«In China, paintings that tell stories have flourished as powerful vehicles for both didactic messages and self-expression since the fourth century. Such paintings typically offer either continuous, multiscene illustrations presented in long handscrolls, or monoscenic compositions that evoke an entire story with a single iconic episode.

But we also find generic landscape, flower-and-bird, and figure paintings that—despite the absence of narrative imagery—tell vivid stories through appended inscriptions.» The text and the image are each a self-contained work of art, but together they construct a mental landscape that is greater than the sum of its parts.

A group of works representing this distinctively Chinese practice from the 13th century to the present is featured in the exhibition Show and Tell: Stories in Chinese Painting, on display in galleries 210–216 through August 6, 2017.

Left: Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707). Bamboo in Wind and Rain, ca. 1694. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Hanging scroll, ink on paper, image: 87 3/4 x 30 in. (222.9 x 76.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward Elliott Family Collection, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1984 (1984.475.2)

Chinese painters like to relate stories from the past that deepen the significance of their works. On his 17th-century painting of bamboo, the painter Shitao (1642–1707) records the comments of Su Che, an 11th-century scholar who once praised a friend's painting on the same subject:

Wen Tong [1018–1079] painted bamboo in ink monochrome and took pride in it. When a guest was thrilled at the sight of it, Su Che [1039–1112] explained, "[Wen] dallies amid bamboo in the morning, stays in the company of bamboo in the evening, drinks and eats amid the bamboo, and rests in the shade of bamboo. Thus he has observed innumerable forms of bamboo." Only after one has done this, can he exhaust its constantly changing appearances. . . .

After invoking the conversation of this fabled circle of friends, Shitao concludes the inscription by endorsing Wen Tong's creative method of total immersion and proclaiming artistic affinity to the earlier master; in the painting, the young bamboo on the left curves toward its tall counterpart, as if bowing in homage.

Another painter, Wang Jun (1816–after 1883), relates stories from the more recent past in an album of paintings that depicts 10 topographical sites associated with the eminent scholar-official Ruan Yuan (1764–1849) with a focus on the Ruan family properties in Yangzhou.

Wang Jun (Chinese, 1816–after 1883). "Hall of Ten Thousand Willows," inTen Sites Associated with Ruan Yuan, 1883. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Leaf from an album of 10 paintings, ink and color on paper, each leaf: 11 x 13 1/4 in. (27.9 x 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Julia and John Curtis, 2015 (2015.784.10)

Wang gives each picture an inscription that tells the story of the place, thereby converting the landscape album into an informative biography of the man. On one leaf, which shows a lakeside cottage surrounded by lush willows expanding into the misty distance, Wang quotes a passage from Ruan Yuan's anthology:

My family's thatched cottage by Lake Pearl was flooded by the overflow of Lake Hong. In the spring of the 19th year of the Daoguang era [1839], I built dikes around some 82 acres of lowland and planted 20,000 Jiangzhou willows throughout the place. Since there were already hundreds of old willows from former times on the property, I wrote "Hall of Ten Thousand Willows" on the front gate of the estate. Now, back on my ancestral land, I can practice farming and enjoy fish-watching, far from urban worldliness. . . .

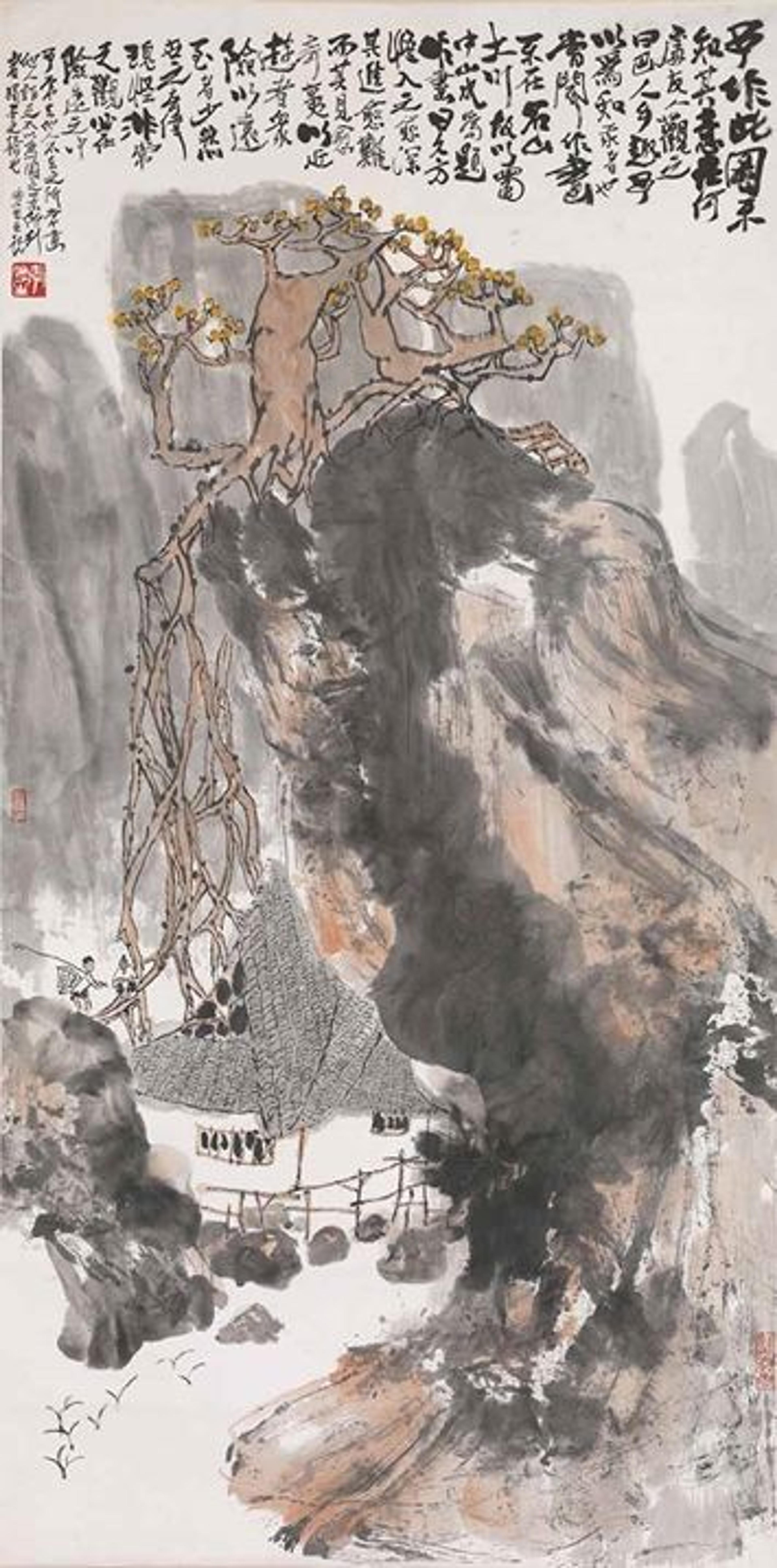

Wang Jun (Chinese, 1816–after 1883). "Gingko Trees," in Ten Sites Associated with Ruan Yuan, 1883. China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Leaf from an album of 10 paintings, ink and color on paper, each leaf: 11 x 13 1/4 in. (27.9 x 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Julia and John Curtis, 2015 (2015.784.10)

In another painting, Wang Jun depicts a pair of monumental gingkos that flank a stone path. The deeply pitted, gnarly knots are natural ornaments; and the moss-dappled bark and webs of young twigs brim with vivacity. The artist introduces the trees with an inscription in his own voice:

In the ninth year of the Jiaqing era [1804], Master [Ruan Yuan] carried out his father's admonition to build the family temple in the Xingren district in the older part of Yangzhou. There he planted two gingko trees with his own hands. After 70-some years, their branches and leaves have flourished and become the best of their kind, as hoped. In the guichou year of the Xianfeng era [1853], when the city was occupied by rebels from Guangdong, both the temple and the trees survived intact. I therefore thought of the line in Du Fu's [712–770] poem, "it must have been sustained by divine power," which may well be applied to these trees.

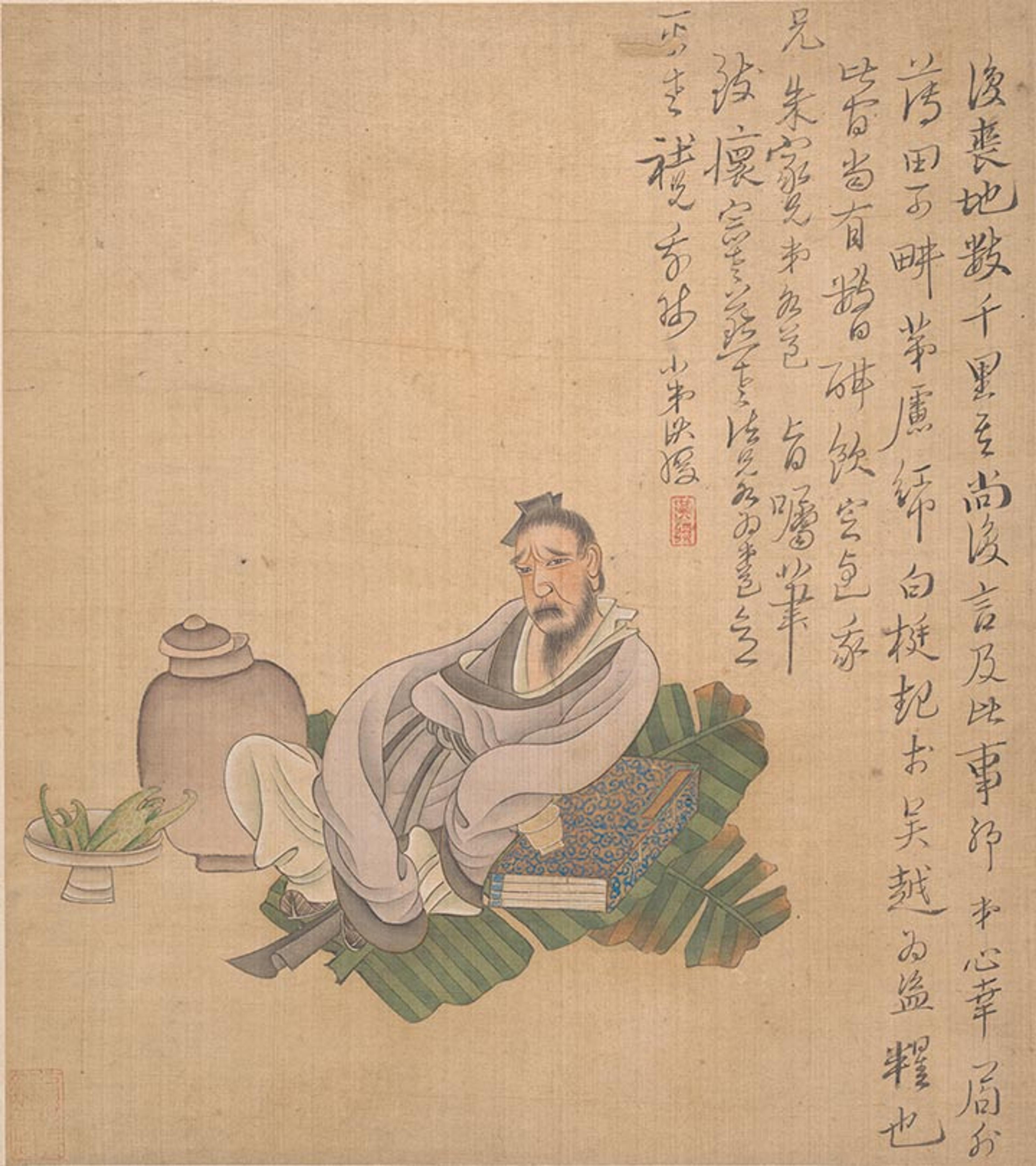

Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). "Self-image," in Figures, Flowers, and Landscapes, ca. 1633. China, late Ming (1368–1644) to early Qing (1644–1911) dynasty. Leaf from an album of 11 paintings, ink and color on silk, image: 8 3/4 x 8 5/8 (22.2 x 21.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wan-go H. C. Weng, 1999 (1999.521)

Artists talk about themselves too. An inscription appended to Chen Hongshou's [1599–1652] generic depiction of a dejected scholar in a drunken stupor transforms the work into a self-portrait. With flushed cheeks and droopy eyes, the man slumps on a stack of books, and the wobbly jar and tilted vessel of fruit suggest his distorted vision of the surroundings. The inscription, a letter to a friend, reveals that this is the artist himself, lamenting the loss of vast territories along China's northern borders to the invading Manchus, and fretting about local disturbances:

Again we have lost several thousand li of [national] territory. Shall we talk about this yet again? I feel lucky to have some land to farm far from there, but worry that armed rebels rising up in the Wu and Yue regions [modern Jiangsu and Zhejiang] will rob my granary. Meanwhile, there is still time to drink to our hearts' content, and I shall certainly come visit you. The Zhu brothers have all asked me to send their regards. Please remember me to the venerable Zong [Zhang Dai, 1597–1679] and Yan [Zhang Yanke, active mid-17th century]. To my erudite friend Ping [Zhang Pingzi, active mid-17th century].

The warm regards that the woebegone painter expresses on behalf of his friends, and his anticipation of future drinking parties, reveal a cheerful side of his personality that belies the image.

Left: Li Huasheng (Chinese, b. 1944). Rustic Scene, 1982. Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, image: 53 1/2 x 26 1/2 in. (135.9 x 67.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Jerome Silbergeld and Michelle DeKlyen, 2013 (2013.1107)

In an eerily bold landscape by Li Huasheng (b. 1944), a massive tree atop a tall bluff sends a cascade of aerial roots down to a gable-roofed pavilion. This almost surreal sight may not be pure invention, but rather a subjective re-creation of something the artist actually saw at an obscure place in his native Sichuan Province. Seeking out such singular sights was essential to his creativity, as he explains in his inscription:

To common and nearby places, travelers come in crowds, but few attempt the precarious and remote. Yet the grand, extraordinary, and strange sights of the world are always found in precarious and remote places. I tend to travel where others do not and to paint what others dismiss as unsuitable for painting. The places I go only have single-plank bridges [for lone travelers].[1]

In an intimate voice, the painter describes a creative process that requires both physical and mental detachment, while the abstract rendering of the towering boulder in the foreground reflects his intellectual detachment from visible phenomena.

In his provocative remake of The Classic of Mountains and Seas, an ancient encyclopedia describing a myriad of mostly mythical creatures in exotic locales, Qiu Anxiong (b. 1972) adopts the woodblock print–illustrated format of his model, but addresses current issues in an allegorical manner using words and images of his own.

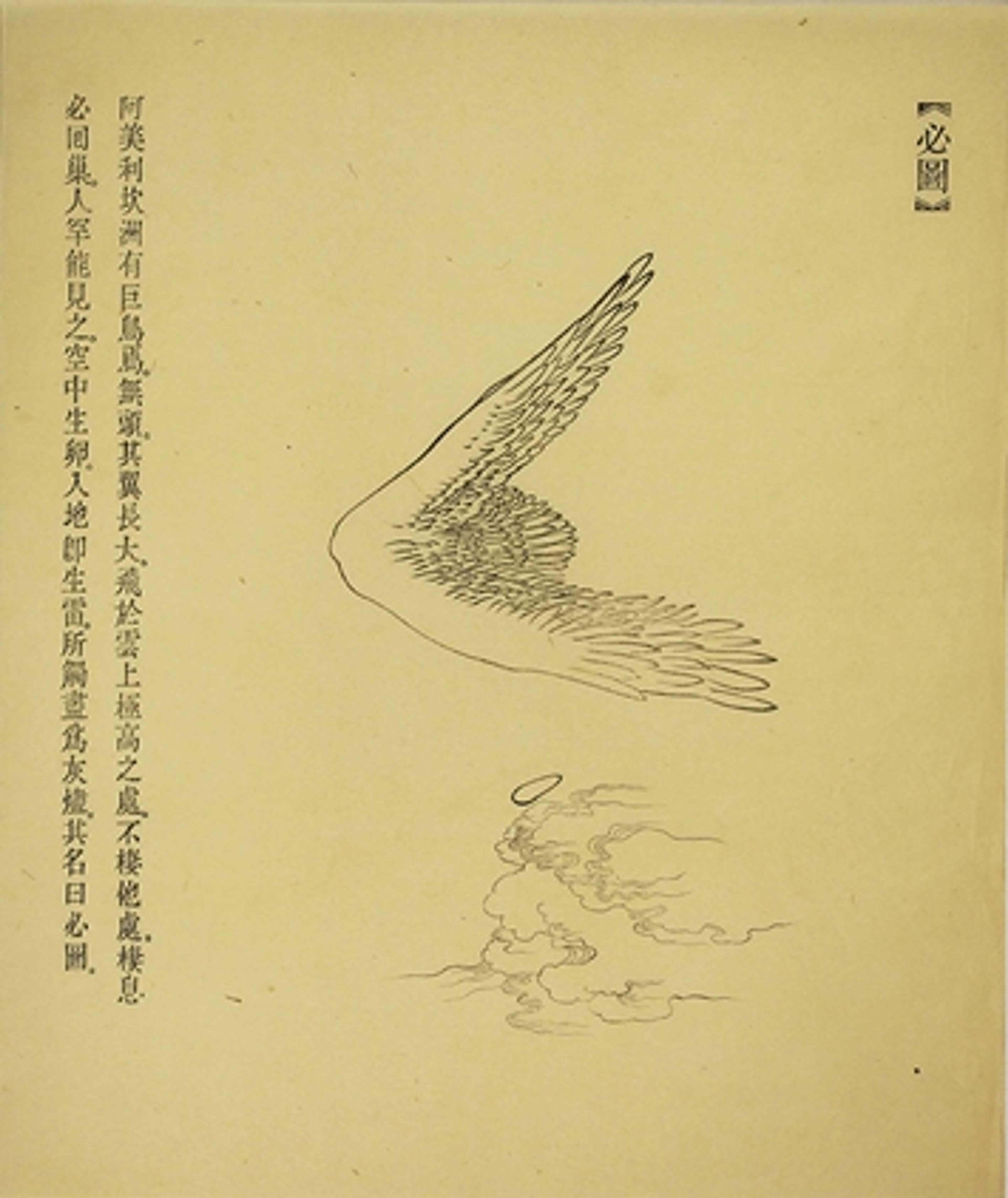

Right: Qiu Anxiong (Chinese, b. 1972). "Bitu" [B-2 Bomber], inNew Classic of Mountains and Seas I, 2008. Leaf from a portfolio of 12 woodblock prints, ink on paper, each leaf: 19 3/4 x 16 1/2 in. (50.2 x 41.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2013 (2013.944a–l)

The artist gives each picture a title that is a close phonetic equivalent of the creature's name in English, as well an inscription that describes its physical and behavioral traits. One picture, showing a headless creature with widespread feathery wings soaring above the clouds, is titled "Bitu," an allusion to the B-2 bomber. The inscription reads:

On the American continent there is a species of giant bird with no head. Its wings are long and large, suitable for flying high above the clouds. It does not rest anywhere but its nest. People can rarely see it. It lays eggs in the sky that thunder when they hit the ground, turning everything they touch into ashes. It is called "Bitu."

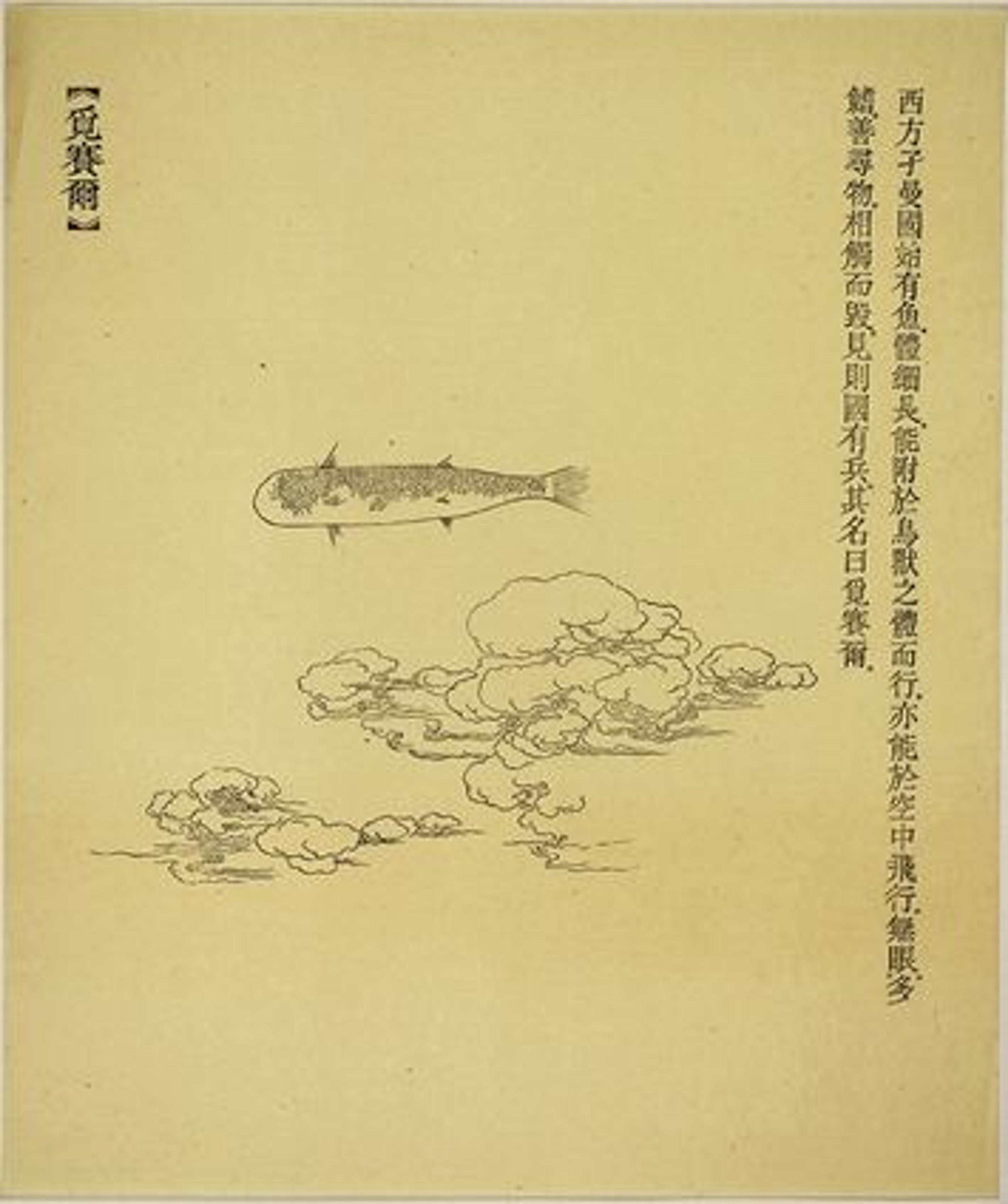

Left: Qiu Anxiong (Chinese, b. 1972). "Misaier" [Missile], in New Classic of Mountains and Seas I, 2008. Leaf from a portfolio of 12 woodblock prints, ink on paper, each leaf: 19 3/4 x 16 1/2 in. (50.2 x 41.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2013 (2013.944a–l)

Another picture also presents a sky scene, but this one bizarrely features a fish-like creature whose name, Misaier, is a close transliteration of "missile." The appended story reads:

The western kingdom of Jieman [Germany] was first to have this species of fish. It has a slim, elongated body. It can move around by attaching itself to birds and beasts. It can also fly in the air. Eyeless with multiple fins, it excels in seeking out targets and destroying them on contact. The sight of it heralds war. It is called "Misaier" [Missile].

Qiu's words for each image in the album convey the sense of wonder felt by someone from antiquity encountering the fruits of modernization. "They must appear like enigmatic monsters roaming the world," he remarks. Though a seemingly straightforward imitation of an antique model, his work wryly critiques the "unnatural" creations of our contemporary world.

The topics of the narrative texts appended to the generic images in Chinese painting are diverse, and the interaction of the two components—text and image—operates in innumerable ways to illuminate both the artwork and the artist. From Shitao's evocation of ancient masters to Qiu Anxiong's time-travel allegories, the works in Show and Tell demonstrate the expressive potential and lasting relevance of this type of pictorial storytelling.

Related Links

Show and Tell: Stories in Chinese Painting, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through August 6, 2017

Now at The Met: "Show and Tell: Exploring Storytelling in Chinese Painting" (January 31, 2017)

Articles Related to this Exhibition

Liu, Shi-yee. "'Show and Tell': The Art of Storytelling in Chinese Painting." Orientations 47, no. 8 (November/December 2016): 44–53.

Liu, Shi-yee. "Containing the West in the Manchu Realm? Emperor Qianlong's Deer Antler Scrolls." Orientations 46, no. 6 (September 2015): 2–13.

Liu, Shi-yee. "Emperor Qianlong's East Turkestan Campaign Pictures: The Catalytic Role of the Documentation of Louis XIV's Conquests." Arts of Asia, March–April 2017, 82–97.