«Accompanying the exhibition at The Met Breuer, Marsden Hartley's Maine is the first publication of this scale to focus on Hartley's complex and shifting relationship to his native state. Illustrated with works from throughout the painter's career, the catalogue provides nuanced discussions of Hartley's artistic range—from the exhilarating Post-Impressionist landscapes of his early years to the late, roughly rendered paintings of Maine and its people.»

Left: Marsden Hartley's Maine by Donna M. Cassidy, Elizabeth Finch, and Randall Griffey features 194 full-color illustrations and is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

I had the opportunity to speak with Randall Griffey, one of the three lead authors of the book and the organizer of the exhibition at The Met Breuer, to discuss Hartley's ties to home and how he shaped his identity as an artist.

Rachel High: Hartley is perhaps best known for his painting Portrait of a German Officer, a mainstay of art history textbooks. How did you become interested in his lesser-known paintings of Maine?

Randall Griffey: I wrote my doctoral dissertation on Hartley's late paintings from the 1930s and 1940s, and I did that partly because I felt the work he did in Germany around and during World War I had been treated fairly and thoroughly while more remained to be said about other aspects of his career. The book and the exhibition don't only focus on the late Maine work; they also feature Hartley's earliest paintings of Maine's western hills from 1908–9. The fact that he was painting the state at this early point underscores just how important Maine was for his career overall.

The concept of the exhibition emerged from conversations with Elizabeth Finch at the Colby College Museum of Art and Donna Cassidy, a professor at the University of Southern Maine in Portland. Hartley has not had a large monographic museum exhibition in New York since 1980, and, of course, he is from Maine, so Colby was keen to show Hartley at home. Both the Colby and The Met collections have great strengths in Hartley, so it made sense for the two institutions to partner for the exhibition and catalogue.

Rachel High: I find your essay on Hartley's return to Maine fascinating because it contextualizes his promotion of himself as the painter of Maine as an intentional career move. Why did this status appeal to Hartley at the time?

Randall Griffey: That's one aspect of Hartley's career that might seem a little bit strange looking back from the 21st century. Hartley felt compelled to and ultimately did successfully promote himself as a great modern painter of Maine, but why would an artist ever so deliberately associate with one specific geographical region?

Hartley's late career coincided with the heyday of Regionalism in American art. This is the period that saw Thomas Hart Benton working in Missouri, Grant Wood in Iowa, and John Steuart Curry in Kansas. There was also an expectation of rootedness within the Stieglitz circle—from Alfred Stieglitz specifically—so pressure came at Hartley not only from the more conservative faction of Regionalism, but also from the American avant-garde.

For many years, Hartley resisted this pressure and expectation. In fact, it led to an irreconcilable rift with Stieglitz in 1937, when Stieglitz gave up and thought Hartley was never going to create great American art because he had insufficient roots in America. Their rift ultimately played a role in Hartley's subsequent artistic choices. So yes, his return to Maine was a conscious career move to a certain degree.

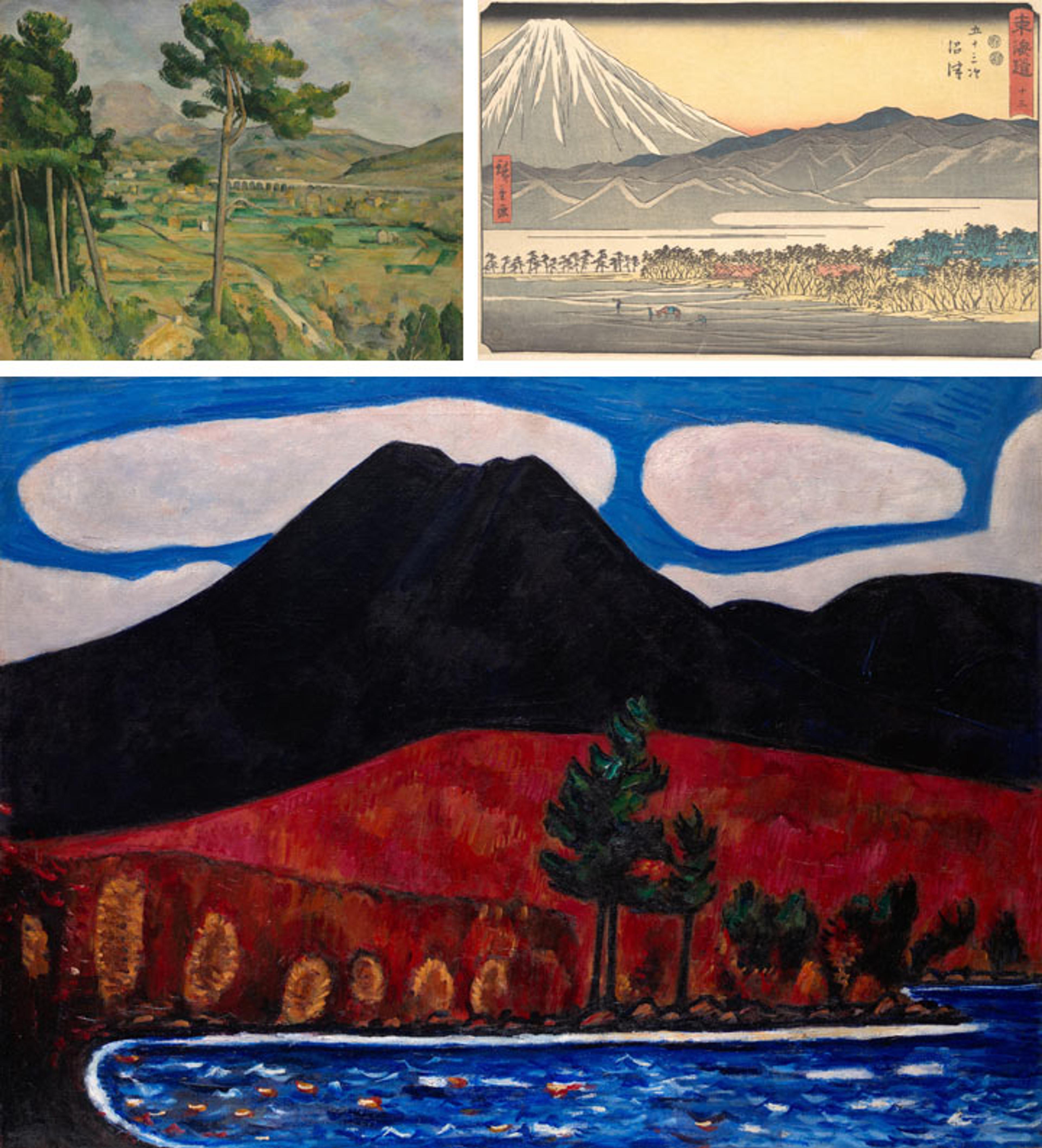

That said, Hartley wasn’t thinking exclusively about American art, and he interpreted Regionalism in multiple ways. In claiming Mount Katahdin as a signature subject, he was taking a page out of the book of Paul Cézanne, who is famous for his paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire in the South of France in the Frenchman's home of Aix-en-Provence. We think of Cézanne as a universal early modern master, but Hartley responded to him as a Regionalist. Cézanne gained his acclaim by an artistic devotion to his home, which is exactly what Hartley aspired to do.

In a way, you could also see the great Japanese printmakers Hokusai and Hiroshige as Regionalists, renowned for, among other things, their serial views of Mount Fuji. Hartley was thinking of Regionalism in a broad, international sense, and that affected how he presented himself to his audiences: he wanted to be known as a great American artist and saw that depicting his native state was the way to gain comparable fame as an American artist.

Top left: Paul Cézanne (French, 1839–1906). Mont Sainte-Victoire and the Viaduct of the Arc River Valley, 1882–85. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32 1/8 in. (65.4 x 81.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Top right: Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). Numazu, undated. Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper, 97/8 x 143/4 in. (21.5 x 37.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Henry L. Phillips Collection, Bequest of Henry L. Phillips, 1939. Bottom: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Mount Katahdin (Maine), Autumn No. 2, 1939–40. Oil on canvas, 30 1⁄4 x 40 1⁄4 in. (76.8 x 102.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith and Milton Lowenthal Collection, Bequest of Edith Abrahamson Lowenthal, 1991 (1992.24.3)

Rachel High: These connections among Hartley, Stieglitz, and Regionalism remind me of the chronology at the beginning of the book. It lists events in Hartley's life, Maine, the art world, and the world at large in one continuous timeline that contextualizes Hartley's experiences and decisions.

Randall Griffey: I'm glad you like the catalogue chronology. It includes, for example, the centennial of Cézanne's birth in 1939. It is no accident that Hartley finally made the trek to see Mount Katahdin that year. The mountain had also made headlines the summer before he went up, when a nine-year-old boy by the name of Donn Fendler from Rye, New York, went missing for several days. This saga made front-page news in the New York Times. Fendler became a kind of a viral celebrity at the time, so Hartley's art connected to both lived experience and current events. Coincidentally, Fendler died only recently, and the Times featured an extensive obituary that recounts his disappearance and the media coverage it garnered.

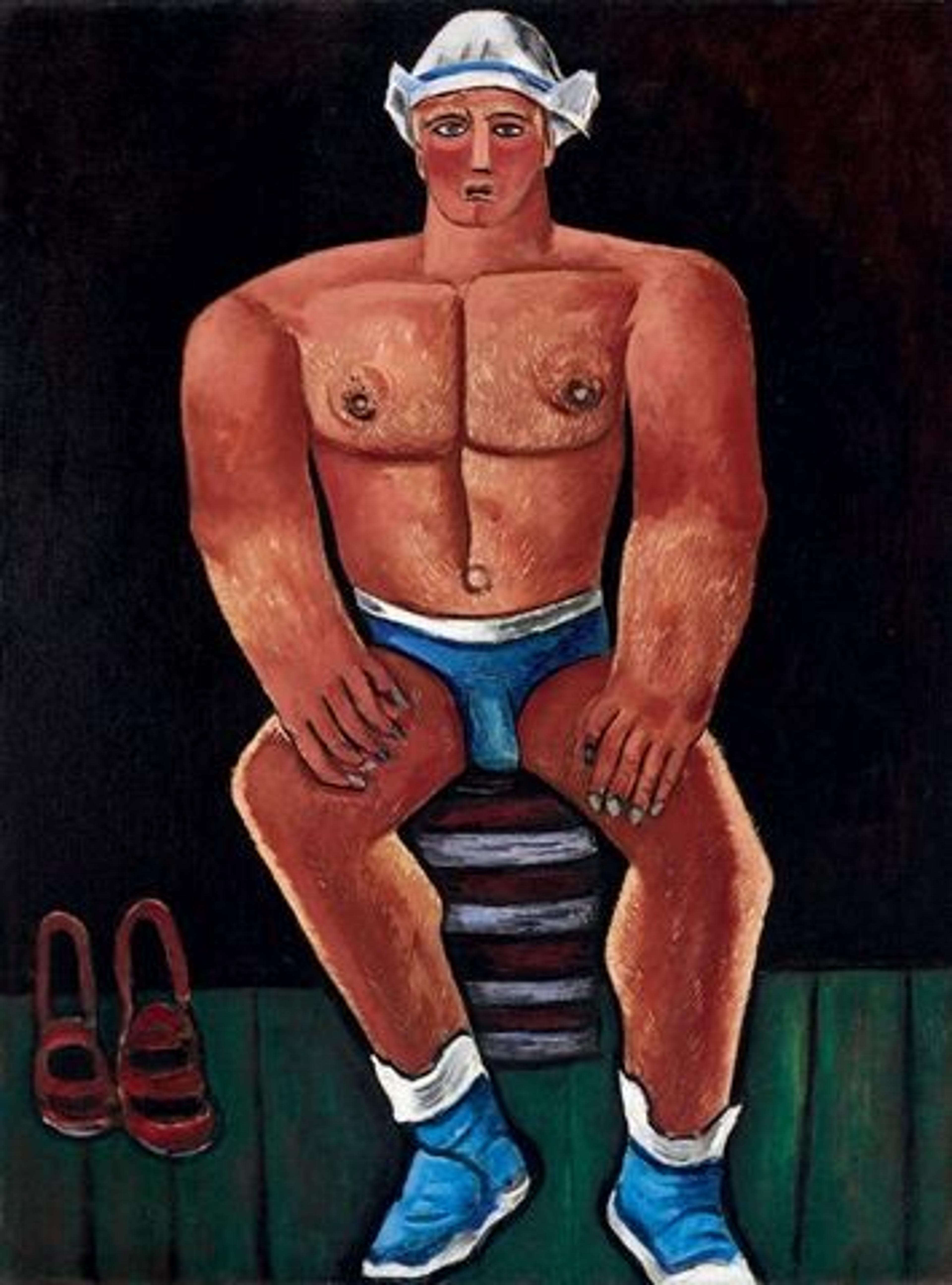

This connection to lived experience in Hartley's work is interesting and, in that vein, we made some progress figuring out a few of his male muses. One of the highlights and revelations for people in the show and book will be his figure paintings. Admittedly the works are not meant to be portraits, but the identity of Hartley's muse for Flaming American (Swim Champ) is published in the book for the first time. Even looking back from the 21st century, these paintings seem pretty audacious. This was not a private erotic art, however; he showed these works in public exhibitions right alongside his landscapes.

Left: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Flaming American (Swim Champ), 1939–40. Oil on canvas, 40 3/8 x 30 3/4 in. (102.6 x 78.1 cm). Baltimore Museum of Art, Purchase with exchange funds from the Edward Joseph Gallagher III Memorial Collection

Rachel High: You traveled to Maine while in the research phase of the publication and exhibition. In what ways did the landscape illuminate your understanding of Hartley's work?

Randall Griffey: I did walk a little bit in Hartley's footsteps, but I didn't recreate every step along the way. I went out to Corea, Maine, where he spent two stints living and working in the last years of his career. Corea is the setting for The Met's great Lobster Fishermen, which was the first of Hartley's works to enter The Met collection when it won an award in the Artists for Victory exhibition in 1942.

In Corea I sought out Hartley's studio, which was the second floor of a then-abandoned (though, interestingly, not now) Baptist church. The church was open and no one was around, so I decided to sneak upstairs. There was no clear evidence of Hartley's past presence there, but I did notice when looking out the window from the second floor that you have a view of Corea Harbor that is so close to what he paints in Lobster Fishermen, down to that strip of wooded island. This view helps to understand the painting's skewed perspective. Hartley is splicing two vantage points and, based on my visit to Corea, I think that second perspective is the view that he had from his studio space.

Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Lobster Fishermen, 1940–41. Oil on hardboard (Masonite), 29 3/4 x 40 7/8 in. (75.6 x 103.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1942 (42.160)

I didn't go as far north as Katahdin, but the show culminates with his paintings of the mountain, a design that is meant to be analogous to Hartley's own journey, both literally and figuratively. I hope the show and the book evoke the experience of leaving a place and then trying to come back, which is often fraught as it was with Hartley, and that viewers and readers will reflect on their own personal journeys as they follow and learn about Hartley's relationship with his homeland.

Related Links

Marsden Hartley's Maine, on view at The Met Breuer through June 18, 2017

The Met Store: Marsden Hartley's Maine