyelids and pouty mouth recall those of the David and Goliath (cat. 93) and the Adonis.[13] A version of the messenger god’s masked helmet occurs on the numerous extant casts of Saint George and the Dragon. Fanelli likely reused his design for the face ornamenting the original wood base of one of these statuettes for the three wind gods embellishing the Mercury and Cupid.[14]

Van de Doort’s inventory records a small “strugling mercurie standing upon one legg without streatched [with outstretched] armes like as if he were ready to fly . . .”[15] Wengraf associates this work with two bronze versions that are similar in subject but, according to the inventory dimensions, significantly smaller in size than The Met group.[16] Two wax models of the small versions also survive.[17] Significantly, near in height to these small examples is The Met’s David and Goliath, which is a late cast of a lost Fanelli bronze recorded in the king’s collection. Both royal cabinet sculptures expressed the king’s preference for complex, elegantly rotating figure groups that are pleasing when viewed in the round. Because the large size of the Mercury and Cupid precludes its function as a cabinet sculpture, one must consider other possible contexts for which Fanelli might have made it.

The group’s remarkable state of preservation indicates that it was always displayed indoors. The grand spiraling composition, exciting in sensuously luminous silhouette from every point of view, signals that Fanelli designed the Mercury and Cupid to be appreciated by viewers walking around it. These characteristics suggest it was intended for display in a large, imposing interior. It would have made an arresting centerpiece in one of the picture galleries that were coming into vogue at the Caroline court. The Mercury and Cupid might be related to a series of paintings depicting episodes from Apuleius’s Golden Ass that Charles I commissioned for the Queen’s House at Greenwich in 1630. Cupid and Psyche by Charles’s court painter, Anthony van Dyck, is the only picture associated with the uncompleted series (fig. 92a).18 The resonance between Van Dyck’s Cupid and Fanelli’s Mercury is striking. Each artist memorably captures a divine winged, windblown youth with arms outstretched, poised on one foot at the liminal instants of landing and flight. In Genoa, Fanelli frequently collaborated with painters, and it is tempting to consider how he might have done so in England. Van Dyck and Fanelli’s vibrant treatment of their Apuleian subjects hints at a possible interchange between Charles I’s premier sculptor and painter that contributed to the poetically charged artistic style developed over a brief decade (1630–41) during the king’s reign.

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. For Fanelli’s career in England, see Wengraf 2004; Stock 2004.

2. Vertue 1934, p. 110.

3. MMA, 1975.1.1400, modeled before 1639.

4. As cited in Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf 2004, pp. 202, 203 n. 25, the subject of Mercury and Cupid was first identified by Vertova 1993, pp. 52, 62.

5. Penny 2004, p. 846. For the exhibitions, see Krahn 1995; Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf 2004. 6. Verbal communication from Mrs. Quentin.

7. Inv. 1187, H. 78 cm (Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf 2004, p. 194).

8. Deutsches Historisches Museum, Datenbank zum “Central Collecting Point München,” no. 11493, at https://www.dhm.de/datenbank/ccp/dhm_ccp.php?seite=6&is_fulltext=true&fulltext=merkur+bronze&suchen=Quick+search&modus=exakt.

9. The sculpture was produced from at least fifteen sections that were joined mechanically, by casting some sections on, or with soft solder. Radiographs show extensive porosity throughout, which was repaired with poured metal patches and numerous, carefully fitted threaded plugs that vary from a few mm to over 1 cm in diameter. L. Borsch, February 11, 2021.

10. Millar 1960, p. 93, item 14.

11. Wengraf 2004, pp. 36, 39.

12. V&A, A.3-1999. I should like to thank Simon Stock for this observation.

13. Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf 2004, pp. 199–200, 202.

14. Sotheby’s, New York, June 1, 1991, lot 100; cited in ibid., pp. 202, 203 n. 23.

15. Millar 1960, p. 93, item 14.

16. Galleria Giorgio Franchetti, Ca’ d’Oro, Venice, CGF Br.255, H. 42 cm; Mercury, lacking the Cupid or base, formerly with Sotheby’s, London, April 22, 1993, lot 54, H. 34.5 cm; see Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf 2004, p. 194.

17. Lankheit 1982, p. 156, no. 10, fig. 239.

18. Lucy Whitaker in C. Lloyd 1998, pp. 34–35, cat. 2.

19. The “Stern Collection, Frankfurt” provenance of a bronze Mercury and Cupid published in Lankheit 1982, p. 156, no. 10, was incorrectly associated by the cataloguer of the 1985 Sotheby’s auction with The Met version and subsequently also in Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf 2004, p. 194.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.