Attributed to Sita Ram (active 1814–23). View of a Mosque and Gateway at Motijhil, ca. 1814–23. India, Bengal. Opaque watercolor on paper, 13 x 19 1/4 in. (33 x 48.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2002 (2002.461)

This article, the third in a series of three written by guest author William Dalrymple, explores The Met's collection of Company School paintings, which will be featured in the exhibition Company School Painting in India (ca. 1770–1850), on view at The Met Fifth Avenue from April 10 through October 8, 2017.

«As late as the end of the 18th century, only a handful of Europeans had ever seen the legendary metropolis Shahjahanabad—or, as it was known by its Hindu inhabitants, Delhi—which, within living memory, had been the most spectacularly beautiful city on earth. William Hodges (British, 1744–1797), who had toured India at the close of the 18th century with the intention of making a series of aquatints illustrating the glories of the Taj Mahal and the other great Mughal monuments, thought it "a matter of surprise that a country so closely allied to us should be so little known."[1] But as historian John Keay memorably pointed out, Hodges's revelations made little impression on the socialites of Calcutta: "the price of indigo, Miss Wrangham's engagement, and the shocking case of William Hunter and the three mutilated maidens were more to their taste."[2]»

Certainly, after a century of decline and anarchy, Delhi was not what it once was. It lay half-ruined and sparsely populated, ruled by a blind emperor from a crumbling palace. When Agent to the Governor General William Fraser (1784–1835) finally arrived, "six months and a day after leaving Calcutta," he was astounded by what he saw: the groaning ruins of dynasty after dynasty lay scattered for 30 miles across the plain. Magnificent buildings—tombs, towers, mosques, and palaces—were collapsing, untended, on every side, fueling the young man's desire to recover their history:

The immense extent of ruins which appear all around offer a melancholy picture of the former opulence and population of the city. Archways, porticoes and gateways are all reduced to heaps of desolation. . . . I wish to ascertain historically the account of every remarkable place or monument of antiquity, or building erected in commemoration of singular acts of whatever nature. The traditional accounts I receive from natives are generally absurd or contradictory. I must first know how they obtained credence, and then search for the origins of the story.[3]

A few years later, in 1815, William was joined by another of his brothers, the artist James Baillie Fraser (1783–1856). James found to his surprise that since arriving in Delhi, William had gone native with a vengeance and become himself something of an Anglo-Mughal. He had pruned his moustache in the Delhi manner and fathered "as many children as the King of Persia" from his harem of Indian wives.[4] He loved to discuss ancient Sanskrit texts and composed Persian couplets as a form of relaxation.

Delhi soon worked its spell on James too. James was already producing sketches he planned to work up and publish, a project that would come to fruition in two successful series of aquatints—one on Calcutta and another of the Himalayas. What he saw in Delhi may have inspired him to dream of producing a third volume, this time of views of the old Mughal capital. Certainly his letters home echoed his brother's awe of the crumbling monuments that littered the Delhi plains: "I have been of late literally stunned by views of mosques and tombs and ruins, wrecks of Delhi's former greatness," he wrote to his father. "All the country is covered with tombs of all descriptions, some of great beauty . . . Years would be required to survey all that is worthy of attention. In comparison all our Gothic castles and Roman fortifications sink into nothing. . . ."[5]

Ruins at Old Delhi, 1850s. Albumen silver print, image 6 1/8 x 8 3/4 in. (15.4 x 22.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 (2005.100.948.1 [30])

James had been in Calcutta and had come across the custom, initiated by Sir Elijah and Lady Impey and well established by 1815, of commissioning Indian artists to paint detailed records for their European patrons. During his stay in Delhi, James commissioned a number of artists to paint Delhi figures and monuments, probably as aide-memoirs for his projected aquatint series. The figure paintings have survived and now form what is generally recognized as the most remarkable series of Company School pictures in existence. On display in Company School Painting in India is an image derived from one of those Fraser pictures: Eight Men in Indian and Burmese Costume, painted by the circle of the talented Delhi artist Ghulam 'Ali Khan.

Circle of Ghulam 'Ali Khan. Eight Men in Indian and Burmese Costume, 19th century. India, Delhi. Delhi ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 10 x 15 1/2 in. (25.4 x 39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Julius Hoffman, 1909 (09.227.1)

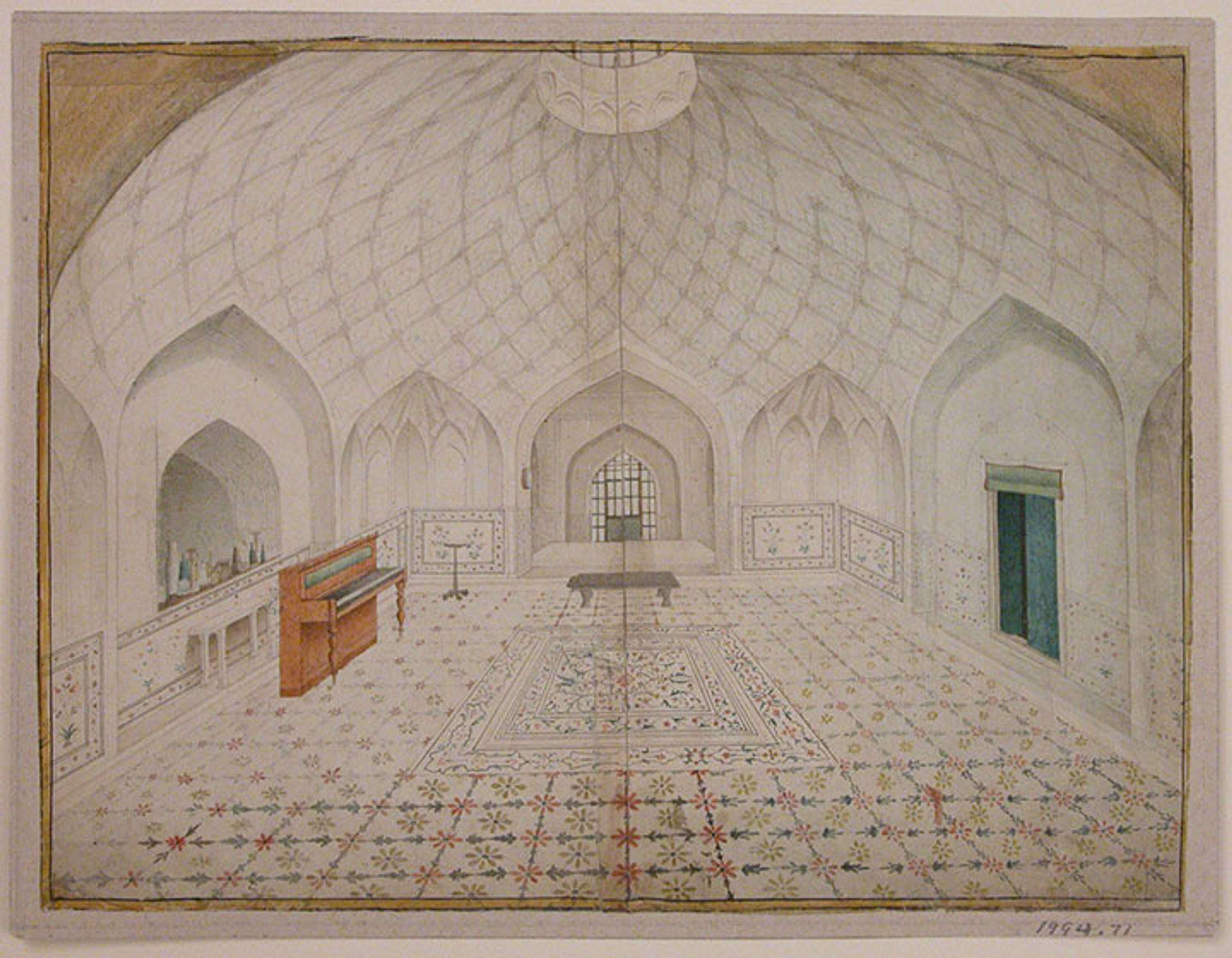

The architectural studies commissioned by the Frasers from Ghulam 'Ali Khan have sadly been lost, but we can get a very good idea of what they might have looked like from surviving architectural paintings produced in Delhi and Lucknow at this period. The finest of the architectural Company pictures, including the paintings of the interior of the hammam (bathhouse) at the Red Fort, Delhi and the painting of the Bara Imambara complex at Lucknow, India, both on display in gallery 464, have the same hypnotic perfection as the Impey natural history paintings (for which, see the first blog post in this series, "The Birth of Company School Painting in Calcutta, India").

Interior of the Hammam at the Red Fort, Delhi, Furnished According to English Taste, ca. 1830–40. India, Delhi. Opaque watercolor on paper, 9 1/8 x 12 1/8 in. (23.2 x 30.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art, 1994 (1994.71)

Artists trained in the Mughal tradition were applying their skills to a very different European art form, that of the objective architectural elevation. The result miraculously combines many of the best qualities of both traditions: the almost fanatical Mughal attention to fine detail is fused with a scientific European rationalism to produce an architectural painting that both observes and feels the qualities of a building.

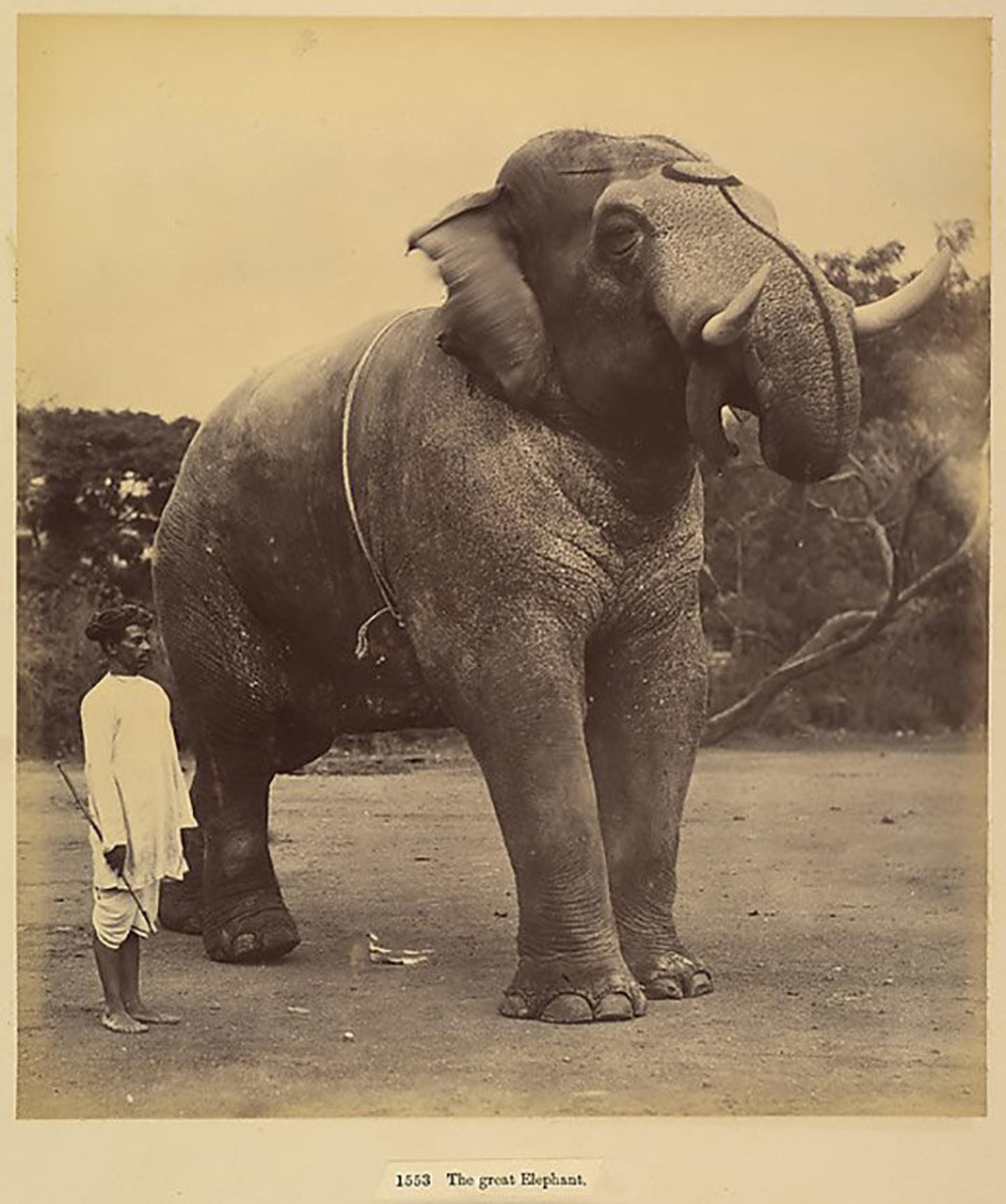

This late Mughal renaissance was destroyed forever in the bloodletting of the Great Uprising of 1857—the largest anti-colonial revolt against any European empire in the world in the entire course of the 19th century. Its bloody and violent suppression by the East India Company was a pivotal moment in the history of British imperialism in India. It marked the end of both the British East India Company and the Mughal dynasty, the two principal forces that had shaped Indian history over the previous 300 years, and replaced both with undisguised imperial rule by the British government. But miniature painting outlived for a while the destruction of the Mughal court, to die a slow and lingering death at the hands not of sepoys or vengeful grenadiers but of photographers, as the new medium slowly replaced the old. Photography was introduced to the subcontinent in the early 1840s, and by 1870 had totally altered the way the court painters went about their work.

Lala Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844–1905). The Great Elephant, 1885–1900. Albumen silver print from glass negative, image: 9 1/2 x 8 3/8 in. (24.1 x 21.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Cynthia Hazen Polsky, 2011 (2011.599.1b)

The artist Val Prinsep (1838–1904) arrived in Delhi in 1877 to collect material for a picture the Government of India wished to present to Queen Victoria as the subcontinent's new empress. Soon after his arrival, Prinsep received a visit from the artists of Delhi, who he discovered now worked entirely "from photographs, and never by any chance from nature." The same marvelous attention to detail is still on show—"their manual dexterity is most surprising"—as is the old fondness for bright, even lurid colors. But this was a last stand. By end of the century many had given up and either become photographers themselves, or else retreated into producing crude reproductions of earlier Mughal work for the tourist trade. Miniature painting as a tradition was now dying, and this was something Prinsep was one of the first to realize. "It is a pity," he wrote, "that such wonderful dexterity should be thrown away." These masterpieces of Company School painting show quite how much was lost.

Footnotes

[1] William Hodges, Travels in India during the years 1780, 1781, and 1783 (London, 1793).

[2] John Keay, India Discovered: The achievement of the British Raj (Leicester: Windward, 1981), 22.

[3] William Fraser to his father, March 20, 1806. From the Fraser papers, vol. 29. Private collection.

[4] Victor Jacquemont, Letters From India, 1829–1832, trans. Catherine Phillips. 2 vols.(London: Macmillan, 1936).

[5] James Baillie Fraser to his father, October 3, 1815. From the Fraser papers, B3. Private collection.

Related Links

Company School Painting in India (ca. 1770–1850), on view at The Met Fifth Avenue from April 10 through October 8, 2017.

View other blog articles related to this exhibition on the Department of Islamic Art's blog, RumiNations.