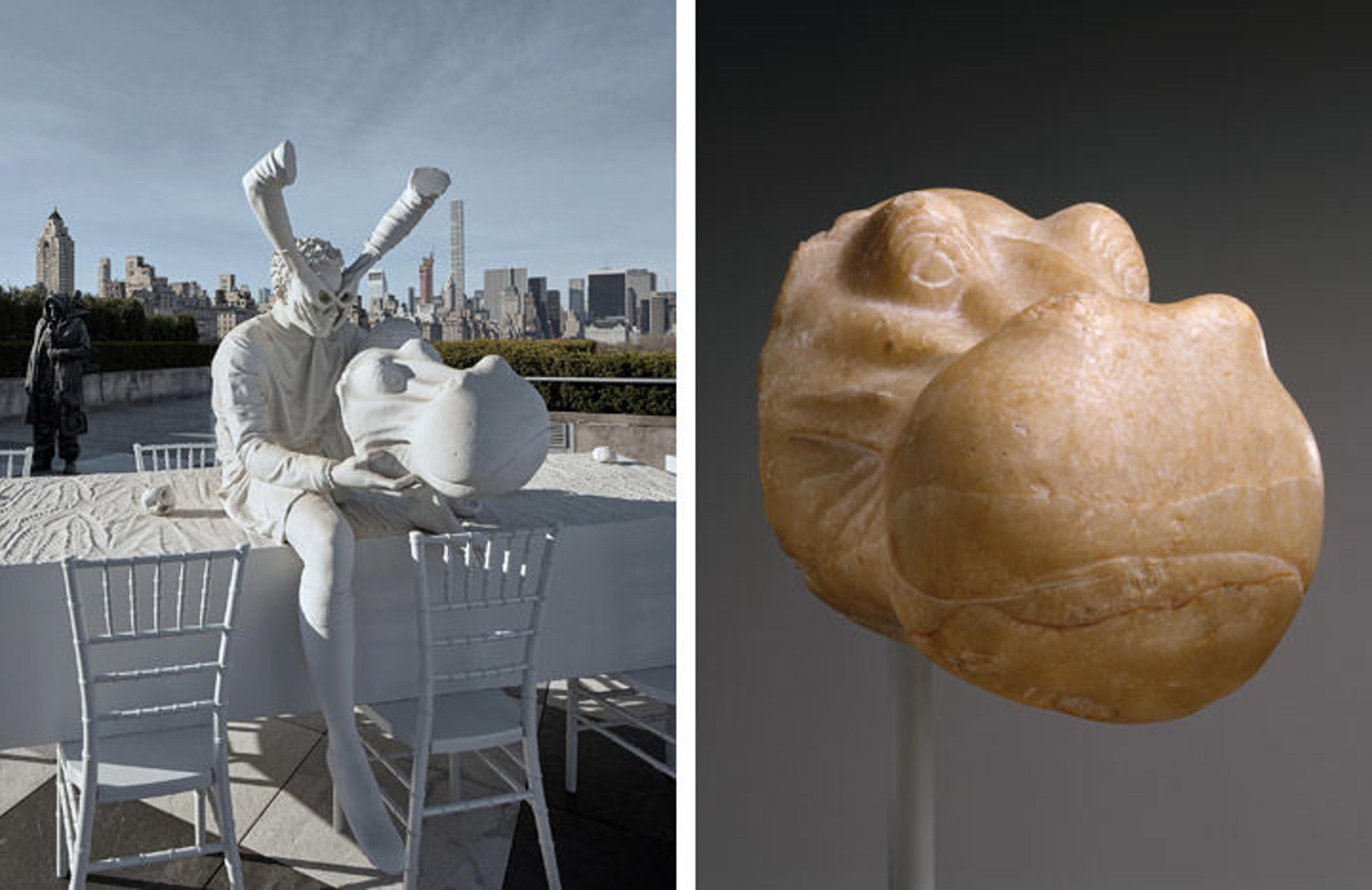

View of Adrián Villar Rojas's The Theater of Disappearance on The Met's Cantor Roof Garden. All installation photos by Jörg Baumann and presented courtesy of the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery; and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City, except where noted

«Depending on how you look at it, Adrián Villar Rojas's The Theater of Disappearance—The Met's 2017 Roof Garden Commission—may, at first glance, seem like a surreal dreamscape, decked out with the decadent vestiges of a crazy party. Some of the sculptures are passed out on tables littered with broken wine glasses and plates, while others are found canoodling underneath other statues, or kissing near the terrace. If you linger on the rooftop at dusk, when the fog wraps around the skyscrapers, the sculptures begin to appear like a conjuration of ghosts haunting the Museum and watching over the city.»

The installation is full of duplicity: it is both academic and whimsical, disruptive and atmospheric. Rojas refers to it as a Museum-wide scavenger hunt, one that boasts more than 100 replicated pieces handpicked from an array of sculpture representing several of The Met's curatorial departments. The replicas were either milled or 3D printed, and are made in urethane foam coated with matte industrial paint.

You don't need to be an expert in art history to appreciate the mysticism that The Theater of Disappearance creates on the roof; it's accessible regardless of any background knowledge. And like any good dinner party, the guests on view here feast on course after course of inside jokes. I've highlighted below the origins of a few of the replicas, so you won't have to feel FOMO once you get to the party.

While dwelling on the mysterious sculpture of a man with a pair of hands suspended in the air before him like binoculars, you might miss the tomb effigy of Elizabeth Boott Duveneck (shown in the foreground above), which her husband created in her honor after her death in the late 1880s. She lies in a riot of various objects, including one particularly conspicuous otter, which you might recall from gallery 134 in the Department of Egyptian Art. In Ptolemaic times, otters were associated with the goddess of Lower Egypt Wadjet, and this otter's very particular pose, with raised paws, signifies its adoration for the sun God. On one corner of Duveneck's tomb is a precariously placed vase; Spanish and Italian aristocracy used to eat the clay of this vase in order to make their skin appear paler.

Top: Frank Duveneck (American, 1848–1919). Tomb effigy of Elizabeth Boott Duveneck, 1891; cast 1927. Bronze and gold leaf, 28 1/2 x 85 x 41 1/4 in. (72.4 x 215.9 x 104.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1927 (27.64). Bottom left: Otter statue. Late Period or Ptolemaic Period (664–30 B.C.). From Egypt. Cupreous metal, H. 45.5 cm (17 15/16 in.); W. 8.3 cm (3 1/4 in.); D. 12.4 cm (4 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lily S. Place, 1923 (23.6.2). Bottom right: Covered jar, ca. 1675–1700. Mexican. Earthenware, burnished, with white paint and silver leaf, H. 27 15/16 in. (71 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2015 (2015.45.1a, b)

An armed French knight, plucked right out of The Met Cloisters, lies on the table adjacent to the tomb. The original medieval sculpture features a Chinese sword that strangely does not match the rest of his European armor and weaponry. The figure snuggling up to the knight is none other than the exhibition's curator, Beatrice Galilee, who is seen high-fiving him, her hands nearly scraping the Persian plates from A.D. 399–420 found in gallery 405.

Top: View of The Theater of Disappearance. Bottom: A knight of the d'Aluye family, after 1248–by 1267. French. Limestone, 13 x 33 1/2 x 83 1/2 in., 1,197 lb. (33 x 85.1 x 212.1 cm, 543 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.201)

As you pass through the banquet tables, it might be hard to recognize the sleeping youth who is laying across the famous jasper face of a queen. The fragment was traced back to the New Kingdom, when Egypt was ruled by King Akhenaten, whose interest in solar religion led to innovation in Egyptian arts.

Left: View of The Theater of Disappearance. Right: Fragment of a queen's face. New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten (ca. 1353–1336 B.C.). From Egypt; probably from Middle Egypt, Amarna (Akhetaten). Yellow jasper, H. 13 cm (5 1/8 in); W. 12.5 cm (4 15/16 in); D. 12.5 cm (4 15/16 in). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926 (26.7.1396)

In a mise-en-scène that seems to mimic the folkloric tale of a stork that delivers babies, a swaddled baby lies on a table next to a large bird that watches over it. The bird was originally made by the Senufo people in the Ivory Coast at some point in the 19th to mid-20th century.

Left: View of The Theater of Disappearance. Photo by the author. Right: Bird (Sejen), 19th–mid-20th century. Côte d'Ivoire. Senufo peoples. Wood, iron, twine, H. 55 11/16 x W. 24 1/4 x D. 15 in. (141.5 x 61.6 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.165)

Rojas said that he aimed to destabilize the hierarchy of museums, an intent that is evident in the way he presented the sculptures. An Asian woman in sneakers straddles the shoulders of an Egyptian king, her hands covering his face, and she raises the head of Tutankhamun above her like a war trophy. An African American male observes his surroundings, holding the head of a hippo in his hands that was originally used in Ancient Egyptian religious rituals. The models are contemporary figures immersed in and interacting with these ancient sculptures, perhaps even dominating them.

Left: View of The Theater of Disappearance. Right: Head of a hippopotamus. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Amenhotep III (ca. 1390–1352 B.C.). From Egypt. Travertine (Egyptian alabaster) with traces of gesso and red pigment, H. 14 cm (5 1/2 in.); W. 12.2 cm (4 13/16 in.); D. from back to jaw 15.2 cm (6 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, Gift of Henry Walters, by exchange, Ludlow Bull Fund, Beatrice Cooper Gift, and funds from various donors, 1997 (1997.375)

The Theater of Disappearance creates a rupture that points to the fact that history is edited, that it is moved and positioned and repositioned by human hands—in this case those of Rojas and Galilee. Rojas shows that these works are imbued with a narrative that was chosen by curators and art historians, and the chaos—this scrambled encyclopedia of art—attempts to release them from the standard narrative we assign to art history. The sculptures look like they're finally breathing.

Related Link

The Roof Garden Commission: Adrián Villar Rojas, The Theater of Disappearance, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through October 29, 2017