Critiques of Power and Toxic Masculinity—Kelly Baum on Leon Golub: Raw Nerve

Installation view of Leon Golub: Raw Nerve, on view at The Met Breuer through May 27, 2018

«Those who knew Leon Golub will tell you that he was one of the most caring artists you could meet, a personality seemingly at odds with his paintings—merciless, unflinching expressions of what he called "the nightmare of history"—a nightmare that "has no beginning and no end."[1] Leon Golub: Raw Nerve, on view at The Met Breuer through May 27, 2018, is the first museum retrospective of the painter in this country since a 2001 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. It wastes no time catching us up to the artist's work. On the morning that I interviewed Kelly Baum, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky Curator of Contemporary Art, who organized this survey, I arrived at the galleries shortly before she did. While I waited, I took a seat near Golub's final paintings, a vantage from which I could see, as the elevator doors opened, shock wrench the groggy faces of early-morning visitors.»

Will Fenstermaker: I've been watching people come off the elevator and walk into this exhibition, where they're immediately faced with Gigantomachy II, a brutal, titanic painting: They jolt.

I imagine that this kind of painting could seem like the capstone to a career, with its size and power, its monumentality. Something to work toward. But in Leon Golub's career, it's almost a kind of beginning. In some ways, things only get more intense from here.

Kelly Baum: Yes, Gigantomachy II, from 1966, is one of five paintings from Golub's series Gigantomachy, which were inspired by the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon. Golub was very interested in relief sculptures and friezes, and he sought to translate this effect to paintings whose figures seem to leap off of the canvas.

He began the Gigantomachy after he returned from Paris, where lived between 1959 and 1964 with his family: the artist Nancy Spero and their sons. While he was in Europe, he devoted quite a bit of time to studying the art of the past, and the work that he made when he returned from Europe reflects his investigation of art-historical motifs.

Most art historians and curators associate the late 1960s with minimalism, conceptual art, and Pop. But Golub fit into none of those categories. He forged his own path forward and was critically neglected for it. It wasn't until the early 1980s that he experienced a renaissance of sorts and achieved the recognition he deserved.

Will Fenstermaker: Was that because of the visceral and political nature of the work?

Kelly Baum: In the 1980s, the art world saw an explosion of excitement around figurative painting and politicized art. Thanks to the synchronicity between his work and the work of a younger generation of artists, Golub's art finally became legible to a public.

Will Fenstermaker: What are the other themes Golub started to develop in the Gigantomachies?

Kelly Baum: Around this time, he also started creating an archive of images, which began with photographs of Greek sculptures and modern athletes—wrestlers, soccer players. . . . So the Gigantomachy series reflects both his study of antiquity and his study of photographs, from which he pulls facial and physical gestures.

Gaia pleads with Athena to spare her sons. Gigtantomachy frieze of the Great Altar to Zeus and Athena at Pergamon (detail). Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

In the Gigantomachy series, Golub fused his interest in figurative painting, the art of the past—in particular, ancient Greek and Roman art—and his commitment to politics. Golub also spoke about the violence in these paintings as being existential as much as physical. These scenes of violence represent man's internal struggle, his struggle with himself, as much as they do his struggle with other human beings. The Gigantomachies were produced during the Vietnam War, but at this point Golub wasn't quite ready to address the war outright, and so he allegorized violence, brutality, and injustice through these ahistorical paintings of men fighting with one another.

Will Fenstermaker: This idea of humanity arising through conflict is both existential and Greco-Roman. It's hard not to think about Golub in relation to Anselm Kiefer upstairs, who is also very interested in ruins and fractured forms, and, to a lesser degree, their relationship to violence.

Kelly Baum: Absolutely. Golub said again and again that he preferred the ruin and the fragment to the perfect and the complete. He wants his figures to appear aged, eroded, and ruined in the same way that ancient sculptures appear to modern eyes.

Will Fenstermaker: In New York, Golub came to The Met frequently. Given his interest in antiquity and art history, it's a natural fit to see him here.

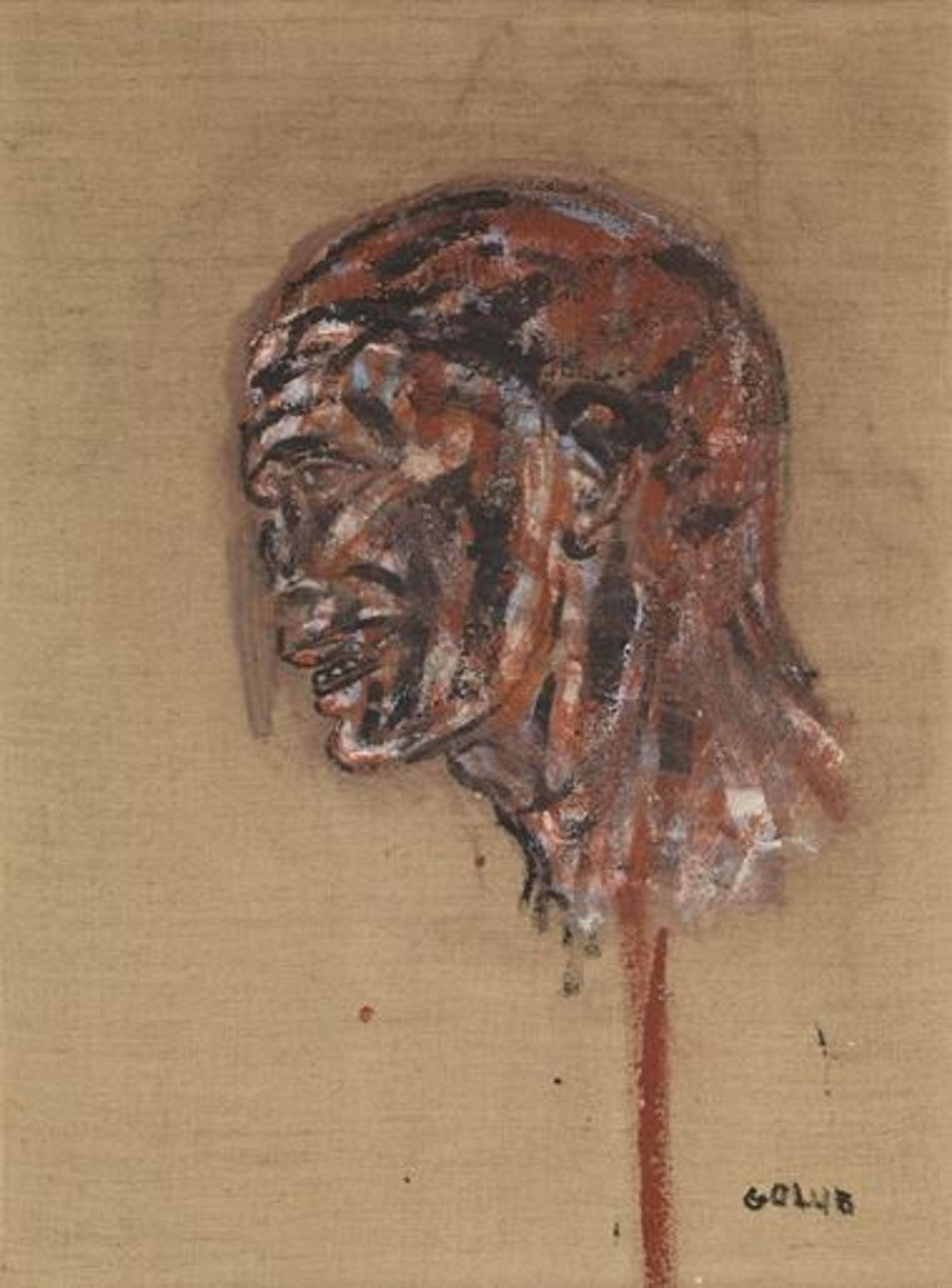

Right: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Vietnamese Head, 1970. Acrylic on linen, 24 x 18 in. (61 x 45.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dan Miller, in loving memory of the artist, 2016 (2016.529.1). Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Kelly Baum: Yes, Raw Nerve was designed to acknowledge two gifts to the Museum: Gigantomachy II and Vietnamese Head. Local collector and designer Dan Miller donated Vietnamese Head, and Golub and Spero's sons offered us Gigantomachy II. That same year, the artist and writer Jon Bird approached Sheena Wagstaff [Leonard A. Lauder Chairman of the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art] with the idea of promising his collection of art by Golub and Spero to The Met. Every work from Jon Bird's collection in this exhibition is an intended gift.

We borrowed additional works from Golub's estate, from his former dealer Ronald Feldman, and from Harriet Horwitz Meyer, who, with her late husband, created one of the best, most distinguished collections of Golub's works in the country.

Will Fenstermaker: Do we know what Golub was looking at when he visited?

Kelly Baum: Definitely. There's a great interview with Golub and Spero by Michael Kimmelman in the New York Times from 1996, based on a tour they took of The Met. They stop at some of their favorite objects. Almost every single one of Golub's works references some art-historical tradition, if not a specific work of art.

But Golub was also a critic of the Museum. On May 22, 1970, he protested on the steps of The Met as part of Art Strike. He also wrote an essay critical of The Met's tendency to hoard art, especially from non-Western countries. He argued that we should repatriate our African collections—which he nonetheless visited and learned from.

Will Fenstermaker: What was Art Strike protesting?

Kelly Baum: Racism, sexism, oppression, war. . . . I mean, this was 1970. There was Cambodia, the Vietnam War, Kent State. . . . So artists called for a general strike in the art world across New York. They called on museums to close their doors to protest the general state of corruption in U.S. politics. The Met refused to close. They made entrance free and they extended their hours, but they refused to close.

New York Art Strike protesting on the steps of The Met on May 22, 1970. Photo © Jan van Raay, courtesy the artist

Will Fenstermaker: That period of time, the sixties and seventies, outside of the art world is generally considered an overtly political era, both in Paris and in New York. Within the arts, it was often quite apolitical.

Kelly Baum: Well, that just depends where you look and who you look at. Abstract form can be as political as content; it just requires looking a little harder and a little differently.

Will Fenstermaker: That distinction reminds me of the one between Clement Greenberg's conception of "abstract expressionism" and Harold Rosenberg's use of the term "action painting." I mean, Rosenberg, who was more politically conscious, used the phrase "an area in which to act," which also calls to mind brutality and violence. An arena is a place in which combat is performed. Obviously, Golub wasn't an abstract expressionist, but is there any connection there?

Kelly Baum: Definitely. For Golub, process and technique were both opportunities to express meaning, to explore violence. For most of his career, he brutalized his surfaces, did violence to his canvases. It's especially apparent in Gigantomachy II where he added and subtracted, applied and removed paint continuously, using implements like meat cleavers. Because of this subtractive technique, the figures appear flayed. He was working on the floor sometimes, too. It took a lot of strength and endurance. I want to emphasize that his very technique, and the effects it achieved, are also political. In at least one piece of writing, he compares his treatment of the canvas's surface to the damage done to skin by napalm, which literally just dissolves the skin off the bones.

Will Fenstermaker: Right, Golub described the Gigantomachy series as a form of "barbaric realism." But in an interview with David Levi Strauss,[2] he also says that the violence he depicts in the picture isn't the same violence as in the Vietnam War. He wasn't able to resolve this contradiction for a while, and it represented a real crisis for him. He almost couldn't paint anymore. How did he go on?

Kelly Baum: Well, eventually he began taking the war as his overt subject. In the late 1960s and very early 1970s, he began a series of Napalm paintings, then his Vietnam series, both of which incorporated direct references to the war in Vietnam. At the very same time, however, Golub was experimenting with abstraction, too. I've included one of his abstractions in the show.

Left: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Pylon V (Napalm Gate Fragment). Acrylic on linen, 108 x 28 in. (274.5 x 71 cm). The Estate of Leon Golub, courtesy of Hauser and Wirth. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Will Fenstermaker: Was he making those abstract paintings at the same time as the Napalm and Vietnam paintings?

Kelly Baum: Yes, their titles—this one is Pylon V (Napalm Gate Fragment)—indicate a very direct connection to the Napalm paintings. In fact, pieces of canvas were cut from his Napalm paintings to make the Pylons.

The exhibition is mostly chronological, but there are times when I break the chronology for a strategic purpose. For example, the first gallery includes works from 1957 through 1994. Here, I wanted to make the point that Golub's primary subject was man—by which I mean masculinity. It's fascinating that he very rarely painted women.

Will Fenstermaker: And when he did, they're often the subject of a power dynamic imposed by a man.

Kelly Baum: I think we take for granted the fact that Golub painted almost exclusively men. He painted men who were at war with themselves and with other men. He painted bad men doing bad things. He painted men who abused power. Really, that was his main subject throughout his career. This entire show is a testament to his critique of toxic, belligerent masculinity.

Will Fenstermaker: There's a series of four portraits of Ernesto Geisel in the second gallery that brings this critique to bear on a real person. The portraits are just faces, but in profile they remind me of classical busts or coins depicting rulers like Julius Caesar, the dictator perpetuo. Those ancient images were early vessels of power; the coins spread Caesar's likeness across the empire, implicitly equating him to a god. But what Golub is doing here is interesting because through four different points in time you get a sense of, well, I don't know what you'd call it—decay?

Kelly Baum: Yes, I think he wants us to sense the physical and internal moral decay of this individual over time. These four portraits are from a group of five—the fifth one stayed with Jon Bird—of the Brazilian general and president Ernesto Geisel. They're all based on photographs of Geisel that Golub clipped from magazines. He recognized their power. In the same way that coins of early Roman leaders were mass-produced and disseminated across the land, so too are photographs of our own leaders today. The photographs of Geisel that Golub used were themselves used to promote and reinforce Geisel's power in Brazil.

Installation view of four paintings by Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Clockwise from top: General Ernesto Geisel, 1976. Acrylic on linen, 15 1/4 x 13 5/8 in. (38.7 x 34.6 cm). General Ernesto Geisel, 1976. Acrylic on linen, 19 3/4 x 19 in. (50.2 x 48.3 cm). General Ernesto Geisel, 1976. Acrylic on linen, 17 3/4 x 12 5/8 in. (45.1 x 32.1 cm). General Ernesto Geisel, 1961. Acrylic on linen, 17 3/4 x 16 3/8 in. (45.1 x 41.6 cm). Intended gifts of Jon Bird

These portraits are part of a series sometimes referred to as the Political Portraits. Golub started them around 1976, during a moment of artistic crisis. When the Vietnam War ended, he found himself more or less without a subject to paint. Then, he noticed that one of the soldiers in one of his Vietnam paintings resembled Gerald Ford and thought, "Maybe I'll paint a portrait of Ford." Thus began the series.

He made more than one hundred portraits of men—supposedly, there are portraits of women but I've not seen them; he may have destroyed them—all of them leaders of some kind. Popes, mayors, secretaries of state, presidents, generals, men who enjoyed incredible power and who also abused the power bestowed upon them. The Political Portraits mark a transition in his practice in a lot of ways. It's where his reliance on photographs becomes apparent. It's also where he starts to demonstrate the relationships between images, media, and power.

Will Fenstermaker: Right, and that's something dictators have always understood—that controlling images is a way of controlling people.

Kelly Baum: Yes, but Golub also recognized that these same photographs could undercut and compromise their subjects' power. What the four portraits of Geisel show over time is the waning of his physical presence, the waning of his authority, the gradual decay and desiccation of his body. They demonstrate not the power and authority of the subject, but his impotence and fallibility.

Golub once compared his Political Portraits to masks. By this, he means two things. First, that his are images of men performing their masculinity and their authority. They're acting out a power and authority that they don't actually own, that they pretend to have, or that they have on loan. He's also saying that the faces he paints are empty, impotent vessels. All surface, no depth.

Will Fenstermaker: They really do have a mask-like appearance to them. They're not entirely realistic. They're gray, they're loose.

Kelly Baum: They're really creepy. The fifth painting, which Jon Bird just couldn't bear to let go, is a profile view that's cropped right at the nose. You get the sense that Golub isn't treating these figures with a lot of respect.

Left: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Abraham Lincoln, 1957. Oil and lacquer on canvas, 81 1/2 x 47 1/2 in. (207 x 120.7 cm). Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection. Right: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Philosopher I, 1957. Oil and lacquer on canvas, 80 x 46 in. (203.2 x 116.8 cm). Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection

Will Fenstermaker: Is that why you've placed them next to The Brank, which depicts a woman in a mask?

Kelly Baum: No. There, Golub is depicting an instrument of torture invented by men in order to abuse women. It makes clear what happens when these men put their minds to abusing others.

Will Fenstermaker: I see. So it's almost as if the Political Portraits are the manifestation of toxic masculine power, whereas The Brank is an embodiment of how that power expresses itself on women. Was Golub a feminist?

Kelly Baum: You know, I've read almost everything Golub ever wrote, as well as nearly every interview with him, and I'm not sure he ever described himself as a feminist. He was somebody who really knew how dangerous a certain kind of masculinity could be—for women, for the world—so there is a feminist politic to Golub's work. He was married to one of the greatest feminist artists of her day, Nancy Spero.

Will Fenstermaker: Who almost never painted a man.

Kelly Baum: Yes, which is really interesting.

Will Fenstermaker: So did his feminism manifest mostly as a critique of certain masculinity? As opposed to Spero, whose work could be read as an embodiment of what you might call "feminine power."

Kelly Baum: Well, she was also making works like the Torture of Women series that were critical of violence against women. That's where their politics were very similar. But yes, Golub's feminism—if he was a feminist—manifests as a critique of masculinity, whereas Spero's feminism manifests as a critique of violence against women, and as an endorsement of female pleasure, power, and desire.

Will Fenstermaker: Golub and Spero collaborated on a print related to Spero's Codex Artaud series, which is in the exhibition. Antonin Artaud was also obsessed with brutal expressionism. Listening to recordings of him reading his work is unsettling even if you don't understand French. In the wall texts, you mention Jean Dubuffet too. Was an interest in art brut something that Golub and Spero picked up in Paris?

Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Gigantomachy II (detail), 1966. Acrylic on linen, 9 ft. 11 1/2 in. x 24 ft. 10 1/2 in. (303.5 x 758.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts and Stephen, Philip, and Paul Golub, 2016 (2016.696). Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Kelly Baum: They would've picked it up in Chicago, actually, where Golub was born and bred. Dubuffet visited Chicago in the 1950s for a major exhibition of his work. He also delivered a lecture at that time, and we know that Golub attended. Golub was also part of the Monster Roster group of Chicago-based artists who were already developing an interest in representing the figure in an absurdist, expressionistic vein. The Monster Roster artists were familiar with art brut—what we call Outsider Art—and the art of insane. Dubuffet landed in Chicago at just the right moment in order to reinforce these pre-existing interests.

Artaud, on the other hand, was someone who Spero picked up when she lived in Paris with Golub. Her Codex Artaud series documents her encounter with his writing, especially with the notebooks he penned while he was in a psychiatric asylum during the Second World War. She began to identify with Artaud and with his experience of rage and alienation, his revolt against law and language. She had a lot of sympathy for him, but I don't know the extent to which Golub shared that.

Will Fenstermaker: Quoted in one of the object labels, Golub uses the phrase "the theater of reality." Is that not a reference to Artaud's book The Theater of Cruelty?

Kelly Baum: It's hard for me to imagine that he and Spero weren't reading The Theater of Cruelty and the playwrights of the Theater of the Absurd, like Samuel Beckett, who were all very much in vogue. But this quote is very complicated. Golub says, "This is not a theater of the absurd, but a theater of reality." Theater and reality are not the same thing. It's interesting that his reliance on the word "theater" suggests that there's an artificial, performative quality to reality.

Will Fenstermaker: And that this performative quality isn't absurd.

Kelly Baum: Exactly. Although, I think of absurdist plays from the fifties and sixties as being very current, very topical, even if they're allegorical. So maybe Golub is expressing his frustration with works of art that are elliptical and circuitous. He wants something for art that is more direct and concrete, something that's rooted in the present in a more direct way.

Right: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Horsing Around IV, 1983. Oil on canvas, 120 x 85 in. (304.8 x 215.9 cm). Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection

Will Fenstermaker: And at this point, he's certainly dealing with power more directly than in, for example, Gigantomachy II. In this gallery, women appear. We've just touched on how the few women who appear in Golub's paintings are often subject to a power dynamic imposed by a man.

Kelly Baum: Yes, but they're not absolutely and emphatically on the losing end of that power dynamic, which is one of the reasons why I'm so intrigued by paintings from the Horsing Around series, for instance. Works from this series represent the same mercenaries and interrogators you see in Golub's White Squad and Interrogation paintings. But instead of abusing other men, they're taking advantage of female prostitutes. In the painting in this exhibition, for instance, a white man pulls the shirt down off the chest of a black woman, exposing her breast.

Will Fenstermaker: Yeah, he's a leering creep. You can see his gums around his teeth.

Kelly Baum: It's really visceral and disturbing. There's something about the watch poking out from the sleeve. . . . We don't see his feet; the canvas is cropped in such a way that suggests he's in our space with us. Golub creates the illusion that we're standing in the bordello with him. But are we another prostitute or another mercenary?

Will Fenstermaker: We're complicit in some way, but he leaves it to us to figure out how.

Kelly Baum: Definitely. We're complicit spatially but also ethically. He wants us to position ourselves morally in relation to these figures. Golub's painting is overtly critical of abusive masculinity, and he wants us to take a stand.

The prostitute he presents is a very complicated figure in this narrative. She's the victim of the mercenary's advances, but in her posture, her expression, she's not consumed by or reduced to her own victimhood. There's something about the way that she presents herself physically that suggests she's no helpless target. She holds something back, guarding some of her autonomy.

Will Fenstermaker: She's not powerless herself.

Kelly Baum: Exactly. These paintings from the eighties and nineties are so nuanced. Compare this to Vietnamese Head around the corner, which is a painting of a victim of the Vietnam War, a severed head mounted on a pike. Vietnamese Head depicts an abject victim, but in Horsing Around there's no such abject victim.

In paintings like these, Golub has more than just sympathy for those female victims of male lechery; I think he has respect for them, for their ability to survive and persist. You can appreciate these paintings for the way he's critiquing social, racial, and sexual injustice, but you can also appreciate them for the sensitivity with which he's painting subjects, particularly black subjects.

Golub's palette also changes a great deal—expands and brightens—in the 1980s. He moves from a palette of grays and blacks, with touches of pink and blue, to a chromatic explosion. These purple tights? The yellow shoes? I mean, my god!

Will Fenstermaker: Where do you think that embrace of color came from?

Kelly Baum: I wish I knew more about why his palette changed so radically. It's a topic for further research.

Left: Golub's Horsing Around IV, 1983. Right: White Squad VIII, 1985. Oil on linen, unstretched with grommets at top edge, 120 x 144 in. (304.8 x 365.8 cm). Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts

Will Fenstermaker: The painting in this gallery from White Squad is from 1985, two years later than Horsing Around IV. It loses a lot of that color.

Kelly Baum: Yeah, this uses the same palette as Pylon, Vietnamese Head, and Gigantomachy II. You don't see that powder blue he has a preference for, but he starts to use red oxide for the backgrounds. He's thinking especially about ancient frescoes from Pompeii.

In all of Golub's works, you'll notice that there is no deep space. The forms, the motifs, the figures, and the subjects are always pressed right up against the picture plane. He also increasingly creates the illusion that his figures are about to crawl out of the canvas and into the viewers' space. That's part of his way of establishing contact with the spectator. He does that in order to activate our ethical and political nerves. He wants to turn us on like a light switch.

I think Golub structures his paintings this way to implore us to intervene, forcing us to make a choice by positioning us phantasmatically in relation to the canvas. So are we a bystander? Will we help or will we run away? In the case of the White Squad painting in the exhibition, are we another mercenary about to hit this guy over the head with a club? Or are we another victim lying on the floor? Whichever it is, you can't remain passive or noncommittal. Golub won't allow it.

Again, a lot of these paintings are based on photographs of soldiers, which he clipped from magazines like Solider of Fortune. The most famous painting from the White Squad series is an image of a man stuffing a body into the trunk of a car. In the photograph, the man is looking down or back into space, but in the painting, he turns and engages our eye.

Left: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Mr. Amok, 1994. Ink and gouache on paper, 8 x 6 in. (20.3 x 15.2 cm). Intended gift of Jon Bird. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Will Fenstermaker: Golub had an ongoing interest in the image environment—he collected news media photographs, pornographic stills, and other images. Did he collect them for specific artistic reasons, or was it a way of studying our relationship to images in general?

Kelly Baum: Golub had long been an image scavenger and he relied quite a bit on his vast image archive to make paintings, but I think his relationship to photography changed over time. Initially, Golub understood the archive as a resource from which he would draw inspiration—gestures, uniforms, weapons. Then he began to understand the archive as a document of the world's relationship to images in general.

Just as the sixties and early seventies are associated with minimalism, the late seventies and early eighties is associated with the Pictures Generation, artists like Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler who make works of art about images and the subject of representation as a whole . . .

Will Fenstermaker: The phenomenon of images.

Kelly Baum: . . . and who emphasized the mediation of identity by images. Golub was thinking about that as well, which is one of the reasons why his works resonated so powerfully in the 1980s. He shared younger artists' interest in the role of images in contemporary life. His interest even predated theirs.

Will Fenstermaker: You see that a lot with artists who make archives. I always think of Gerhard Richter's Atlas. That project is a way of situating oneself within an image-centric culture, of figuring out one's relationship to a larger society by studying the ways it makes and disseminates images. You used the word "identity."

Kelly Baum: So many of Richter's paintings are based on photographs too, but the results are quite different than Golub's. Richter really insists on and emphasizes the relationship of his photo-based paintings to the photograph. Golub didn't really do that, at least in his early paintings. He was open about his reliance on photographs as source materials, but he doesn't necessarily make that evident in the paintings themselves, which emphasize immediacy rather than mediation. In the paintings from the 1980s and 1990s, however, Golub seems to advertise more overtly the role of images.

Will Fenstermaker: Do you know why?

Kelly Baum: I think he refined and deepened his understanding of the way that images mediate our relationship to the present, to history, and to ourselves.

Will Fenstermaker: The degree to which our experience of the present is an experience of images.

Kelly Baum: I wrote my dissertation on the Situationist International and Guy Debord, who wrote Society of the Spectacle in 1967. Golub came to similar realizations slightly later and he doesn't talk about them in the same way. I think there's work yet to be done in unpacking his relationship to images, but you get the sense that he's both fascinated and repelled by our dependence on images and their proliferation.

Golub understood the power of images, but there was also something about that power that excited him. He was diagnosing our addiction to images, and that became part of the narrative of his paintings. They demonstrate or perform a theory of representation.

Will Fenstermaker: When Golub passed in 2004, that debate was still ongoing—it continues today, even. That same year, Susan Sontag wrote—this phrase always stuck with me—that the belief that reality is spectacle is a "breathtaking provincialism" that ignores real suffering.[3] She was making the point that there's something else besides voyeurism—there's also a culpability. Just looking at an image implicates a viewer to what's going on inside that image.

The way you describe Golub, it seems to me he was making that same argument along a painterly route, as opposed to a photographic one.

Kelly Baum: Absolutely. His views on photographs, images, and representation were very nuanced, but he's not really given credit for it. David Levi Strauss, whom you mentioned, is one of the few to take Golub's interest in images and photography seriously. Instead, Golub's work is often consigned to figurative painting with a dose of expressionism and politics.

Left: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). The Conversation, 1990. Acrylic on linen, unstretched with grommets at top edge, 92 x 170 in. (233.7 x 431.8 cm). Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection. Right: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Two Black Women and a White Man, 1986. Acrylic on linen, 120 x 163 in. (305 x 414 cm). Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

Will Fenstermaker: The portraits in the next gallery are interesting in thinking about the politics of looking. I couldn't help making an association with David Hockey's double portraits. Both Hockey and Golub seem to be triangulating different gazes into a complicated relationship.

Kelly Baum: It's true. The two men in The Conversation are standing in front of a mural that represents a man, probably a worker, with his fist raised; it is a painting within a painting, an image of an image. Golub very carefully triangulates the gazes between the three figures: each looks toward and usually just past the other. Their gazes just miss each other. There's a story to be told in the missed gazes, in the missed opportunities to see and communicate.

Will Fenstermaker: What do you think Golub's doing here?

Kelly Baum: I don't know! [laughs] These late works are very mysterious. Golub was thinking and reading a lot about South Africa at this time and he was a vocal opponent of apartheid, so perhaps this painting is an allegory of racial injustice set in Johannesburg? A colleague who saw the painting, though, suggested Cuba circa 1960 as a setting. So perhaps the work is instead a story about the failed promise—or the future potential—of political utopia.

Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Two Black Women and a White Man, 1986. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts

Golub painted many black subjects in the 1980s and 1990s. Some paintings addresses racial and gender inequity overtly, but others are more mysterious—even when a twisted power dynamic is obviously at play, as in the other painting in this gallery, which features two black women with extraordinary gravitas, dignity, and authority, sitting near a white man, who stands to the side and averts his gaze from them. Unlike the women, the man looks kind of rotten and twisted, not unlike Ernesto Geisel.

There's very, very little written about Golub's paintings of black subjects in the 1980s and 1990s. They also represent a body of work by Golub with which I was unfamiliar. I made a point of including them in this show for just that reason: I wanted to become better acquainted with them, and I wanted others to do so as well. They also resonate with a great deal of contemporary art in which the black subject, more often than not represented by a black artist, assumes pride of place. What can we learn about Golub by considering his work in relationship to theirs? And vice versa?

Will Fenstermaker: Golub's entire career was based on a critique of a form of power that our society in many ways bestows upon white men in particular. So it makes sense that by the time he gets to this point of his career, he's well aware of how the depiction of black subjects by white artists is historically fraught with problematic power dynamics.

Kelly Baum: It's rare for a white American artist in the eighties and nineties to paint black subjects who are as nuanced, sympathetic, and powerful as Golub's. One of his paintings, representing three black men in conversation, was included in Thelma Golden's 1994–95 exhibition Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary Art at the Whitney. Golden recognized something of importance in this body of work, something to be recovered and studied by curators and art historians. Perhaps it's the way Golub was able to strike a balance between recognizing the hardships that his black subjects face by virtue of their race—the specific forms of violence they suffered at the hands of whites—but simultaneously recognizing their fundamental humanity, autonomy, and power. Golub never makes victims of the black men and women he paints, even though he was deeply concerned with the ways they were victimized. That's very interesting to me.

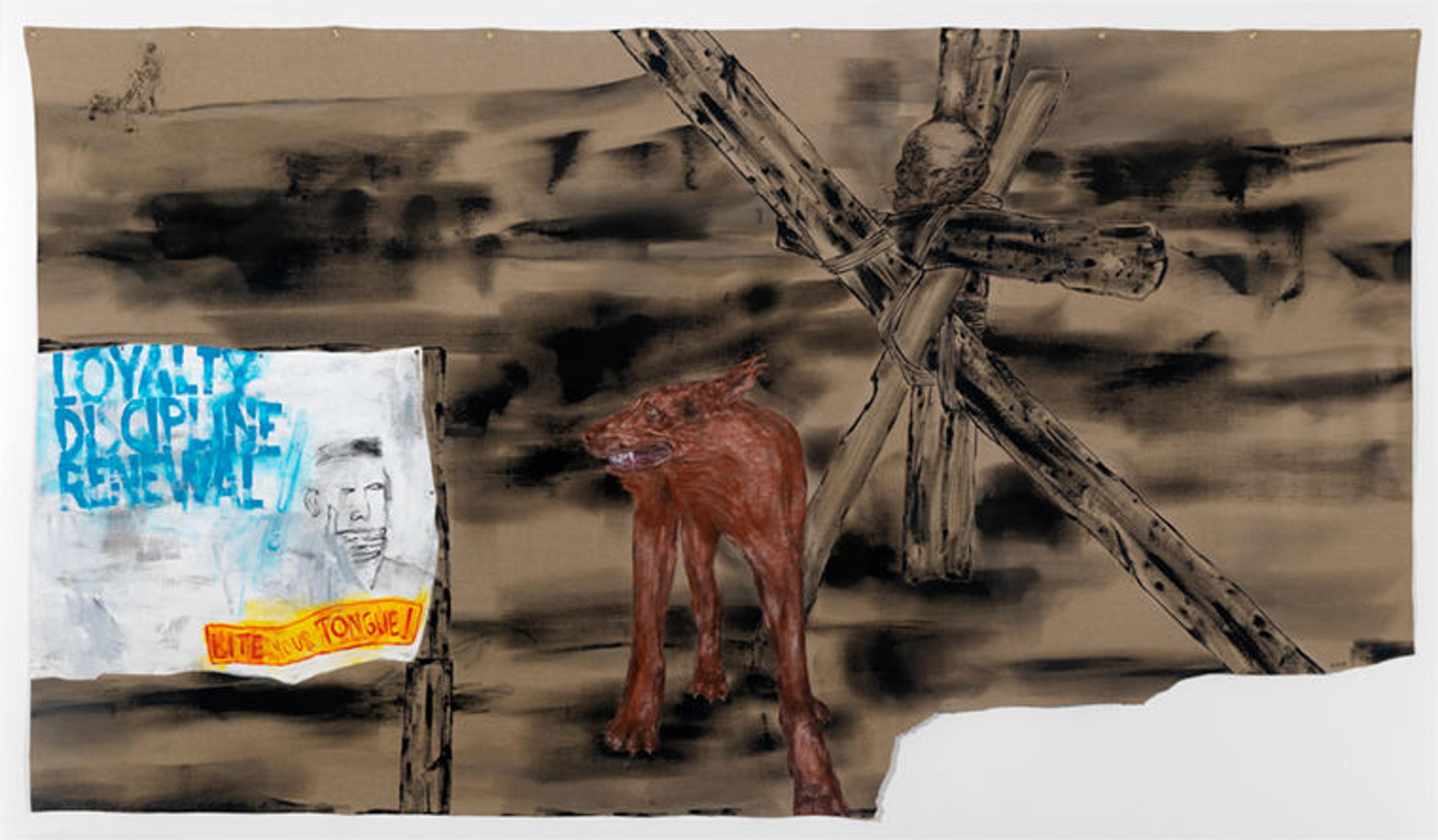

Left: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Bite Your Tongue, 2001. Acrylic on linen, 87 x 153 in. (221 x 388 cm). The Estate of Leon Golub, courtesy of Hauser and Wirth. Right: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). All Bets Are Off, 1994. Acrylic on linen, 89 5/8 x 96 3/8 in. (227.6 x 252.4 cm). Intended gift of Jon Bird

Will Fenstermaker: You're right, there's a lot of complexity in these late works. The final paintings are stunning in their fragmentation of space. All the elements interact but don't really cohere.

Kelly Baum: Up until this point, the large canvases had a coherent, recognizable narrative and a coherent, logical space. But in this late work, the compositions become more disjunctive. The effect is not unlike a collage, in which disparate images are combined together. They're not cohesive spatially the way the earlier paintings are. They're even less cohesive in terms of their story or narrative. There's a symbolism here that demands to be decoded.

Golub was diagnosed with cancer in 2000 or 2001, and it became increasingly difficult for him to paint on the scale of the Gigantomachies. It wasn't possible to continue in the very labor-intensive subtractive technique that he used throughout the eighties. So at the beginning of the 2000s, he started to produce more works on paper and, in the case of his paintings, he tended to add paint in relatively thin washes.

Will Fenstermaker: Did he ever work in collage?

Kelly Baum: No, not that I know of, but he spent his whole life looking at Spero's collages.

Will Fenstermaker: I can't help but think of the way that dogs are often depicted as harbingers of the apocalypse.

Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Bite Your Tongue, 2001. Acrylic on linen, 87 x 153 in. (221 x 388 cm). The Estate of Leon Golub, courtesy of Hauser and Wirth. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Kelly Baum: Definitely. There's a real apocalyptic sensibility. You see it in Bite Your Tongue, in the figure in the top-left corner, who's dragging another figure off into the distance. There's a sense here that Golub has painted the end of civilization, by which I mean the end of the idea of progress, betterment, and morality. It's not just that man has physically died in these paintings, but that he has died morally and ethically as well.

Will Fenstermaker: I suppose it's a warning of sorts. What can we learn here? What do you hope people viewing this show in the United States in 2018 will walk away thinking about the world today and art's role in contemporary discourse?

Left: Leon Golub (American, 1922–2004). Contemplating Pre-Columbian, ca. 2000. Oil stick on tracing paper, 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm). Intended gift of Jon Bird. Art © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Kelly Baum: One of Golub's main subjects was the theatrics of power. He was interested in how power is exercised, expressed, and, in particular, how it's abused. We're living in a moment when the abuse of power, especially by men, is also felt, concretely and deeply. It's the headline on every other paper, it seems. And Golub's subject, from the very beginning, was toxic, belligerent, abusive masculinity. He recognized the violence that men could do to one another, to women, and to others. We have a lot to learn from him.

Art-historically speaking, moreover, ours is a moment when the figure is enjoying a real renaissance in contemporary art. I'm an art historian of modern and contemporary art who's interested in contextualizing and historicizing contemporary art, and for me, Golub is an art-historical precedent for a lot of what we're seeing today. Some of the best artists working today are painting or collaging the figure in order to draw attention to sexual, racial, economic, social, and political injustice. Some of these artists, like Kara Walker for instance, have looked very carefully at Golub.

Will Fenstermaker: He's a kind of old master.

Kelly Baum: Yes, he was really of these artists' parents' generation. I think he's an interesting model—an art historical model and also a political model. He's somebody to acknowledge and celebrate for his place in the canon. He was very self-conscious about the way contemporary art is framed and informed by art history. He was also very smart about trying to join art and politics. And, of course, he was just a great painter as well.

Notes

[1] Quoted in a wall text in the exhibition Leon Golub: Raw Nerve.

[2] "Where the Camera Cannot Go: A Conversation with Leon Golub on Painting and Photography," in David Levi Strauss, Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics(New York: Aperture Foundation, 2003).

[3] The full passage reads: "To speak of reality becoming a spectacle is a breathtaking provincialism. It universalizes the viewing habits of a small, educated population living in the rich part of the world, where news has been converted into entertainment. . . . It assumes that everyone is a spectator. It suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world." Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2004), 110.

Editor's note: This interview has been condensed and edited from its original form.

Related Content

Leon Golub: Raw Nerve is on view at The Met Breuer through May 27, 2018.

Read more Curator Conversations on Now at The Met.

Will Fenstermaker

Will Fenstermaker is an editor and producer in the Digital Department at The Met.