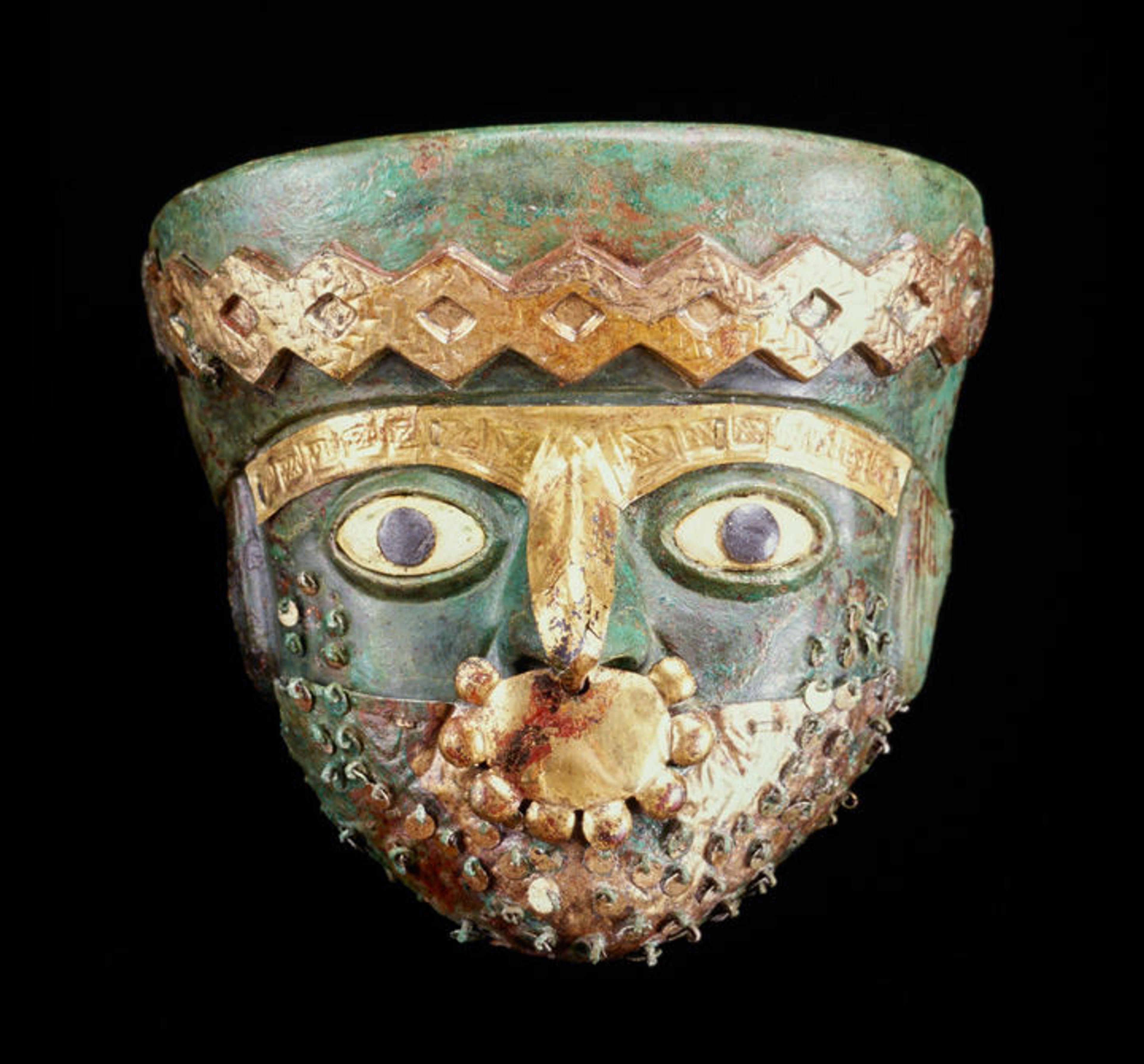

Burial mask, A.D. 525–550. Peru. Moche. Copper, gilded copper, shell, stone, H. 7/8 x W. 8 11/16 x D. 4 5/16 in. (20 x 22 x 11 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Perú. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Photo by Christopher B. Donnan

This blog article is also available in Spanish.

In the mid-sixth century, an unusually tall young man was laid to rest on Peru's north coast at a site now known as Dos Cabezas. His face was covered with a striking copper burial mask featuring wide-open eyes inlaid with shell and violet-colored stone, a guilloche-patterned headband, a T-shaped brow and nose band, an oval-shaped nose ornament, and small disks suspended by wire loops—perhaps representing a beard—all of gilded copper. Underneath the mask, the young man was wearing a rectangular gold nose ornament with a silver step-design border. He had three other nose ornaments, including one that masterfully captures the salient features of an owl in hammered gold sheet and strip that was intentionally compressed from the sides and placed in the mouth of the deceased. A miniature version of the funerary bundle was found in a compartment adjacent to his tomb.

Clockwise from top left: Nose ornament, A.D. 525–550. Peru. Moche. Gold, silver, H. 1 15/16 in. (5 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Perú. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Nose ornament, A.D. 525–550. Peru. Moche. Gold, H. 1 15/16 in. (5 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Peru. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Nose ornament, A.D. 525–550. Perú. Moche. Gold, stone, H. 1 15/16 in. (5 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Perú. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Nose ornament, A.D. 525–550. Peru. Moche. Gold, H. 1 15/16 in. (5 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Perú. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. Photos by Christopher B. Donnan

The young man's tomb is a reminder of the rich complexities of such works and their role in Moche society as revealed through scientific excavations. The upcoming exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, opening at The Met Fifth Avenue on February 28, draws upon these and other recent archaeological findings to illuminate the luxury arts in the lands between the two great imperial capitals of the ancient Americas: Cusco, the seat of the Inca state; and Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital now buried under Mexico City.

Golden Kingdoms is the result of an intensive four-year research effort that brought together art historians, archaeologists, and conservators from across Latin America, Europe, and the United States. With the generous support of the Getty Research Institute and the Getty Foundation, we gathered periodically in Lima, Los Angeles, and Mexico City to visit archaeological projects and study collections, and conducted additional research trips to Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Panama. The final selection of works includes more than 300 objects gathered from 52 lenders in 12 nations, including many that have been excavated in recent years, and others that have rarely, if ever, left their country of origin.

The exhibition's research team (including the author second from left and James Doyle, assistant curator of art of the ancient Americas at The Met, third from left) at the Museo del Templo Mayor in Mexico City, 2014. Photo by Kim N. Richter

The exhibition follows a specific historical and geographical path, tracing the development of goldworking in the Americas from its origins around 1000 B.C. in the Andes of South America, to its expansion northward into Central America, and finally to Mexico, where goldworking only came into its full flower after A.D. 1000. In the ancient Americas, artists and their patrons selected materials for luxury arts that could provoke a strong response—perceptually, sensually, and conceptually—and elevate the wearer and the beholder beyond the realms of the mundane. Rather than for tools, weapons, or currency, metals such as gold and silver were used primarily for ritual and regalia to express social status, political power, and religious beliefs. These and other materials used in luxury arts were also closely associated with the supernatural realm, for they were thought to be embodiments of divine power, emitted, inhabited, or consumed by gods.

Mouth mask with feline creature and human figures, 800–550 B.C. Peru. Cupisnique-Chavín. Gold, 5 3/4 x 8 3/8 in. (14.6 x 21.2 cm). Museo Kuntur Wasi, San Pablo. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú

Although the spread northward of goldworking provides the exhibition with its trajectory and narrative, this golden road passed through regions where gold was of little interest to the indigenous populations. At its core, Golden Kingdoms is inspired in part by this tension between what we now think of as inherent or universal value, and what was prized by the many civilizations that thrived in the Americas before the arrival of Europeans in 16th century. Jadeite, for example, was the ancient and enduring luxury material par excellence for the Olmecs and the Maya. And throughout the ancient Americas, fine garments of tapestry or feathers were among the most labor-intensive and highly prized luxury objects of all.

Mantle, 450–175 B.C. Paracas (Peru). Camelid fiber, H. 55 7/8 x W. 94 7/8 in. (142 x 241 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Alfred Paine Fund (31.501)

Indeed such variations bring to the fore the most challenging and broad-ranging research question driving this project: How can we discern and interpret indigenous ideas of value? Golden Kingdoms seeks to understand which materials were considered most precious to the Moche, the Incas, the Maya, the Aztecs, and other ancient American cultures, and how and why certain materials were selected and transformed into some of the ancient world's most spectacular works of art.

Plaque showing a seated king and palace attendant, A.D. 600–800. Mexico. Maya. Jadeite, H. 5 1/2 x W. 5 1/2 in. (14 x 14 cm). British Museum, London

Among the most fascinating works to be featured in the exhibition are those that began their lives in one part of the ancient Americas, only to be transported in ancient times to locations that are sometimes separated by thousands of miles—and hundreds of years—from where they were first created. As traditionally defined, luxury arts are not only of high value, they are also relatively small in scale and light in weight—qualities that make them worth transporting over great distances as royal gifts, trade items, or devotional offerings. An extraordinary Classic Maya jade plaque depicting a resplendent ruler seated upon a throne, for example, probably carved in what is now Guatemala between A.D. 600 and 800, ended up in the great central Mexican site of Teotihuacan, a city more than 600 miles away.

Another example of this migration of luxury art is one of the final works visitors will encounter in the exhibition, which also happens to be one of the oldest: a stone mask made by an Olmec artist in what is now the state of Guerrero, Mexico, around 800 B.C. The mask, however, was excavated at the Templo Mayor, the sacred center of the Aztec Empire, now under modern Mexico City and the focus of sustained archaeological research over the past 40 years. It had been preserved over the course of two millennia before it was deposited in an offering between A.D. 1469 and 1481.

Mask, ca. 800 B.C. (fabrication); A.D. 1469–81 (deposition). Mexico. Olmec. Hornblende hornfels, H. 4 1/4 x W. 3 3/8 x D. 1 1/4 in. (10.8 x 8.6 x 3.2 cm). Museo del Templo Mayor, Secretaria de Cultura—INAH, Mexico City

Over the course of the research, my co-curators—Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, and Kim N. Richter, senior research specialist at the Getty Research Institute—and I came to understand that, at a fundamental level, this exhibition is about the exchange of ideas in both the present and the past. Through study and conversation with colleagues, we collectively came to a new understanding about the role of these works in the exchange of ideas across regions. A project such as Golden Kingdoms allowed us to think about artistic exchange in the ancient Americas in a fresh way—unconstrained by today's national boundaries—in the process revealing networks across what were once, and are all too often now, considered separate traditions.

Many of the works in the exhibition come from funerary or devotional contexts, and it sharpens and deepens this question of how we, collectively and individually, select certain materials to create the most meaningful objects in our lives. At its heart, Golden Kingdoms is about an eternal, existential dilemma—one shared by all people at all times: How do you anchor the impermanence of existence in something more enduring?

These precious objects, these deeply resonant works, provide us with tangible connections to the great traditions of ancient Latin America. But they also provide us with opportunities to reflect on our lives today, and the way we, ourselves, accord value to certain materials, and how these materials express ideas. The objects in Golden Kingdoms, before they are anything else, are salutary reminders of our human desire to create anchors embodying belief, values, and permanence in an existence we know to be evanescent.

Related Links

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue from February 28 through May 28, 2018

Purchase a copy of the exhibition catalogue in The Met Store.