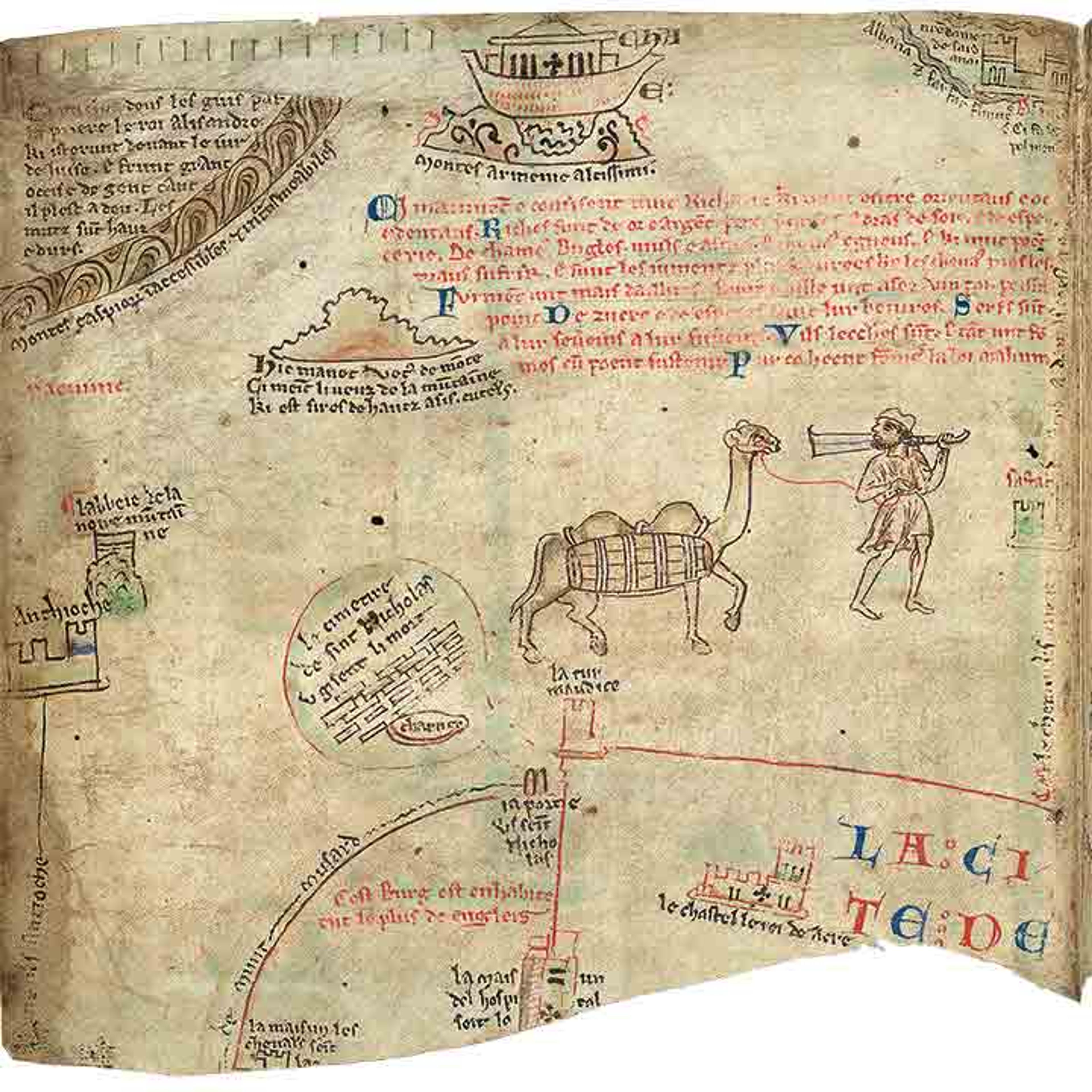

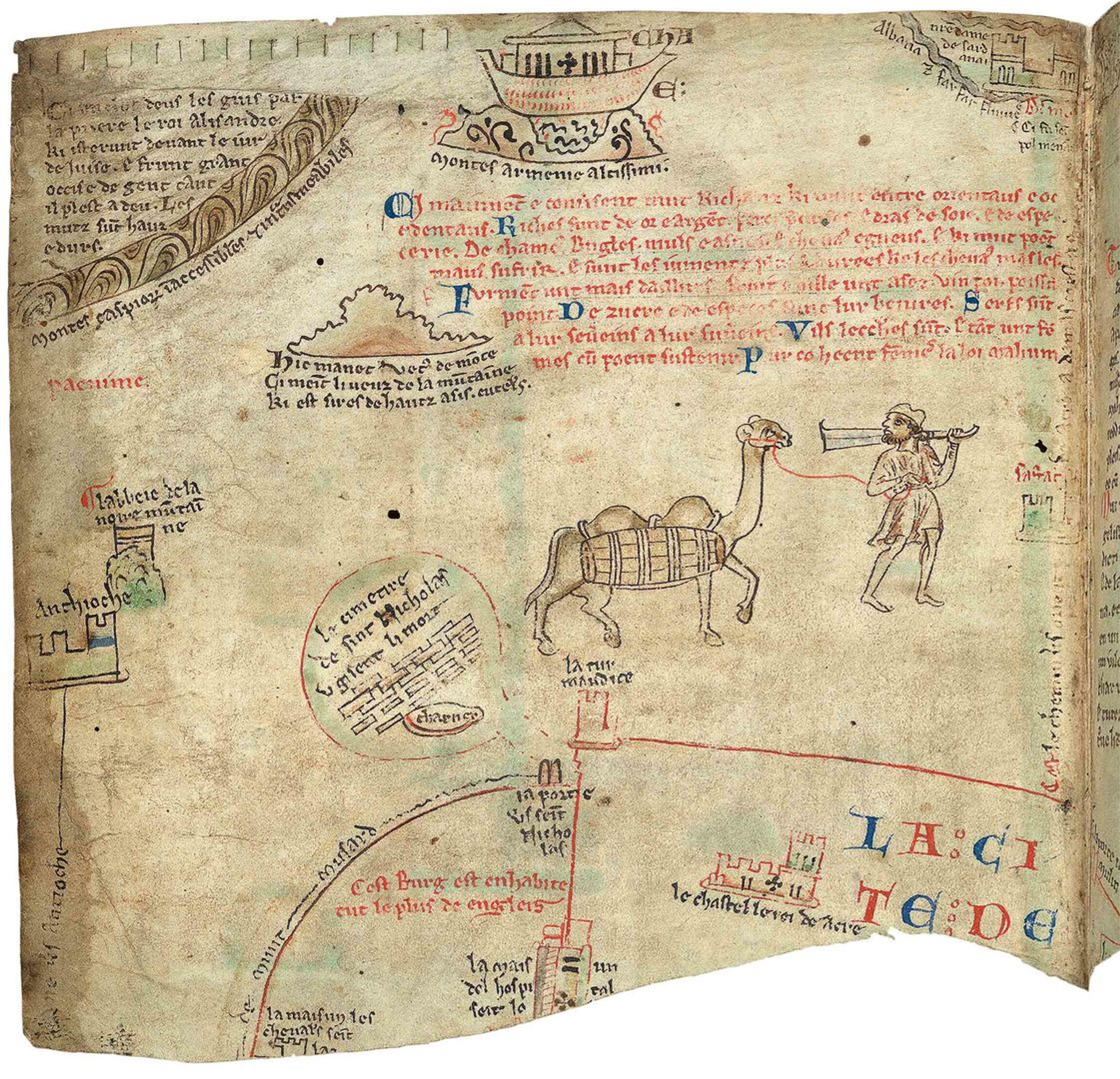

Map of the Holy Land with Armenia, ca. 1240–1253. Author: Matthew Paris (British, ca. 1200–1259). Made in Saint Albans, England. Opaque watercolor and ink on parchment; 151 folios, 14 1/4 x 9 3/4 in. (36.2 x 24.8 cm). Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom (ms 161)

In the first decades of the thirteenth century, the Benedictine monk Matthew of Paris interviewed a wide range of foreign travelers and dignitaries who were passing through the English Abbey of Saint Albans where he lived and worked, and incorporated their oral narratives into a history of the world from its beginnings through 1253. Filled with illustrations and maps, one of his versions of the Chronicle of World History (or Chronica Majora, to use its Latin name) contains a map of the Holy Land that is especially interesting for what it reveals about the geographic and symbolic position of Armenia in the medieval period.

This extraordinary map is one of the first objects that visitors encounter in the exhibition Armenia!, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 13, 2019. Produced by an English monk relying on information from Armenian travelers who had ventured all the way to England, the map succinctly captures the central focus of the exhibition, which is the first to situate medieval Armenian art and culture within a global context.

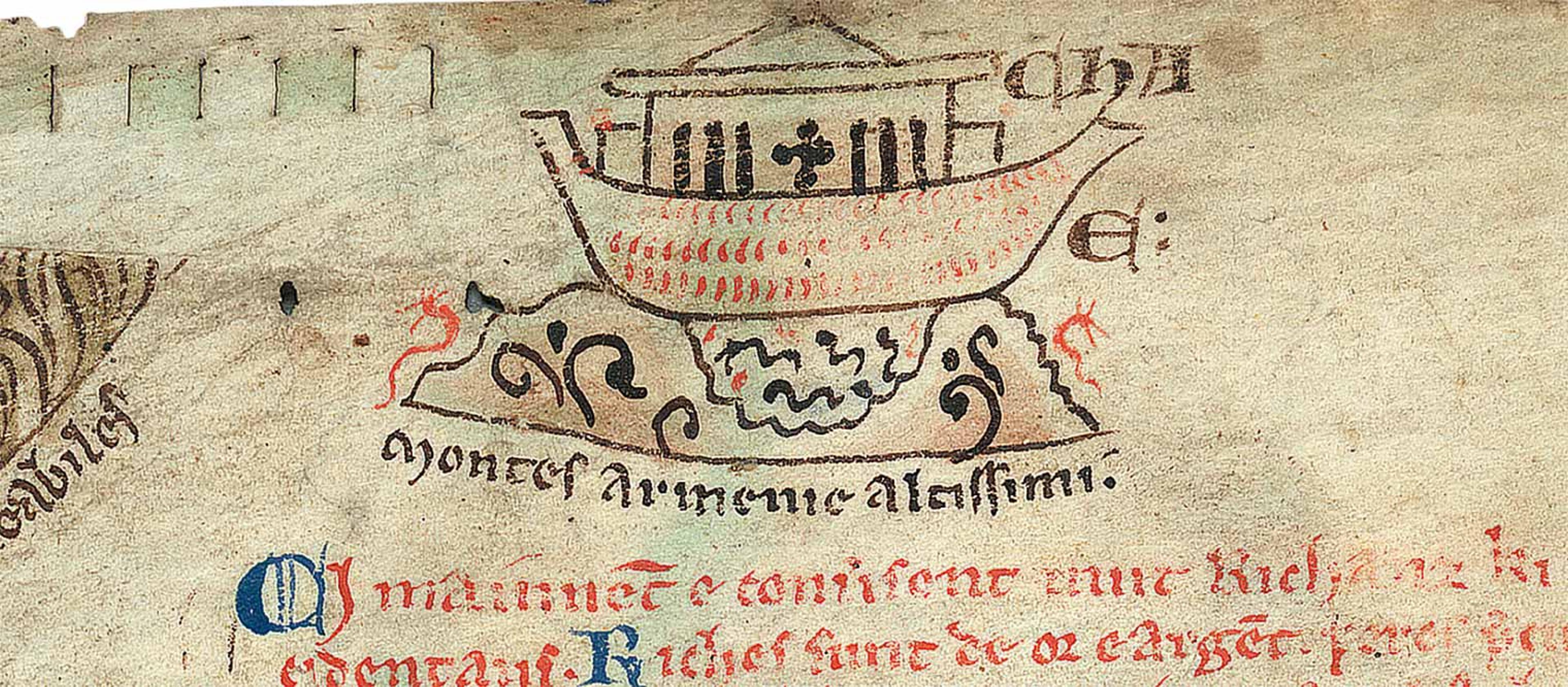

Map of the Holy Land with Armenia (detail)

Below a drawing of a mountain with two peaks, Paris has written montes Armeniae altissimi ("the highest mountains of Armenia"). A closer look at this detail suggests that Paris's representation of Armenia offers a concise depiction of the essential features of Mount Ararat, the highest peak on the Armenian plateau.

Mount Ararat and the Yerevan skyline in spring. Photo by Սէրուժ Ուրիշեան (Serouj Ourishian) [CC BY 4.0, from Wikimedia Commons]

Even today, Ararat's two dormant volcanic cones, referred to as Greater and Little Ararat, dominate the views south from Yerevan, the capital of the modern Republic of Armenia. We can see them in Paris's schematic rendition, where he has drawn a single mountain with two peaks, one much broader than the other.

But what's going on with the boat on top of the mountain? Here, we need the text of the Chronicle. According to the author, a group of Armenians who visited Saint Albans in 1252 described their homeland as "about thirty days' distance from Jerusalem. . . . The Ark of Noah . . . stands on the summits of two very high mountains . . . infested by hosts of poisonous snakes and dragons." Looking at the drawing, we can almost imagine the thirteenth-century Armenian visitors describing the distinctive profile of Mount Ararat for the English monk, who then balanced the Ark on its two peaks.

For these medieval travelers from afar, Mount Ararat was much more than a geographic anchor in the landscape of their homeland. It was also potent symbol of their origins. Mount Ararat had been associated with Noah's ark since the Book of Genesis (Genesis 8:4). The holy mountain affirmed the Armenians' identity as the people of the ark, a tradition that went back to the fifth century, when the historian Movses Khorenats'i described the Armenians as the descendants of Hayk, whose ancestor was Noah.

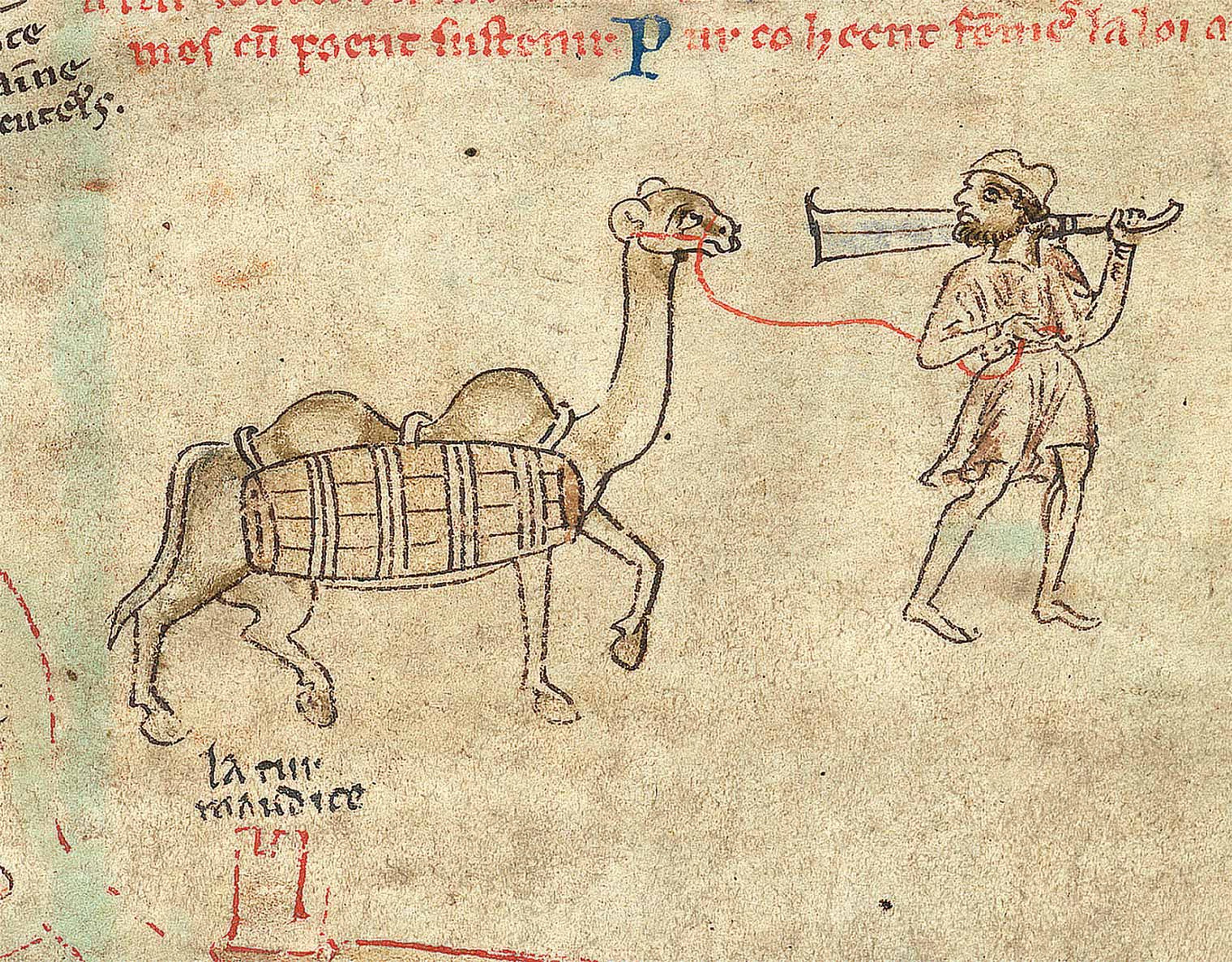

Map of the Holy Land with Armenia (detail)

Paris's drawing also alludes to Armenia's strategic location at a critical position between the East and the West. The map is oriented with its top to the east, so Armenia anchors the easternmost edge of the known world, supporting Paris's claim that their land "extended to India." Occupying a mountainous zone between the Black and Caspian seas, Armenia straddled important trade routes traditionally referred to as the Silk Road, a role alluded to in the map by an armed man leading a camel fitted for long-distance trade (above).

Armenians everywhere shared a common language and religious beliefs, both rooted in their early adoption of Christianity as their state religion. The story of their conversion to Christianity is a recurring theme that appears throughout the centuries in works of many different media.

The story begins early in the fourth century AD, when Gregory the Illuminator converted the Armenian king Tiridates the Great (r. 287–ca. 300) and his people, giving rise to their claim as the first Christian nation.

Four-sided stela, 4th–5th century. Armenian. Made near Vank' Xaraba. Tuff, 69 6.8 x 15 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (177 x 40 x 40 cm; weight 992.1 lb (450 kg). History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan (830)

This stela, one of the earliest surviving works of Armenian Christian art, depicts a haloed Saint Gregory the Illuminator (above left). On one side (above right), he is faced by an animal-headed man in courtly robes, who is likely an image of King Tiridates. The king's animal head signifies his descent into madness, when, consumed by love, he murdered the beautiful young nun Hripsime for spurning his advances. Summoned from prison, Gregory the Illuminator cured the king of his malady, which prompted Tiridates to recognize the power of Christianity.

Etchmiadzin Cathedral. Photo by Hrair Hawk Khatcherian and Lilit Khachatryan. From the exhibition catalogue, Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages, 246

Tiridates's declaration of Christianity as the state religion of the Armenian people in the early fourth century predated its official adoption by the Roman Empire by several decades. The new religion assumed physical form with the founding of the cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin, the seat of the Armenian Church. According to tradition, Saint Gregory the Illuminator founded the first church of the Armenians at Etchmiadzin, a site located on the plains north of Mount Ararat, after a dream in which he saw Jesus Christ descending from the heavens, "carrying in his hand a golden sledge hammer."

Altar frontal, 1741. Armenian. Made in Isfahan. Gold thread, silver thread, and silk thread on silk, 26 5/8 x 38 3/8 in. (67.5 x 97.5 cm). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, Armenia (626)

This legend of the founding of the pontifical see is brilliantly depicted in an embroidered altar frontal produced in New Julfa, an Armenian enclave founded in the Persian capital of Isfahan by Shah Abbas I (r. 1587–1692), who placed Armenian merchants in charge of all trade within the Safavid Empire.

In the textile, Jesus Christ emerges from a fiery cloud together with God the Father and the Holy Spirit. Wielding his hammer, he directs Gregory the Illuminator, who stands below dressed in pontifical robes, to found his church on the site of Etchmiadzin, which translates as "the Only Begotten of the Father [who] came down [to earth]." The visionary character of the scene is conveyed by an angel wearing red, who directs Saint Gregory's gaze towards the heavens. Kneeling at Gregory's feet is King Tiridates, who wears a crown on his animal head. Following Tiridates' appointment of Gregory the Illuminator as the leader of the newly founded Armenian Church, a vibrant artistic tradition emerged in the shadows of Mount Ararat.

In the centuries that followed, the Armenians developed a unique visual identity, rooted in a special reverence for the word of God. Using an alphabet developed in the early fifth century by the scholar and cleric Mashtotsʻ, the Armenians excelled at conveying the power of the sacred word, especially in the form of lavishly illuminated sacred texts, most notably the Four Gospels. Strikingly original, these books stand out as a special feature of Armenian artistic production, offering memorable images that blend established traditions with inflections from other cultures and the unique visions of their creators.

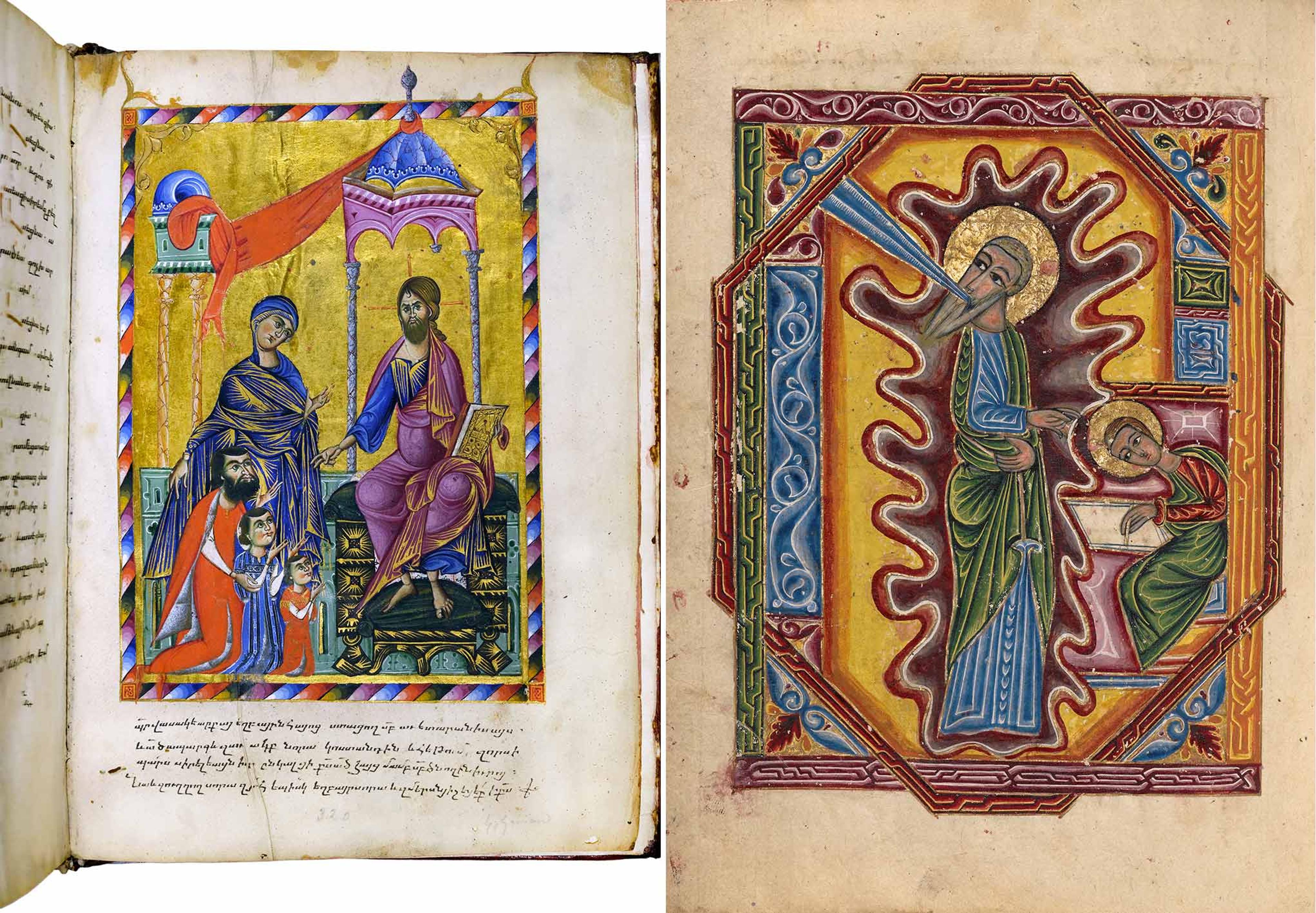

Left: Second Prince Vasak Gospel Book, 1268–1285. Armenian. Made in Cilicia. Ink, tempera, and gold on parchment; 323 folios, 10 1/4 x 7 7/8 in. (26 × 20 cm). Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem (ms 2568/13). Right: Gospel Book, 1615. Armenian. Made in Isfahan. Tempera, gold, and ink on paper; 246 folios, 9 1/8 x 6 3/4 in. (23 x 17.1 cm). J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (MS Ludwig II.7)

Pulsing with expressive figures, vivid colors, and animated letters, these manuscripts represent some of the most imaginative visual representations of Christian faith produced in the medieval period. What makes these material expressions of devotion especially compelling is the various ways in which Armenian scribes, illuminators, and patrons responded to their position at the crossroads of different civilizations and systems of belief. In thirteenth-century Armenian manuscripts from the Kingdom of Cilicia (founded along the mountainous southeastern coast of modern Turkey), motifs from western art are increasingly apparent, as Franciscan and Dominican friars established close contacts with Armenian royal families. Seventeenth-century scribes and illuminators working in New Julfa retained the distinctive palette and format of Armenian gospel books, but make creative use of ornamental and expressive motifs from Persian decorative traditions.

Armenia! offers a fascinating vision of a people negotiating a complex world. Often dominated by Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman Empires in the west, and by the Persian Parthian, Sasanian, and Safavid Empires in the east, Armenians persevered in developing a distinctive visual tradition. From the shadows of Mount Ararat, their historical homeland, Armenians carried their unique visual language out into the world, maintaining and adapting their artistic traditions as they forged new communities along trade routes both east and west. The metalwork, architecture, manuscripts, sculpture and textiles featured in this exhibition linked Armenians with each other and with a broader world. While Mount Ararat stands at the symbolic heart of the land that shaped their identity, Armenians transformed its spiritual shadow into works of art with an enduring expressive power.

Related Content

Armenia! is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 13, 2019.

Visit the places mentioned in this blog post on The Met's Interactive Map of Armenians in the Medieval World.

View the galleries in the exhibition's digital walkthrough.

Listen to the Audio Guide for the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available at The Met Store.