Medieval Globalism: Fragments of Chinese Ceramics in Nishapur, Iran

«Despite their meager size, ceramic sherds can provide valuable information about a historic site's economic and trading patterns. This is especially true of the sherds found at Nishapur, a site in northeastern Iran that flourished from the eighth to the 15th century.»

Left: Fragment of an imported Chinese ewer, 9th century. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Stoneware; molded and glazed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (40.170.455a,b)

The Mongol destruction of Nishapur in the 13th century and multiple earthquakes resulted in the city's relocation further to the west. Excavations conducted in the 20th century, including those carried out by The Metropolitan Museum of Art between 1937 and 1947–48, have focused on the site's more eastern areas and have yielded many ceramic fragments. A large number of these sherds are in The Met collection, while others are in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran.

As an intern in The Met's Department of Islamic Art for the past eight months, I catalogued, measured, and photographed unaccessioned Nishapur ceramic sherds in the Museum's storeroom. This prepared the objects to be registered and accessioned to the permanent collection, making them accessible to scholars and the public.

In my time at The Met, I diligently studied 250 ceramic sherds. Among these I was surprised to find five distinctly Chinese ceramics.[1] Represented among these pieces were fragments of various colors, shapes, and textures, including wares such as Changsha, Qingbai, Sancai, green-splash, Yue, and Ding. The newly catalogued pieces include a fragment of a Changsha bowl with an image of a bird, two lustrous white-porcelain fragments, a Qingbai ware with a lotus-petal pattern incised on the exterior, a partial base of a Jingdezhen ware with an incised motif on the interior, and one piece that belongs to a later period, a Ming-dynasty blue-and-white ware.

The uncovering of these additional five pieces coincided fortuitously with the exhibition Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia (March 7–June 4, 2017) at the Asia Society. At least seven Chinese sherds found at Nishapur correspond directly to the objects recovered in this ninth-century shipwreck. First discovered in 1999 near Sumatra, Indonesia, the "Belitung Shipwreck" contained thousands of Chinese ceramics and precious gold and silver vessels, many of which were miraculously preserved in near-pristine condition. The value that Chinese ware held in Western Asia is well attested, and scholars have argued that the shipwreck was bound for the Persian Gulf and that some of the objects on the ship were made specifically for export. This connection with China can be seen in many sites near the Persian Gulf in southern Iran and Iraq in the ninth and 10th centuries; however, witnessing a varied assemblage of Chinese wares at a site like Nishapur, which is inland and more than 1200 kilometers from the sea, is quite mind-boggling.

Changsha Wares

About 55,000 pieces of Changsha ware were recovered from the Belitung Shipwreck. These included beautifully painted bowls in green and brown with images of birds or clouds, or Chinese writing.

Left: Bowl with bird, 9th century. China. Stoneware painted with green and brown under glaze (Changsha ware). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dianne and Oscar Schafer, 1986 (1986.97.3). Center: Bowl with birds, ca. 825–50. China, probably Changsha kilns. Glaze stoneware with underglaze iron-brown and copper-green pigments. Asian Civilization Museum, Singapore (2005.1.00296). Right:Newly catalogued Changsha shard, 9th century. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Stoneware; painted under glaze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund

The Met has several pieces of such ware in the Chinese galleries, including bowl with a bird (above left). The shape and style of this bowl directly corresponds to a bowl with birds from the Belitung shipwreck at the Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore (above center). I was excited to discover and catalogue a piece of Changsha ware found at Nishapur, which is similarly decorated with an image of a bird (above right).

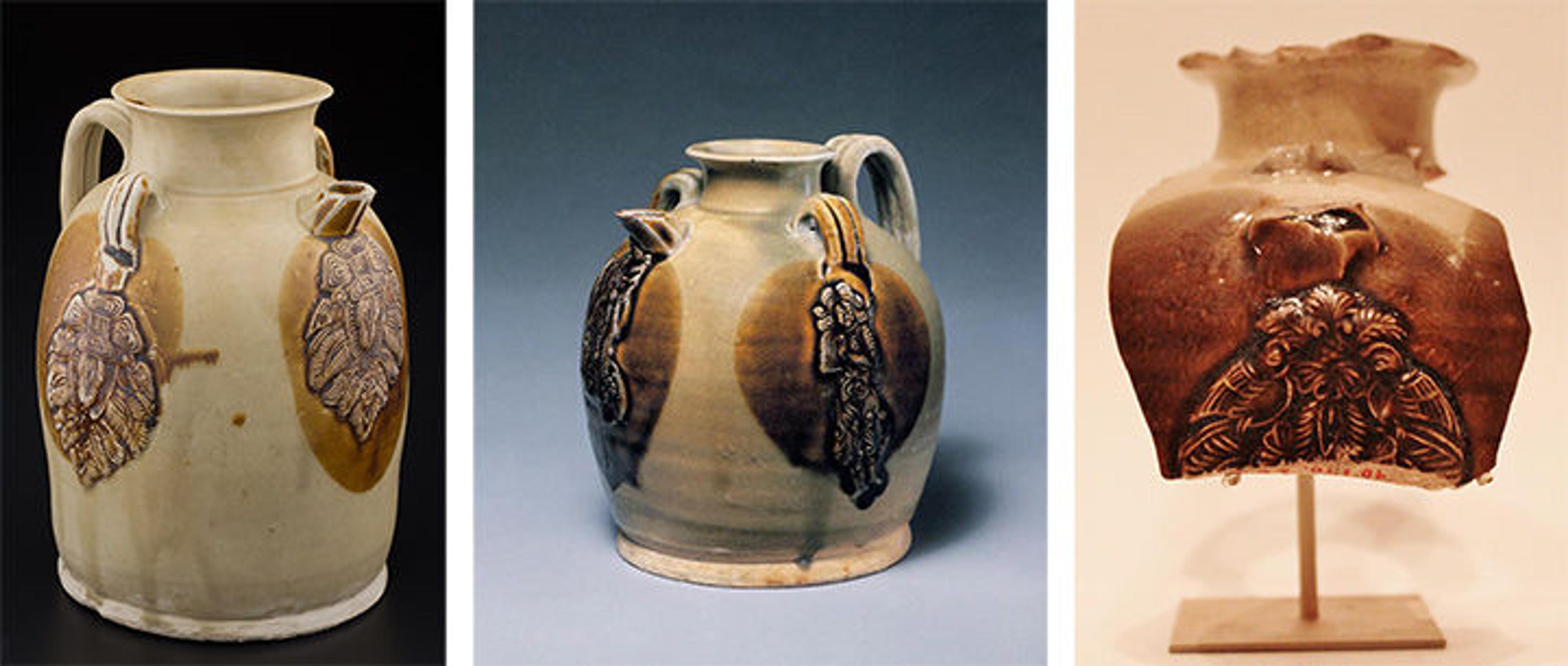

Left: Ewer with date palm and bird decoration, ca. 825–50. China, probably Changsha kilns. Glazed stoneware with molded and applied decoration. Asian Civilization Museum, Singapore (2005.1.00056). Center: Ewer with dancing figure, ca. 9th century. China. Stoneware with white slip, pigment, and applied decoration under straw glaze (Changsha ware). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (1986.113). Right: Fragment of an imported Chinese ewer, 9th century. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Stoneware; molded and glazed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (40.170.455a,b)

Other Changsha wares, such as these two examples from China (above left and center), have applied ornament. The applied decorations form a medallion composed of a cluster of leaves, date palms, or figures, possibly reflecting western-Asian taste. A small Changsha ewer fragment of this type was excavated at Nishapur (above right) and can be seen in the Islamic galleries (gallery 453). Both types of Changsha ware have also been found in Siraf, Samarra, and many sites in southwest Asia.

Chinese, Ding or Xing, Porcelain

Two newly catalogued fragments excavated at Nishapur and datable to the ninth century belong to either Chinese Ding or Xing porcelain ware (Ding and Xing porcelain wares look the same, but their composition is different; the exact type can only identified by scientific analysis) (below left and center).

Left: Newly catalogued Chinese shard, Ding or Xing ware, 9th century. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund. Center: Newly catalogued Chinese shard, Ding or Xing ware, 9th century. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund. Right: Bowl, 9th century. Iraq, probably Basra. Earthenware; painted in blue on opaque white glaze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1963 (63.159.4)

The progressive refinement of porcelain in China was a gradual development from the sixth and seventh centuries to its apogee in the 10th century. A highly valued commodity, porcelain was celebrated in the Islamic lands for its brilliance, smoothness, whiteness, and translucent qualities. A large quantity of imperial-quality Chinese ceramic ware, including porcelain, was given by the Governor of Khurasan to the Abbasid Caliph, Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809), illustrating its importance as a diplomatic gift. Iraqi potters lacked the compositional and technical abilities to create wares of such quality, but they invented an opaque white glaze that masked the yellow body of the clay they used, perhaps in an effort to construct the same level of whiteness (see, for example, the bowl emulating Chinese stoneware, above right). Ding and/or Xing white-porcelain wares are found in other archeological sites in Iran and Iraq, as well as at Nishapur.

Qingbai Ware

Left: Fragment of a [Qingbai] bowl, 9th–10th century. China, excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1940 (40.170.456d). Right: Newly catalogued fragment of a Qingbai ware, A.D. 825–50. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Earthenware; applied relief medallion under three-color glaze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund

Qingbai ware from the Jingdezhen kilns was another highly prized type of porcelain, of which two sherds were excavated at Nishapur (above). This ware has a clear light-blue glaze that was meant to imitate jade. Many pieces of this type reached as far as Fustat in Egypt. These two Qingbai sherds from Nishapur have incised patterns of flowers and leaves.

"Green-Splash" Ware

At the various sites connected to the Gulf trade where Chinese wares have been excavated, original Chinese stoneware known as "green-splash" ware has been found alongside imitations.

Left: Four-lobed bowl with dragon medallion, ca. 825–50. China, probably Henan Province, Gongxian kilns. Stoneware with pale copper-green glaze over white slip. Asian Civilization Museum, Singapore (2005.1.00396). Right: Fragment of an imported "green-splash" bowl, late 7th–first half of 8th century. China; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. Earthenware; applied relief medallion under three-color glaze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (38.40.274)

Original green-splash ware has also been found on the Belitung Shipwreck; an example is a four-lobed bowl with dragon medallion at the Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore (above left). A fragment of a green-splash-ware bowl with a molded dragon medallion from Nishapur (above right) exemplifies the import of rare luxury goods from the Gongxian kilns in the Henan province. Very few examples of this type have surfaced in Chinese contexts, let alone in Islamic lands.

The volume of imported Chinese ware and its impact on pottery production in the Nishapur region in the ninth and 10th centuries bears witness to the high demand for foreign-made and exotic vessels. Even though there are but few traces of Chinese wares in Nishapur, the range in their quality exemplifies the importance of these wares as a commodity of trade for various economic strata of society. As more and more objects are found, either through excavations or shipwrecks, they generate a new understanding regarding the movement of objects and cultural exchange across the wide geographic boundary between east and west Asia, raising the issue of "medieval globalism." The five newly catalogued fragments at The Met add to this discussion.

Note

[1] These are not the only Chinese wares from Nishapur; Charles K. Wilkinson's 1974 book, Nishapur: Pottery of the Early Islamic Period, lists about a dozen other pieces of Chinese ware that were excavated at the site.