Installation view of Art and Peoples of Kharga Oasis, on display through September 30, 2018 in gallery 302

«If you had the choice to decorate your future tomb with art, what would you take with you to the afterlife? How would your choices reflect your cultural and religious identities? This question is one of the central themes in the exhibition Art and Peoples of Kharga Oasis.»

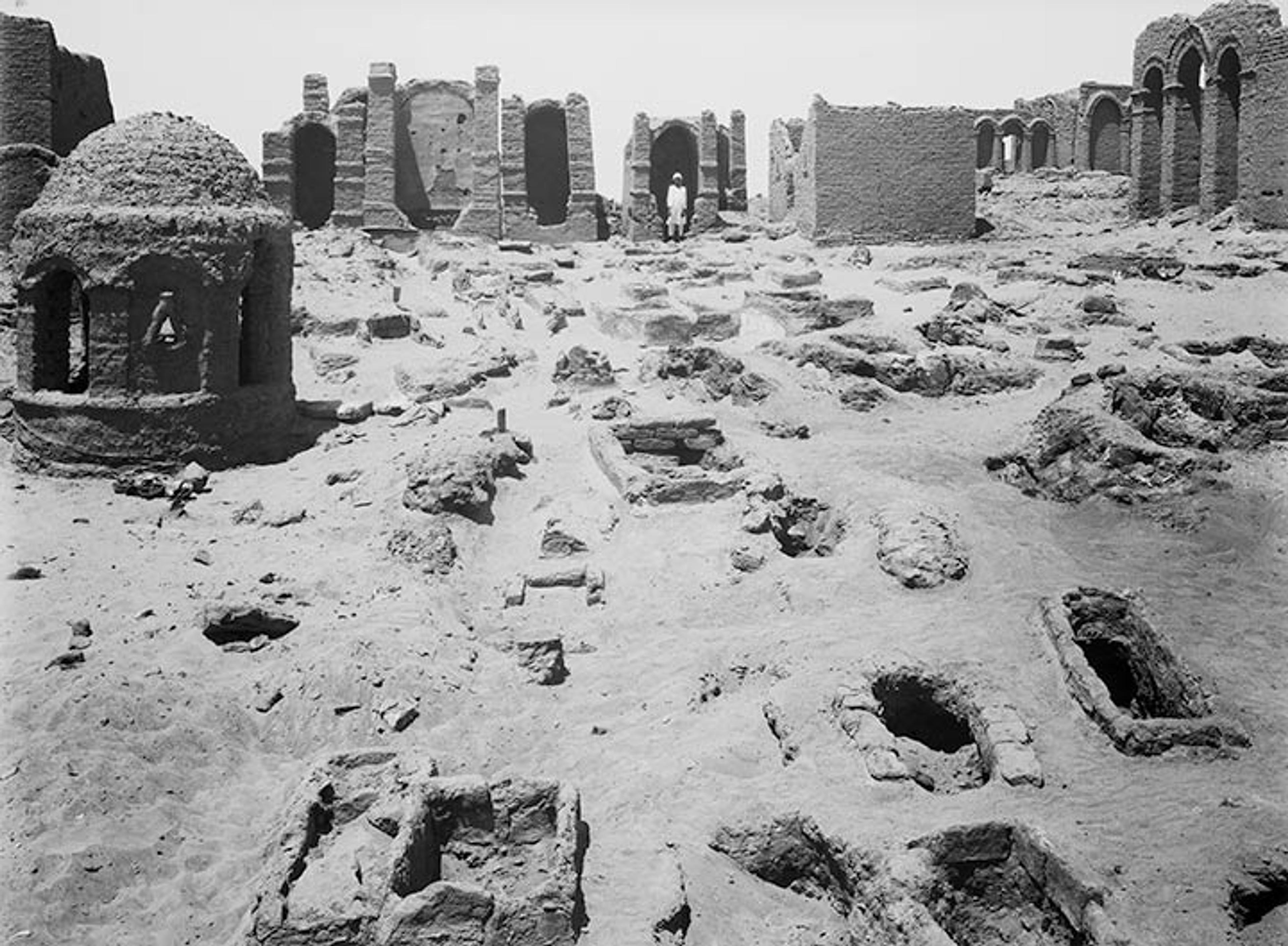

View of Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis, which contained over 200 tombs arranged along streets

Located in the Western Desert of Egypt, Kharga Oasis was first settled in the Paleolithic period (around 50,000 years ago). From the third millennium B.C. through the sixth century A.D., the Oasis played an important economic and military role in Egypt. Kharga was a stop on a trade route that connected sub-Saharan Africa to the Nile Valley, as well as an army outpost that protected Egypt's desert border. Merchants, soldiers, and craftsmen were among the peoples who lived in the area. In late antiquity, the region bore witness to the growth of an expansive and vibrant Christian community; and by the late fifth century, Kharga became a place of political refuge for those exiled from places as far as Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

Egypt, showing the location of Kharga Oasis. From An Oasis City, Roger S. Bagnall et al. © 2015 Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, NYU Press. Distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial 4.0 License

The analysis of Christian and late-antique art and archaeological materials in Egypt can be complicated. In general, excavations throughout Egypt have focused on Pharaonic remains, which often lay buried under later Christian or Islamic structures. In 1907, however, The Metropolitan Museum of Art sent an excavation team to the Western Desert to focus specifically on the early Christian remains, such as churches, monasteries and Christian cemeteries. The Met conducted excavations in this area from 1907 to 1931.

Kharga Oasis was uniquely well preserved due to its inaccessibility from the Nile Valley—from antiquity through the early 20th century, travel from the Nile to the Oasis took four or five days. This state of preservations enabled the archaeologists to successfully identify the art of late-antique Kharga through their projects. Today, the Kharga collection at The Met enables researchers and visitors to learn about art in the late-antique Mediterranean world. Many Western scholars do not have access to the materials in Egypt. For scholars trying to understand the development of early Christian and late antique art in this region, the art in this exhibition represents an essential piece of the puzzle.

Seventy-nine pit graves in Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis, 1907–8. Photography by the Egyptian Expedition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

One of the sites excavated by The Met's team was the expansive necropolis (or, "city of the dead") of Bagawat. The art found in the necropolis represents the many different ways the peoples of Kharga carried their cultural and religious identities into the afterlife. Although the people of Kharga lived on the outskirts of the ancient Greco-Roman world, they selected and used visual cues in their art that connected them with the Mediterranean. Some of the most important early discoveries of the excavation were the wall paintings, which juxtapose Greco-Roman, early Christian, and ancient Egyptian motifs and themes.

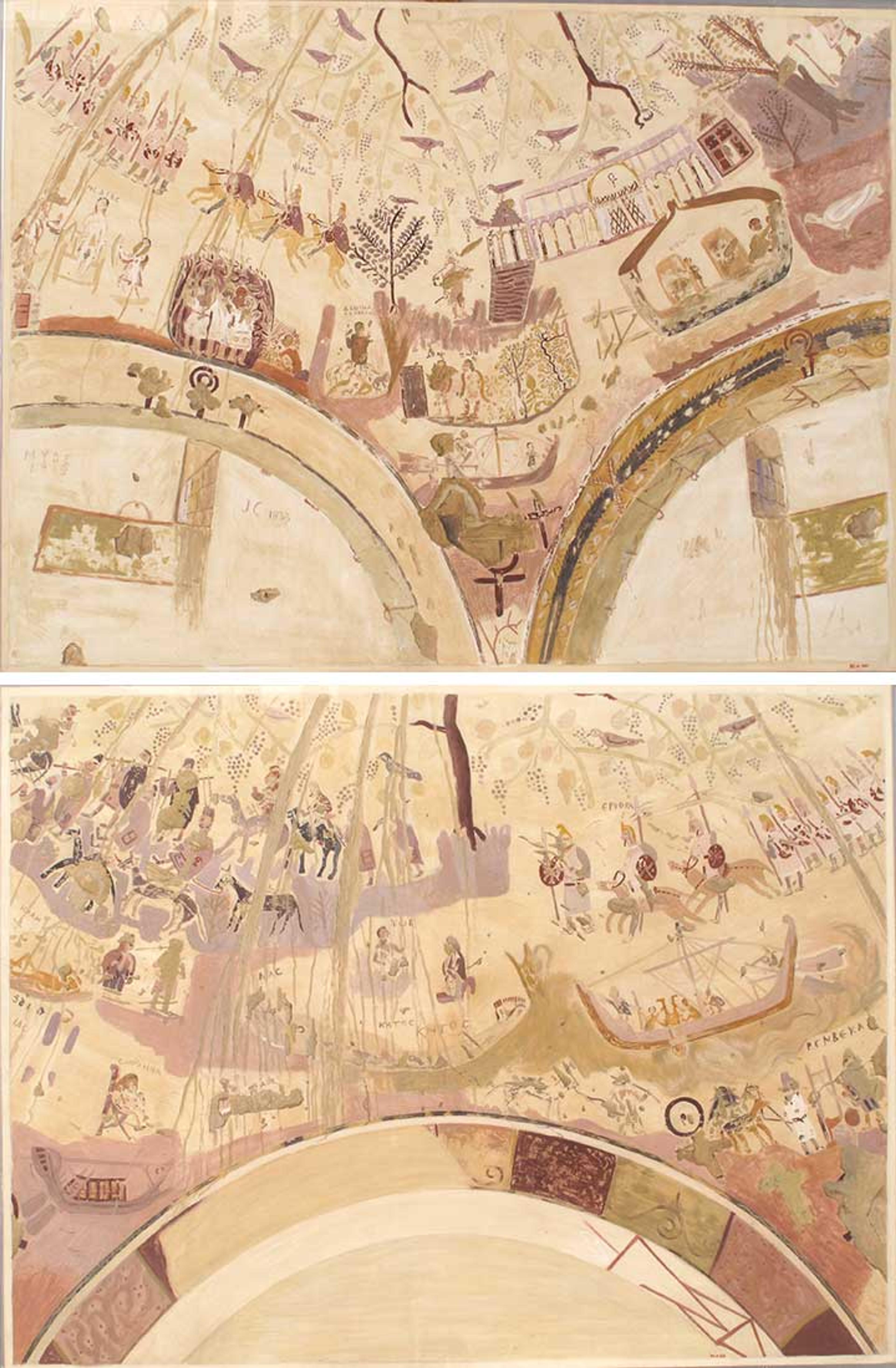

Because the archaeologists used black-and-white photography to document their excavations, they painted exact copies in tempera on paper to record the richly colored wall paintings.

Left: Charles K. Wilkinson. Facsimile of the apse painting in tomb 25 (detail). Egyptian, 2nd century or later. Tempera on paper, 26 3/4 x 18 7/8 in. (67.9 x 47.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1930 (30.4.227)

The examples in this exhibition are reproductions of the original paintings, but in a smaller scale. Since few of the original paintings survive on the site, the reproductions form an important part of The Met collection. Not only do they document art that is not easily accessible to the general public because they are in Egypt's Western Desert, where the U.S. Department of State has issued travel warnings, but they are also some of the earliest surviving examples of paintings made by Christians.

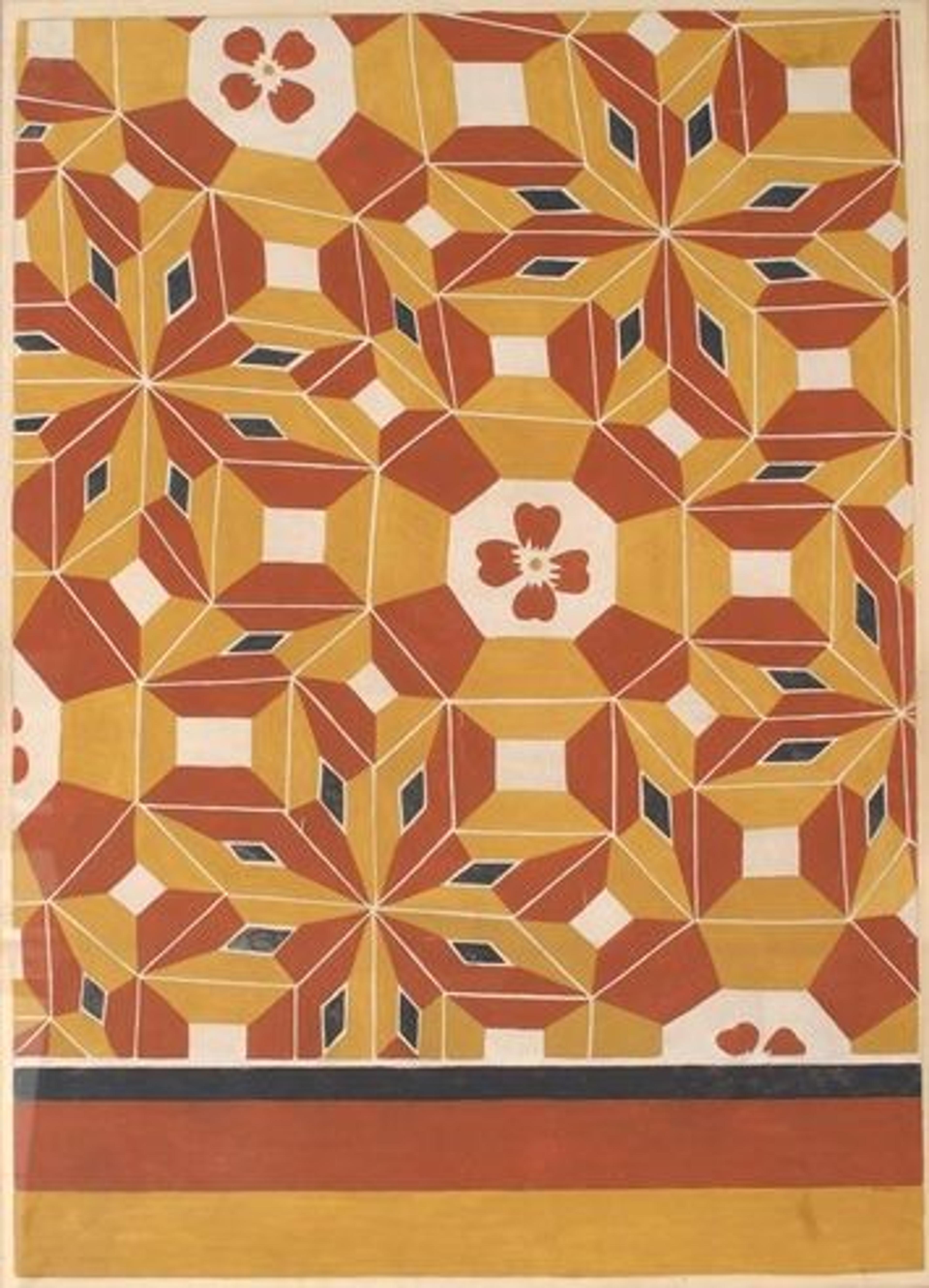

We can find many connections between wall paintings uncovered at Bagawat and artworks displayed at The Met from other regions, in particular Italy and modern-day Turkey. In a reproduction of the apse painting in Tomb 25 at Bagawat (above), the geometric composition resembles patterns found in both funerary and domestic contexts throughout the Mediterranean. We see a comparable geometric pattern and set of colors in a second-century Roman floor mosaic at The Met.

Mosaic floor panel, 2nd century A.D. Roman. Stone, tile, and glass, 89 x 99 in. (226.1 x 251.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest 1938 (38.11.12)

This mosaic was uncovered in a villa at Daphne, a holiday resort near Antioch (modern-day Antakya, Turkey). While there are distinct differences between the two examples in medium, function, and the geometric shapes, the striking similarities between the wall painting from Tomb 25 and the floor mosaic from Daphne highlight the way in which the people of Kharga participated in the visual culture of the Mediterranean world.

Another example of the links between painting from Kharga and art from the Italian and eastern Mediterranean can be seen in the Chapel of Exodus.

Charles K. Wilkinson. Facsimiles of the dome painting of the Chapel of Exodus, Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis. Byzantine Egypt, 4th century A.D. Top: Tempera on paper, 20 1/2 x 27 3/4 in. (52.1 x 70.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1930 (30.4.141). Bottom: Tempera on paper, 19 7/8 x 26 1/4 in. (50.5 x 66.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1930 (30.4.226)

The ceiling of the chapel is decorated with examples of early Christian painting that feature both ancient religious and Old Testament iconography. These ceiling paintings mirror art found in Roman catacombs. Divided into three registers, the scenes read right to left. One section of the dome (top) depicts Noah's ark, Jonah and the whale, Adam and Eve, Daniel in the lion's den, and one of the earliest Christian representations of the prophet Isaiah. On another part of the dome (below), the Egyptian pharaoh and his army follow Moses and the Israelites on their journey through Sinai. Other biblical figures include Rebecca, Job, and Abraham.

These scenes were often found in early Christian funerary contexts and represent a standard visual vocabulary in the Mediterranean.

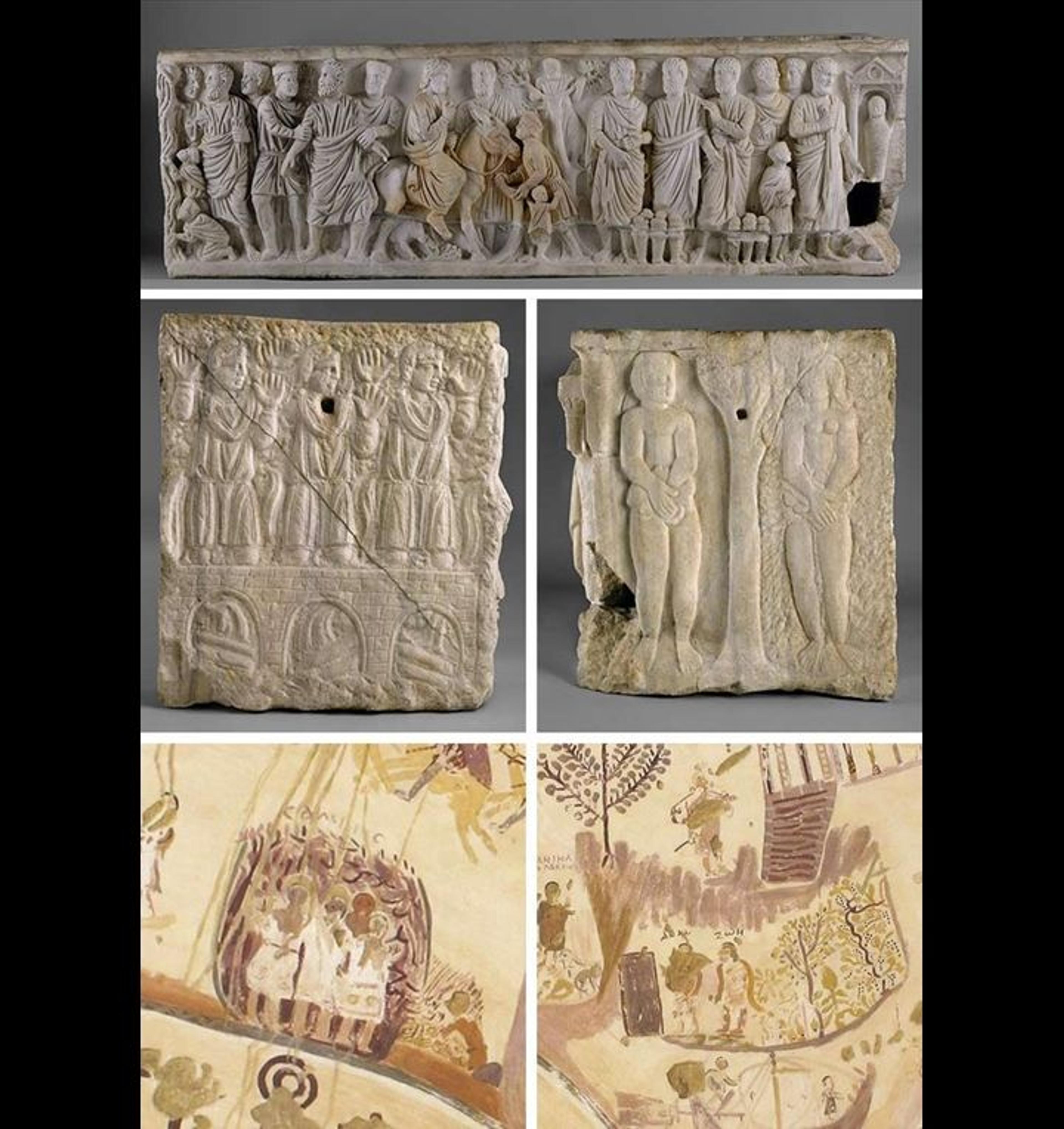

First and second rows: Sarcophagus with scenes from the lives of Saint Peter and Christ, early 300s, with modern restoration. Rome, Villa Felice (formerly Carpegna). Marble, 26 1/2 x 83 1/2 x 24 3/8 in. (67.3 x 212.1 x 61.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Josef and Marsy Mittlemann, 1991 (1991.366). Third row: Charles Wilkinson. Facsimile of the dome painting of the Chapel of Exodus (two details) (30.4.141). Left: Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace; right: Adam and Eve after the Fall by the Tree of Knowledge

For example, a sarcophagus in the Museum's collection that was uncovered at the Villa Felice (formerly Carpegna) in Rome is best known for its scenes from the lives of Saint Peter and Christ (top row). But the sarcophagus also includes scenes depicting Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace and Adam and Eve after the Fall by the Tree of Knowledge (second row), imagery that also appears on the ceiling of the Chapel of Exodus at Kharga (third row). To early Christians, these scenes were prophecies of Christ's salvation.

Both the ceiling painting at Kharga and the sarcophagus at Rome point to the common themes that early Christians wanted to accompany them into the afterlife. The paintings in the Bagawat tombs were decorated with motifs and imagery that connects Kharga to Christian communities throughout the Mediterranean. But the people of Kharga also incorporated traditional Egyptian motifs that articulated their cross-cultural heritage, revealing the intersectional identities of the people who were buried in the tombs.

Portrait of man on half-painted panel, 2nd–4th century A.D. Roman or late Roman. From Tomb LXVI, Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis, Byzantine Egypt, Coptic. Wood, paint, 16 1/2 x 11 x 2 in. (41.9 x 27.9 x 5.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1931 (31.8.2)

This can be seen in a coffin panel from Tomb 66 (above). Found in a tomb with Christian imagery, this portrait of a man on a half-painted panel has motifs in common with ancient Egyptian art—a hawk and a sistrum. The panel was sawed in half before it was placed in the burial chamber, and only the right side was recovered. Some scholars therefore believe that the panel may have been a reused object taken from an Egyptian coffin, similar to the Fayyum Mummy portraits (below).

Right: Portrait of a thin-faced man, 2nd century A.D. Egypt, Roman. Encaustic, limewood, gold leaf, H. 16 5/8 x W. 7 3/8 in. (42.3 x 18.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1909 (09.181.3)

Repurposing traditional Egyptian objects in Christian contexts was a popular practice in the late-antique to Byzantine period in Egypt.

However, it is also possible that the Bagawat panel was not originally created for a funerary context. For example, the construction of the panel resembles that of votive panel paintings from Roman Egypt. The implications of these two painting types—mummy portraits (left) versus votive panels—are significant. If the Bagawat panel is a mummy portrait, then the man depicted might represent a deceased person. On the other hand, if the panel is a part of the votive panel lineage, then it likely represents a god or cult figure. A technical analysis of the panel would enable researchers to understand whether and how this artwork fits into the newly studied corpus of panel painting.[1]

The artwork in the exhibition Art and Peoples of the Kharga Oasis displays many connections with other objects on view at The Met, revealing the links that the people of Kharga had to the greater Mediterranean world. After viewing the exhibition, I hope you will ask yourself, what works of art reflect your identity? What would you want to bring to your grave?

Note

[1] For the corpus of panel painting, see Thomas F. Matthews with Norman E. Muller, The Dawn of Christian Art in Panel Paintings and Icons (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2016).

Related Content

"Excavations in Kharga Oasis," a digital walkthrough of the exhibition

Art and Peoples of the Kharga Oasis, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through September 30, 2018