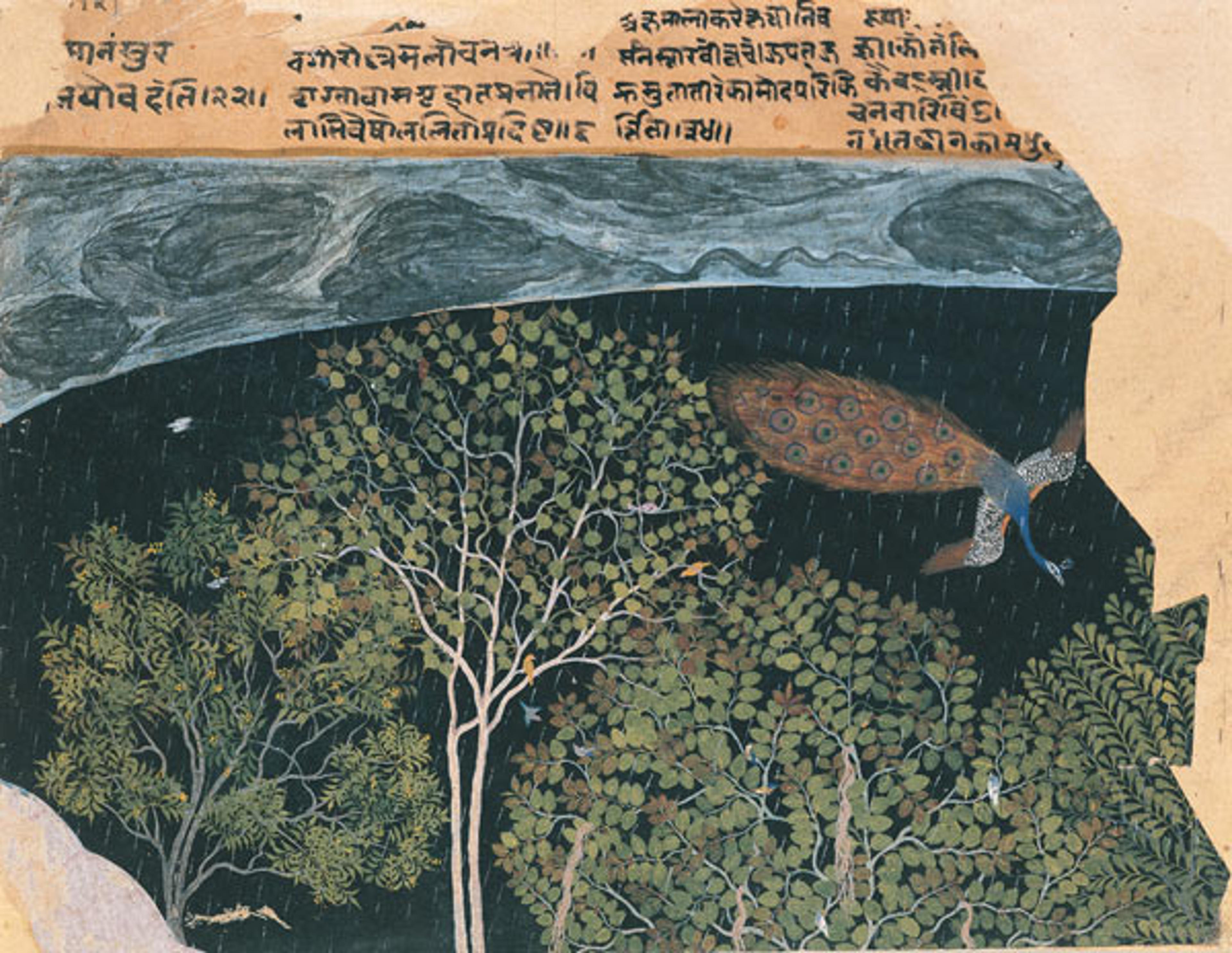

Peacock in a Rainstorm at Night, late 16th century. India, Northern Deccan. Non-Islamic, Hindu. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; 6 1/8 x 7 1/2 in. (15.5 x 19 cm). Private Collection, London

«As Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy came to a close this past weekend, I I took some time to examine a genre of paintings that has particular resonance for me and my work at the Met: ragamala paintings. Translated as "garland of ragas," ragamala paintings represent a fusion of music, poetry, and painting, providing one of the most compelling examples of the interconnectedness of art forms in the Deccan. Particularly at the Met, these works get to the essence of what we hope to do in our public programming: create an experience for visitors that generates connections between the visual, performing, and literary arts.»

In India, it was the centuries-old musical system of ragas that first inspired poets to compose texts involving deities and humans, which helped the listener achieve a deeper sensation of the music. This writing, in turn, inspired painters to produce visual works that further evoked the emotional quality and religious meaning of the music. This style of ragamala paintings ultimately reached its pinnacle in Northern India during the sixteenth century, in the regions of Bijapur and Ahmadnagar.

The Deccan exhibition contained a stunning selection of ragamala paintings, including the mysterious Peacock in a Rainstorm at Night—a painting that immediately stands apart from the three pieces beside it because of an imperfection: the bottom half is torn off, which both makes the piece smaller, and also makes it appear horizontal rather than vertical. Beyond this, it is striking that the picture contains no people. Typically the figures would have occupied a prominent space in the central-bottom section. In this case, however, we are instead left to focus on an expanse of land, sky, and animals in the remaining fragment.

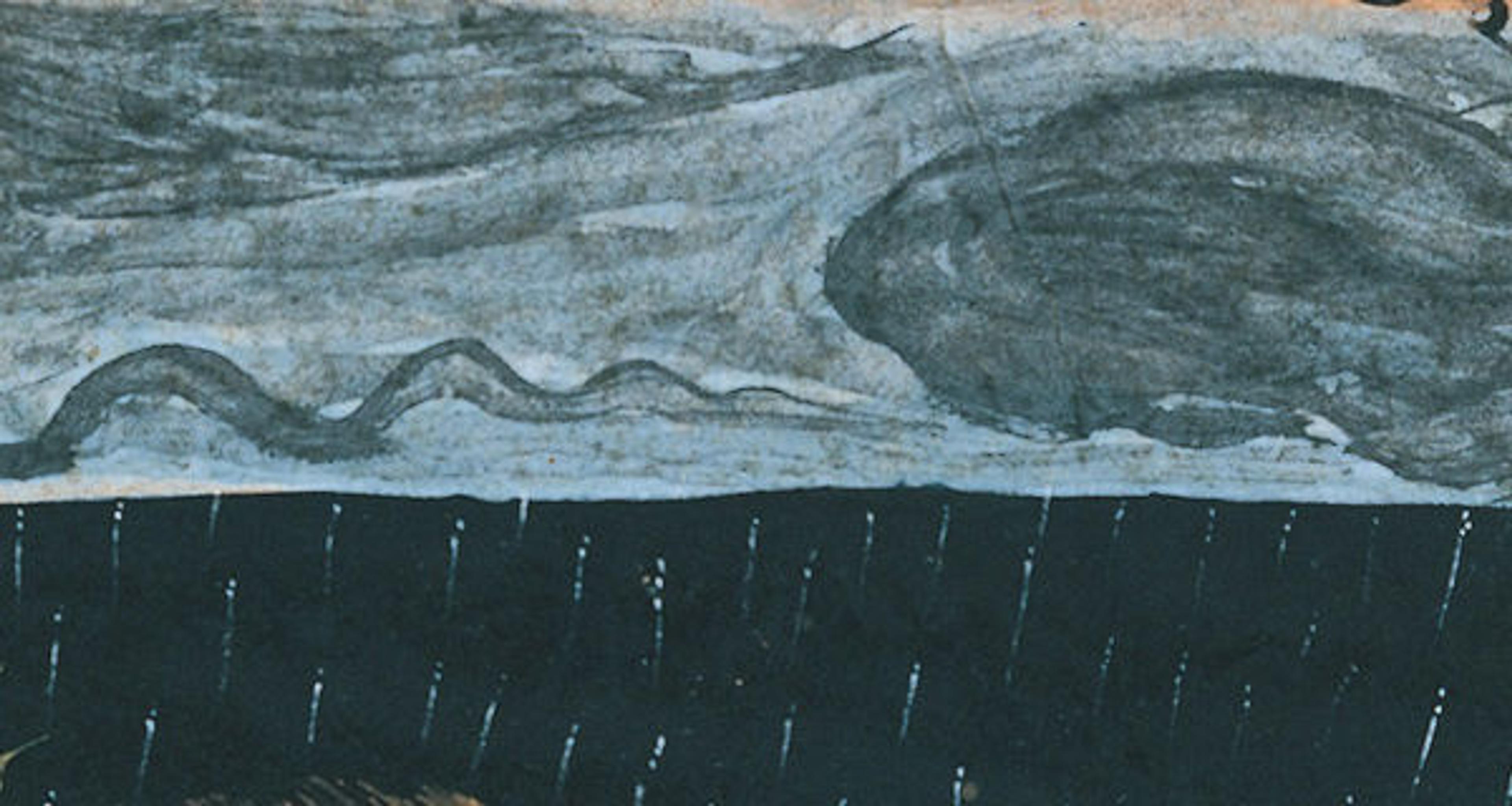

Detail view showing the sky and monsoon rains

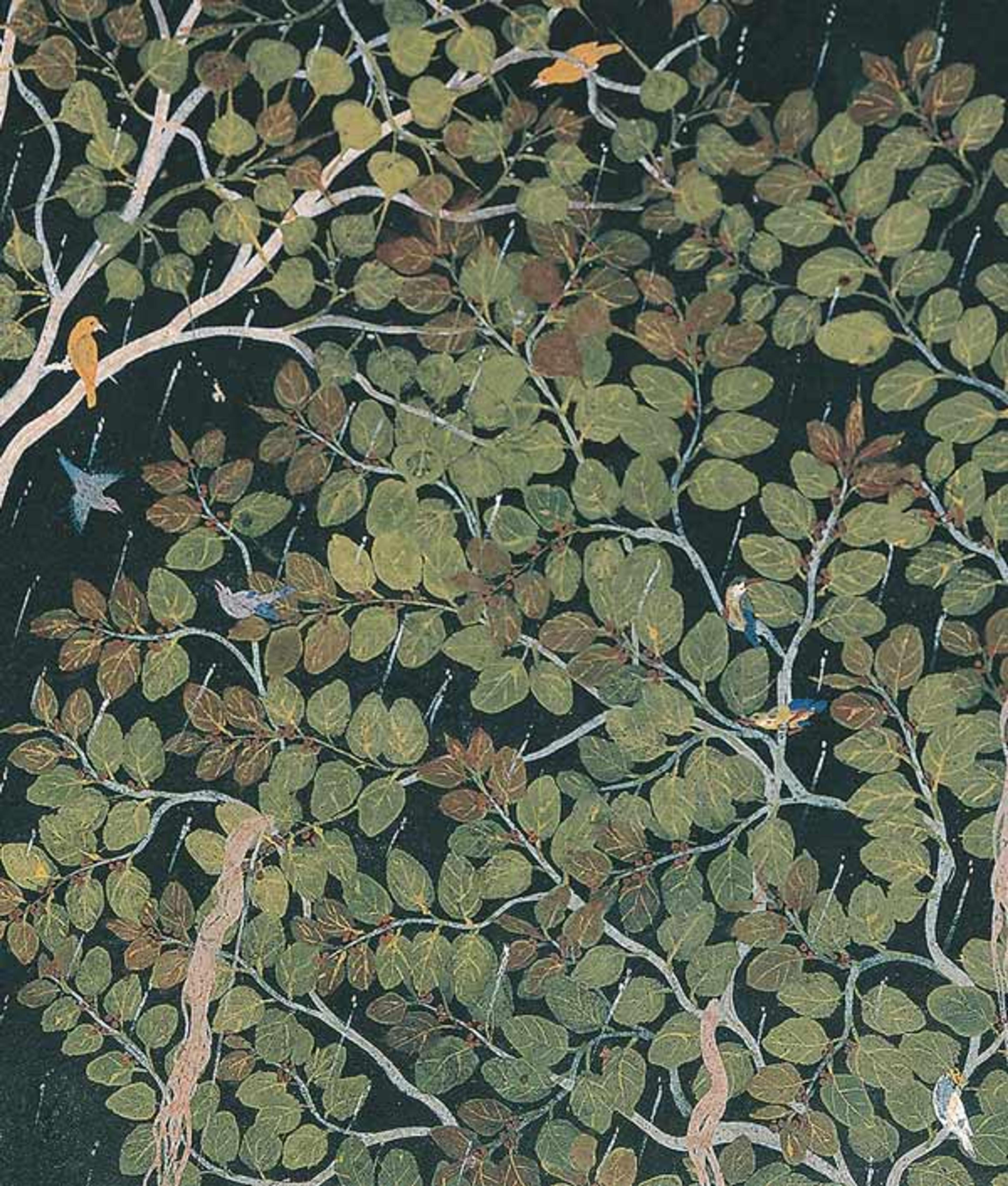

White beads of rain fall from a brooding blue sky, indicating the height of the monsoon season. Below this is a line of trees, including, from left to right, the neem, the peepul, and a member of the Banyan family. Amidst the branches are more than a dozen meticulously painted birds, most of which are either camouflaged or so small that they require a magnifying glass to spot.

Detail view showing more than a dozen varieties of birds

The central figure is clearly the swooping peacock on the right side of the page. Peacocks appear frequently in ragamala paintings, and, in this instance, they are symbolic of unrequited love. In a description of the piece written by art historian Mark Zebrowski, author of the seminal volume Deccani Painting, he suggests that the bottom half of the page would have likely depicted a single woman pining for her lover.

Detail view of the peacock in flight

The imperfect condition of this piece actually allows the viewer to appreciate one of the most remarkable qualities of ragamala paintings: their ability to convey an emotional state of being through brushwork, color, and a nuanced depiction of the environment. Indeed, this focus on emotion (known as rasa) and the powerful impact of color is a key aspect of the raga, whose structure and performance is meant to reflect and evoke particular moods linked to various seasons and times of day. In fact, the word raga is rooted in the Sanskrit word meaning "color."

In this instance, the artist evokes the sensations of anticipation, release, and growth through his articulation of the sky and rain, the foliage, and the animal life woven throughout. It is remarkable that such a range can be experienced even with half the page missing. The artist conveys the Hindu belief in the affinity among all life forms. We can only assume from the precision of the upper portion that the artist regarded nature as lovingly as he did the human and divine figures that would have been depicted below.

The piece is not all about precision, though; the artist is also a master of balancing simplicity with detail. The irregular brushwork at the top half evokes the uncontrolled energy of a storm. Here, the artist chose gesture over exactitude: the streaky paint and asymmetry of the clouds are enough to evoke the season's mood. Meanwhile, the depiction of rain is not illusory, but rather simply suggestive. A small dot illustrates each raindrop, but it is the white lines following them that create the sense of movement and energy throughout. The artist seems more concerned with conveying the sensation of falling and release than with creating a literal rendering of rain. While the foliage is fully articulated, the artist leaves the background ambiguous—a dark, blank expanse, which, based on other similar paintings, we can assume is a hill. The dark color, however, feels equally suggestive of a body of water or the abyss of a black night sky.

These ambiguities reflect the fact that while ragamala paintings certainly conveyed narratives and followed an iconographic structure, it was most important for them to evoke a mood: a sense of place, time, and the emotionality associated with this. For the viewer who knows little of the back story of this medium and cannot read the Sanskrit text at top, the visual rendering is enough of an opening into this time and place. Just as ragas contain endless variations based upon their central arrangement of notes, these paintings leave much to be interpreted. For all their detail, they are fundamentally mysterious works.