Fig. 1. Woven tapestry fragment, mid-8th century. Iran, Iraq, or Egypt. Islamic. Wool; tapestry weave; Textile: L. 12 in. (30.5 cm), W. 18 3/4 in. (47.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1950 (50.83)

«The collection of the Department of Islamic Art at the Met has been a prime research source for study during my time at the Institute of Fine Arts. This fall, I'm delighted to have the opportunity to work in the department as an intern, and to reconsider some of the artwork that I viewed only briefly during previous coursework. Among such objects, an Umayyad wool tapestry fragment particularly made me recollect my thoughts, which then led to a new consideration of the object (fig. 1).»

Exact repetitions of carefully calibrated motifs may be an impression that Islamic art leaves on many people, especially for those who look at ornamental art. While this tradition holds true for many objects—including ceramic wares, tiles, and carpets—it is actually less universal than it appears to be. This tapestry fragment not only offers a great counterexample, but also reveals a glance at the more playful spirit of early Islamic textiles.

Attributed to a Middle Eastern or North African origin, the fragment has been dated to the mid-eighth century, which associates it with the Umayyad Caliphate, the first Islamic dynasty. The elaborate rosettes and floral motifs, although stylized, can be read as bright flower sprays emerging from a grassy background. Despite its fragmentary nature, the tapestry has three ends without traces of a selvedge, or finished edge, which suggests that the fragment may have been a small part of a much larger article, very likely a furnishing fabric. However, the extreme rarity of extant Umayyad textiles has made it almost impossible to reconstruct the furnished Umayyad homes of the seventh or eighth century. Still, wall paintings and mosaics from the Umayyad palaces can provide us some clues of interior decorations.

A fresco at Qusayr 'Amra, for example, shows a ruler leaning on an elevated couch and talking to two attendants (fig. 2). He is attended by a servant while a chronicler is standing in the background and scribbling down the conversation. In contrast to the austere, current state of the interiors of Umayyad palaces, this fresco depicts a heavily draped space where doorways and colonnades are veiled and seatings are covered.

Fig. 2. Umayyad frescoes at Qusayr 'Amra, Jordan. Photograph by Eve Mayberger and published on the Conservation Class of 2016 Blog, Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

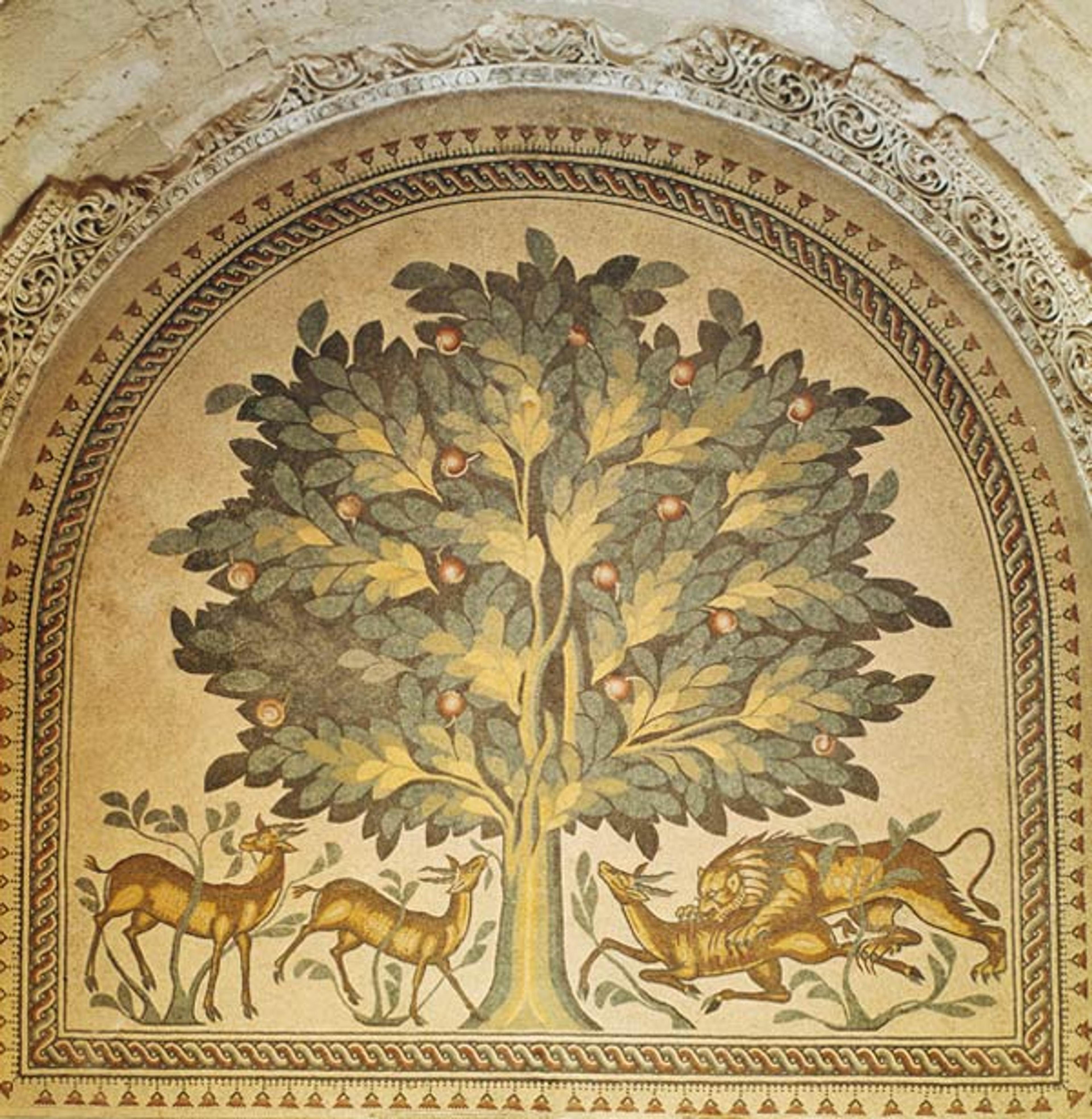

The floor mosaics at the entrance of the Khirbat al-Mafjar, another important Umayyad palace, also hint at the presence of textiles. The mosaic within an arched border is exquisitely edged with tassels, suggesting the possible existence of a carpet of similar size (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Mosaic pavement with a lion and gazelle, 724–43 or 743–46. Reception hall, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Palestinian Territories. Photo courtesy of Scala/Art Resources, NY

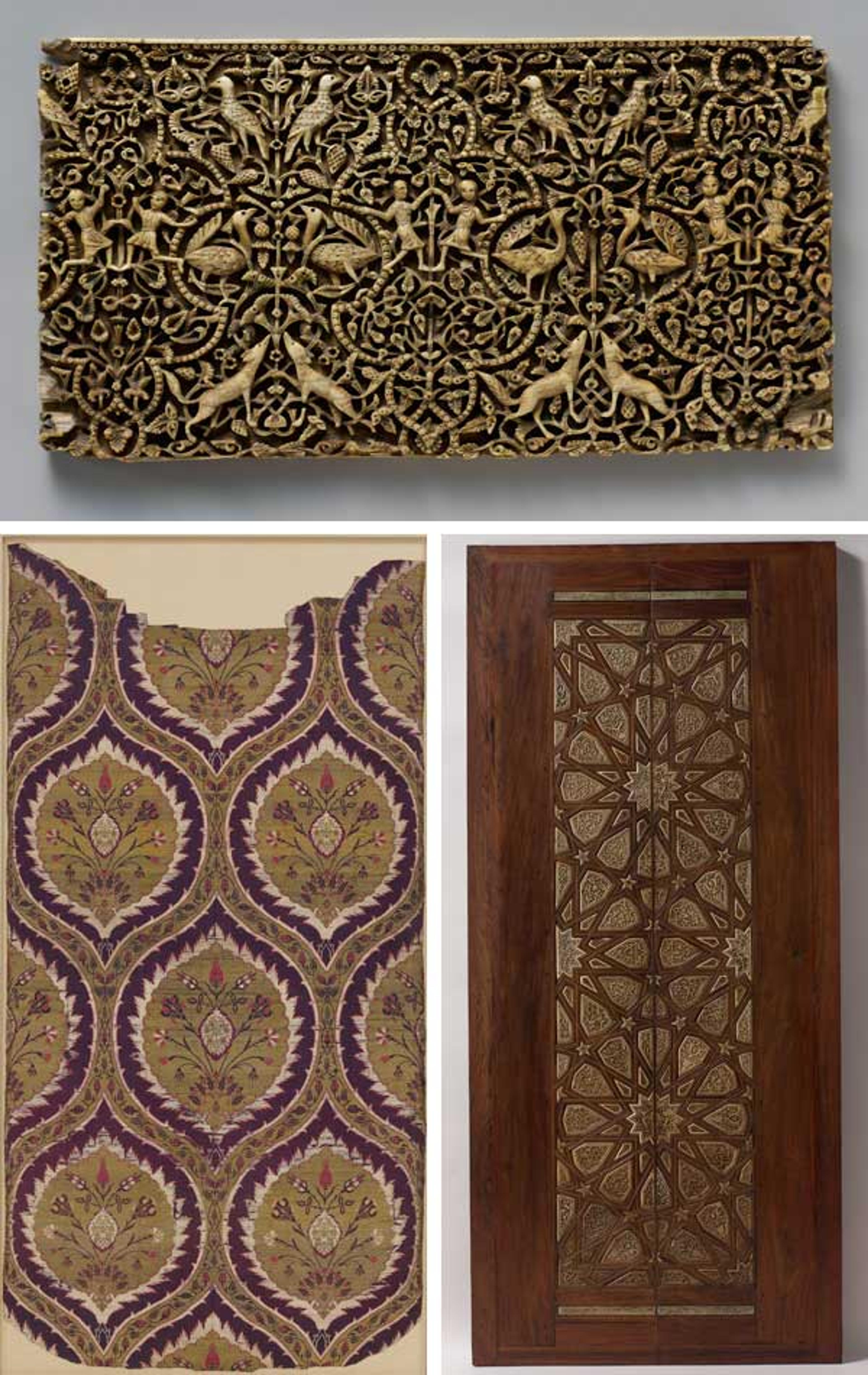

Given such examples, our floral tapestry fragment might originally have been a wool seat or wall furnishing. What particularly interests me about it is the irregular design of the motifs and their varied color applications, as decorative art from later Islamic dynasties generally tends to pursue either strictly repetitive or symmetrical layouts.

Three examples of decorative art from later Islamic dynasties that feature repetitive or symmetrical layouts. Top: Panel from a rectangular box, 10th–early 11th century. Spain, probably Cordoba. Islamic. Ivory; carved, inlaid with stone with traces of pigment; H. 4 1/4 in. (10.8 cm), W. 8 in. (20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1913 (13.141). Bottom left: Fragmentary loom width with ogival pattern, ca. 1580–80. Turkey, probably Istanbul. Islamic. Silk, metal wrapped thread; lampas (kemha); Textile: L. 75 in. (190.5 cm), W. 26 in. (66 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, 1949 (49.32.79a–y). Bottom right: Pair of minbar doors, ca. 1325–30. Cairo, Egypt. Islamic. Wood (rosewood and mulberry); carved, inlaid with carved ivory, ebony, and other woods; H. 77 1/4 in. (196.2 cm), W. 35 in. (88.9 cm), D. 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891 (91.1.2064)

By contrast, this tapestry fragment, although still following a generic pattern, displays a cluster of floral motifs that are each slightly nuanced. The band with a green background, presumably part of the center area of the original textile, shows two rows of medallion-style rosettes. In this case, all the seven rosette motifs are distinctive either in color or in form. Upon closer inspection, the "petals" are also individually rendered for each rosette. The flower bouquets on the red band, the edge, are woven in a similar fashion so that no neighboring motifs are exactly the same. I believe all these varied presentations are intentionally designed.

Such variety in repetition is also visible in the phenomenal facade of Qasr al-Mshatta, which stages a parade of carved rosettes in hexagons and hexafoils (fig. 4). Within the same outlines that keep the general form in order, each rosette bears distinctive content, while a world of lions, griffins and peacocks is presented in the interspace densely covered by grape leaves. It is therefore likely that decoration programs as such were manipulated to present a garden with a variety of flora and fauna, hence imitating the fabled Paradise garden.

Fig. 4. Facade of Qasr al-Mshatta as installed in the Pergammon Museum, Berlin. Photo © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

In this case, the rosette tapestry fragment from the Met's collection, whether used as a hanging or a cover, would have transformed into one segment of a mobile garden that could be easily carried by any individual. When the owner spread the tapestry, a miniature of Paradise would be released and add glamour to the environment as if the person were sitting on a floral lawn or surrounded by fantastic creatures.

Reference

Trilling, James. The Medallion Style: A Study in the Origins of Byzantine Taste. New York: Garland, 1985.

Related Links

RumiNations: "From the Ground Up: Conservation Treatment of an Indian Textile" (August 18, 2015)

Read more about the Curatorial Studies program jointly administered by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Institute of Fine Arts.