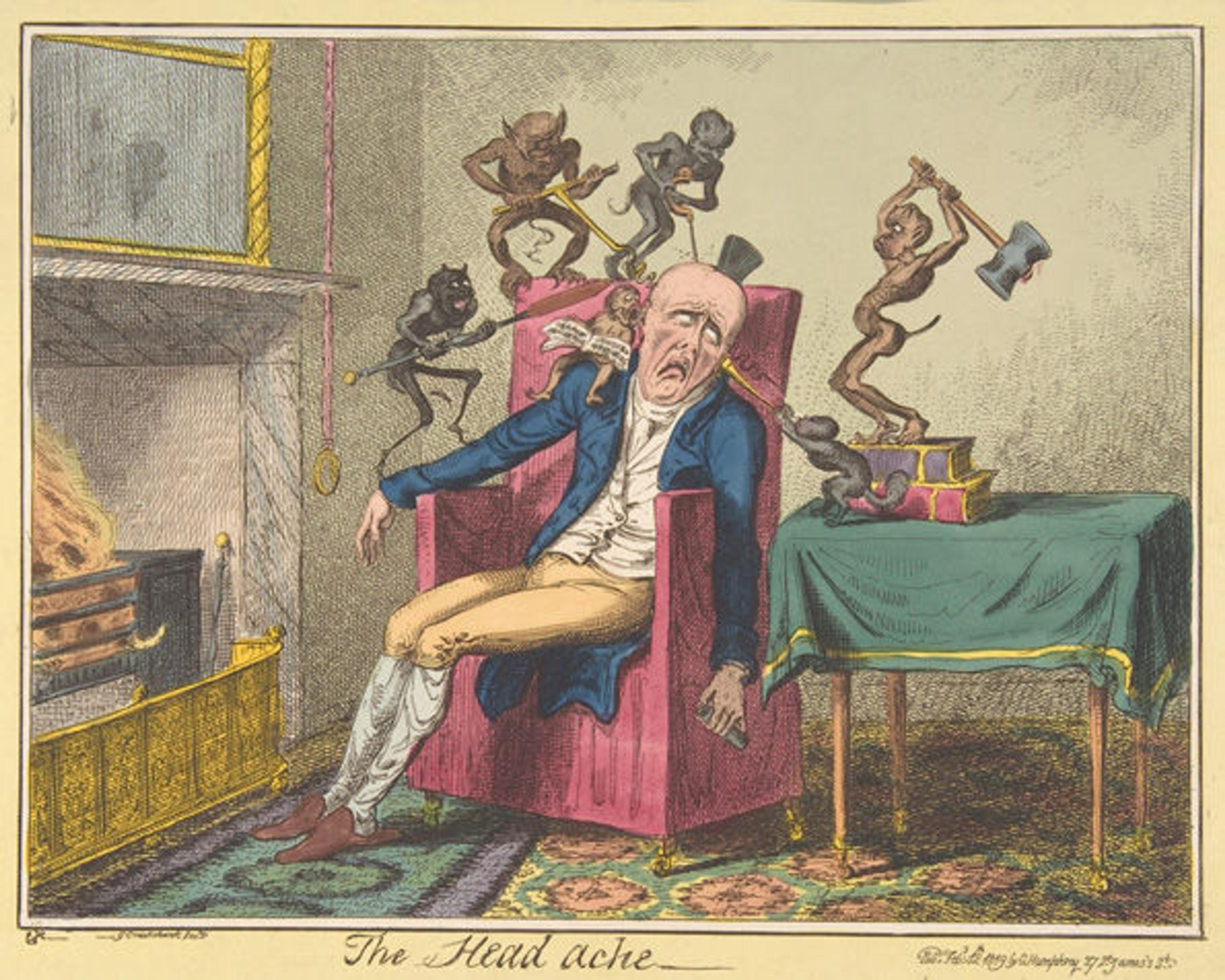

«Caricatures and satires are generally created to comment on specific events or moments in history. The Headache, Enrique Chagoya's print of President Obama, for example, reminds us of the strident debates that took place more than a year ago about changes to the U.S. healthcare system. Chagoya based his image on a nineteenth-century print by George Cruikshank entitled The Head Ache that illustrates a man attacked by hammering and drilling demons who are the source of his woes.»

Enrique Chagoya (American, b. Mexico 1953). The Headache, A Print after George Cruikshank, 2010. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Stewart S. MacDermott Fund, 2010 (2010.285)

George Cruikshank (British, 1792–1878). The Head Ache, February 12, 1819. After Captain Frederick Marryat (British, 1792–1848). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1970 (1970.541.251)

Simply by substituting Obama's face for that of the original beleaguered sufferer, Chagoya has given the image a contemporary subject to which we can relate and even chuckle over as we remember the moment to which it refers. Understanding the meaning of works that were created more than two hundred or even three hundred years ago is a bit tougher. We have to dig through the historical record to reconstruct not only the event to which a print refers but also to figure out what people thought about it at the time.

The Last Papal Assembly (La dernière assemblée papale), June 1796. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1962 (62.520.298)

In some cases, inscriptions can help us pinpoint these moments. For instance, an early collector added dates to what is now the Met's assemblage of French Revolution caricatures. The "June 1796" date on The Last Papal Assembly helps us figure out that the work refers to the period following the Treaty of Tolentino, in which Napoleon confiscated papal territories and emptied the papal treasury. This hilarious image of the Pope and cardinals up to their ankles in tears now makes sense: they're crying over lost wealth. The already funny image is even funnier when we know the historical context.

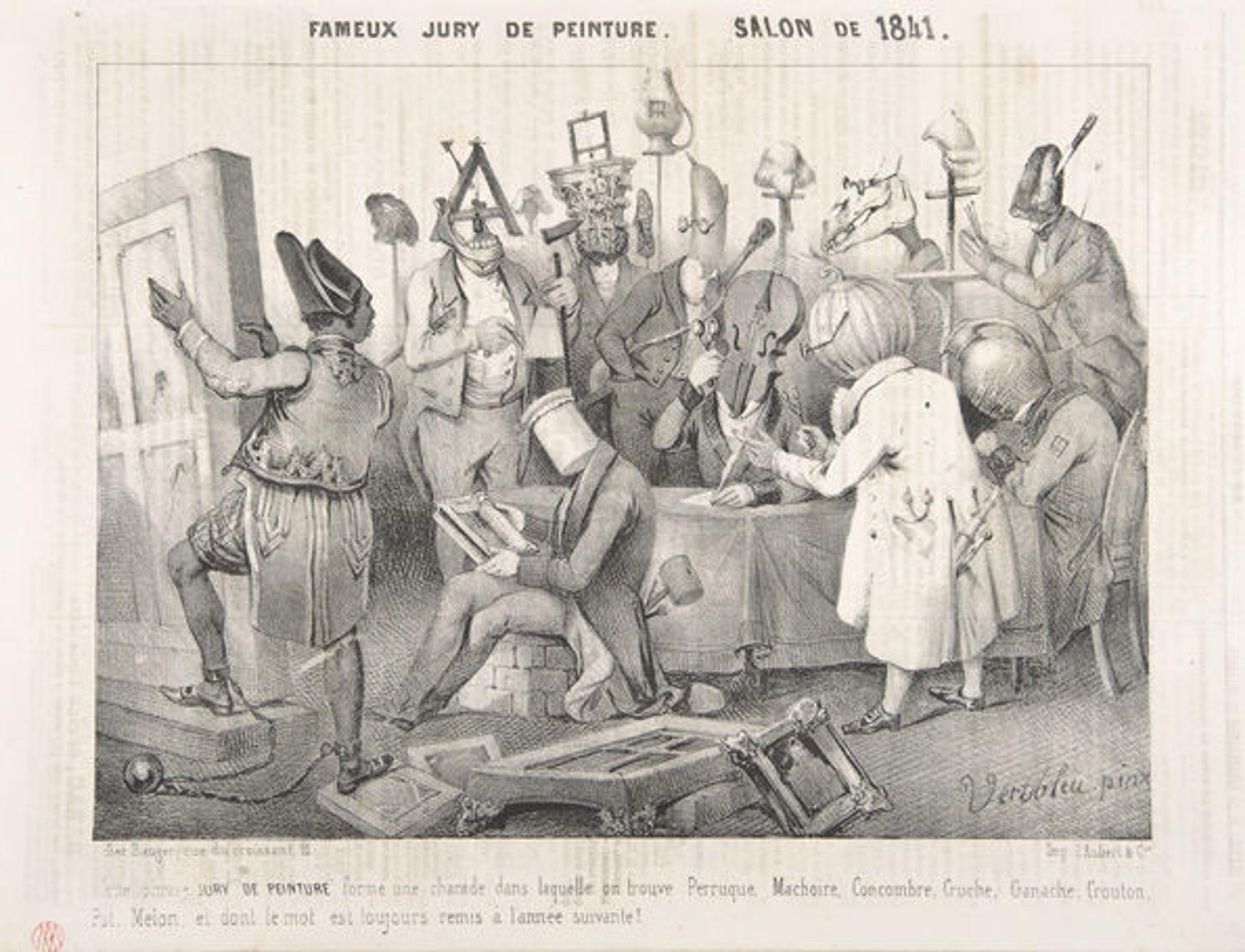

Other prints are tougher to decipher. As we were preparing the exhibition Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine, two works presented particular problems. The first is by Clément Pruche, a contemporary of Daumier, entitled Famous Painting Jury. Salon of 1841.

Clément Pruche (French, active 1831–70). Fameux Jury de Peinture. Salon de 1841., March 20, 1841. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Weston J. Naef, 1985 (1985.1123.156)

The image is clearly a satire on the jury of the annual Salon in France, which was notorious for the number of paintings it rejected. (In 1840, the jury rejected more than half of the 3,996 submissions.) Here the jurors of 1841 are shown with heads as objects, and the French inscription identifies them: Perruque, Machoire, Concombre, Cruche, Ganache, Crouton, Pot, Melon. Based on a precedent set by Delacroix, it occurred to me that the words might be puns on the names of the jurors. I e-mailed scholars around the world to track down the identities of jurors of the 1841 Salon, but the few names that came back didn't relate to the words in the inscription. I am fluent in French, and because I knew the meanings of the words it didn't immediately occur to me to look them up in a dictionary—until I considered ganache. I know ganache as the yummy chocolate stuff in the center of a molten chocolate cake, which doesn't correspond to anything in this image. When I looked up the word in a dictionary, I came across an alternate definition: "jawbone of a horse," which is clearly included in the image. Reading further, I found: "(colloq.) Booby, blockhead." Indeed, the words that I had been trying to connect to names of specific salon jurors were simply nineteenth-century colloquial terms for people who were either too old for their positions [perruque (wig)], stupid [machoire, concombre, cruche, ganache, melon (jawbone, cucumber, jug, jawbone of a horse, melon)] or very bad painters [crouton (bread crust)].

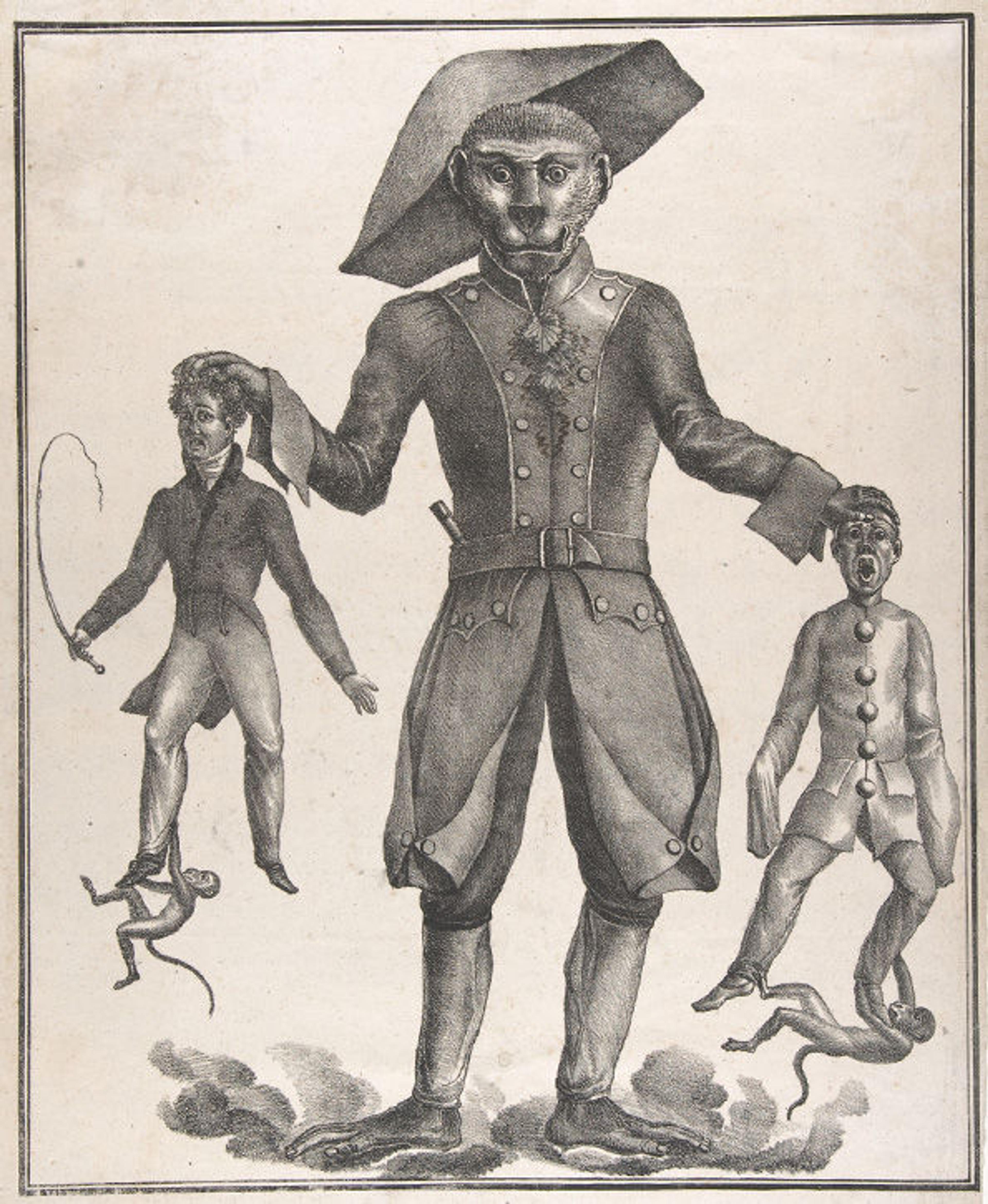

A Giant Monkey in Uniform Holding up Pierrot and a Man with a Whip, after 1825. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1990 (1990.1064.1)

The second puzzling print in this exhibition remains a mystery. This large, early lithograph shows a giant monkey in a uniform holding up two men: the one at right is dressed as a Pierrot; the one at left, holding a whip, looks like a lion tamer or perhaps a carriage driver. Without inscriptions, this work's only chronological hint is the simplified Pierrot costume, which was not developed until around 1825 by the famous stage actor Jean-Gaspard Deburau. So we know that the work dates to that year or after, but we have no other clues. A print that the Museum purchased at the same time, which seems to be by the same artist, is even weirder:

Monsters, Monkeys, and Men, ca. 1820. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1990 (1990.1064.2)

We're calling it Monsters, Monkeys, and Men for lack of a better title, and it shows a hellish landscape. A draped monkey rides a carriage pulled by lions, another monkey with a gun flies overhead in a balloon, and a woman in empire dress flies nearby on an eagle; on the left stands a large creature with a large nose and glasses who holds a club in one hand and an ape-headed soldier in the other.

What could the figures in these two works represent? Do they relate to contemporary politics? Until we have more information, we can only imagine what these images would have meant within their nineteenth-century world.

Related Links

Exhibition: Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine

Curatorial Department: Drawings and Prints