«"Driven by his peculiar temperament, [Caravaggio] gave himself up to the dark manner, and to the expression of his turbulent and contentious nature."

Although written more than 60 years after the artist's death, this view that the darkness of Caravaggio's paintings was an extension of his character had already been voiced in his lifetime. It poses for us today a fundamental problem: To what degree can we associate an artist's style with his personality?» Giovan Pietro Bellori, the author of the quote, had no hesitation, linking even Caravaggio's physiognomy to his manner of painting: "He had a dark complexion and dark eyes, black hair, and eyebrows, and this, of course, was reflected in his paintings."

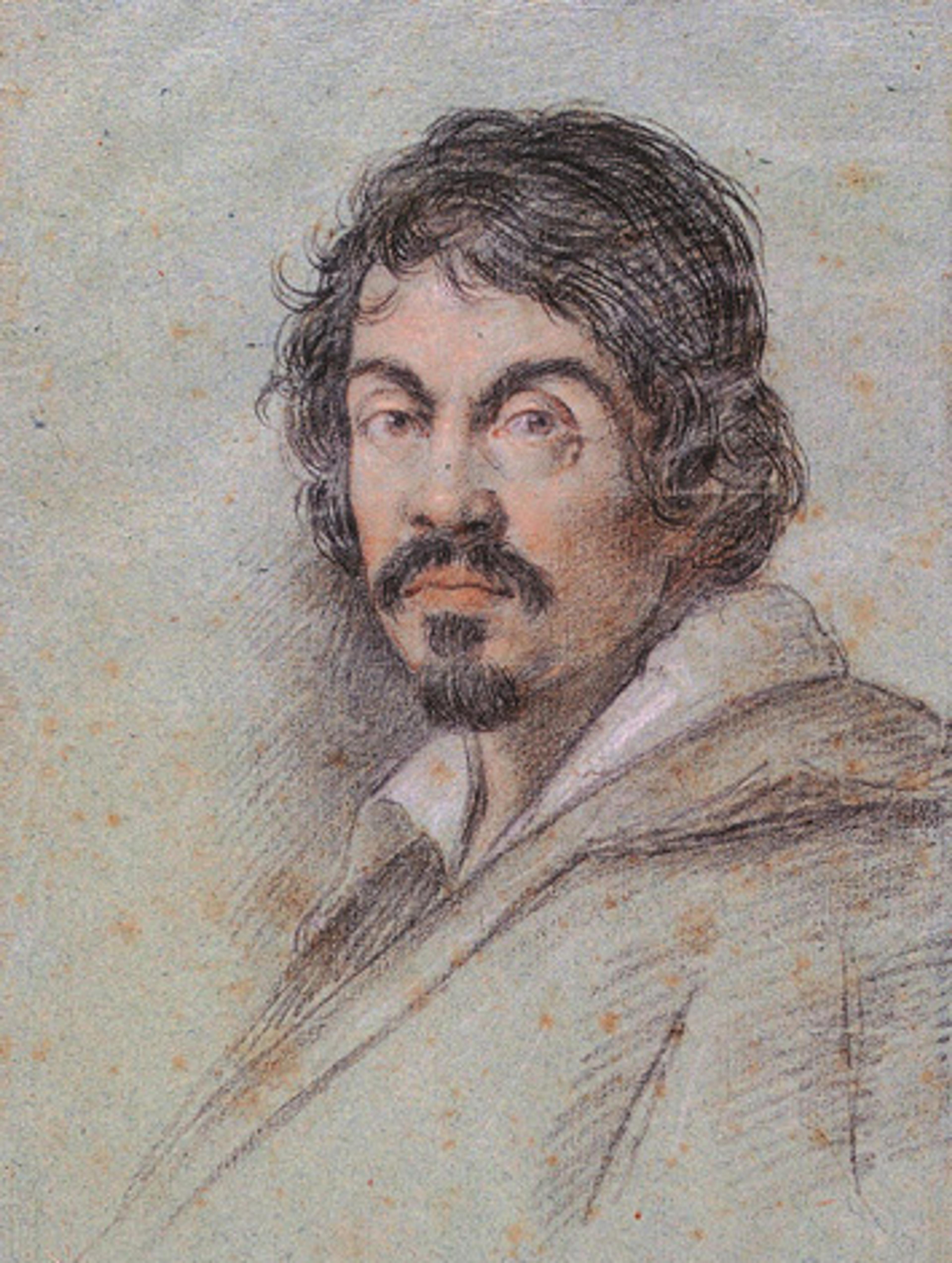

Ottavio Leoni (Italian, 1578–1630). Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, ca. 1621. Biblioteca Marucelliana, Florence. Image via Wikimedia Commons

What cannot be doubted is that Caravaggio's paintings became darker as his career progressed—both in the psychology of the protagonists of his pictures and in the setting of the situations. The Met's great late picture showing the apostle Peter denying that he is a follower of Christ is set in a completely black interior that is relieved only by the very faint mantle of a fireplace. As in a movie still, the spotlight illuminates Peter's face, enhancing the conflicted expression of angered denial and remorse. In some respects, it's like a haunting prelude to the great masterpieces of early cinema and film noir.

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (Italian, 1571–1610). The Denial of Saint Peter, 1610. Oil on canvas, 37 x 49 3/8 in. (94 x 125.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Herman and Lila Shickman, and Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997 (1997.167)

But what about the astonishing Matyrdom of Saint Ursula—a special loan from the Intesa di Sanpaolo in Naples that is now on view at The Met in the exhibition Caravaggio's Last Two Paintings? This murder—for that is what we see here—may just as well have taken place in broad daylight. Caravaggio, however, has staged it in his perpetual night, a darkness that pervades even the noonday sun.

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (Italian, 1571–1610). The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, 1610. Oil on canvas, 56 1/3 x 70 7/8 in. (143 x 180 cm). Intesa Sanpaolo Collection, Gallerie d'Italia—Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano, Naples

Here we see that the Hun king, finding his amorous advances to the virgin Ursula repudiated, has shot her at close range. As in The Denial of Saint Peter, the king's face is wracked by conflicted emotions that contrast in a deeply troubling fashion with Ursula's hands, which frame the exact point of the arrow's penetration. Is the picture not, quite literally, an exploration of the dark regions of the human psyche? No wonder that it is reported that those who saw it were astonished.

Is this darkness as metaphor, or the expression of a tortured, violent artist who, incidentally, has shown himself behind Ursula, straining for a view of the scene? Perhaps it is a bit of both?

Here's what the most famous poet of the day, Giambattista Marino, wrote upon the news of Caravaggio's death, just a few months after the artist painted these pictures:

Death and Nature made a cruel plot against you, Caravaggio:

Nature feared being surpassed by every image you created (created rather than merely painted);

Death burned with indignation because those cut down by his scythe you returned to life, with interest.

Related Links

Caravaggio's Last Two Paintings, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 9, 2017

Now at The Met: "What Is in a Gesture?" (March 28, 2017)