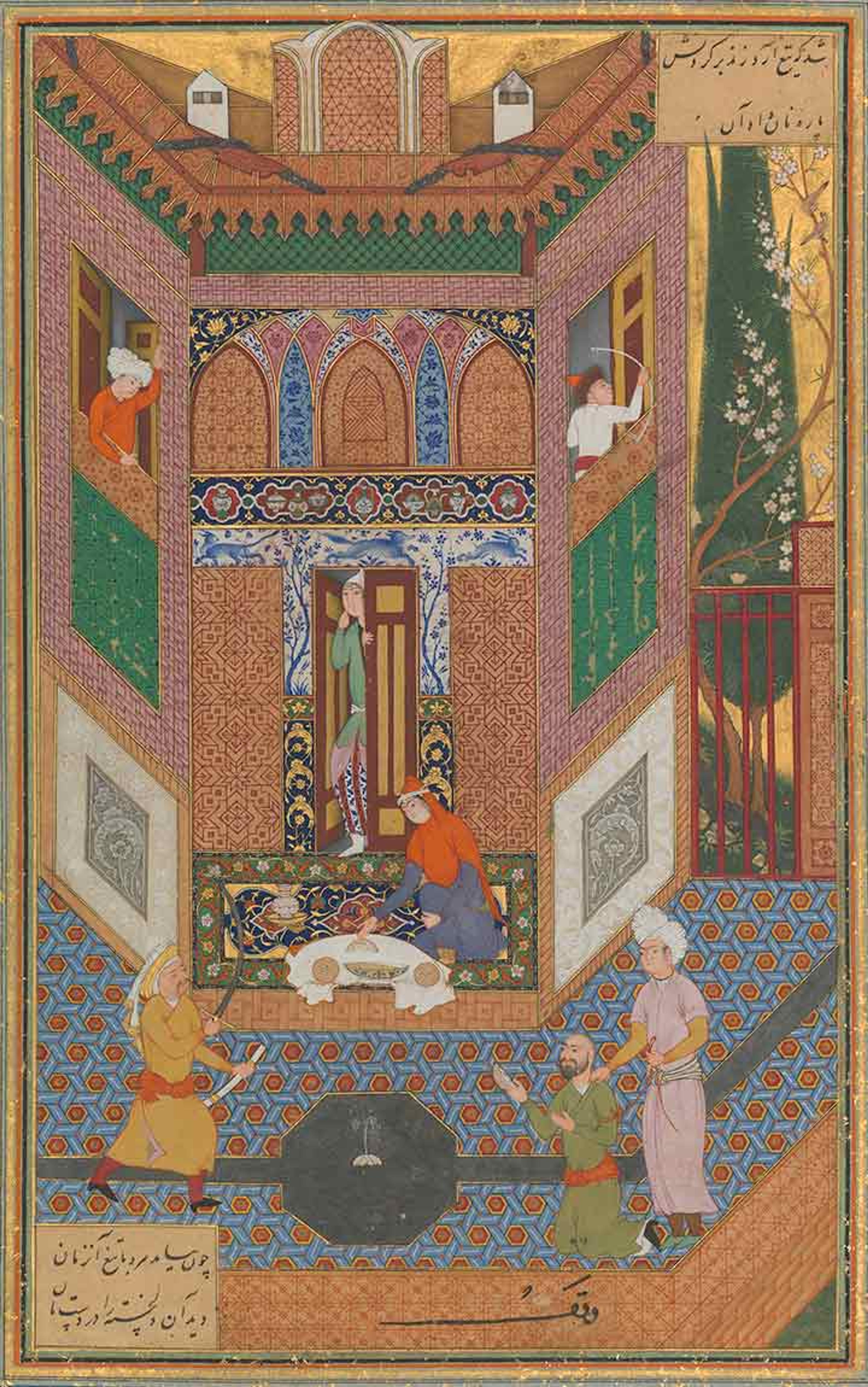

"A Ruffian Spares the Life of a Poor Man," ca. 1600. Folio 4v from an illustrated manuscript of Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds; or The Conference of the Birds), by Farid al-Din 'Attar (ca. 1142–1220). Iran, Isfahan. Ink, opaque watercolor, silver, and gold on paper; painting: 7 3/4 x 4 1/2 in. (19.7 x 11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1963 (63.210.4)

«The Conference of the Birds, Farid al-Din 'Attar's (ca. 1142–1220) medieval classic, is one of the most adored masterpieces of Islamic literature. Arguably the finest illustrated copy of this Sufi tale, a manuscript with eight paintings from the Timurid court of Sultan Husain Baiqara (r. 1470–1506) and the Persian court of Shah 'Abbas I (r. 1587–1629), is in The Met collection. This manuscript was originally copied by the great 15th-century Persian calligrapher Sultan 'Ali of Mashhad. Later, in the 17th century, a painting was added to illustrate the first anecdote in the book, "A Ruffian Spares the Life of a Poor Man." This illustration does more than offer a literal representation of the story; it contains a number of allusions (Persian: ishārā) that reveal the story's hidden meanings and enrich its theme of pleading for God's mercy.»

The Story

The story of the ruffian appears in the prologue to The Conference of the Birds. The prologue is constructed around a famous utterance of the prophet Muhammad in which God declares, "My Mercy precedes my Wrath" (Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 97, Hadith 178). In this prologue the author, Attar, describes how he visited the court of God. Realizing that only one in 100,000 is chosen for sanctification, he begs God to "Bestow on me good fortune, since I come in poverty." Quite abruptly, this prayer is followed by the brief story of the ruffian, in which a bandit drags home a wretch in order to rob him and eventually take his life:

A bandit dragged a wretch home to his lair

And tied him up, and meant to kill him there;

He drew his knife to sever the man's head

Just as his wife gave him a bit of bread.

He was about to kill the wretch, then saw the bit

Of bread, and asked how he had come by it:

'Who handed you that scrap of bread I see?'

The wretch replied: 'Your wife gave it to me.'

And hearing him the bandit said: 'Then I

Can't be the lawful means by which you die,

Since, when a man breaks bread with us, to draw

A knife against him is to break our law;

A man who shares our bread's our friend—how can

I even think of killing such a man?'

Farīd al-Dīn 'Attar, The Conference of the Birds, trans. Dick Davis and Afkham Darbandi (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1984)

Following the brief tale, the poet makes an impassioned appeal to God's mercy with words that suggest the story's underlying significance: "My King, You saw the wretch I was; I vow the sins You saw are gone; look at me now—I sinned from ignorance and carelessness; forgive my sins and pity my distress."

In Sufi allegorical tales such as this that feature multiple characters, more than one person can represent the qualities of God or various aspects of the soul. In the story of the ruffian, both the bandit and his wife are regarded by traditional interpreters as being two distinct attributes of God. The ruffian is God's Justice (Al-'Adl), and his wife is God's compassion in its active form (Al-Rahim). The wretch himself is none other than the repenting soul who has been dragged, utterly destitute and desperate, into the court of the Just.

The Illustration

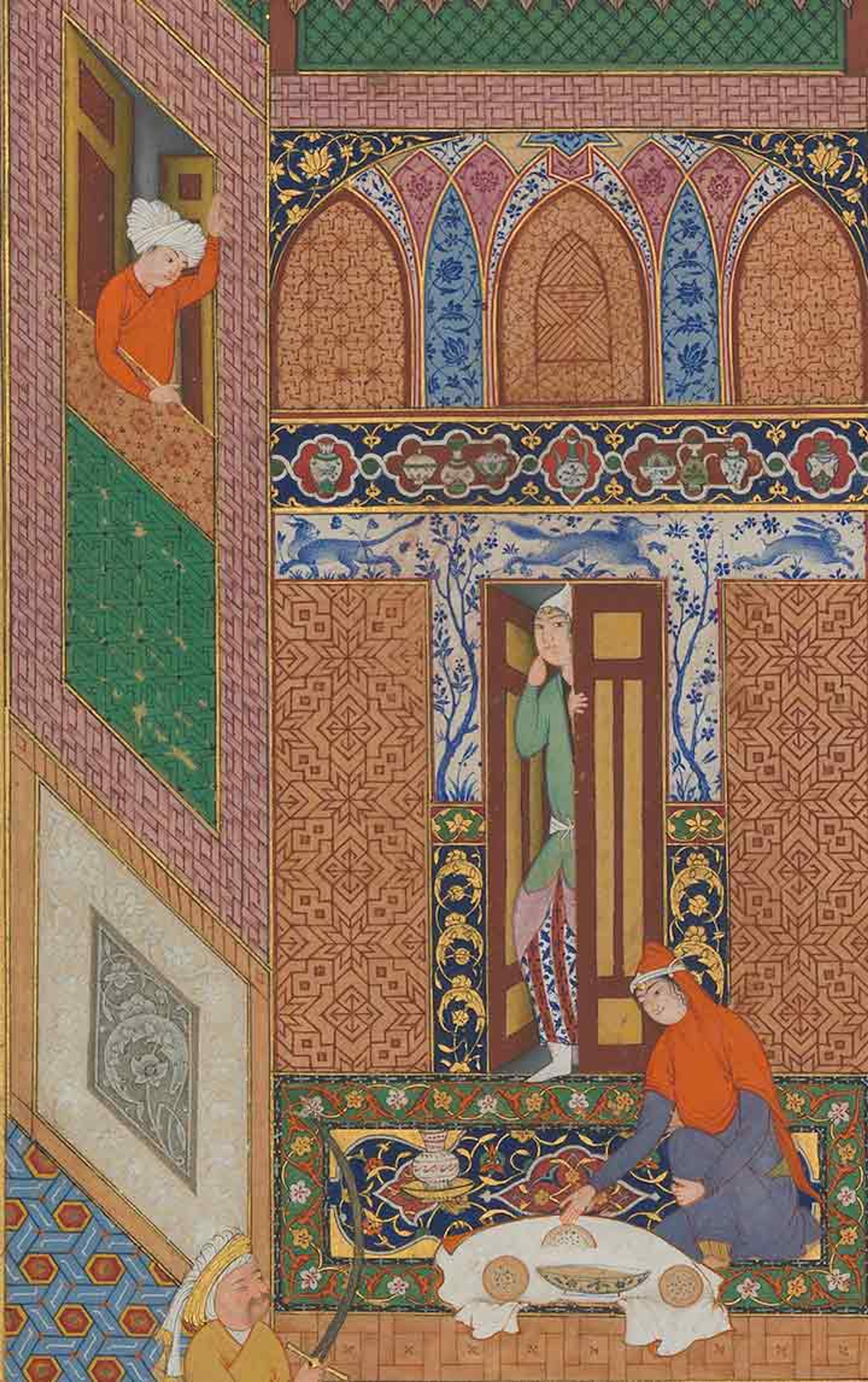

The main scene takes place in the richly tiled courtyard of the ruffian's two-story house. In keeping with 16th- and 17th-century Persian architectural conventions, the house is depicted with an elaborately decorated geometric facade.

In the porch to the main entranceway, the bandit's wife lays a loaf of freshly made bread on a serving cloth. A woman, presumably the wife's servant, peeps out from the main doorway, making a conventional gesture of surprise, with her index finger to her mouth.

Framing the doorway is a fresco depicting a fox hunting rabbits in the woods. The fresco relieves the rigid geometry of the facade, bringing light and air into the overall symmetry of the composition.

Above, on the left-hand balcony, a figure peers down at the central scene. Like the servant girl, he inhabits a liminal space connecting the interior of the house with the outdoors. The two voyeuristic figures function as intermediaries between the viewer and the viewed.

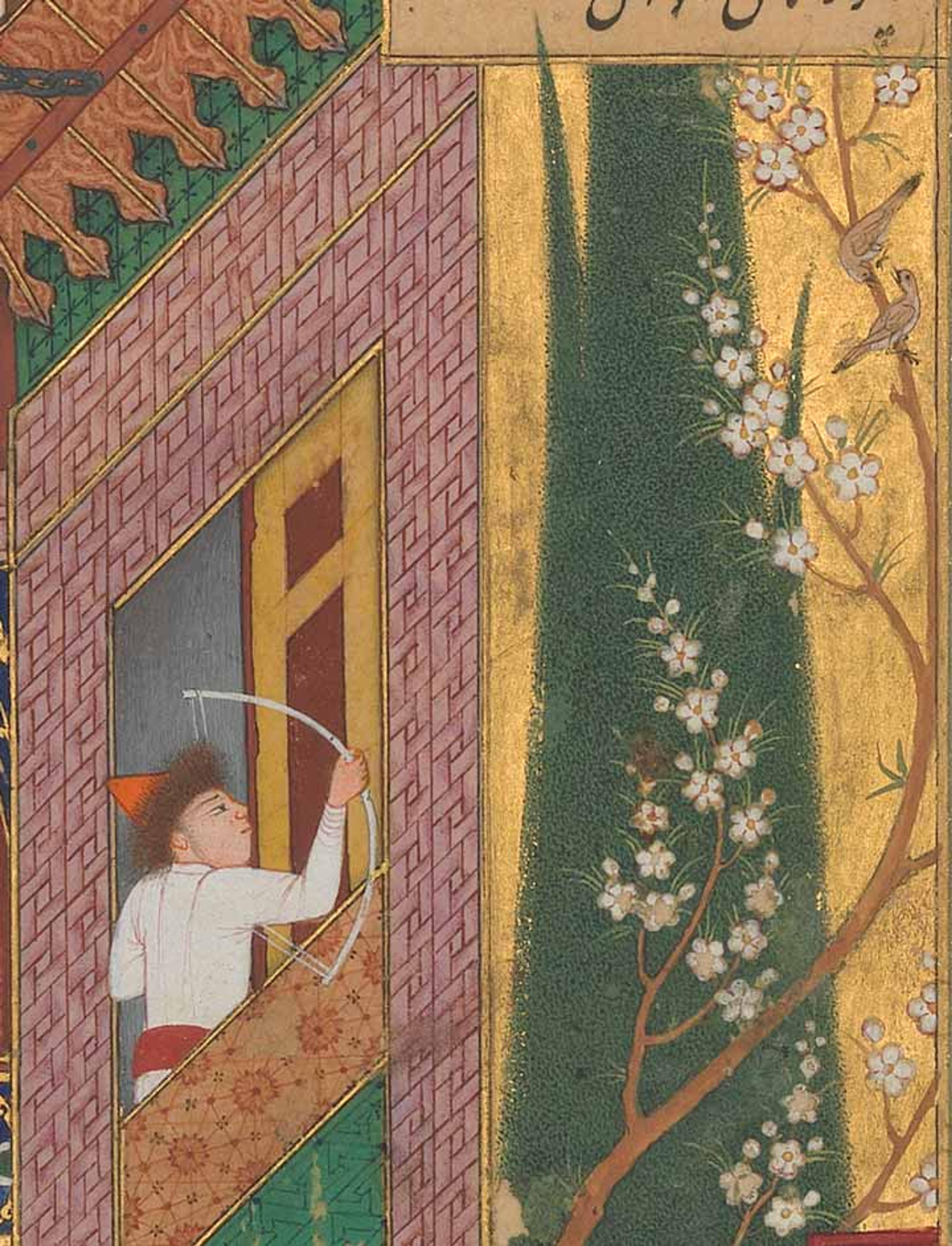

On the other balcony, a third figure looks into the distance, completing the symmetry of the triadic composition. Clad in white, he has just notched an arrow and is about to shoot one of two birds perched atop the branch of a winding tree that snakes across a cypress. Beyond the garden, the sky is a resplendent wash of shell gold. Further up, the artist uses the conventional device of multiple perspectives to present a view of the roof, where smoke wafts from a chimney almost directly above the kneeling wretch. The two trees in the garden are the only elements that break out of the frame, at upper right.

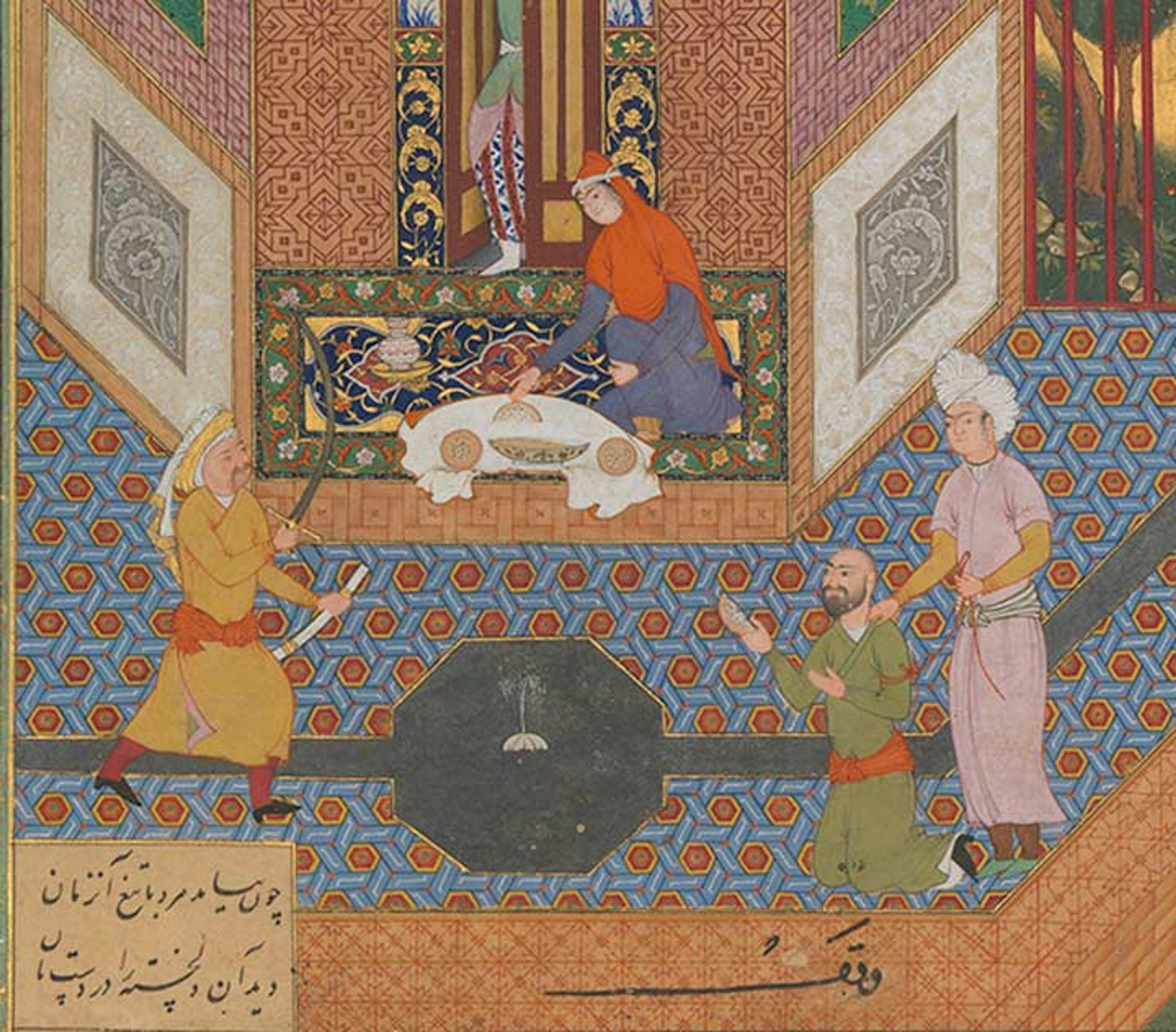

The main action unfolds around a central fountain. The two protagonists are carefully positioned on either side. The kneeling wretch is daintily tied with a thin red rope grasped by a male servant. The image focuses on the moment of greatest anticipation and suspense. The ruffian has just drawn his sword and is shown lunging towards his victim. The wretch pleads with him desperately, while clutching half of the loaf baked by the ruffian's wife. The ruffian has just noticed the bread. The wretch has just begun to give his answer. His fate hangs by a thread.

The Allegory

Attar's story has three main characters. The illustration echoes this by presenting various intriguing groups of three. The protagonists form a triangle with the fountain at the center. This human composition is mirrored by the three loaves of bread placed on the white serving cloth with the tray at the center. The wife, who represents God's compassion, touches half of the loaf; the wretch grasps the other half, thereby linking God's mercy with the supplicant. The three animals in the fresco above the door form another triangular composition, as do the three figures inside the building, who rest in the liminal space between interior and exterior. The archer imitates the fox in the fresco in that, like the fox, he has two objects of prey in sight.

A second visual convention, the motif of the hunt, is ingeniously employed to heighten the sense of drama. In the story, the killing of the wretch has an air of inevitability, almost as if it were unfolding by the laws of nature. This inevitability is expressed in several ways in the painting. In Muslim belief, it is regarded as natural law for us to be judged at the moment of our death by the sword of God's purification, just as it is the nature of the fox to hunt prey and the archer to hunt birds. However, all of this is superseded by God's mercy. In the image, the wretch has not yet been pardoned; his fate hangs in the balance. The fox is also about to pounce on its prey. Similarly, the archer has notched and drawn his arrow, but has yet to release it; the tension is palpable in the curved bow and the taut bowstring. In all three instances, the prey has not been struck: "My mercy precedes My wrath" (Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 97, Hadith 178).

In 'Attar's prologue, God's mercy can only be accessed when the supplicant comes to His threshold, completely poverty stricken and desperate, and makes a heartfelt prayer. The plea of the wretch, like the poet's ardent prayer, is expressed by the smoke from the chimney. Rising to the heavens, the smoke seems to imitate the trees in their progression out of the picture frame and into the gold-sprinkled sea of blue. The smoke itself has been created by baking the bread that acts as the agent of compassion. Thus, God's compassion is already inherent in the supplicant's plea; and, like the bread, His mercy has preceded the wrath of the ruffian's sword.

This single image, like other images in Persian Safavid painting, thus presents a striking visual narrative that not only supports the text it accompanies, but also stands independently, offering a complete depiction and an interpretive perspective on a traditional tale.

Related Link

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "The Mantiq al-Tayr of 1487"