Stirrup Spout Bottle with Seated Figure

Not on view

This ceramic stirrup-spout bottle in the shape of a seated man wearing a checkerboard tunic was created by potters of the Moche culture of Peru’s North Coast. The figure’s hair is enveloped in a tight fitting head wrap that extends down his back, with locks of hair extending down in front of each ear. Over his left shoulder he carries a small bag of the type used to carry coca leaves, decorated with horizontal stripes and a fringe at the bottom (see Donnan and Donnan 1997:227, fig. 29 and 233, fig. 42 for related imagery). Traces of black circular tattoos or paint adorn his cheeks, and he sports a moustache and a small beard. There are holes in his ear lobes for ear ornaments. His eyes are open, indicating that, unlike other figures in a seated position, he is not sleeping (see accession number 64.228.33 in the Met’s collection for an example of a sleeping figure). His arms are crossed under his tunic, perhaps for warmth, or perhaps as a gesture of unknown significance. Checkerboard tunics are closely associated with elite warriors (for an example and discussion see accession number 2017.674 in the Met’s collection). In other examples of Moche bottles featuring figures with checkerboard tunics the figure appears to be holding up the tunic, perhaps in a gesture of display (Pillsbury 2002:fig. 3).

The stirrup-spout vessel—the shape of the spout recalls the stirrup on a horse's saddle—was a much favored form on Peru's northern coast for about 2,500 years. Although the importance and symbolism of this distinctive shape is still puzzling to scholars, the double-branch/single-spout configuration may have prevented evaporation of liquids, and/or that it provided a convenient handle. The double-branch may have also held symbolic importance, reflecting a belief in the importance of tinku, a Quechua term for convergence, such as the confluence of two rivers. Early in the first millennium A.D., the Moche elaborated stirrup-spout bottles into sculptural shapes depicting a wide range of subjects, including human figures, animals, and plants worked with a great deal of naturalism. About 500 years later, bottle chambers became predominantly globular, providing large surfaces for painting complex, often multi-figure scenes.

The Moche (also known as the Mochicas) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from 200–850 A.D., centuries before the rise of the Incas. Over the course of some six centuries, the Moche built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River Valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although the precise nature of Moche political organization is a subject of debate, these centers shared unifying cultural traits such as religious practices (Donnan, 2010).

Published references

Wassermann-San Blás, Bruno John. Céramicas del antiguo Perú de la colección Wassermann-San Blás (Buenos Aires: Bruno John Wassermann-San Blás, 1938), p. 219. no. 386.

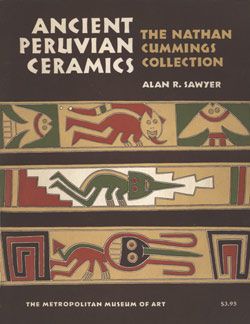

Sawyer, Alan. Ancient Peruvian Ceramics: The Nathan Cummings Collection (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1966), p. 26. no. 23.

References and additional reading

Donnan, Christopher B. “Moche State Religion,” in New Perspectives on Moche Political Organization, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Luis Jaime Castillo (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010), pp. 47-69.

Donnan, Christopher B. and Donna McClelland. Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists (Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles; Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1999).

Donnan, Christopher B., and Sharon G. Donnan, “Moche Textiles from Pacatnamu,” in The Pacatnamu Papers, vol. 2, The Moche Occupation, edited by Christopher B. Donnan and Guillermo A. Cock (Los Angeles: The Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles), pp. 215-242.

Golte, Jürgen. Moche cosmología y sociedad (Lima and Cusco: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos-Centro Bartolomé de Las Casas, 2009).

Mujica Barreda, Elías, et al., El Brujo: Huaca Cao, Centro Ceremonial Moche en el Valle de Chicama (Lima: Fundación Wiese, 2007).

Pillsbury, Joanne. “Inka Unku: Strategy and Design in Colonial Peru,” Cleveland Studies in the History of Art 7 (2002):68-103.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, editors. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017).

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.