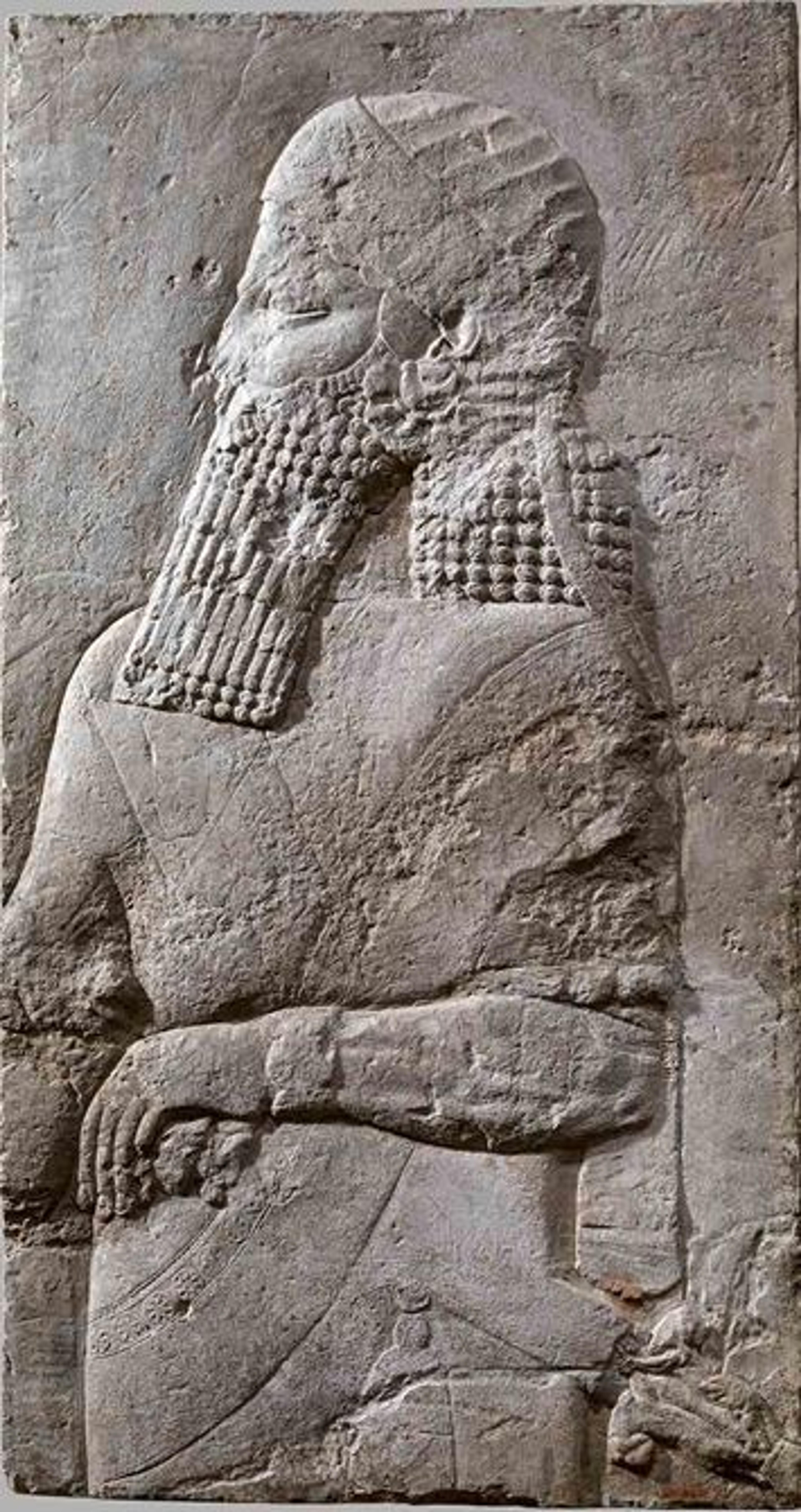

Assyrian crown-prince (detail), ca. 704–681 B.C. Mesopotamia, Nineveh. Neo-Assyrian. Gypsum alabaster, 26 1/8 x 14 x 1 1/8 in. (66.5 x 35.5 x 2.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932 (32.143.13)

«Excitement, curiosity, and the fear of an irresistible impulse to look directly at the sun were all common responses to this month's total solar eclipse. But for those familiar with the world of ancient Iraq, another association comes immediately to mind: the ritual of the substitute king.»

The story of the substitute king and his queen is a tragedy driven by fear, awe of the gods, and the uniquely important status of the (real) king. It begins with the achievements of ancient astronomers and priests, whose observations of the sky and of the phenomena of the earth formed the basis for one of the most important areas of knowledge in ancient Mesopotamia, that of divination. Through divination, priests could read the signs given by the gods in the heavens and on the earth in the form of omens. Using this knowledge, they developed a sophisticated system over thousands of years of observation and scholarship dedicated to predicting the future. If a prediction was especially dire, priests could conduct specific rituals to help mitigate or cancel the disastrous event portended in the omens, by appeasing the gods or directing their destructive force to another target.

One of the most serious omens was a solar eclipse, which predicted grave danger for the ruler of the area of the world in which it appeared. Ancient Mesopotamian astronomers had developed the knowledge to accurately predict eclipses with a high degree of precision. Once an eclipse was predicted and the area in which it would appear had been identified, the court and the priests took action. If the eclipse took place over Assyria, for instance, the Assyrian king would be in danger, and for the king to be in danger put the entire power structure of the kingdom at risk. So a substitute would be put in his place—literally, a substitute king, or šar pûhi (shar PU-khee) in Akkadian, the language of the Assyrian court and its official documents.

The substitute king did not have to look like the real king, but had to be a man. After he was selected, he was dressed in the king's garment, declared to be the king, and made to participate in other rituals investing him with royal identity. He was also given a young woman as a queen. After this, the true king withdrew from public view until danger had passed. The substitute king and queen were offered as sacrifices for the evil fate that was destined for the true king, taking it on themselves while he remained safely hidden. Like the moment of the eclipse, when both moon and sun are visible in the same place, the substitute king and the true king coexisted only briefly. Once the dangerous time had passed, the substitute king and queen were killed, the true king re-emerged, and the ritual was complete.

Although it seems like an especially gruesome fairy tale, there are many historical records of substitute kings and the real kings they protected from the anger of the gods. Erra-imitti, king of the city-state of Isin in southern Iraq from 1868 to 1861 B.C., died "after having sipped a broth that was too hot" while his substitute was still alive. So the substitute king, a gardener named Enlil-bani, continued to rule Isin until 1837 B.C.

Assyrian crown-prince, ca. 704–681 B.C. Mesopotamia, Nineveh. Neo-Assyrian. Gypsum alabaster, 26 1/8 x 14 x 1 1/8 in. (66.5 x 35.5 x 2.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932 (32.143.13)

Most substitute kings were not so lucky. A young man named Damqi was killed with his queen in the reign of Esarhaddon (680–669 B.C.) to protect the Assyrian crown prince Shamash-shum-ukin, who at that time was the ruler of the Babylonian territories of the Assyrian empire. Young Damqi was a member of the native Babylonian elite, the son of the chief administrator of the temples of the great holy city of Babylon. It seems that even powerful people could be forced into the substitute king role—in this case, Damqi may have been selected to terrorize the Babylonians, who repeatedly resisted Assyrian rule.

Eventually, the Babylonians and other enemies of Assyria got their revenge for centuries of Assyrian aggression by joining together to destroy the empire in 612 B.C. When their victorious armies sacked the Assyrian palaces, they chipped out the faces of many of the royal figures depicted in stone relief on the palace walls. One of the figures whose portrait was erased appears on this relief from Nineveh, now in the Museum's collection. His diadem and other aspects of his dress and attributes indicate that he was probably a crown prince, perhaps one of those who traded a substitute king and queen's lives for his own.

For further reading on the substitute king ritual, see Jean Bottéro, "The Substitute King and His Fate," in Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, trans. Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 138–155