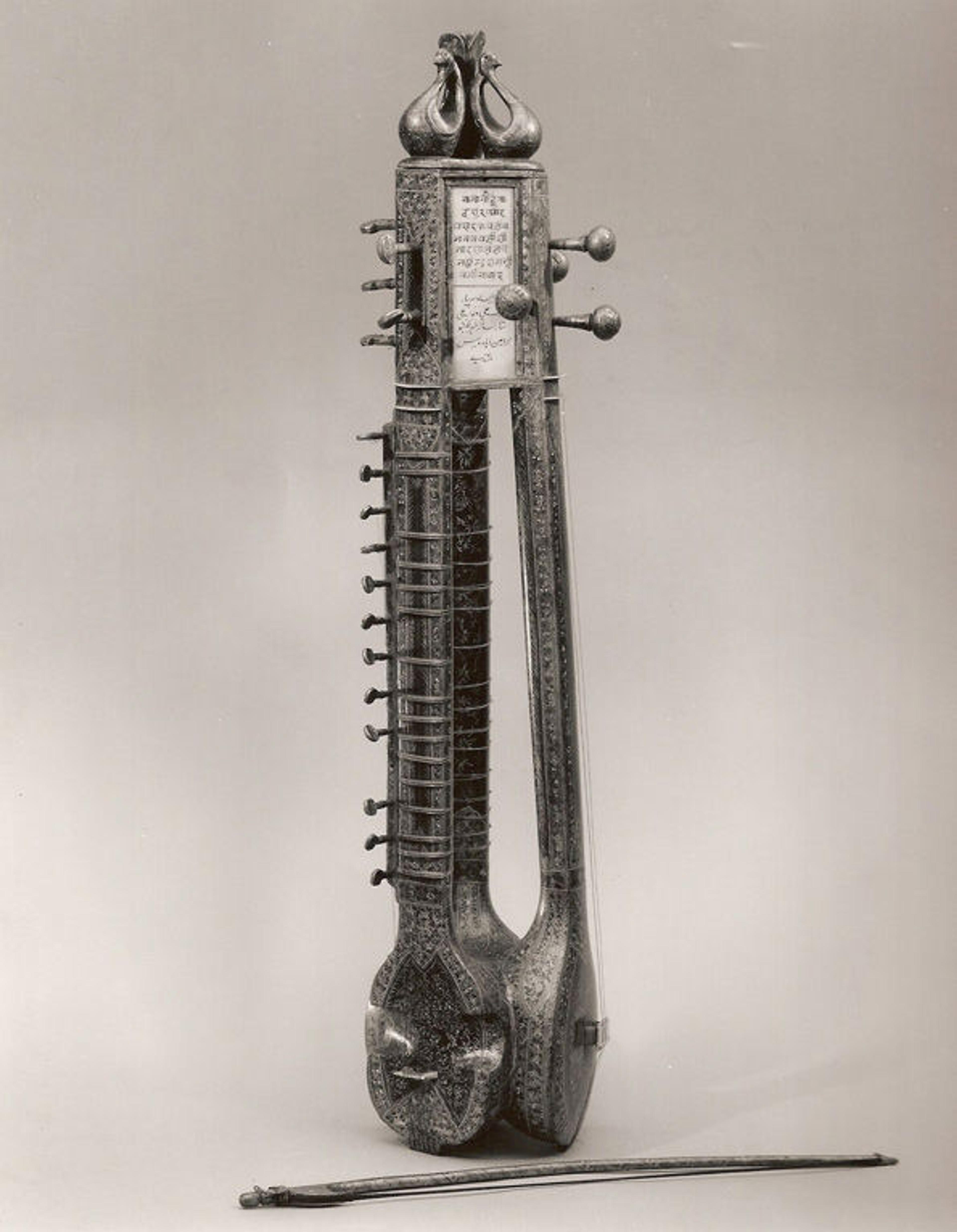

Sūr Pyār (Compound Sitār, Tāmbūra, Esrāj). India, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, late 19th century. Gourd, wood, polychrome, steel and gut strings, ivory, metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.1313)

«The sūr pyār is a novelty instrument comprising three different musical instruments—tāmbūra, esrāj, and sitār—joined together at the base and peg box. Each separate component provides a distinct function in North Indian classical music: the tāmbūra is present in nearly every concert or recording, providing a constant drone in the background that serves as a tonal reference for the melodic instruments; the esrāj is very similar to other bowed instruments from North India, like the sarangī, in its ability to mimic the human voice, and is often used as accompaniment to a vocalist or as a solo instrument; and the sitār—perhaps the most iconic musical instrument of India thanks to Pandit Ravi Shankar—is a solo melodic instrument that is fretted and plucked with a plectrum, or mizrāb, attached to the musician's fingertip.»

Coined the "sūr pyār" ("lovely sound") by its inventors, Ashraf Ali and Nawab Ali, this object demonstrates the innovation of North Indian instrument making in the nineteenth century. The instrument could not have been very popular at its inception, since there are very few references to it in North Indian music history and only two known instruments like these remain in musical instrument collections throughout the world. However, it shows that instrument makers were experimenting and trying to reach new markets in nineteenth-century Lucknow.

Labels found on the instrument's three sides are written in English, Urdu, and Hindi, respectively; however, they do not provide identical information. After translating the different passages, I discovered the address of Ashraf Ali's shop to be in the Aminabad market in Bhusa Mandi. After the First War of Independence, or "Sepoy Mutiny of 1857" as the British call it, artists and artisans left the Chowk area of the city center and relocated their shops to Aminabad. Prior to 1857, according to historians of Lucknow, instrument shops would have been located in Chowk—not Aminabad. This helps to confirm that the instrument was made after 1857.

The presence of the three languages on a single instrument points to the multicultural cosmopolitanism of Lucknow at the time. In the second half of the nineteenth century, instrument makers realized that readers of Hindi, Urdu, and English would all be interested in these types of instruments, and, by extension, the Hindustani classical-music traditions associated with them.

The tāmbūra and sitār are both a bit smaller than they would normally be on instruments of this time period, while the esrāj has more or less the appropriate dimensions. This leaves open for debate how each of these instruments might have sounded, or whether or not they would have functioned well in popular music genres of the time. It is likely that the sūr pyār did not become popular primarily for acoustic considerations. Those limitations aside, however, it is a beautiful instrument with a rich provenance pointing to a specific family of North Indian luthiers, which is quite rare for nineteenth-century instruments that were acquired outside of Europe and North America.

Please join us on April 2 for our next gallery concert, which will feature a concert of North Indian music performed by Abhik Mukherjee, sitār, and Ranendra Das, tablā. To whet your appetites prior to Wednesday's concert, enjoy an example of North Indian sitār playing from a 2013 performance at the Museum that featured K.V. Mahabala playing a drut tintāl composition in Raag Hamir, accompanied by Samir Chatterjee on tablā and Benjamin Stewart on tāmbūra.