Fig. 1. Petticoat panel, third quarter 18th century. Indian, Coromandel Coast, for the Dutch market. Cotton, painted resist and mordant, dyed; 33 5/8 x 67 1/2 in. (85.4 x 171.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Gifts, 1992 (1992.82)

«The Met's Department of Islamic Art holds a rich collection of painted cotton textiles from 17th- and 18th-century India. These cloths—known in Britain as chintz, in India as chīnt, and in Iran as čīt,—are cotton cloths painted with dyes. The origin of the term chintz points to this duality of the medium, with some historians saying the word chīnt comes from the elevated vichitra, the Sanskrit for something painted with a picture; in this formulation a chīnt or chintz is a painting. Others say it comes from chītna, a verb meaning to spot or sprinkle, a term that would permit more appreciation for the dyeing of the cloth and the saturation of its colors.»

Of course the contemporary associations with the word chintz, or chintzy, refer to something tacky or outdated, a meaning that arose in 19th-century Britain and was first documented in the letters of the writer George Eliot. Over time, chintz began to refer to a type of pattern, which drew attention away from the historical significance of the dyer and the 17th-century value of the cotton cloth's saturated color. The exhibition The Secret Life of Textiles: Plant Fibers—organized by the Department of Textile Conservation and on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in the Antonio Ratti Textile Center through July 31—provides a deep examination of plant fibers and explores the challenges of dyeing cloths made from cotton.

As a postdoctoral fellow this year, I have had the opportunity to study the department's collection of painted cotton cloths in the Ratti Center. Aided by a microscope, I have been able to see the veiny blue lines that indicate that indigo dye seeped through the wax meant to keep portions of the cloth its original white. Even the opportunity to see the backside of a textile can reveal valuable information about how deeply the dyes have saturated the cotton fibers.

Conversations with curators in the Departments of Islamic Art, Asian Art, European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, and the American Wing, and with members of the Departments of Scientific Research and Textile Conservation, have led me to realize the importance of the dyer to the production of these painted cotton cloths. I have come to see chintz as a special medium in which the surface decoration merges completely with the support, as the colors used to paint designs fully saturate the cotton fibers.

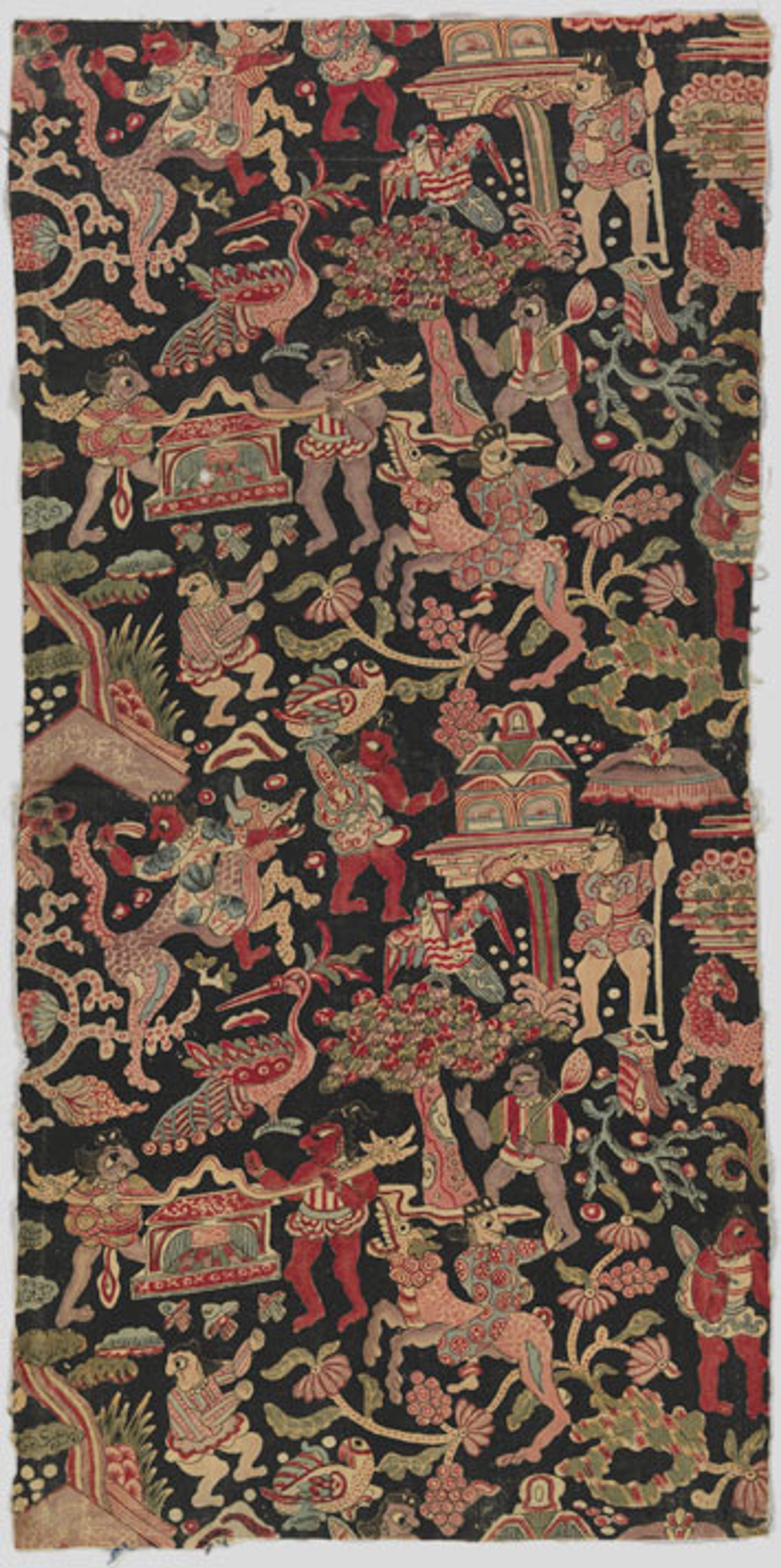

Fig. 2. Sarasa with figures, birds, and fantastic animals, late 17th–early 18th century. India (Coromandel Coast), for the Japanese market. Cotton (painted resist and mordant, dyed); Overall: 27 1/2 x 13 3/4 in. (69.9 x 34.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2010 (2010.56)

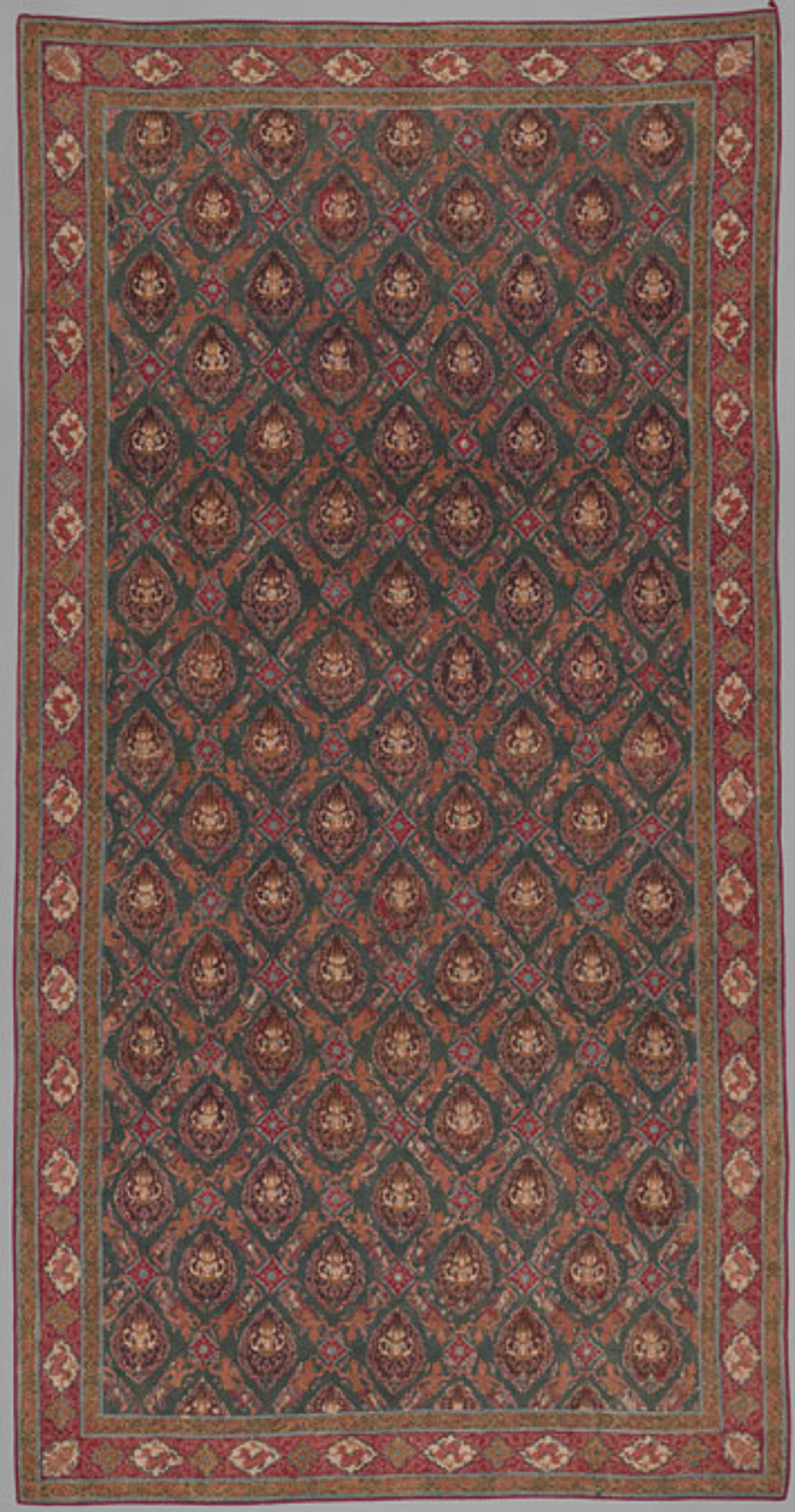

In the 17th century, chintz cloths were produced along what was known as the Coromandel Coast, a region with a history of lively maritime trade with ports throughout the Indian Ocean. Painted cotton textiles were wildly popular with consumers throughout Europe (fig. 1), East Asia (fig. 2), and Southeast Asia (fig. 3), as well as North Africa, Turkey, and Iran. Chintz cloth even traveled on Spanish galleon ships to the Americas, where the textiles were known as indianillas. Yet on the local level, chintz grew out of a highly developed economy of exchange and a sophisticated division of labor.

Right: Fig. 3. Floor covering or hanging (Pha Kiao), 18th century. India (Coromandel Coast), for the Thai market. Cotton (painted resist and mordant, dyed); Overall: 83 x 43 1/8 in. (210.8 x 109.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Huntington Norton, 1944 (44.71.2)

After bleaching in lemon or lime and sheep's dung, cotton cloth was distributed to textile painters and dyers, who often relied upon resources in the surrounding environment rather than commercially sold pigments. Dyestuffs ranged from the indigo, which was grown and processed commercially, to the famous red dye known as the chay root, which grew in the calcium-rich soil of southeastern India's river deltas. Turmeric could be made into a yellow dye or combined with indigo to produce green. Pomegranate rinds produced a deep mustard-colored dye, but could also yield green in the pista'i, or pistachio color. Henna was a necessary component to produce deep orange dyes. The dyer's task was to collect these dye materials, dry them, pound them into a fine powder, and then to mix them with metallic mordants in a dyebath, the acidity or alkalinity of which the dyer controlled with citrus, lime, and ash.

Chintz raises the question of which artisan receives credit for the cloth—a complication that points to the intricate nature of the medium itself. Chintz is the craft of the painter who traces out, with a steady hand, the lively lines of the pattern, but it is also a dyer's art, for it is the dyer who makes the adjustments needed to achieve the precise colors and ensures their lasting brightness. The challenges faced by the cloth painter were distinct from those of the oil or fresco painter; in reality they were the challenges of a dyer.

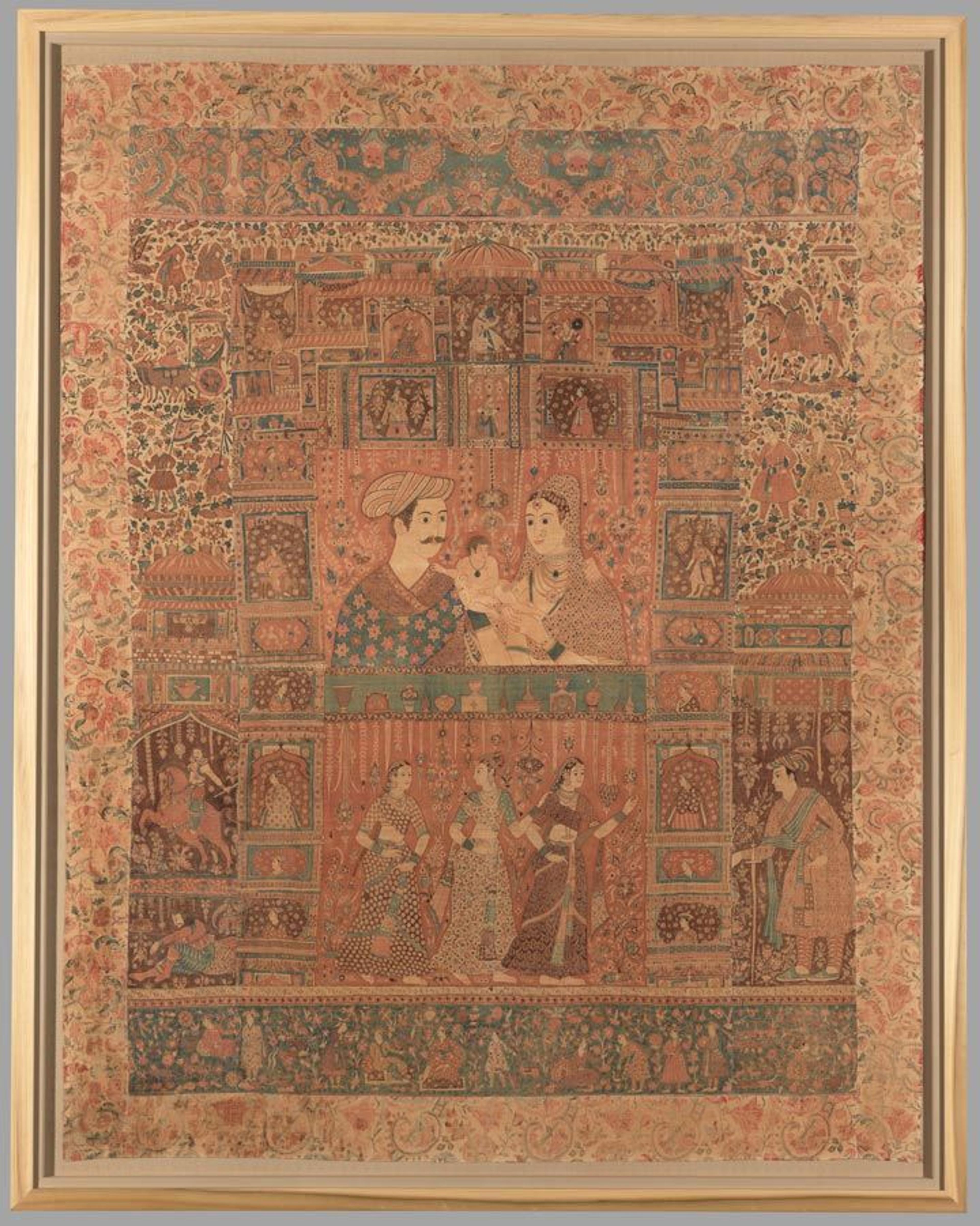

Fig. 4. Kalamkari hanging with figures in an architectural setting, ca. 1640–50. India, Deccan. Islamic. Cotton; plain weave, mordant-painted and dyed, resist-dyed; Textile: L. 100 in. (254 cm), W. 78 in. (198.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Albert Blum, 1920 (20.79)

A painted cotton hanging in The Met collection suggests the relationship between painter and dyer perhaps better than any historical account could. Seen last summer in the exhibition Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy, this virtuosically painted cloth measures nearly eight feet tall and six feet wide. In the delicate rendering of the faces of the central couple and their chubby child, the painter has captured the soft curve of the mother's face and has painted her tapering fingers with calligraphic lines.

These fine lines were drawn in a thin, iron-based black dye that the painter dispensed from a egg-shaped cotton reservoir on his bamboo pen. The difficulty lies in keeping the liquid dye moving along the cloth in an even line without letting it pool. In the eaves above, the painter has depicted lively scenes of a woman holding her bird, a seated man fanning himself, and the proud, mustachioed figure of a portly man. Below, a wild-eyed horse stippled in red dots rears on its hind legs.

However, it was the dyer's work that impressed me when I examined this textile in the Ratti Center. The dyer gave the figures warm flesh and rose-colored lips using subtle applications of pink and brown dye. By creating gradations in the brown color of the man's robe, the dyer allowed the humble cotton fabric to evoke a textured silk velvet. If one looks closely at the choli blouse worn by the central veiled woman, it contains a pattern of small white stars that suggests a finely woven jamdani cotton cloth similar to those discussed in a recent Ruminations post. To create this white pattern against the woman's pale skin, the dyer must have used a wax or mud "resist," which protected the white stars from the colors of the dyebath.

Cloths painted with dyes exist right at the fault line between art history and material culture, requiring us to move between the sticky, unglamorous stuff of dung-based bleaches and fermented indigo, and the aesthetic, disembodied relief of the painter's calligraphic line. Chintz can help us to broaden the definition of art making by asking us to look beyond the surface decoration of flowers and figures to the colors that give them life.

Resources

Crill, Rosemary, ed. The Fabric of India. London: V&A Publishing, 2015.

Gittinger, Mattiebelle. Master Dyers to the World: Technique and Trade in Early Indian Dyed Cotton Textiles. Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum, 1982.

Houghteling, Sylvia. "From Foot-cloth to Petticoat: The British Uses of Indian Chintz ca. 1700." In Setting the Scene: European Painted Cloths 1400–2000, edited by Christina Young and Nicola Costaras, 51–57. London: Archetype Books, 2013.

Peck, Amelia, ed. Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500–1800. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

Sardar, Marika. "A Seventeenth-Century Kalamkari Hanging at The Metropolitan Museum of Art." In Sultans of the South: Arts of India's Deccan Courts, 1323–1687, edited by Navina Najat Haidar and Marika Sardar, 148–61. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

Related Links

The Secret Life of Textiles: Plant Fibers, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 31, 2016

RumiNations: "In Search of Bangladeshi Islamic Art" (November 12, 2015)