Taking a Closer Look at the Amati "King" Cello

Fig. 1. Andrea Amati (Italian, ca. 1505–1578). Violoncello, "The King" (detail), mid-16th century. National Music Museum, Vermillion, South Dakota, Witten-Rawlins Collection, 1984 (NMM 3351)

«Decorated instruments in the violin family such as Andrea Amati's "King" cello were usually made in sets or consorts, and were intended as diplomatic gifts to celebrate important state occasions. Because of this, the decorated Amati instruments were limited in number and are now extremely rare to see outside of museums and private collections. Luckily for visitors to the Met, the "King" cello, the world's oldest surviving cello, is now on view through September 8, 2015, in The André Mertens Galleries for Musical Instruments, on loan from the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota.»

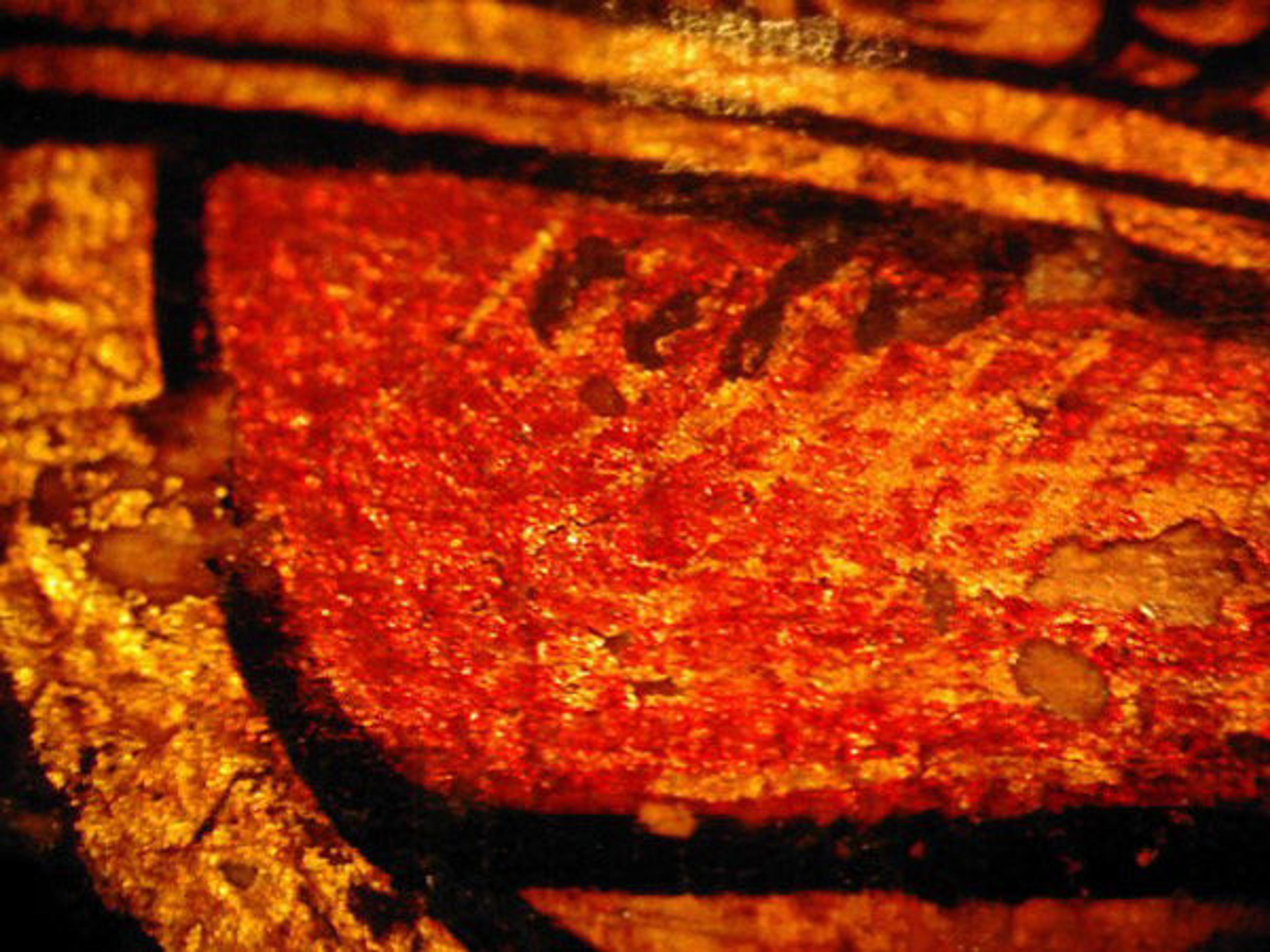

The violin family was the epitome of fashion during the 1500s, and its music, decorations, armorials, and impresa carried political messages that gave advantage to the French royal dynasties. All of the instruments that once belonged to the French royal family carry as a primary motif the fleur-de-lys—the signature of the Valois kings and their right to rule through the Capetian lineage (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. A fleur-de-lys painted on the cello's body. All photos courtesy of the National Music Museum

The "King" cello is painted in oil in the style of Limoges porcelain, which includes colored fields outlined with thin, black lines together with colored, transparent overglazing of metal leaf and associated line drawing. The designs were laid down using pounce pattern technique, which is evident when viewed under infrared light (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The cello's paint layers as seen under infrared light

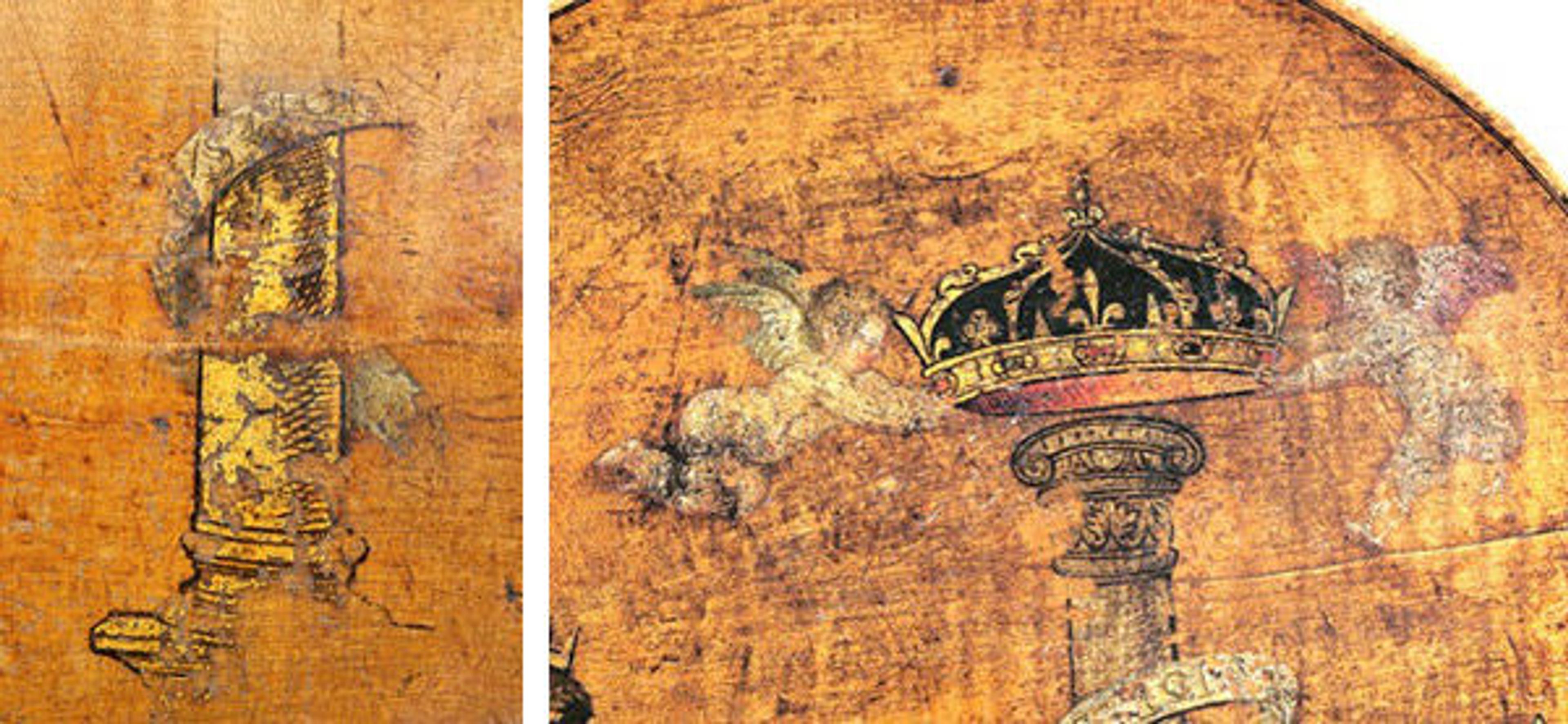

The collar surrounding the escutcheon in the center of the instrument's back represents the collar of the Order of Saint Michael, created by Louis XI in 1469. The order was limited to sixteen members, of which the French king was the grand master, who originally congregated in the abbey of Saint Michel in Normandy, but were later transferred by Henry II to the Saint Chapelle of the Castle of Vincennes in Paris, the royal residence of Catherine de Medici and Charles IX.

The collar of the order consists of cockle shells, carried by pilgrims to the abbey as a symbol of their piety and their pilgrimage. These are interlaced by the lacs d'amour, or love knots, that stand for indissoluble friendship. From the collar, a medallion is suspended depicting Saint Michael slaying the dragon (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Symbols of the Order of Saint Michael found on the instrument's body

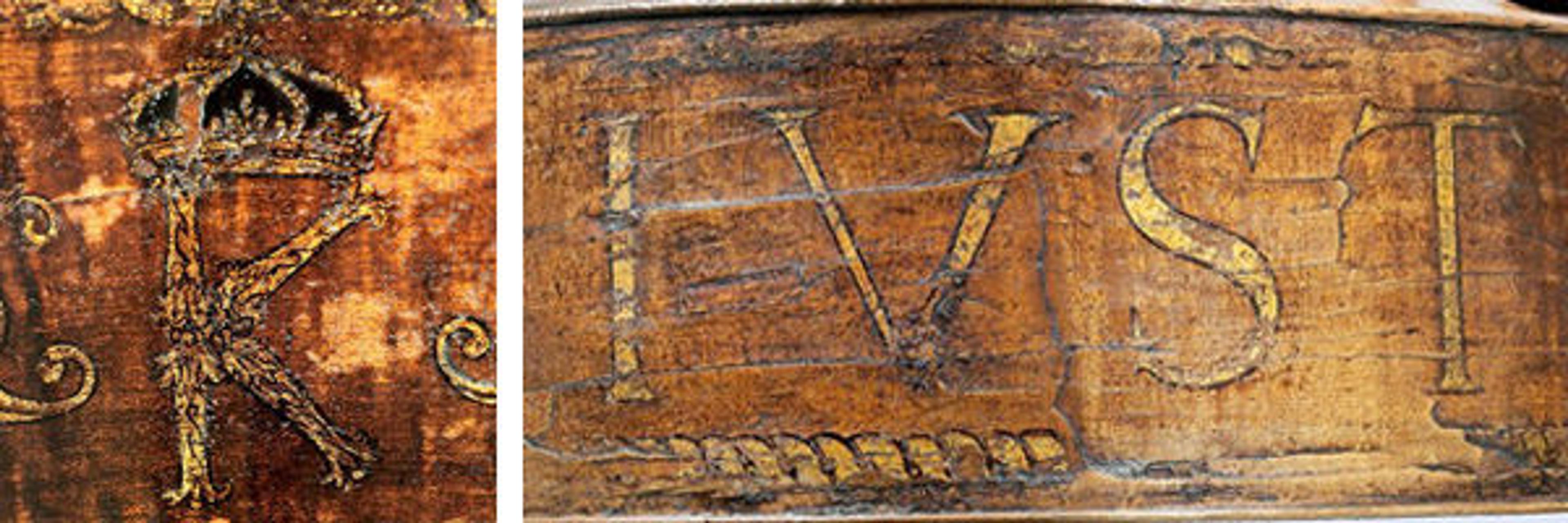

The flanking figures of Piety—now largely abraded, except for the feet—and the figure of Justice support the armorial. The impresa Pieta et Justicia that we see on the cello ribs and column garlands was suggested by Jacques Amyot as a suitable motto for Charles IX, and is found on the coins, books, and regalia of his reign.

This motto running around the rib garland reads Pietate et Iustitia, but the column garlands are spelled differently, Pietate et Justicia (fig. 5, right). The ribs at the waist of the cello carry a letter "K" surmounted by a closed royal crown (fig. 5, left). The "K"—which stands for Charles (Karolus) and for Katherine—is flanked by floral motifs that are not repeated elsewhere on the instrument.

Fig. 5. Lettering found across the cello's ribs

The scroll, which is original, is also decorated with lines of gold leaf and floral motifs of a different kind, which seem to have been copied after typographical ornaments of the sixteenth century (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The scroll is adorned with floral motifs featuring lines of gold leaf

The figure of Justice, the only figure now visible on the instrument, is portrayed in a very strange way (fig. 1). The figure represents rigorous justice and therefore should be looking up to God with her sword held high and unconstrained. The unorthodox form found here, with Justice gazing down, is especially poignant because it indicates the God-like power of the Valois kings, and may allude to the considerable part that Charles IX played in the injustices of the Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre of Protestants in August of 1572.

The columns of Charles's devices are notable, one being gold and the other silver. The straightened columns seen on the "King" cello were introduced in 1567, and were also used for the entry into Paris of Charles IX and his queen in 1572. For this event, the design scheme of the devices was so significantly altered that it was necessary for the merchants of Paris to remake the gifts that they had intended for the long-delayed formal entry of 1563.

Fig. 7. Detail view of columns and putti found on the instrument's back

The columns are painted in perspective and are topped by flying putti seen in the act of placing closed imperial crowns upon them (fig. 7). Both Francesco Primaticcio and the Cremonese painter Giulio Campi produced similar designs, and it is notable that the decorated instruments of Charles IX are representative of different hands, techniques, and dates of production, whilst the Amati instruments themselves are sometimes older and sometimes contemporary with their paintings.

Left: Fig. 8. One of four filled holes that previously held bosses and rings

Also visible on the back of the instrument are four filled holes that once held bosses and rings which enabled the costumed player to hold the instrument securely during court ballets of the sixteenth century (fig. 8). These can be seen on other decorated Amati violins.

The cello's armorials and gold leaf, though worn, have significance beyond being just an artistic gem, as they are the visual key to a romance of wonders and a wasteland of horrors—from the still-unsurpassed splendor of the court ballets of Catherine de Medici, to the carnage of the Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre and the murderous bloody reign of the Valois princes during the French Wars of Religion. This is not the cello's only significance; one must remember that the "King" was not a singular invention, but rather a member of a larger family of instruments of fixed measurements related together by profound mathematical, geometrical, and acoustical relationships of size and tone, which gave the set the ability to perform, in unison, some of the world's first orchestral music for bowed strings.

Andrew Dipper

Andrew Dipper is a consultant conservator of the Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments.