Art as Influence and Response: A First Look at World War I and the Visual Arts

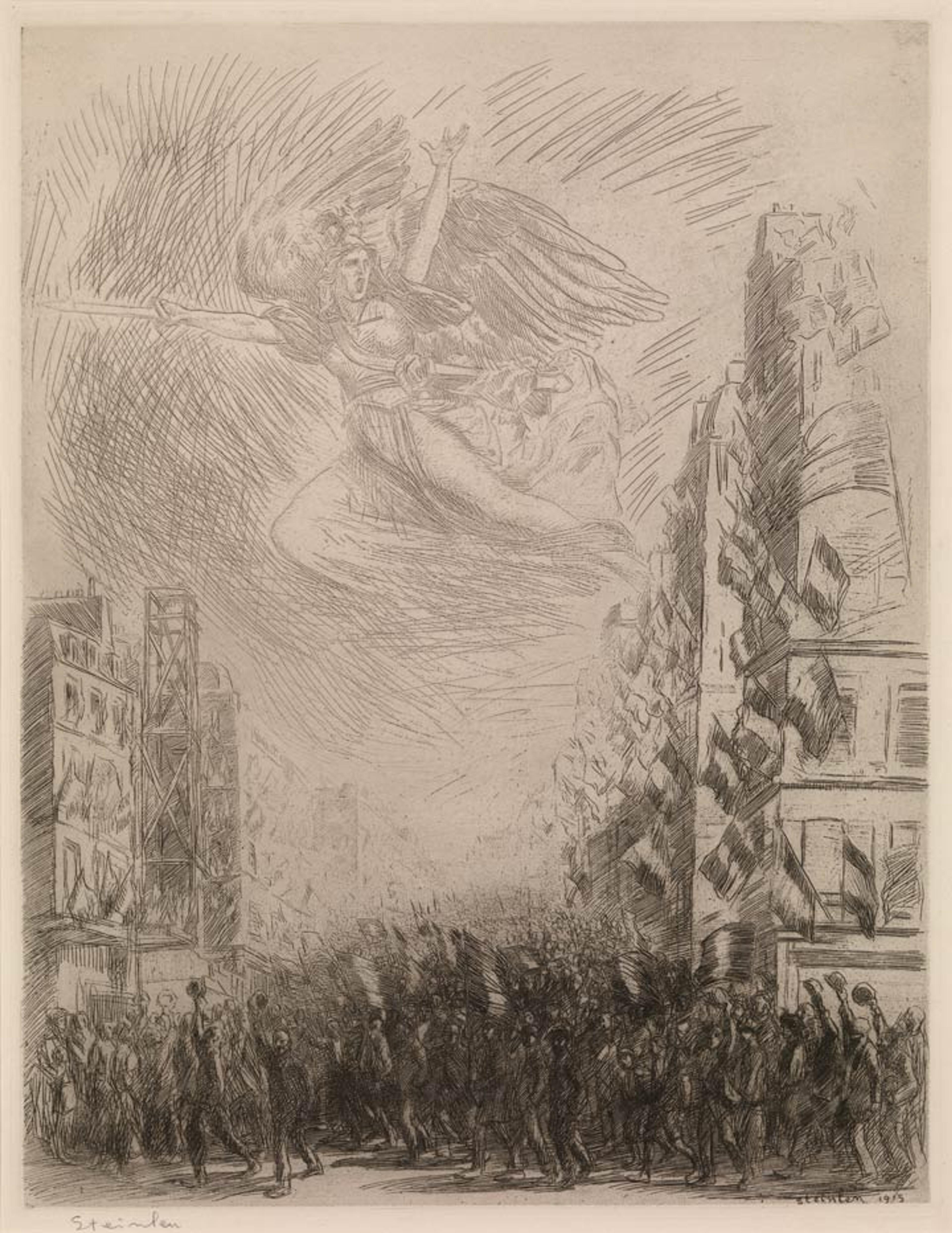

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Mobilization, or La Marseillaise, 1915. Etching, sheet: 25 11/16 x 19 11/16 in. (65.2 x 50 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.58.31)

«Organized to commemorate the centennial of World War I, World War I and the Visual Arts features more than 130 works—mainly works on paper—drawn from The Met collection and supplemented with select loans. The exhibition showcases some of the ways in which artists both reacted to and represented the horrors of modern warfare and its aftermath. As visitors move through the galleries, so does the exhibition move chronologically—from the mobilization in the beginning of August 1914 to the 1918 armistice and the decade that followed.»

Like their countrymen, many artists, writers, and intellectuals initially welcomed the war for a range of reasons: some because of nationalist sentiments or a sense of patriotic duty; others had a desire to experience an "adventure" they assumed would be over in a few months, if not weeks; and still others because of a mistaken belief that, after what they viewed as a final and necessary conflict ended, oppressive political systems (often dynasties whose various rulers were related by blood or marriage) would disappear and a more peaceful, spiritual, and anti-materialist era would begin.

While some artists, such as George Grosz—who had long rejected militarism and nationalist sentiment—rejected the war from the beginning yet were conscripted into service, and others, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, "involuntarily voluntarily" enlisted with the goal of gaining some control over their placement, many more figures, including Max Beckmann and Otto Dix, enthusiastically enlisted. In the case of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, he strongly advocated for his country, Italy, to enter so that he could join the army and be a part of the battle.

Max Beckmann (German, 1884–1950). Two Officers, 1915. Drypoint, 4 1/2 x 6 7/8 in. (11.4 x 17.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Reba and Dave Williams Gift, 1999 (1999.232.2). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

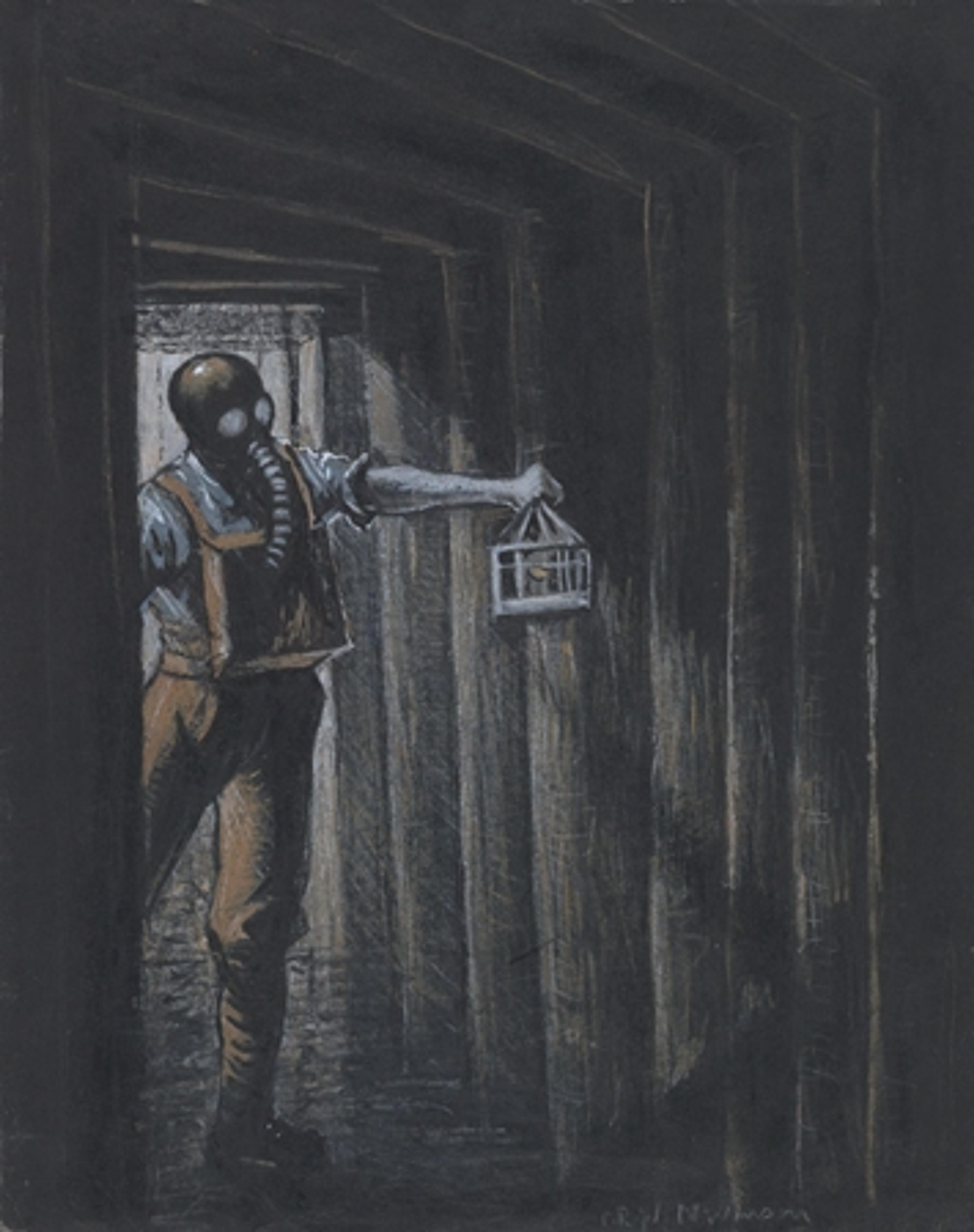

Because there were a large number of artists who experienced combat firsthand, either as soldiers, medics, or war artists documenting life at the front (with many suffering severe injuries or death), several figures produced work either at the front or based on their experiences engaging in or witnessing combat. In response to the unprecedented turmoil and trauma resulting from the war, many artists' reactions changed dramatically over a short period of time as fierce nationalism, enthusiasm for regalia and combat, and even optimism for a more democratic future frequently morphed into mournful reflection, feelings of loss and betrayal, pacifism, and rage—directed not only at the institutions deemed responsible but also at their own complicity.

Artists searched for an appropriate language to express the chaos and carnage that resulted from modern industrial warfare, reevaluating subject matter, techniques, materials, and styles, as well as their positions and responsibilities as cultural producers. While some figures employed a modernist approach that drew from avant-garde experimentation begun before the war or was born in reaction to its carnage, others embraced a more traditional, figurative style; still others drew elements from both approaches or moved between styles for a variety of reasons.

Represented in the exhibition are several generations of artists, ranging from those who had gained fame in the 19th century such as Pierre Bonnard, John Singer Sargent, and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, to younger figures who were still finding a voice such as Otto Dix, who left art school to enlist in the German army. Those working in applied and commercial arts also revealed a variety of approaches; some work was commissioned by the government or other organizations to support the war effort and charities, while other propaganda—sometimes the most inflammatory—was independently produced and distributed as periodicals, postcards, and posters in order to boost morale and demean the enemy.

Left: Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889–1946). Tunnellers, 1916. Ink, gouache, graphite, and crayon, sheet: 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm). Collection of Johanna and Leslie Garfield

As the war progressed, artists expressed a variety of emotions. Despite initially supporting the war effort by creating works for periodicals such as Kriegszeit (War Time)—the bellicose art journal founded by the publisher and gallery owner Paul Cassirer in the summer of 1914—by 1916 artists such as Ernst Barlach and Käthe Kollwitz had begun making elegiac works about the devastation experienced by families and communities. By the middle of the war Cassirer renounced his nationalist sentiments and became a pacifist, and in April 1916 replaced Kriegszeit with Der Bilderman (The Picture Man), a journal in which artists called attention to war's carnage and advocated for peace.

By contrast, the work of Beckmann, Dix, and Grosz expressed a profound rage at the societies, institutions, and individuals they viewed as promoting and profiting from war. Many of these artists used the same techniques and means initially developed in support of the war, such as propagandistic imagery that could be reproduced in a variety of media and at different price points. Because prints could be distributed more widely and at a lower cost than unique works, they were especially effective at influencing public opinion and could be made available to large audiences. Most importantly, by reproducing the images in periodicals, pamphlets, posters, and other such publications, the art—and the message—could reach even more people.

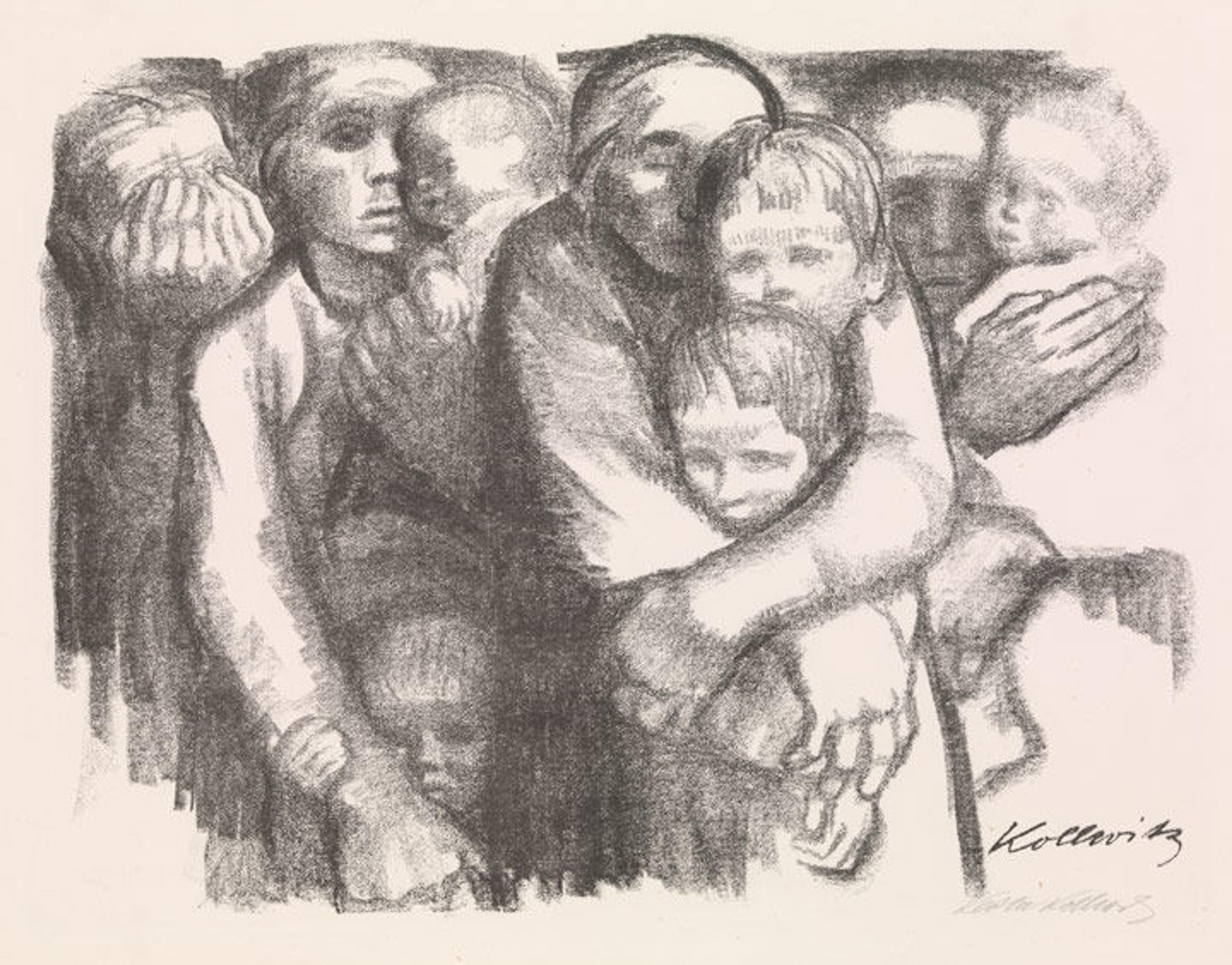

Many publishers also used art to commemorate the war by producing portfolios, many of which were released on the 10th anniversary of its beginning or end, whose subject was its enduring trauma. Among the most celebrated of these works are Kollwitz's Krieg (War) (1921–1922, published 1923) and Otto Dix's Der Krieg (The War), which was published in 1924, a moment declared as "the year against war." In Kollwitz's lithograph Mütter (Mothers), the women and children—both of whom are shown in different stages of life—huddle together, linking their bodies to form a solid structure that fills the composition. Kollwitz drew herself in the center, with her eyes closed and her arms wrapped protectively around her two sons.

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945). Mothers (Mütter), 1919. Lithograph, sheet: 20 3/4 x 27 5/8 in. (52.7 x 70.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928 (28.68.3)

She wrote about the work in a diary entry of February 1919 with great pride and tenderness: "I have drawn the mother who embraces her two children, I am with my own children, born from me, my Hans and my Peterchen." Her younger son, Peter, was enticed by the flurry of patriotic sentiment and war enthusiasm, and volunteered for combat at the outbreak with his mother's assistance, as he was underage. He died in October 1914, at age 18, while fighting in Belgium.

Dix's Der Krieg, comprising five suites of ten images that depict horrors unique to trench warfare and its aftermath, is widely regarded as one of the 20th century's most powerful artistic statements on war and the artist's greatest graphic work. The images of wounded and fallen soldiers, scarred battlefields, bombed towns, and other nightmarish situations highlight the horrors of modern warfare and man's inhumanity. In addition to his own memories, Dix referred to photographs of dead and disfigured bodies and corpses from the morgue, as well as Goya's Disasters of War series and earlier German works by Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach, in order to capture the raw grisliness and brutality of the war.

This exhibition provided the opportunity to present works from the collections of several curatorial departments; many of these had not been shown recently, and some had never been exhibited at the Museum before. Rather than offering a particular style or focused view, as discussed in this post, the show presents a diverse group of works that identify an array of approaches, materials, and techniques used by those working in both fine and applied art.

Right: Paul Iribe (French, 1883–1935). After the Execution, cover of Le Mot, vol. 1, no. 5, January 9, 1915. Color woodcut and letterpress, 16 7/16 x 11 x 3/16 in. (41.8 x 28 x 0.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1969 (69.503[5])

Featured alongside more celebrated artists is a collection of illustrators who may be less known—Guy Arnoux, Edouard García Benito, Thomas Theodor Heine, Paul Iribe, and Jean-Emile Laboureur—as well as work by anonymous figures such as the designers of the two toiles de guerre (war toiles) who updated the traditional French printed cotton fabrics to make them topical.

Created during World War I, these textiles were intended to boost patriotism. They incorporated various national symbols, often with roots in ancient classicism; these motifs—wreaths and trophies of weapons for victory, fasces for strength in numbers, Phrygian caps for freedom, cockerels for France, and Marianne (the classically dressed female figure) for reason, liberty, and the personification of the French people—were combined with images evoking modern industrial warfare (such as contemporary guns and helmets) as well as references to specific battles, such as Verdun, rendering the toiles both current and traditional, topical and nostalgic.

Unknown designer. Toile de guerre (war toile), ca. 1916. Printed cotton, 17 1/2 × 16 1/4 in. (44.5 × 41.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Eddystone Manufacturing Company, 1917 (17.132.2)

In addition to prints, drawings, photographs, illustrated books, posters, periodicals, and trading cards from the Museum's celebrated Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, World War I and the Visual Arts includes other materials such as helmets (whose prototypes were designed at The Met by former Arms and Armor curator Bashford Dean), medals, and examples of trench art—all of which work together to provide the broadest possible scope of how the visual arts were affected by and contributed to the war experience.

Related Links

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Bashford Dean and the Development of Helmets and Body Armor during World War I"

Jennifer Farrell

Jennifer Farrell is a curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.