Sometimes We Have to Get Used to Things: Luis de Morales's Lamentation

Luis de Morales (Spanish, 1510/11–1586). The Lamentation, ca. 1560. Oil on walnut, 35 x 24 5/8 in. (89 x 62.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alejandro Santo Domingo and Annette de la Renta Gifts; Bequests of George D. Pratt and of Annette B. McFadden, and Gifts of Estate of George Quackenbush, in his memory, of Dr. and Mrs. Max A. Goldzieher, of Francis Neilson, of Dr. Foo Chu and Dr. Marguerite Hainje-Chu, of Mr. and Mrs. Harold H. Burns, and of Mr. and Mrs. Joshua Logan, and other gifts and bequests, by exchange; Victor Wilbour Fund; and Hester Diamond Gift, 2015 (2015.398)

«For visitors who expect Renaissance art to conform to certain standards of ideal beauty, Luis de Morales's painting of the Lamentation—in which the Virgin cradles the dead body of her son in her arms, while Mary Magdalene and Saint John the Evangelist look on tearfully—can be deeply disconcerting. In this scene, on view through March 24 in European Paintings: Recent Acquisitions 2015–16, Christ's head is thrown back in an ungainly fashion, and we see his jagged teeth as his jaw hangs open. The skin of all four figures has a terrible pallor, and the palette, while memorable, is unnatural and icy. The cross itself dominates the center of the composition, and there is no softening landscape behind; indeed, the background is black. At first glance, the painting is mostly disturbing.»

And yet, Morales's contemporaries in Spain called him "El Divino" and were enamored of his difficult yet exquisite religious paintings. For them his work was the visual equivalent of the intensely moving Catholic literature of the day. In both poetry and prose, they expected devotional texts and art to make them feel the pathos of their religion, which included death and loss.

There is a remarkable coincidence between the words used to describe these dramatic sacred events and the images used to depict them, as when one famous set of "meditations" urged the reader to envision the Virgin as clasping "the lacerated body [of Christ] to her breast" as her tears bathe him. [1] Rarely have tears played such a role in painting as here, in which they stream down the cheeks of both Mary Magdalene and Saint John. The importance of tears as a spiritual, purifying gift would take physical form in the next century in the work of great Spanish sculptors such as Pedro de Mena.

Pedro de Mena (Spanish, 1628–1688). Mater Dolorosa (detail), ca. 1674–85. Partial-gilt polychrome wood, sculpture only, confirmed: 24 13/16 x 23 1/8 x 15 in. (63 x 58.7 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, Mary Trumbell Adams Fund, and Gift of Dr. Mortimer D. Sackler, Theresa Sackler and Family, 2014 (2014.275.2)

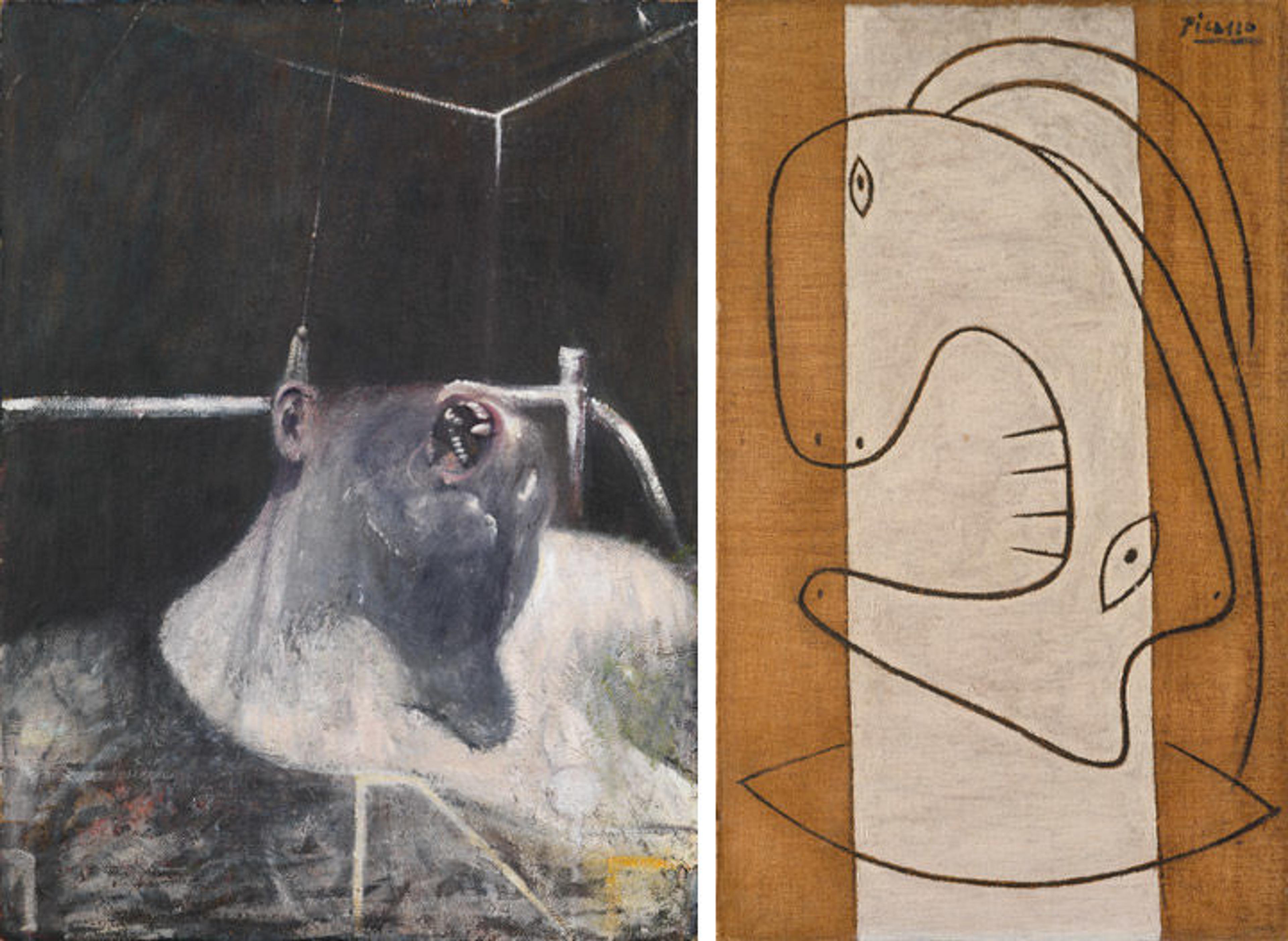

The delicate beauty of the tears of Morales's saints, as well as their curly hair and melancholy faces, provides a moving counterpoint to the harshness of the scene they are witnessing. We also should be accustomed to art that seeks not for commonplace beauty, but instead for the deeply expressive—and we should be intrigued when we find such expression before the modern era. After all, we stop to admire Francis Bacon's Head I, with its similar emphasis on the jarring depiction of a gaping mouth, and we understand Picasso's even more abstract manipulations of the human form for tough, expressive purposes, such as in Head of a Woman.

In all these cases moving away from a sugarcoated beauty leads to something else: human truths.

Left: Francis Bacon (British [born Ireland], 1909–1992). Head I, 1947–48. Oil and tempera on board, 39 1/2 x 29 1/2 in. (100.3 x 74.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Richard S. Zeisler, 2007 (2007.247.1). © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Head of a Woman, 1927. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 21 3/4 x 13 1/4 in. (55.2 x 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, 1998 (1999.363.66). © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Note

Granada, Fray Luis de. "Libro de la oración y meditación" (1586). Quoted in Jonathan Brown, The Golden Age of Painting in Spain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1991.

Related Links

European Paintings: Recent Acquisitions 2015–16, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through March 26, 2017

Now at The Met: View all blog articles related to this exhibition.

MetCollects—Episode 4 / 2015: "Luke Syson on Pedro de Mena's Polychrome Sculptures"

Andrea Bayer

Appointed the Museum’s Deputy Director for Collections and Administration in October 2018, Andrea Bayer was previously the Jayne Wrightsman Curator in the Department of European Paintings. She received her Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1990, and has been on the staff of The Met since that time.

An expert on Italian Renaissance art, she has worked on a range of exhibitions, both thematic investigations—such as Painters of Reality: The Legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy (2004) and Art and Love in Renaissance Italy (2008–9)—and monographic shows on artists such as Giambattista Tiepolo, Dosso Dossi, and Antonello da Messina. Her most recent exhibitions include Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, one of the inaugural exhibitions at The Met Breuer. She was a curator in European Paintings from 2007 to 2018, and, in 2014, became the Jayne Wrightsman Curator. Outside the department, Bayer served as Interim Deputy Director for Collections and Administration (May–October 2018), Interim Head of Education (2008–9), and for six years was coordinating curator for the Curatorial Studies program run jointly by the Museum and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. She is currently co-chairman of the Director’s Exhibition Committee.