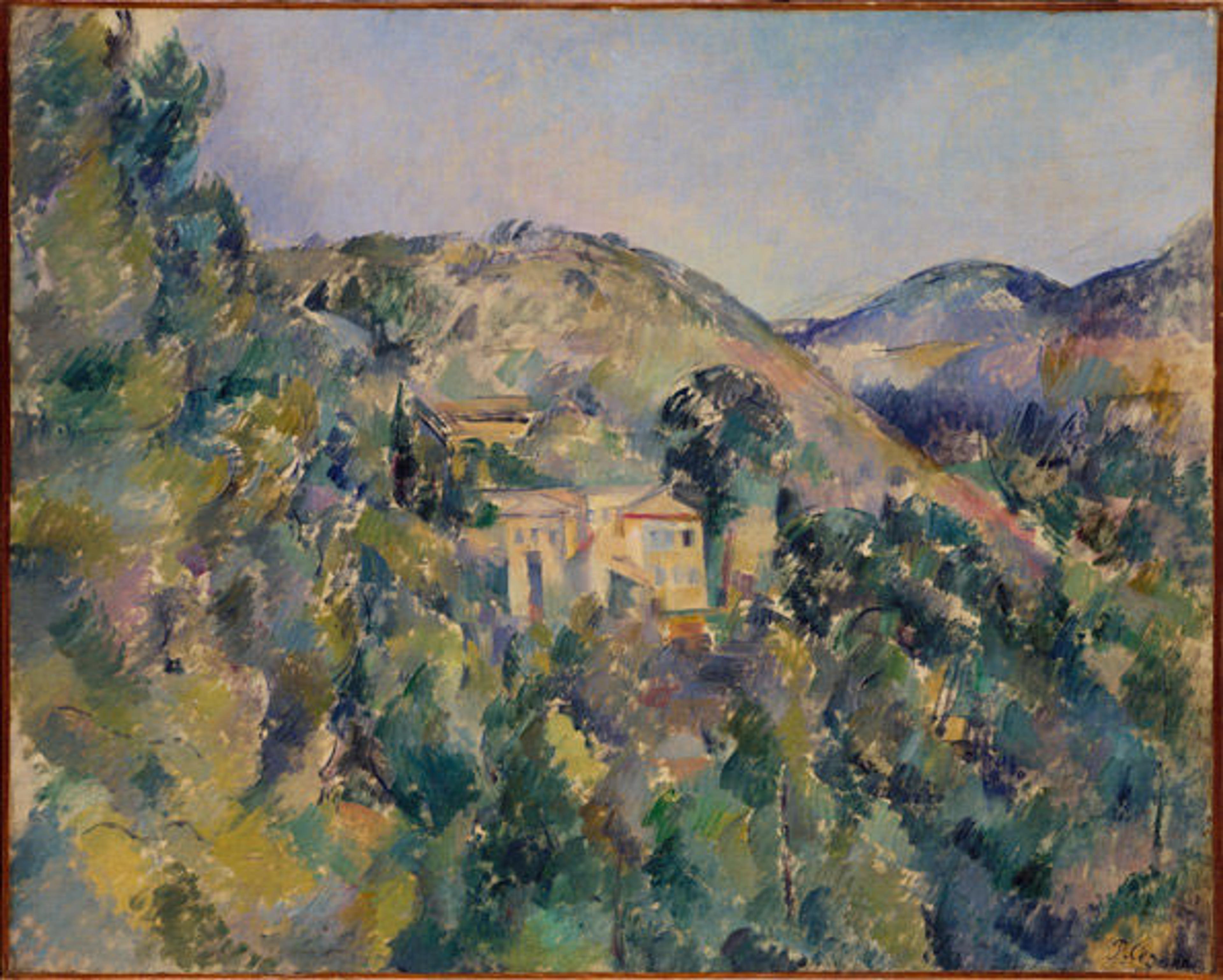

Paul Cézanne (French, 1839–1906). View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph, late 1880s. Oil on canvas; 25 5/8 x 32 in. (65.1 x 81.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1913 (13.66)

«One hundred years ago this weekend, on March 17, 1913, The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired its first painting by the French Post-Impressionist master Paul Cézanne. The Museum purchased Cézanne's View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph at the groundbreaking International Exhibition of Modern Art, popularly known as the Armory Show.»

The day before the exhibition's opening ceremony, the Chicago Daily Tribune proclaimed:

From All Over the World the "Insurgents" Have Gathered in New York—the Cubists, the Futurists, the Post-Impressionists—All with Their Own Pet Ideas. It Promises to Be Worth Going Miles and Miles to See—and Hear.[1]

Over the next four weeks, the exhibition gave the city an international feel that some compared to that of world's fairs. Tens of thousands of visitors came to view and judge for themselves the merits of the modern works on display, many of which had never before been seen by a mass audience.

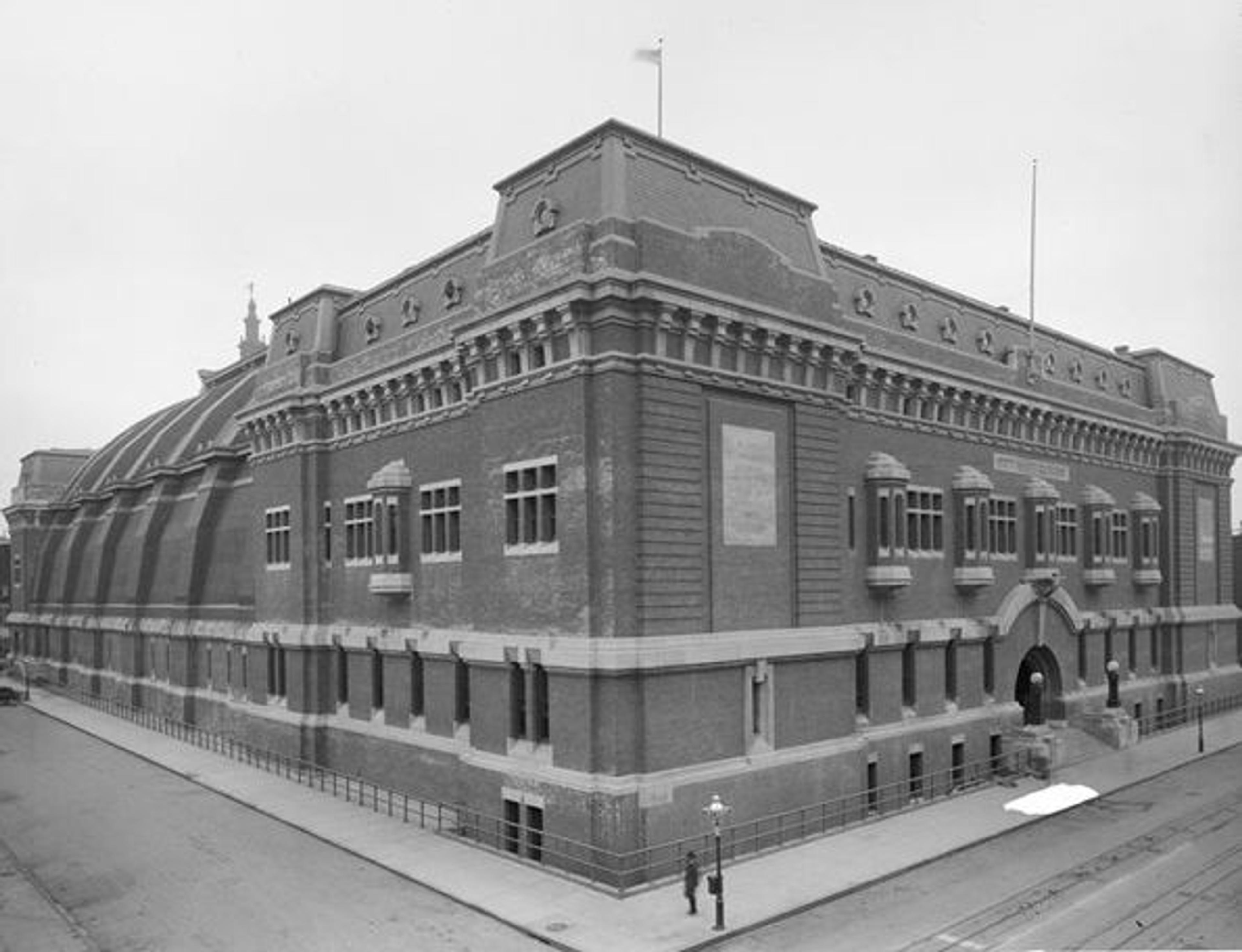

Wurts Brothers. 69th Regiment Armory building on Lexington Avenue between East 25th and 26th Streets, ca. 1905. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York

The origins of the Armory Show date to 1911, when a group of American artists—disgruntled with what they viewed as the conservative taste of organizations such as the National Academy of Design—founded the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. According to Walter Kuhn, secretary of the association and one of its principal founders, the group was to be "a big broad liberal organization embracing every kind of art, even those which I do not like, one that will interest the public."[2] With this goal in mind, Kuhn and his associates spent the year 1912 gathering works of European and American art for the first large-scale modern art exhibition to be held in the United States. By September, the group had leased the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue between East 25th and 26th Streets, and Kuhn proudly reported that the aggregate value of artworks that the group was going to import would exceed $200,000.[3]

On the evening of February 17, 1913, the first visitors to the Armory were able to view over one thousand works of art displayed in a space subdivided with burlap partitions into galleries. John Quinn, legal advisor to and major supporter of the exhibition's organizers, spoke at the opening:

The members of this association have shown you that American artists—young American artists, that is—do not dread, and have no need to dread, the ideas or the culture of Europe. They believe that in the domain of art only the best should rule. This exhibition will be epoch-making in the history of American art. To-night will be a red letter night in the history not only of American but of all modern art.[4]

Arthur B. Davies, president of the association and an artist whose work was included in the show, wrote in a brief preface to the exhibition catalogue:

In getting together the works of the European moderns, the society has embarked on no propaganda. It proposes to enter on no controversy with any institution. Its sole object is to put the paintings, sculptures and so on, on exhibition so that the intelligent may judge for themselves by themselves.[5]

Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York, 1913. Walt Kuhn, Kuhn family papers, and Armory Show records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

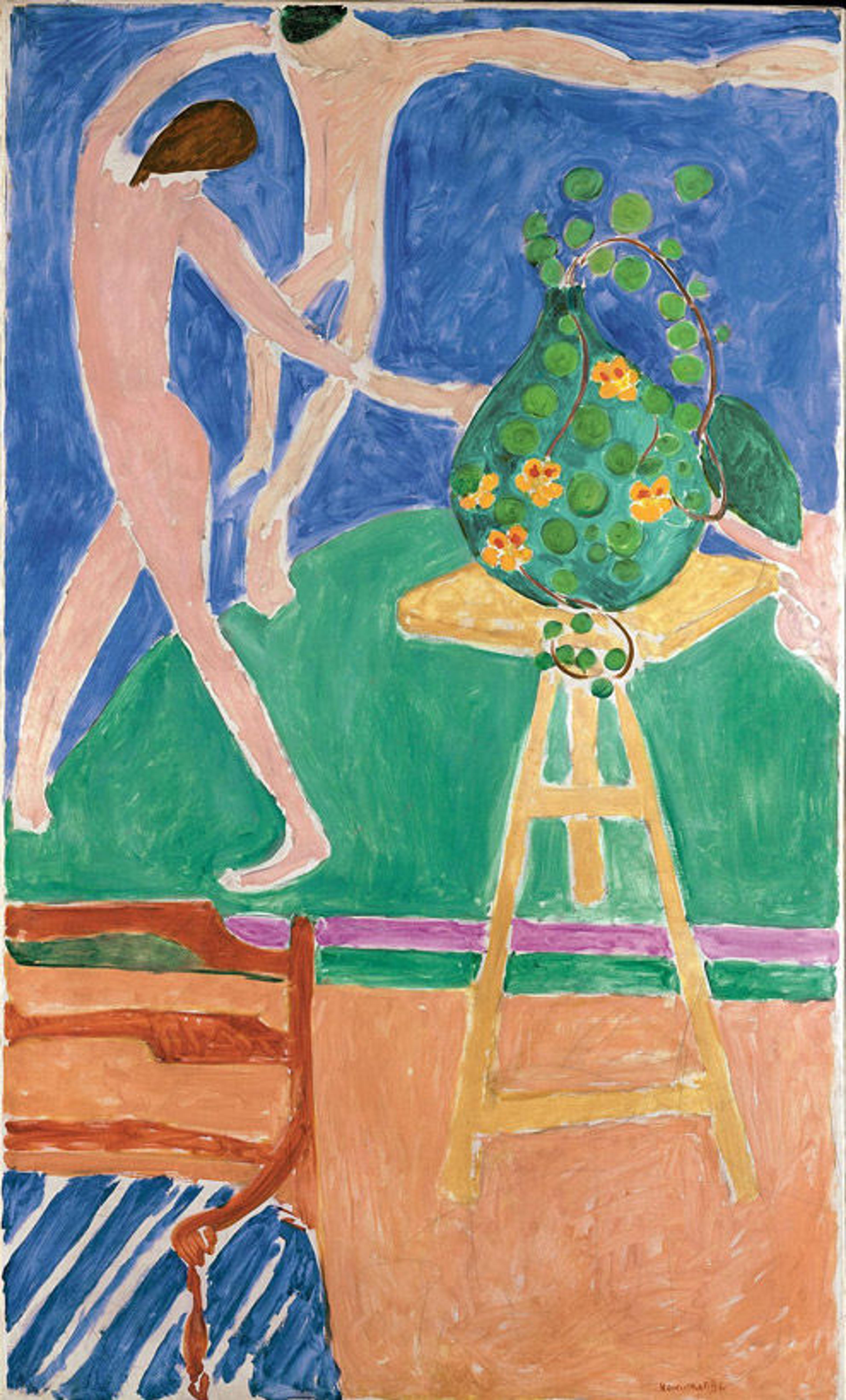

Chronologically, the exhibition began with the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres—a neoclassicist respected by the modernists—and progressed through the rest of the nineteenth century, finishing with works by a selection of early twentieth-century artists. Among the more prominent European artists represented were Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Henri Matisse, Odilon Redon, and Pablo Picasso. Among the American artists were Robert Henri, William Glackens, George Bellows, James McNeill Whistler, Mary Stevenson Cassatt, and Patrick Henry Bruce.

This work by Matisse was among those displayed at the Armory Show. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954). Nasturtiums with the Painting "Dance" I, 1912. Oil on canvas; 75 1/2 x 45 3/8 in. (191.8 x 115.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982 (1984.433.16). © 2012 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Reviews of the show were rarely neutral. The New York Tribune, for instance, described several artworks in the exhibition as "some of the most stupidly ugly pictures in the world," but also acknowledged that there was nothing subversive about them.[6] In a subsequent article, the Tribune wrote:

Let us ignore for a moment the point as to whether this or that exhibit is good or bad. The important thing is that it is not a colorless, neutral affair, but in one way or another sharply asserts itself. The worst of all exhibitions is that one which leaves us bored and indifferent. We ought to be doubly grateful, therefore, for one which compels the public to "sit up and take notice" if it does nothing else.[7]

The Christian Science Monitor noted the extent to which visitors to the exhibition found it enlightening, publishing the following anecdote:

A woman robed in a Paris gown, which must have been of the Futurist school—certainly not of the Cubist—stood in front of one of Matisse's arrangements. Unable to express her admiration in words, she took a few steps of the dance. "It is motion," she said, "the poetry of motion."[8]

In the initial decades after its founding, The Metropolitan Museum of Art had been reluctant to acquire contemporary art, but at the 1913 Armory Show, paintings curator Bryson Burroughs decided to try to purchase Cézanne's View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph for the Museum. Painted in the late 1880s, the image is a view of a hill, the Colline des Pauvres, on the road between Aix-en-Provence and the village of Le Tholonet. Writing to Museum Trustee John G. Johnson, Burroughs made his argument:

The asking price, $8,000., is high but fifteen per cent duty will be deducted from that making the price to the Museum $6,800 and I think that that amount could be shaved somewhat. It might be bought, I should think, for $6000. Or a little over, and at this price would be very reasonable. It is a very good work, painted in the early 90's. …

It would be a popular purchase with a large number of our public and would make valuable friends for the museum.[9]

Responding to Burroughs's letter, Johnson wrote:

Whilst the Impressionist Art does not appeal very strongly to me, I recognize that this is a mere matter of individual taste, and that it does appeal very strongly to very many connoisseurs of the highest taste and best judgment.

I think it well, also, for any Museum to have represented on its walls, examples, as far as possible, of everyone who stands for something in art. Cezanne does thus stand.[10]

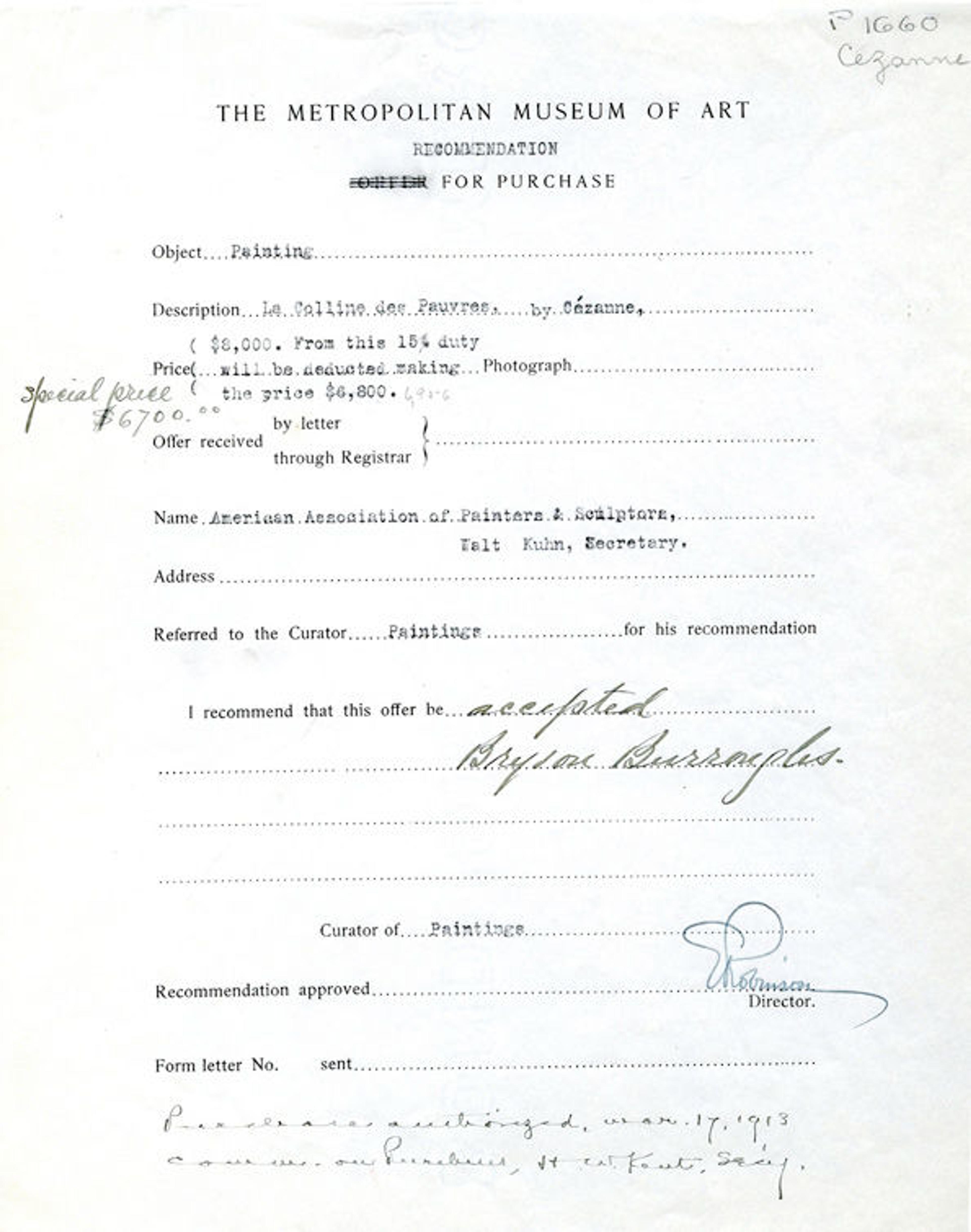

The Trustees authorized Burroughs's purchase of the work on March 17, 1913, approving the following internal document in recommendation of the acquisition.

Recommendation for the Purchase of Cézanne's La Colline des Pauvres (now identified as View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph). Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

The initial asking price of $8,000 (approximately $185,000 today) was eventually reduced to $6,700 (approximately $155,000 today), and the Museum's purchasing committee approved of the acquisition. Even at its reduced price, Cézanne's View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph was the most expensive painting purchased at the Armory Show; another Cézanne—Femme au Chapelet, which was priced at $48,600—found no buyer. Today, Cézanne's View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph is displayed in gallery 825 at the Museum, alongside other, more recently acquired works by the artist.

Footnotes

[1] Harriet Monroe, "Bedlam in Art," Chicago Daily Tribune, February 16, 1913, G5.

[2] Milton W. Brown, "Walt Kuhn's Armory Show," Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 27, No.2, 1987, 5.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] "2,000 at Art Exhibit," New York Tribune, February 18, 1913, 6.

[5] "Art Productions of Many Sorts Shown in International Exhibition," The Christian Science Monitor, February 21, 1913, 15.

[6] "The 'Ism' Exhibition," New York Tribune, February 17, 1913, 7.

[7] "Art—and the Art of Thinking," New York Tribune, March 2, 1913, 8.

[8] "Art Productions of Many Sorts Shown in International Exhibition," The Christian Science Monitor, February 21, 1913, 15.

[9] Bryson Burroughs, letter to John G. Johnson, March 6, 1913.

[10] John G. Johnson, letter to Bryson Burroughs, March 7, 1913.