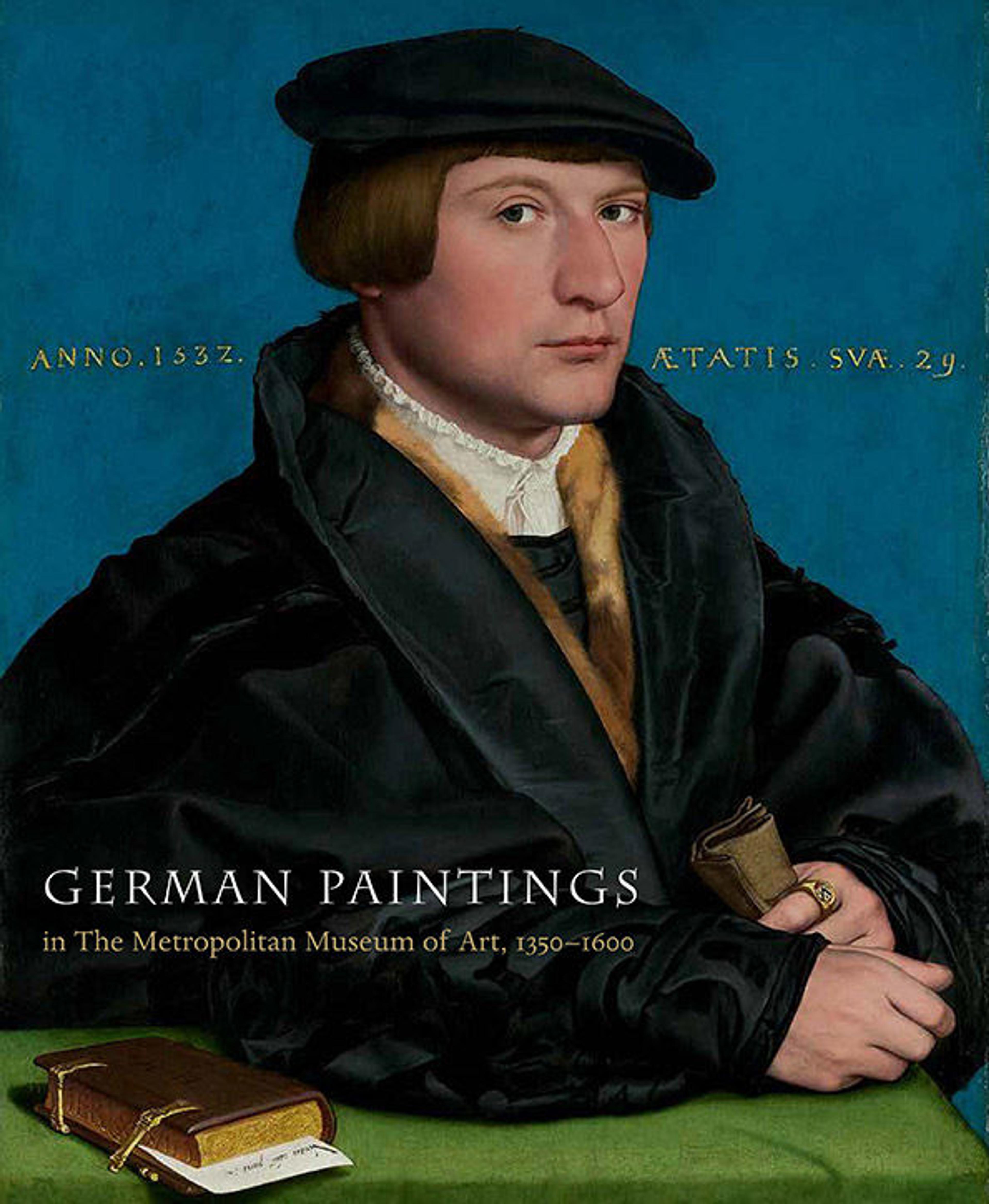

German Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1350–1600, byBy Maryan W. Ainsworth and Joshua P. Waterman, features 315 illustrations in full color and is available in The Met Store.

«Just in time to celebrate the opening of the New European Paintings Galleries, Curator Maryan Ainsworth has coauthored a comprehensive guide to the Met's German paintings. The collection, which includes pictures made in the German-speaking lands (including Austria and Switzerland) from 1350 to 1600, constitutes the largest and most comprehensive group in an American museum today. Comprising major examples by the towering figures of the German Renaissance—Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Hans Holbein the Younger—and many by lesser masters, the collection has grown slowly but steadily from the first major acquisitions in 1871 to the most recent in 2011; it now numbers seventy-two works, presented here in sixty-three entries.»

Below is a sampling of the included works, with excerpts by Joshua Waterman and Ainsworth, whose previous catalogue of the 2012 exhibition Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart's Renaissance, the Complete Works received the prestigious Alfred H. Barr Jr. Award for "an especially distinguished catalogue in the history of art."

Hans Holbein the Younger (Augsburg 1497/98–1543 London). Benedikt von Hertenstein, 1517. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, aided by subscribers, 1906 (06.1038)

When this portrait was painted, Holbein was only about twenty years old and had not yet been admitted into the Painters' Guild in Basel, which he paid to join in 1519. . . . Viewed straight on, Hertenstein appears noticeably broader than he perhaps should, with an oversized left arm and hand. But, as we pass from left to right before the painting, he assumes more natural proportions and seems to project in a realistic manner out of his space into ours. As he engages us with his glance and we reach an angle of forty-five degrees opposite his image, we gradually experience the full force of Hertenstein's corporeal presence. The inscription becomes more prominent, and the authorship of the painting is featured. Holbein's striking effect of verisimilitude, in which the ideal image of the man is recognized only "in passing," calls attention to the transience of life—both Hertenstein's and our own.

Lucas Cranach the Younger (Wittenberg 1515–1586 Wittenberg). Nymph of the Spring, ca. 1545–50. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.136)

This small, astonishingly well-preserved painting shows a nude woman reclining on the grassy bank of a river, near a spring that issues from a rock formation. Looking toward the viewer, she identifies herself and offers a word of caution through the first-person Latin inscription at the upper right: "I, nymph of the sacred spring, am resting; do not disturb my sleep." The scene's open eroticism is heightened by the nymph's sultry, half-closed eyes; the red tinge of her cheeks, buttocks, elbows, knees, and feet; the transparent veil that meanders from head to foot, as if to guide the viewer's gaze along her body; and the bundled red dress, which evokes the thought of her disrobing. A bow and quiver hang in a nearby tree, signaling that the nymph belongs to the entourage of the huntress goddess Diana. A green parrot perched on the bow and two rock partridges in the grass probably serve as symbols of the Luxuria (lust) that is embodied by the nymph and called forth in the male viewer.

Hans Süss von Kulmbach (?Kulmbach ca. 1485–1522 Nuremberg). Portrait of a Young Man; (verso) Girl Making a Garland, ca. 1508. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.21)

This small, double-sided panel bears a portrait of a man on one side and a depiction of a girl making a garland on the reverse. . . . This is among the relatively few extant early sixteenth-century panels that join a portrait with an emblematic or allegorical subject on the verso. . . . Wearing a dancing dress, the girl is presented as a young maiden, her loose, flowing hair adorned with a double string of pearls symbolic of her chastity. Rather than a portrait, she is a female type, symbolizing a lover or prospective bride. Although the wreath of flowers was traditionally worn by women at festivals and tournaments, it was also commonly donned without a special event in mind by girls in southern Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Most important for our painting was the wreath worn by the bride as a sign of her virginity on her wedding day, when it would be taken from her with certain rites and replaced with a bonnet. The cat has many connotations in the art of this period, but the most likely one here is that suggested by Sigrid and Lothar Dittrich: a symbol of the respectable, constant love for the man who appears on the other side of the panel.

Related Link

The Met Store