Raja ki Chhatri (King's Memorial), Tomb of Mirza Raja Jai Singh I, Burhanpur, 1667. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

«As part of the exhibition Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy, on view through July 26, Paris-based photographer Antonio Martinelli was commissioned by the Met to document the land and remains of former Deccan empires in India. Some of these photographs are displayed in an enlarged format across the exhibition's galleries, while many more are printed in the accompanying catalogue. Martinelli's unique sensibility, as well as his background as an architect, photographer, and well-seasoned visitor to India, provide yet another look into the enchanting world of the Deccan. I recently had the chance to sit down with Martinelli to gain some insight into his creative process as a photographer.»

Julia Rooney: Give me a brief history of your interest in photography, and particularly in photographing India.

Antonio Martinelli: I was born and raised in Venice, and traveled to India for the first time in 1972. On this trip, our minibus was totally robbed—everything was stolen except for my camera, which had been hidden under my seat. Was it a sign? I was already an amateur photographer and photography was my passion, but I had started studying architecture because, at that time, there weren't any photography schools in Italy, particularly in Venice. It was after that first trip to India that I started my photographic career. So it was a combination of photography, architecture, and India that led me to this career. I had very little equipment and a limited amount of film at that time. I later graduated with an architecture degree, in 1979, and my thesis was a project that used photography to explore the history of the City-Temple of Srirangam in South India.

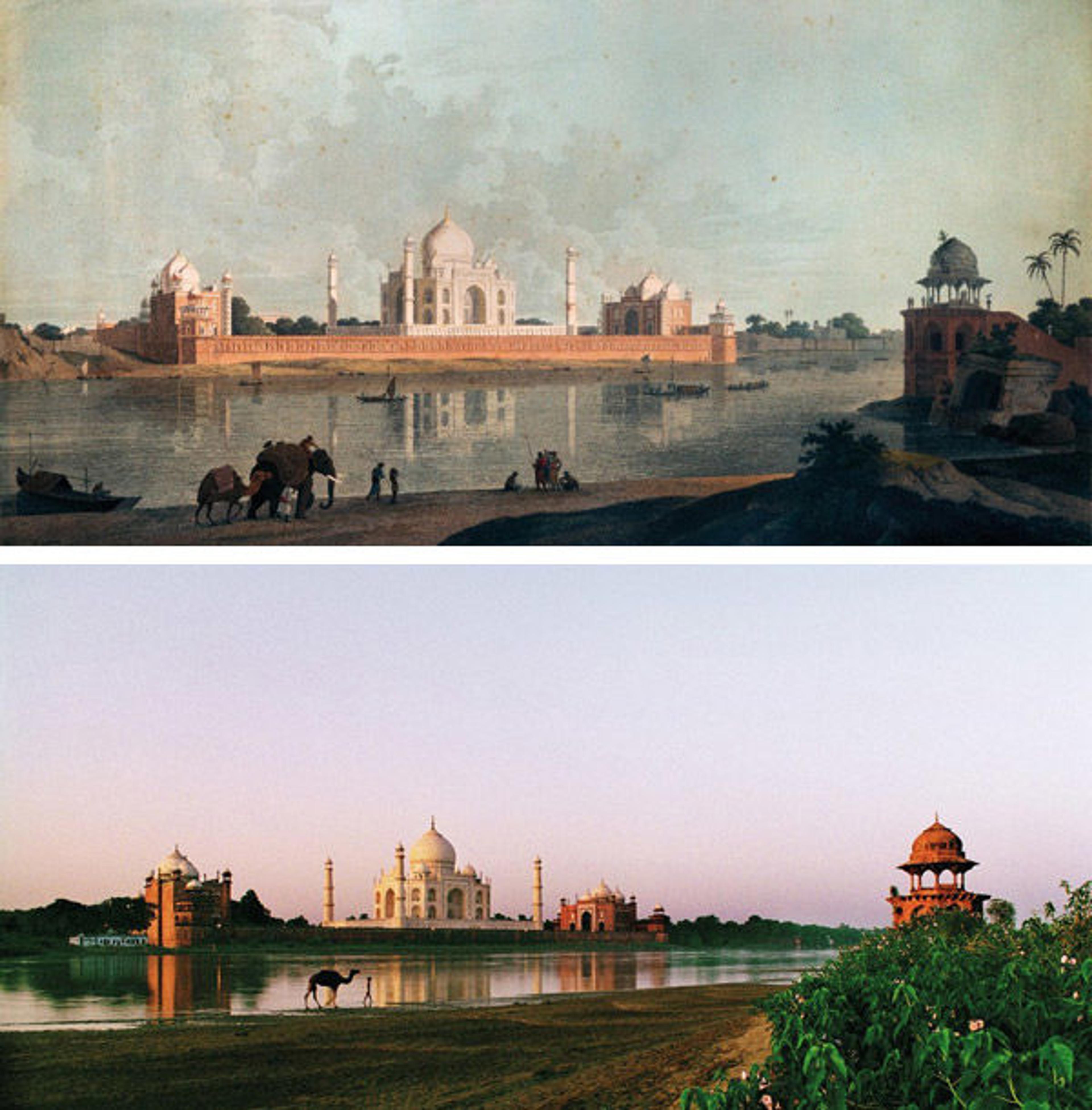

Above, top: The Taje Mahel, Agra, 1801. Aquatint, drawn and engraved by Thomas and William Daniell. The British Library, London; bottom: Taj Mahal, Agra. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

Julia Rooney: Two words that come to mind when I think of your work are "light" and "luck"; they seem to be strong elements in your approach to the photographic medium. Looking at the two photographs above in particular—an aquatint (top) and your own photograph of the same site (bottom)—I wonder how these elements of light and luck function in your work. Are they part of the reason you've chosen photography?

Antonio Martinelli: It is not the reason why I have chosen photography, but definitely these two elements are essential to me during the photographic process. For me, photography means being able to tell a story in one picture; a single photograph should stand on its own and live its own life. Looking at these two pictures, what is interesting about mine compared to the aquatint is that it reveals the truth that has to be told with photography.

A painter can adjust light accordingly to his subject, as can be seen in the Taj Mahal image drawn and engraved by Thomas and William Daniell in January 1789. We know the monument never gets the light that way in the winter since this is the north facade of the Taj. So in order to match the atmosphere, the only moment for me to take the equivalent picture was in the early morning, and that's not the same light—mine is coming from the east while theirs is a sunset light. Still, I'm very respectful of their work and I can forgive creative licenses. These artists did it to give justice to the building, but my medium is very limited compared to what a painter can do. Today you can adjust it a bit if you wish with Photoshop, but at the time I took this photograph, in 1996, that wasn't available. Even if it were, I would not have used that trick.

About the luck factor, to make a good photograph you have to align an interesting viewpoint, good cropping, good light, and perfect exposure. However, there is also the factor that comes into the frame and sometimes makes the picture not only good but also unique: a ray of sunlight during a storm, a bird inside the frame of a window, a person coming out of a gate with a bunch of roses, a dog inside an old interior, etc. This you cannot predict!

Julia Rooney: When does your photographic process start and end? How do you set up a photograph, and what do you do after you've taken that photograph? How do you cull, edit, and crop after taking thousands of images? Also, are you photographing digitally, or are you still using film?

Antonio Martinelli: I've stopped using film. When everybody was moving to digital, I couldn't continue to work with film anymore or I'd be out of business. I'd been using a 35mm camera all my life, even though it's quite unusual for an architectural photographer not to be using large-format cameras. I have adopted this way of working because I find it more flexible and it gives me more possibility of using a range of lenses not available with large-format equipment. I can work quite fast this way, even if I work slowly compared to other photographers. In fact, I am using a small-format camera with the same philosophy of an architectural photographer: putting it on a tripod and framing the view exactly on the camera as it would be on the glass plate. I almost never cut the image afterward—my cut is on the camera, in the first view—and rarely do I adjust the crop. Working with digital photography is just an extension or improvement on what you have learned and done before; it's just a matter of using a new tool.

Dome, Charminar (Four Towers), Hyderabad, 1591. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

Julia Rooney: In thinking about composition, I wonder what your relationship is to abstraction. Some of your images seem to become pure geometric forms. Your sensibility as an architect—this recognition of angles, forms, and light—really comes out. It also makes me wonder what the difference between commissioned and noncommissioned work is for you. Do your criteria differ, and if so, how?

Antonio Martinelli: They are different and they are not. If I'm conceiving a project and don't have the pressure of a commissioned work, I will still have to give myself a structure, a guideline, a shoot list, and then work from that. This is a way not to be so dispersed, because it is easy to get lost. And even if you are working for yourself or for a client, you still have to have time and a budget limit that you have to take into account. So you need to create a framework and try not to go too much off the track.

Then, of course, when you are working on a commission assignment, you have to respect what the wishes of whomever is commissioning you. First you have to deliver the essentials of what they expect, and then you can flourish and you can add your own touches. This doesn't mean that you're not going to provide what they asked for, but rather that it will be your own vision and share your sensibilities.

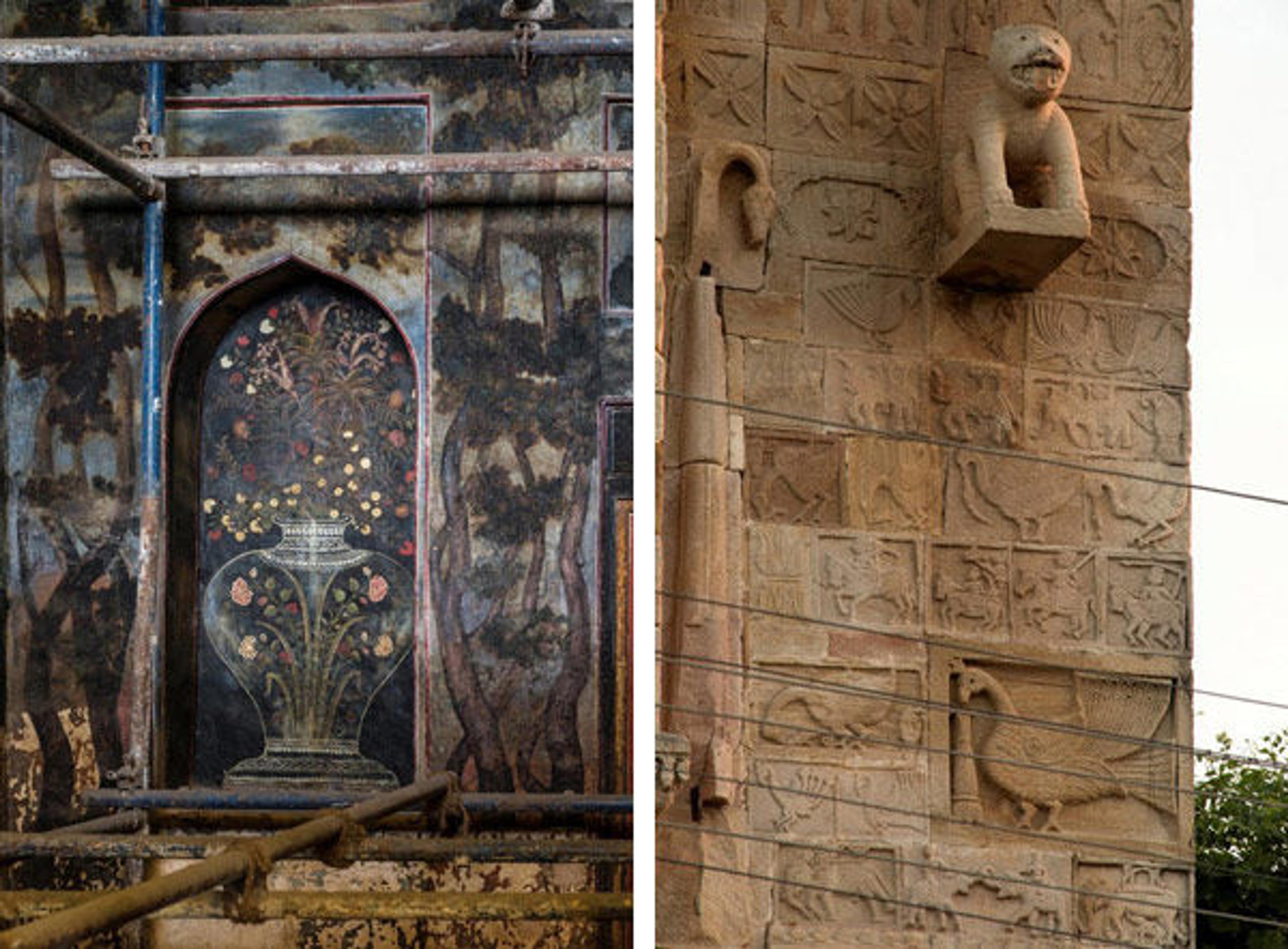

Left: Asar Mahal interior, Bijapur, 1647. Right: Bababagh Gate (detail), Achalpur. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

Julia Rooney: Looking at your photographs, I feel the strongest ones are those that both document the historic object or site before you and then incorporate some contemporary element. You have an eye not only for the architectural facade that is your focus, but also something as mundane as a street sign. This contemporary element is very subtle; you almost miss it. But as a viewer, it puts me between a living, contemporary space and a more voyeuristic one—looking at something else, from another generation entirely.

Antonio Martinelli: Exactly. It's always to show the context and the framework, so it's not an isolated object. We're talking about the environment of the image; it's the relation between the object and the space.

Bababagh Gate, Achalpur. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

Julia Rooney: There's this image (above) of a beautiful monument interspersed with wires, poles, and graffiti. Of course the monument is itself a work of art, but your sensitivity to these elements makes the photograph an entirely new vision of the scene.

Antonio Martinelli: Why should I try to avoid or erase what is there? It is also a way to communicate to the people in charge of protecting the monument, to show there is an encroachment—something disturbing that shouldn't be there.

Julia Rooney: In other photographs, this also gives emotion to the work. In some cases, there's humor involved, while in others, I find it's more about longing, sadness, and nostalgia. You simultaneously integrate and evoke all of these emotions.

Antonio Martinelli: My image of an abandoned chai shop at the entrance of Gavilgarh Fort (below), shows this well. It is an incredibly romantic place where you feel out of time. But, in fact, this chai shop brings you back to the present and at the same time becomes part of the landscape and gives the sense of what reality is in India, which is sometime also a mess, a visual anarchy.

Gavilgarh Fort, 15th–16th century. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

Julia Rooney: On that note, I'd like to discuss how human figures function in your work. I love that there are tiny figures in some photographs, and that the viewer practically misses them. They're so subtle, and yet they bring you back to the contemporary—making you realize that these are real, lived-in places, and not abstract, fictional ones.

Antonio Martinelli: When I started as a young photographer, I always admired the work of Gianni Berengo Gardin, his architecture and cityscapes shoots in which he always incorporates small human elements. He doesn't get too close to them, but he will include them in the landscape. I also try to place a human figure against a piece of architecture or monument in order to show scale and dimension.

Left: Daulatabad Fort, interior. Photography © Antonio Martinelli

Julia Rooney: It also seems to clarify time and space. I think it is similar to the way that nature interacts with these structures in so many of your photographs. There's an incredible fusion and understanding of the natural and the man-made.

Antonio Martinelli: Yes, I'm not suggesting that monuments should only be looked at, but rather that they are lived in by people. There is a relationship there, and people use them daily. You must capture that moment.

Julia Rooney: How was the experience of returning to India for this project?

Antonio Martinelli: I'm so pleased that Navina Haidar and Marika Sardar gave me this opportunity to express myself—to do something again with India, a country which has given me so much. So I feel I must give something back in return, a tribute. I would like to continue doing projects there because it is my favorite artistic playground. But although I'd also like to work in other countries, India is a real passion for me. Every time I go, I say how lucky I am to be able to do something that transports me in a voyage through time and space.

Related Links

Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy, on view April 20–July 26, 2015

View a slideshow of images from Antonio Martinelli's travels throughout the Deccan empires.

Watch Friday Focus Conversation—In the Footsteps of India's Deccan Sultans: A Photographic Journey on MetMedia.