Curator Conversation: Exploring Contemporary Aboriginal Art with Maia Nuku

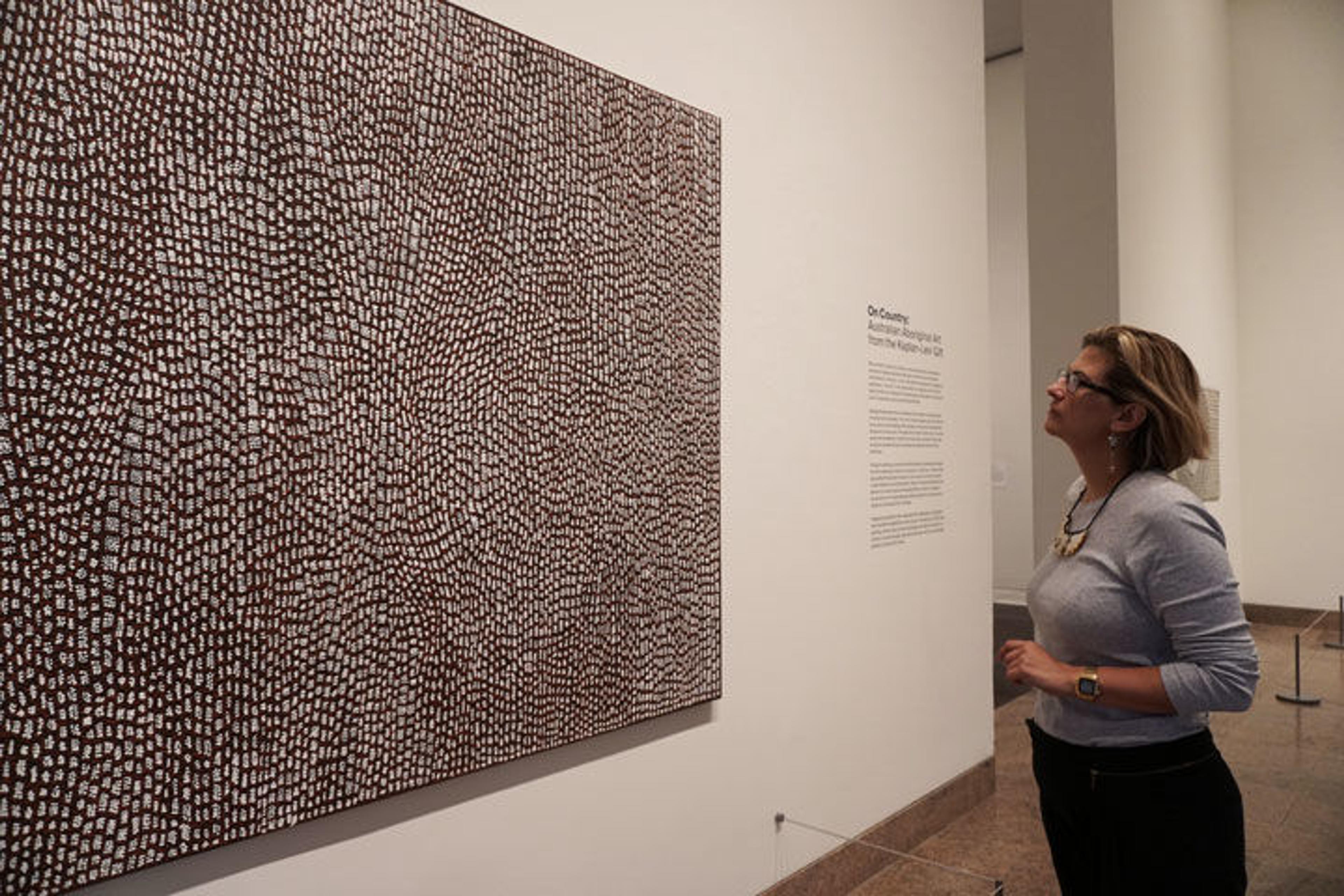

Associate Curator Maia Nuku in gallery 918

«Nestled in a quiet area of the Modern and Contemporary galleries overlooking Central Park, steps away from the crowds taking in Rodin at The Met, is a meditative installation of six works of contemporary art by leading Australian Aboriginal artists. On view through December 17, 2017, On Country: Australian Aboriginal Art from the Kaplan-Levi Gift marks an electrifying addition to The Met's holdings of contemporary art—a gift of six monumental paintings in which masterful indigenous artists explore aspects of nature and the elements, and their fluid relationship to time and ancestral landscape.

I recently took a tour of the exhibition with its curator, Maia Nuku—Evelyn A.J. Hall and John A. Friede Associate Curator in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas—to learn more about these works and the centuries-old art-making tradition they represent.»

Michael Cirigliano: This exhibition marks a transformative moment for the Museum. What impact do these six paintings by contemporary Aboriginal artists have on The Met collection?

Maia Nuku: This is a really exciting moment in the history of the Museum, in the sense that, for the first time, contemporary indigenous works from Australia are showcased in Modern and Contemporary's galleries adjacent to the great masters of the Western canon—well-known European and American artists of international renown. So we have the opportunity to really expand that canon to incorporate lesser-known, often-eclipsed artists who also operate on an international framework, whose works have, as well as a formal aesthetic, another aspect to them. Featuring these paintings in these galleries really allows us to see the work in a more global sense—not simply consigned to historical or ethnographic contexts as artifacts.

There have been exhibitions of contemporary Australian Aboriginal art in the Museum before; a selection of works were temporarily displayed downstairs in a space on their own, but they weren't in dialogue with other works in the collection. This time around it's really the adjacency that the paintings enjoy alongside the work of other great contemporary artists, masters of the acknowledged canon, that is so exciting.

Michael Cirigliano: This is exactly what The Met can do with a collection like this: give visitors the opportunity to see these contemporary works through that lens of history. Your department's galleries are just one floor below this, so it's a very nice juxtaposition.

Maia Nuku: Yes we do have an opportunity at The Met to really explore these kinds of visual dialogues. I often imagine the Museum as if it were a giant kaleidoscope of art, and these works present a new set of global coordinates that shift and alter that kaleidoscope. The paintings come into the fore and align in a different configuration; we can play with that dynamic in this Museum.

Michael Cirigliano: You note in the exhibition's wall text that Aboriginal artists see the act of painting as a "way of creating a visual archive of ceremonial knowledge," through song, dance, and storytelling. What exactly is the tradition that is being shown here, and what is the ritual involved in the creation of paintings such as these?

Maia Nuku: These artists are entitled to depict specific narratives pertaining to their relationship to "Country"—that is, to a particular tract of land, or water, or perhaps a story of a primordial being that may be related to the landscape that they're from. Not everyone can paint a particular story. It might be passed directly down from within your own family or it could belong to the clan that you've married into. So one very important and rather unique aspect of these paintings that's perhaps not that obvious to visitors is that there is an implicit genealogy in the relationship of these works to each other, something that is expressed through the interconnection of the stories that have been shared and passed down.

What I've aimed to do with the labels is really to acknowledge this genealogy by stating who has passed each particular story to the artist. One artist, Abie Loy Kemarre, was entrusted with the custodial rights to depict the narrative relating to the bush hen by her grandfather; another, Doreen Reid Nakamarra married into a clan and in time was allowed to depict a narrative relating to a particular site of her husband's people. The manner in which these stories are passed down is very conscious and deliberate; it's not random at all but targeted. You find this with many cultures who do not use text—the breadth of their knowledge is committed by means of oral traditions and visual histories, entrusted in individuals who will ensure they are passed on.

The act of painting them is not a solitary endeavor usually; you have the artist painting the canvas, which is laid flat on the ground, but then the younger generations might be there telling them the story. So the paintings act as a mnemonic for the passing of these stories, because what you're doing in the creation of paintings is saying the story, singing the songs, remembering the oral narrative and that history.

It's not unusual for people to be working away when someone might break into song or tell a story or recall a humorous anecdote. It's a very specific way of making art. In one respect, you could even say that the final outcome of the process, the artwork that manifests is almost incidental. I'm being deliberately provocative, but it's true to a degree—it's in the making of the work that you harness the moment and capture space and time. The physical act of coming together as a community on the land to bring the work into being is what's important.

Michael Cirigliano: Would any of the stories be determined before the act of painting begins, or does the artist come to the canvas and then the stories unfold?

Maia Nuku: Great question. Yes, they pretty much know the story before they set out to paint. The narrative is like the template; it is in the interpretation of that narrative that the individual artist has a chance to excel. It's something that I've been thinking about a lot as I've been taking people around the exhibition. In a way, a tremendous amount of creativity is unleashed due to the constraints of each artist and their being limited in terms of the narrative they can paint, the stories they can tell.

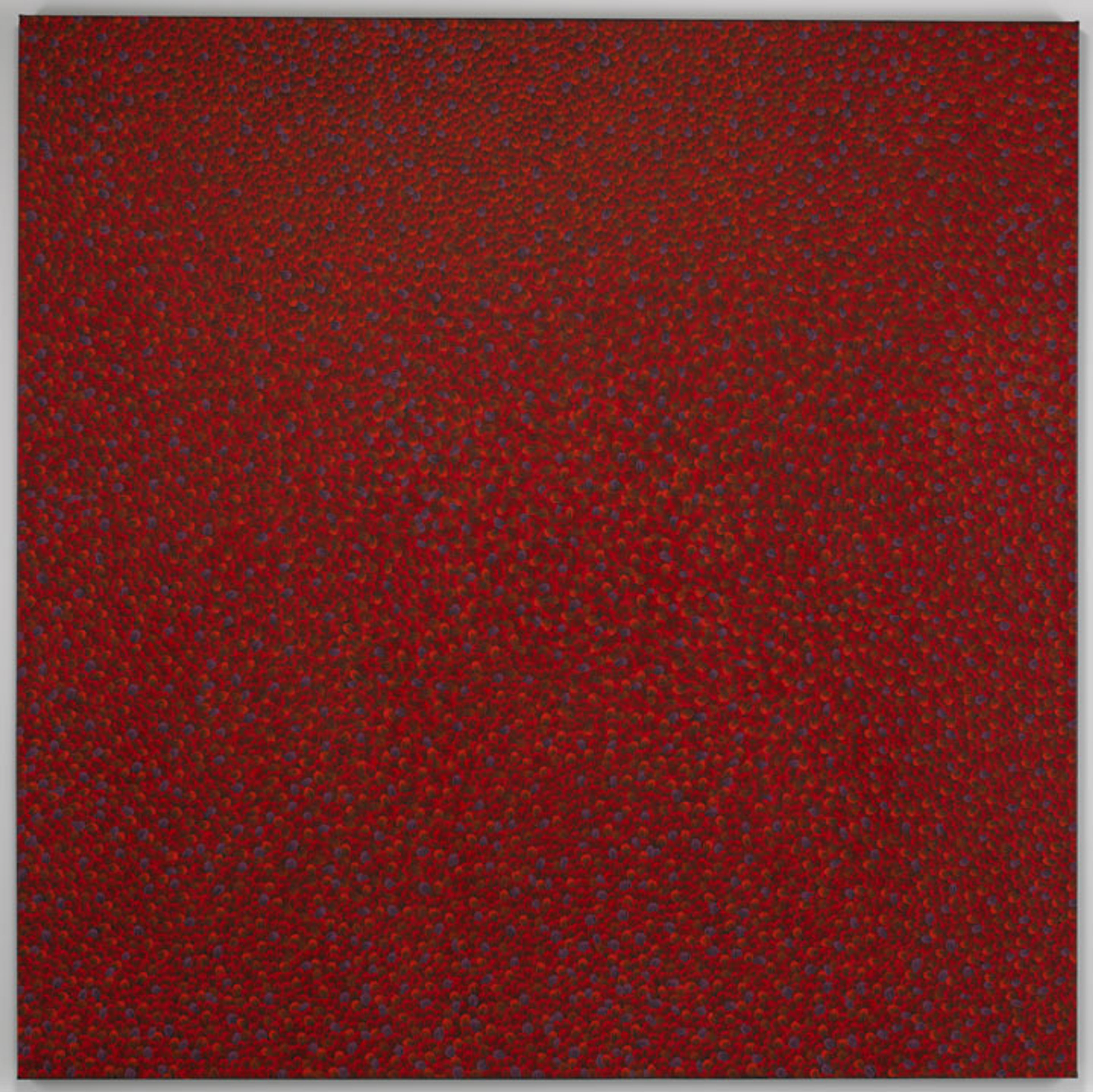

If you take Abie Loy Kemarre for example, she is entitled to paint a singular narrative in Bush Hen Dreaming – Bush Leaves. By working within the tight framework of that narrative she really explores the myriad ways that she can really expand that story. How might she innovate in terms of rhythm, color, and technique? She begins with this motif of a seed, of a bush leaf, and really explodes the idea out. What's so extraordinary about these paintings is the way in which they can operate in several realms simultaneously: at one level you can take the microcosm of a single seed or leaf, a bush hen's feather; and then, when you take a step back, it's expanded to take up the entire universe.

Abie Loy Kemarre (Australian, born ca. 1972). Bush Hen Dreaming – Bush Leaves, 2003. Acrylic on canvas, 71 5/8 x 71 5/8 in. (182 x 182 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi, 2017 (2017.251.1). © Abie Loy Kemarre. Photo by Spike Mafford © 2014

You can look at Bush Hen Dreaming and focus on the fact that each of those strokes are the individual feathers of a bush hen caught in a dizzying frenzy as she searches for bush leaves and seeds in the surrounding landscape. From there you can expand that single element to appreciate that the artist is in fact making reference to the entire repertoire of customary knowledge invested in the women that pertains to bush medicine and understanding the species of bush plants and shrubs that will help you survive the harsh seasons and ongoing environmental cycles that take place over many decades and centuries. So in focusing on a single coordinate—a feather, a seed—Kemarre is actually able to penetrate something vital and much more universal.

Michael Cirigliano: So the painting can be viewed at the level of the artist and her formal technique, and then on top of that there's the level of what it can depict literally, and then there's an additional meta layer that relates to what the story and the artistic representation mean specifically to her culture and to how that is identified within her community?

Maia Nuku: Yep, you've got it. Bang on!

Michael Cirigliano: Are there any occasions where these artists work outside of that tradition or that narrative, or is it really implicit in their artistic tradition to always be communicating these types of stories related to "Country"?

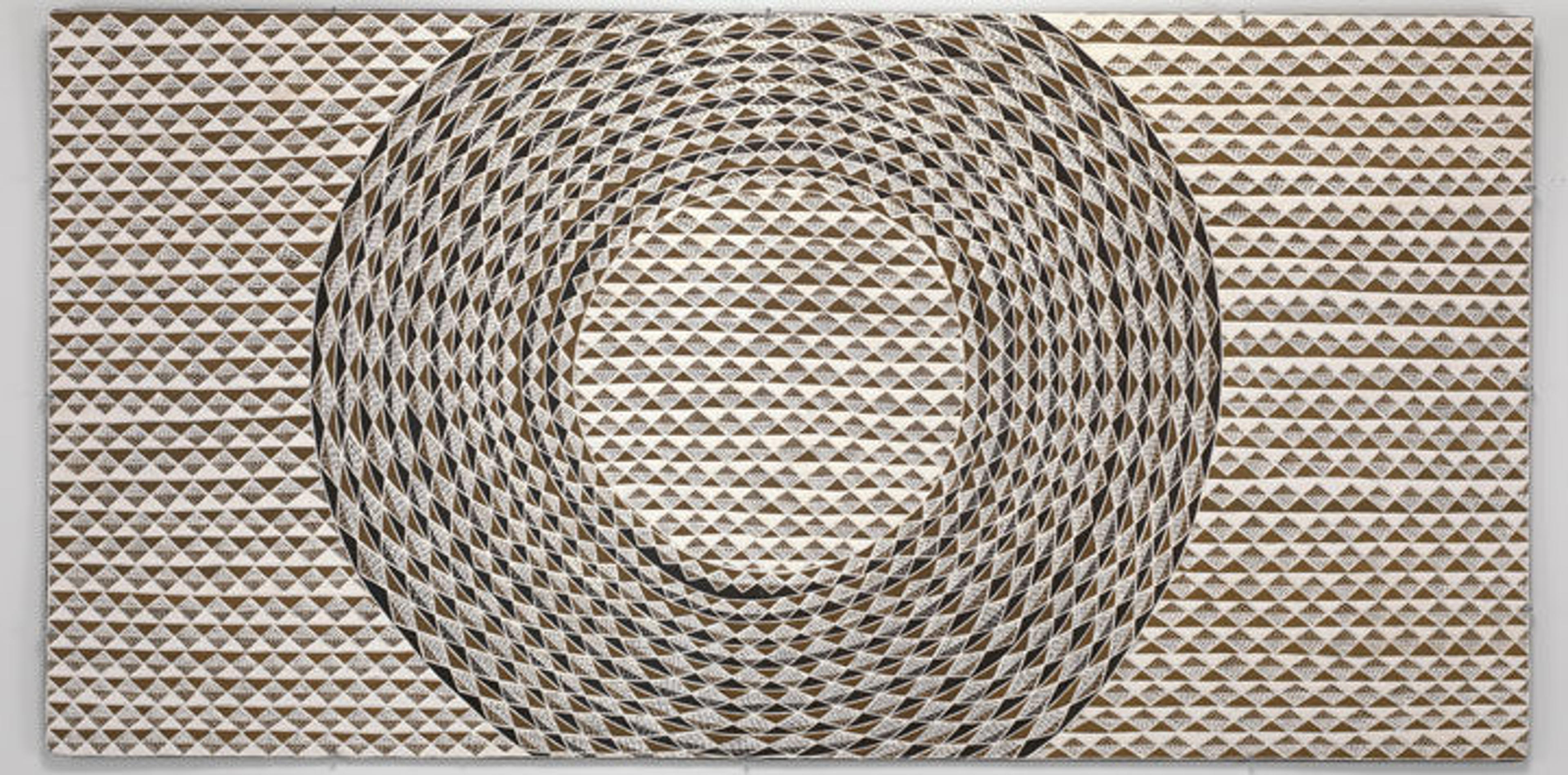

Maia Nuku: I would say that Gunybi Ganambarr is slightly different. He's a younger artist who has exhibited in the Asia-Pacific Triennial, and is very engaged with the international art scene. In Buyku, he's talking about ancestral waters that relate to his mother's land, but I see him as slightly different from the others. Visually, you can see the work looks slightly different—not just the design, he's thought about what he's going to paint on, salvaging scrap metal, rubber, industrial laminate board. He's playing with scale, working with big rolls of steel that he cuts into; or picking up strips of rubber from used tires found on construction sites in that area.

Gunybi Ganambarr (Australian, born 1973). Buyku, 2011. Ocher on incised laminate board, 35 7/8 x 71 1/4 in. (91 x 181 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi, 2016 (2016.717.1). © Gunybi Ganambarr. Photo by Spike Mafford © 2014

Michael Cirigliano: His is the only work that's not painted on organic canvas material. It's on industrial laminate. Is there a statement he's making even in that choice of materials?

Maia Nuku: Definitely. He's moving the debate forward and innovating. Interesting that he's the one that would choose industrial material as his medium, because in the past it was customary to paint on eucalyptus bark in this area of northeastern Australia, Arnhem Land. So he's taken the customary position and flipped it on its head. He doesn't want to just paint on canvas, he's using local resources available to him; it's just that these now include the debris of industrial sites in the region. This gives him an opportunity to draw out other crucial narratives that are so pertinent to people in the region—dispossession, the continued alienation of Aboriginal peoples from their customary lands. He's really using the medium itself to think through the global narratives that he and his people are invested in.

Michael Cirigliano: And what are the mechanisms that a visitor can use to read the storytelling aspects of these paintings?

Maia Nuku: Well, it's tricky! These paintings are really accessible on one level because of their formal qualities, and people talk a lot about abstraction, expressionism, the gestural quality of the work, and obviously these intrepretations do allow for one vein of of understanding the work. What we've tried to do in the exhibition is to acknowledge the formal aesthetics of the paintings but at the same time contextualize them in terms of story, and how—and even why—they are made.

There are different ambitions embedded within the art I look after from Oceania. On one level the art is about what things look like, but with indigenous art we want to help people also understand the agency of these things. What is it that the art is doing? What kinds of effects do the works generate? They're optically fertile and dynamic, so I think people are drawn to them. But then I think we have to help the visitor a bit further into a fuller understanding of the artwork itself.

Michael Cirigliano: They're so well executed that they can be enjoyed purely on that level of abstraction.

Maia Nuku: Yeah, I think that's why people respond to them so strongly. They're meticulously executed and very dynamic, so people look very closely and are then really fascinated to know what they mean. I get that a lot with the works of art I look after in the Oceanic galleries. People are taken with the majesty, the scale, the awesome power of the art, but then it can be difficult for visitors to penetrate a more conceptual notion of what things were used for, and why they look like they do. There are key principles of Oceanic art that I think can really help people get close to an understanding: it's about ancestry and relationships, how art can help people cross thresholds into different realms, from past to present and on into the future, between life and death for example. These are themes that come up repeatedly for both historical and contemporary works in the Pacific. In terms of thinking about how we can present art from this region of the world here at The Met, I think it's productive and exciting to try and build out from these core concepts, because this is how Pacific peoples understand them.

Michael Cirigliano: Of course this question would come from an editor, but tell me about the idea of "Country" with a capital "C." How should one read into that?

Maia Nuku: [laughs] That's really great! Yes, we were careful to acknowledge the notion of "Country" with a capital! It's a term with distinct resonance for indigenous Australians. It's appropriate to capitalize because we are referring to it in pronoun, that the land is personified. It is an animated landscape where the resonance of primordial beings continues to be felt; ever present, one can tap into it to feel enlivened. If you travel to Australia and are invited onto Country, you'll travel with the tribal leaders and they'll take you to a site, but they'll always go out first and call out to their ancestors to say who you are. It's a kind of customary clearance—and that's it, you are literally clearing customs but in a spiritual sense! It's incredible, you cross into this space where your hosts are singing or calling out, announcing your arrival with them—in this way they will welcome you onto the land, into ancestral time. That's really the point of Country, it's a personification of an idea; these are not empty concepts, but actual realities.

Michael Cirigliano: Now tell me about the three 19th-century artifacts that are here in the gallery, two from The Met's Oceanic holdings and one from a private collection. How do these amplify the narrative of the paintings?

Maia Nuku: I thought it was important to connect the historical collections of my department with the contemporary paintings of Modern and Contemporary. We have these spectacular incised pearl-shell works in The Met collection, one of which still retains its hair-string belt. I thought these were a perfect way to really speak to the long trajectory of this art-making tradition and demonstrate how Aboriginal peoples have always sought to capture narrative in a very tangible, concrete way.

These shells were traded across vast swathes of territory in Australia and came to be collected in the 18th and 19th centuries in vastly distant territories. They were extremely rare and valuable. You can imagine that in a world where things are ephemeral—you make art using bark, you adorn yourself in paint, charcoal, and ochre—there's not a lot apart from rock and stone that's of great permanence. So when you find a big, bright, shiny and lasting material like pearl shell, it is inordinately valuable. Its translucent, shimmering qualities were likened to the elemental forces of lightning, these ephemeral forces somehow captured within. Held or worn as a breastplate, they were used in ceremony, including the initiation rites for young men, when the designs on them were interpreted. Again they were a means to pass along community stories and as a dynamic means to transact with ancestors—to heal a relative, to ask for rain.

Michael Cirigliano: And I love the parallel of these working on the level of abstract art, too. They're very geometric, linear, but like you said, the more that you look at them, the more you see a sequence of pictorial and abstract dimensions.

Maia Nuku: And of course the hair is another important element here, which is really a concrete reference to genealogy. It's really quite something to take your own hair and weave the strands into threads that you can bind up and roll into a hair-string belt that can be passed down through your family for generations. The materiality of hair is a very significant, sacred thing.

Michael Cirigliano: And the permanence of it. The hair will last a lot longer than anything organic, really.

Maia Nuku: Anything that comes from the body is seen as incredibly powerful.

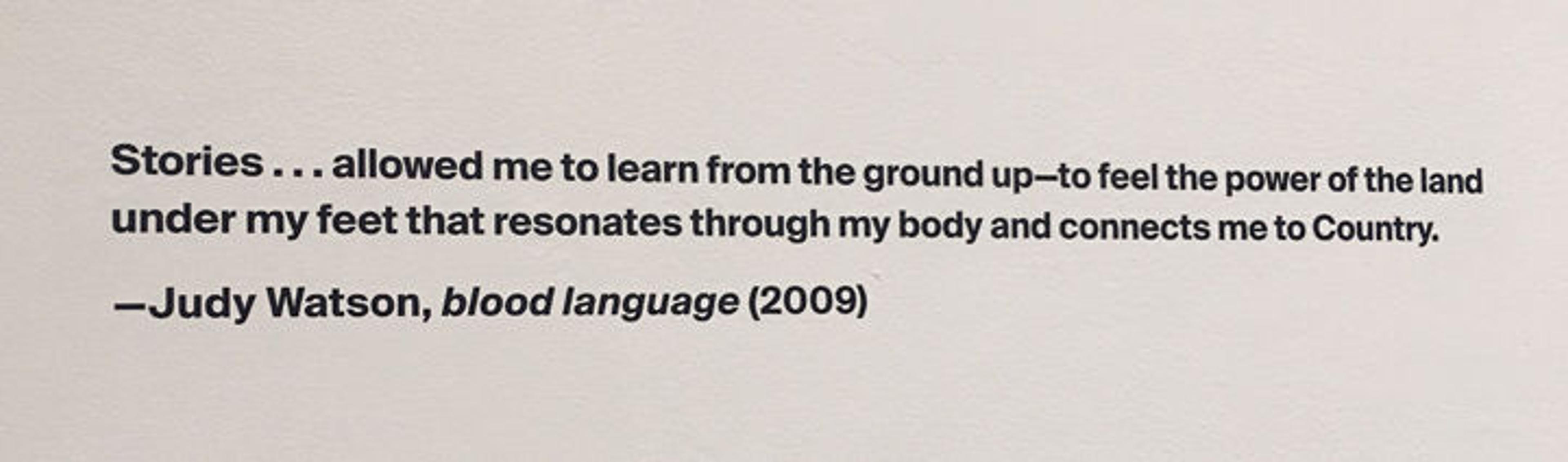

Michael Cirigliano: One more question for you: Tell me about the Judy Watson quote that's silkscreened on the wall.

Maia Nuku: I really wanted to include this quote because Judy Watson is a contemporary artist who works a lot with institutions that house ancestral treasures from Australia. She thinks a lot about the role of those works in institutions, their trajectory to these places, and she's traveled the world to look at and research such collections. She herself has described her work as wanting to unearth the hidden histories of indigenous experience, in her own words: "to rattle the bones of the museum," which I think is a fantastic quote. I wanted to include an artist who is interested in the shifting regimes of value as they moved in and through different contexts—from paintings made within community, now transiting into art galleries and the international market.

Watson's art practice is very diverse and she's interested in thinking about the complications of history, and the troubled and violent history of Australia as it relates to Aboriginal peoples and the alienation of their land. I thought it was appropriate to have a text that captures the idea of this highly problematic relationship with land given that we were grounding ourself in "Country." So we move from one relationship with land—one of celebration, as depicted in the paintings—to one that is mindful of the insult and injury that has been a reality of colonization in the territory.

Michael Cirigliano: It's a really gripping declaration, and after speaking about this with you, I'm seeing different levels of importance to certain words: obviously Country with a capital "C," but also "resonating through my body"—that idea of the body in terms of connection and lineage. It's really these artists connecting with their own art in a way that is so much more interwoven than the general contemporary sense of making a work of art, selling it . . .

Maia Nuku: Exactly, and what's coming to me as you're talking is the fact that each of these artists sees themselves as a present-day vehicle for this knowledge; each is mindful that we are simply custodians of knowledge for this generation. It's our duty and obligation to pass that knowledge down; each of us is grappling with these obligations and challenges.

Michael Cirigliano: In that perspective, this is where curation moves away from the modern, clichéd definition of just choosing what is hung on a wall, and back to the original definition of caring for a collection of art. If we're in a position at an institution like The Met to care for these works and to provide access to them for future generations, that's really what curation is about.

Maia Nuku: Absolutely. When I called her to ask if I could use her quote, she was very positive, delighted that her quote would be included not only in the company of these great artists, but I guess also because this has been a highly anticipated moment for many people inside and outside Australia, that an institution like The Met, in a city like New York—such an energetic hub of contemporary international art—would acknowledge the work of Australian Aboriginal artists in the grand schema of art.

It feels like—after the models of globalization and capitalism, which appear to be wearing themselves out—people are looking for other modes, searching for alternative ways to operate, artistically and in general. I think indigenous epistemologies can really help. These paintings give us the opportunity to think about our inter-connectedness, our relationship with time, with our ancestors, and with the land. Simple truths perhaps, but they've never seemed more pertinent. Curating in this sense is certainly in taking care of and attending to; it's an obligation, but definitely a happy one! [laughs] It's incredibly exciting that we can expand people's definition of what art is.

Editor's notes: This interview has been condensed and edited from its original form.

This article was updated on July 24, 2019, to correct a spelling error.

Related Link

On Country: Australian Aboriginal Art from the Kaplan-Levi Gift, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through December 17, 2017

Michael Cirigliano

Michael Cirigliano II is the managing editor in the Digital Department.