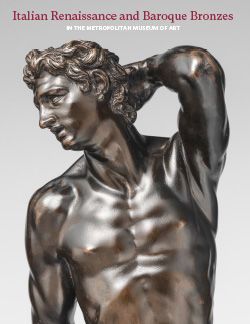

Horse and rider

Not on view

The most illustrious feature of this well-wrought, perky little group may be its “royal” provenance, from the Sun King, Louis XIV, to the so-called King of Tenors, Enrico Caruso. Rider and mount were cast separately and subsequently affixed by means of a metal tube fitted into the rider’s body, screwed into the mount’s belly, and soldered firmly in place.[1] The tail was also cast separately and inserted mechanically.

Wilhelm von Bode aptly captured the “momentary gestures” that describe the group’s “transitory states” and was right to think of it as belonging to the mid-sixteenth century, even if connections he clarified with Leone Leoni and monumental equestrian traditions remain invisible. Motivated by the endearing flow of its design, I was no more successful in associating it with the master of plaquettes known as Moderno, who was not known otherwise as a sculptor.[2] In reality, the bronze is hard to place. The bareback horse owes its sturdy charms, including its delicate topknot, to the famous ancient ones at the Basilica of San Marco in Venice, while the tightly knit commander is generically Roman, lacking insignia that might identify him as an historic leader. The fluidity of modeling in the masks on his breastplate and leggings is to be noted. The hole in his raised, clenched fist is oriented horizontally outward at a 45-degree angle, making it difficult to guess what action it might have performed. The hands could have held reins, but there is no bit in the horse’s mouth.

A similar statuette, differing in that it bears traces of gilding, a late black patination, and an obvious patch of repair on the steed’s right buttock, belonged to the earls of Rosebery at Mentmore, Buckinghamshire.[3] An example of the commander alone, with traces of gilding, also exists.[4]

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. The alloys of both horse and rider are a surprisingly high-zinc brass. R. Stone/TR, November 14, 2020.

2. For Moderno, now generally recognized as the Veronese goldsmith Galeazzo Mondella, see Lewis 1989. An old photograph of our bronze (Bode 1910, vol. 1, pl. LXVI) shows a pedestal embellished with a Moderno combat scene, but that alone does not warrant ascribing it to him.

3. Sotheby’s, London, March 18, 1977, lot 322 (as Paduan, 16th century).

4. Hôtel Drouot, Paris, June 18, 1997, lot 135 (as Paduan, first quarter of the 16th century).

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.