Inkstand

After a model by Andrea Cinelli Italian

Not on view

By the mid-nineteenth century, this bronze inkstand had garnered a certain renown in England, where it was considered a superlative example of sixteenth-century decorative art and mentioned in the same breath as the famous inkwell from which Petrarch composed verses to his beloved Laura.[1] It was presented in the display of works of ancient and medieval art held at the House of the Society of Arts in London in 1850, and subsequently illustrated in summaries of the show in The Illustrated London News and The Art-Journal (fig. 172a). It was then included in the important Art Treasures of Great Britain exhibition, held in Manchester in 1857, and reproduced in its catalogue.

During this period, the inkstand was owned by the celebrated British industrial engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel. His brother-in-law recalled Brunel’s avid collecting of objects for his Duke Street residence: “well do I remember our visits in search of rare furniture, china, bronzes, &c., with which he filled it, till it became one of the most remarkable and attractive houses in London.”[2] The inkstand may have been acquired during Brunel’s trip to Italy in 1842. It was described in the 1860 sale catalogue of his collection as “a fine cinque-cento bronze inkstand, of triangular form, chased with arabesques and dolphins, and surmounted by a figure.” As an engineer, Brunel himself designed inkstands, so his interest in Renaissance utilitarian objects and bronze casting is not surprising.[3]

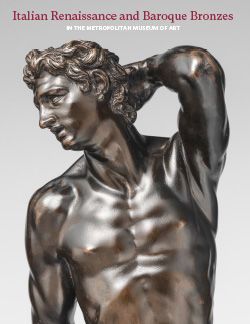

But is the inkstand truly a sixteenth-century production? When the work entered The Met in 1941, it was considered a product of Riccio’s workshop. It has since gone unpublished, in contrast to its mid-nineteenth-century ubiquity. The bronze is composed of multiple elements. A triangular base rests on masked satyr’s heads, each side featuring a relief of a siren figure and foliate ornament. The base contains three triangular compartments, each with a separate lid. Inserted between the compartments is the inkwell: a basin standing on three clawed feet and decorated with eagles. While much of the visual vocabulary indeed derives from the Paduan workshop of Riccio and his successors, certain elements—the finials, eagle’s heads, and masked feet of the base—seem indebted to a later sensibility.[4] The smooth, thick interior walls also point to a post-Renaissance manufacture.

Based on new research, the bronze can now be attributed and dated with more precision. It is neither the creation of a cinquecento atelier nor a nineteenth-century pastiche, but is instead modeled after a silver inkstand designed by the little-known silversmith Andrea Cinelli, active in the Vatican and Perugia in the mid-eighteenth century. Two silver inkstands of the same design have recently surfaced on the art market, in 2011 and 2018, and the markings of the first of these were identified as that of the Chamber of Commerce of Perugia (in use 1737–47), and Cinelli’s own maker’s mark (fig. 172b).[5] Either of these inkstands may be identical with one auctioned in 1985 at Sotheby’s Geneva and described as “probably Italian, mid-19th Century, in late 16th century Paduan style.”[6]

In photographs, all three silver versions that have come to auction retain the original cover element: a column surrounded by three seated putti holding up a garland. Since at least the mid-nineteenth century, as seen in illustrations, our inkstand’s lid has featured a single seated putto and is obviously of different manufacture.[7] This element was likely added at the time to appeal to collectors such as Brunel looking for Renaissance objects. The translation of a model meant for silver into bronze—perhaps done by taking a mold of the silver—accounts for the liquidity of some of the bronze’s modeling and the smoothness of much of its surface, internal and external. The eighteenth-century dating accounts for the eclectic design: one eye looking back to Padua and the ornament and grotesquerie omnipresent in Riccio’s work, the other eye fixed on the future, anticipating the nineteenth-century taste for the Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Gothic.

-JF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Manchester 1857, p. 218.

2. Brunel 1870, p. 507.

3. The Brunel archives at the University of Bristol include, for example, an 1836 sketchbook page of designs for an inkstand; one biographer recalls leafing through Brunel’s sketchbooks and finding “seven detailed drawings for an inkstand.” Morris 2015, n.p.

4. I am grateful to Jeremy Warren for his insights regarding the visual characteristics of the inkstand and its possible nineteenth-century origin.

5. Meeting Art, Vercelli, Asta 731, November 1–13, 2011, lot 697; Catawiki auction (online), 2018, lot 15550299. For the marks, see Donaver and Dabbene 2000, pp. 263, 266, refs. 2201 and 2227.

6. Sotheby’s, Geneva, November 12–14, 1985, lot 64.

7. More recently, the inkstand has been shown without this element.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.