How William the Hippo Got His Name

William the hippopotamus. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret I to Senwosret II (ca. 1961–1878 B.C.). Faience. From Egypt, Meir, tomb B3; Said Bey Khashaba excavations, 1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1917 (17.9.1)

«William, the ancient Egyptian hippopotamus, is the beloved unofficial mascot of The Met. Since he came to The Met 100 years ago, this is the perfect occasion to recall how he got this name and to republish the entertaining story that gave him the name in the first place!»

The little hippopotamus figurine was made in Egypt around 1961–1878 B.C. and placed in a tomb to magically guarantee the rebirth of the deceased. Several thousand years passed before it was excavated (in 1910) and became part of The Met collection (in 1917).

The name William is, of course, a modern nickname. It first appeared in 1931 in a story that was published in the British magazine Punch. The author, a certain Captain H. M. Raleigh, wrote that his family owned a framed color print of the Metropolitan Museum of Art hippo and that they had named him "William." As much as he and his wife Margery adored the hippo, they appreciated him even more for his oracular power. Several times they made the mistake of disregarding William's "advice." On one occasion they ignored his disapproval of their summer vacation plans, and lo and behold, the vacation turned out to be a disaster. Raleigh's family consulted William on every important decision thereafter.

The Met republished the Punch story in the Museum's Bulletin of that same year, and the name William caught on!

But since Punch is a humor and satire magazine, one wonders whether this is a true story. Captain Raleigh (Hilary Mason Raleigh, 1893–1969) did indeed exist, and his wife was called Margaret and can thus be identified with the "Margery" in the story. It's also clear from the detailed description of William the hippo that the author must have seen or owned a color image of The Met's hippo. However, Raleigh seems to have been a writer of stories and novels by profession. In fact, the same issue of Punch contains several other stories by him, including one about Wilfred, a live chameleon that his family had supposedly received as a gift, and another about a film crew that is captured by cannibals while shooting a movie involving cannibalism called "Baby I Could Eat You Whole!"

It therefore seems likely that the charming story about William the hippo is largely a humorous fiction, possibly based on some true elements. And today we still use the name that Captain Raleigh chose for The Met's hippo more than 80 years ago―even the current Museum display label reads: "Hippopotamus ('William')."

You can enjoy the full story here:

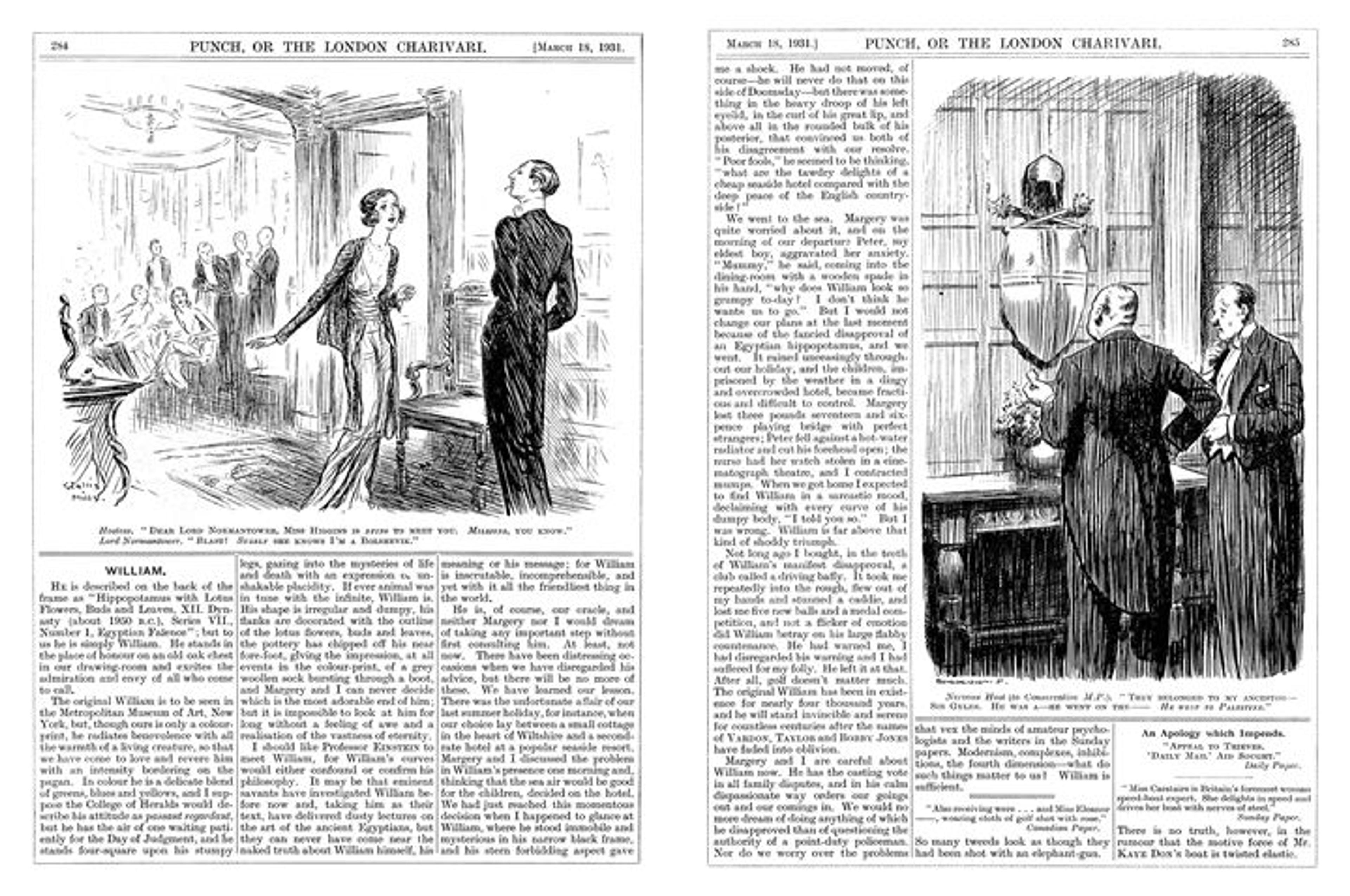

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

March 18, 1931

Reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd.

WILLIAM.

He is described on the back of the frame as "Hippopotamus with Lotus Flowers, Buds and Leaves, XII. Dynasty (about 1950 B.C.), Series VII., Number 1, Egyptian Faience"; but to us he is simply William. He stands in the place of honour on an old oak chest in our drawing-room and excites the admiration and envy of all who come to call.

The original William is to be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, but, though ours is only a colour-print, he radiates benevolence with all the warmth of a living creature, so that we have come to love and revere him with an intensity bordering on the pagan. In colour he is a delicate blend of greens, blues and yellows, and I suppose the College of Heralds would describe his attitude as passant regardant, but he has the air of one waiting patiently for the Day of Judgment, and he stands four-square upon his stumpy legs, gazing into the mysteries of life and death with an expression of unshakable placidity. If ever animal was in tune with the infinite, William is. His shape is irregular and dumpy, his flanks are decorated with the outline of the lotus flowers, buds and leaves, the pottery has chipped off his near fore-foot, giving the impression, at all events in the colour-print, of a grey woollen sock bursting through a boot, and Margery and I can never decide which is the most adorable end of him; but it is impossible to look at him for long without a feeling of awe and a realisation of the vastness of eternity.

I should like Professor Einstein to meet William, for William's curves would either confound or confirm his philosophy. It may be that eminent savants have investigated William before now and, taking him as their text, have delivered dusty lectures on the art of the ancient Egyptians, but they can never have come near the naked truth about William himself, his meaning or his message; for William is inscrutable, incomprehensible, and yet with it all the friendliest thing in the world.

He is, of course, our oracle, and neither Margery nor I would dream of taking any important step without first consulting him. At least, not now. There have been distressing occasions when we have disregarded his advice, but there will be no more of these. We have learned our lesson. There was the unfortunate affair of our last summer holiday, for instance, when our choice lay between a small cottage in the heart of Wiltshire and a second-rate hotel at a popular seaside resort. Margery and I discussed the problem in William's presence one morning and, thinking that the sea air would be good for the children, decided on the hotel. We had just reached this momentous decision when I happened to glance at William, where he stood immobile and mysterious in his narrow black frame, and his stern forbidding aspect gave me a shock. He had not moved, of course—he will never do that on this side of Doomsday—but there was something in the heavy droop of his left eyelid, in the curl of his great lip, and above all in the rounded bulk of his posterior, that convinced us both of his disagreement with our resolve. "Poor fools," he seemed to be thinking, "what are the tawdry delights of a cheap seaside hotel compared with the deep peace of the English countryside?"

We went to the sea. Margery was quite worried about it, and on the morning of our departure Peter, my eldest boy, aggravated her anxiety. "Mummy," he said, coming into the dining-room with a wooden spade in his hand, "why does William look so grumpy to-day? I don't think he wants us to go." But I would not change our plans at the last moment because of the fancied disapproval of an Egyptian hippopotamus, and we went. It rained unceasingly throughout our holiday, and the children, imprisoned by the weather in a dingy and overcrowded hotel, became fractious and difficult to control. Margery lost three pounds seventeen and six-pence playing bridge with perfect strangers; Peter fell against a hot-water radiator and cut his forehead open; the nurse had her watch stolen in a cinematograph theater, and I contracted mumps. When we got home I expected to find William in a sarcastic mood, declaiming with every curve of his dumpy body, "I told you so." But I was wrong. William is far above that kind of shoddy triumph.

Not long ago I bought, in the teeth of William's manifest disapproval, a club called a driving baffy. It took me repeatedly into the rough, flew out of my hands and stunned a caddie, and lost me five new balls and a medal competition, and not a flicker of emotion did William betray on his large flabby countenance. He had warned me, I had disregarded his warning and I had suffered for my folly. He left it at that. After all, golf doesn't matter much. The original William has been in existence for nearly four thousand years, and he will stand invincible and serene for countless centuries after the names of Vardon, Taylor and Bobby Jones have faded into oblivion.

Margery and I are careful about William now. He has the casting vote in all family disputes, and in his calm dispassionate way orders our goings out and our comings in. We would no more dream of doing anything of which he disapproved than of questioning the authority of a point-duty policeman. Nor do we worry over the problems that vex the minds of amateur psychologists and the writers in the Sunday papers. Modernism, complexes, inhibitions, the fourth dimension—what do such things matter to us? William is sufficient.

William the Hippo: Celebrating 100 Years at The Met

#William100

Isabel Stünkel

Isabel Stünkel is an associate curator in the Department of Egyptian Art.

Kei Yamamoto

Kei Yamamoto, former Lila Acheson Wallace Research Associate and now Research Specialist at the University of Arizona, received degrees from the University of Pennsylvania (BA, 2001) and the University of Toronto (MA, 2002; PhD, 2009). As an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at The Met, he participated regularly in the Museum's ongoing archaeological expedition to Dahshur. Kei has also excavated at Abydos and Tell Tebilla in Egypt. Before coming to the Met, he lived in Cairo and worked for the Grand Egyptian Museum Project.