The Scarred Face of Beauty: Rodin and World War I

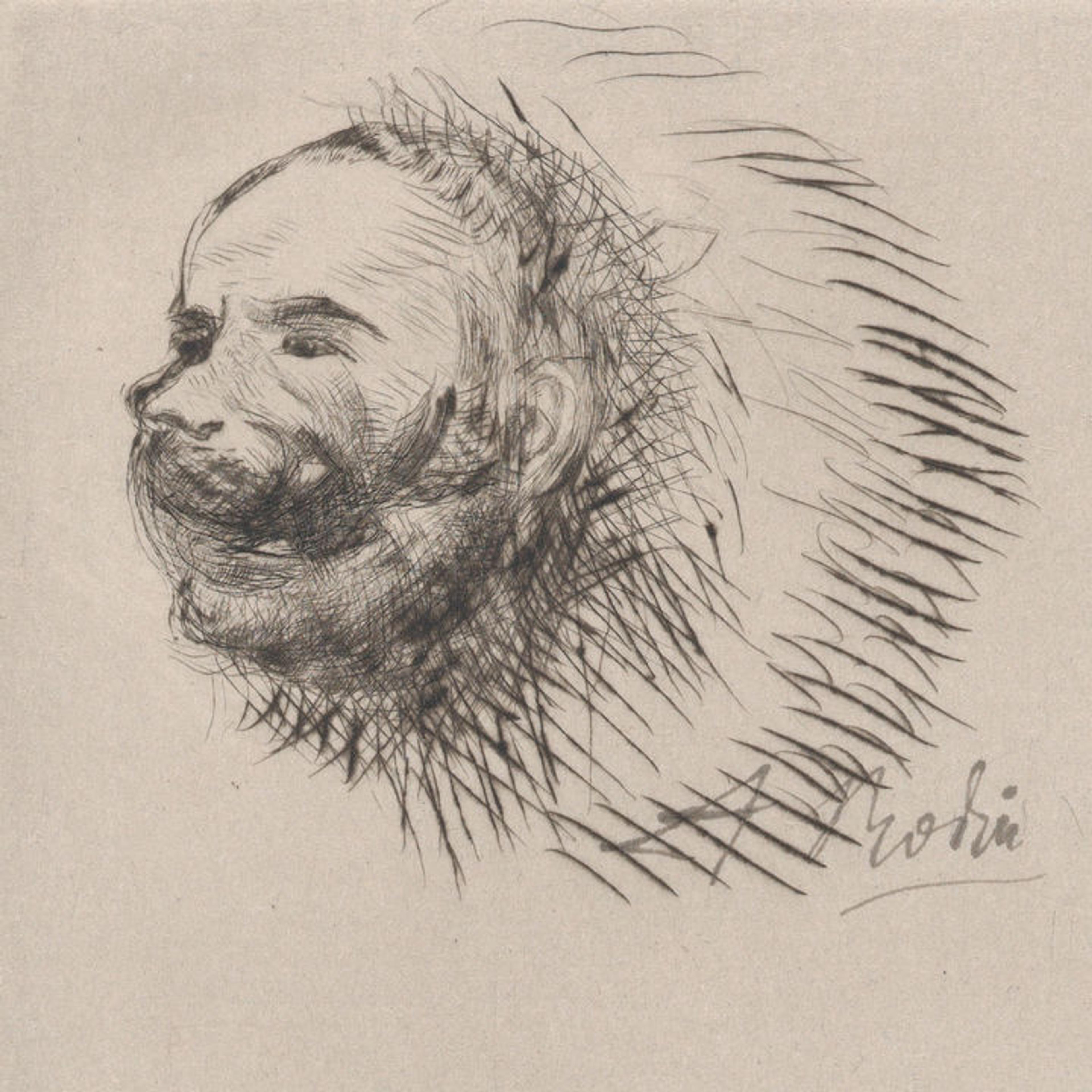

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Contribution receipt of the Special American Hospital in Paris for Wounds of the Face and Jaw (detail), 1916. Drypoint, first state of two, plate: 6 3/4 x 4 3/16 in. (17.2 x 10.7 cm); sheet: 12 3/16 x 9 1/16 in. (31 x 23 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisa Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959 (59.599.48[1])

«One object presently on view in gallery 692 brings together two current exhibitions, each occasioned by centenaries this year: World War I and the Visual Arts and Rodin at The Met. The sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) created this drypoint—a print made by drawing with a needle directly on a copper plate—to serve as an acknowledgement notice for donations to the Special American Hospital in Paris for Wounds to the Face and Jaw in 1916.»

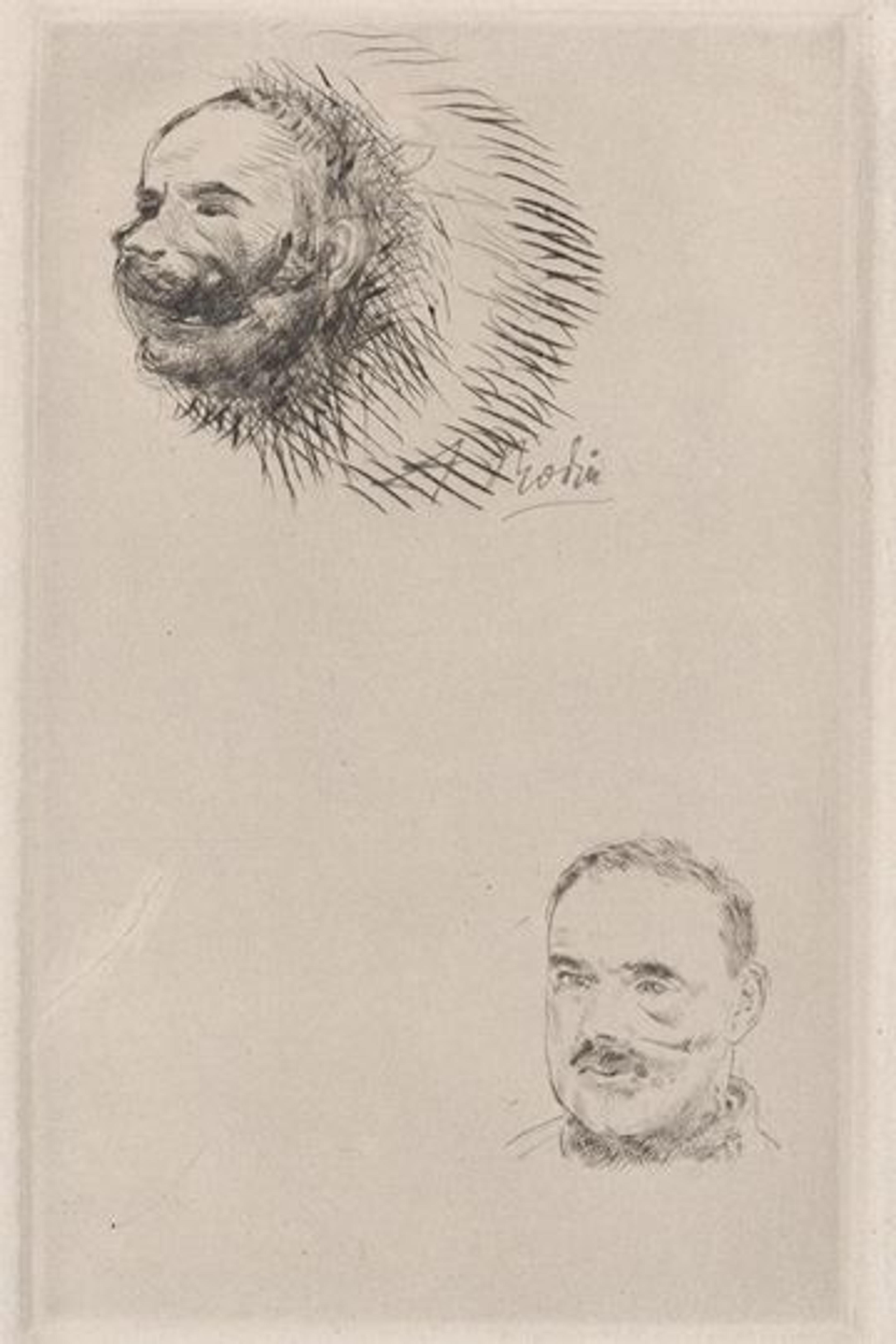

Left: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Contribution receipt of the Special American Hospital in Paris for Wounds of the Face and Jaw, 1916. Drypoint, first state of two, plate: 6 3/4 x 4 3/16 in. (17.2 x 10.7 cm); sheet: 12 3/16 x 9 1/16 in. (31 x 23 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisa Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959 (59.599.48[1])

The Met collection contains impressions of both the first and second (of two) states of this print. The first state, before the addition of text, opposes two heads diagonally on the sheet. The upper left presents a face mutilated by war, in which the vigorously gouged lines evoke the violence wrought upon it. The inky, barbed quality of the printed lines—a result of the ridges formed by the displaced copper, known as the burr—heightens the sense of brutality. (Over time, the burr wears down, which is why its effect is less evident in the second state.) The face at lower right, formed by subtle and neatly organized cross-hatching, represents by contrast the possibilities for reconstruction through specialized surgery. Nevertheless, the visible scarring and asymmetry of the convalescent head serves as a reminder of the lasting effect of these injuries.

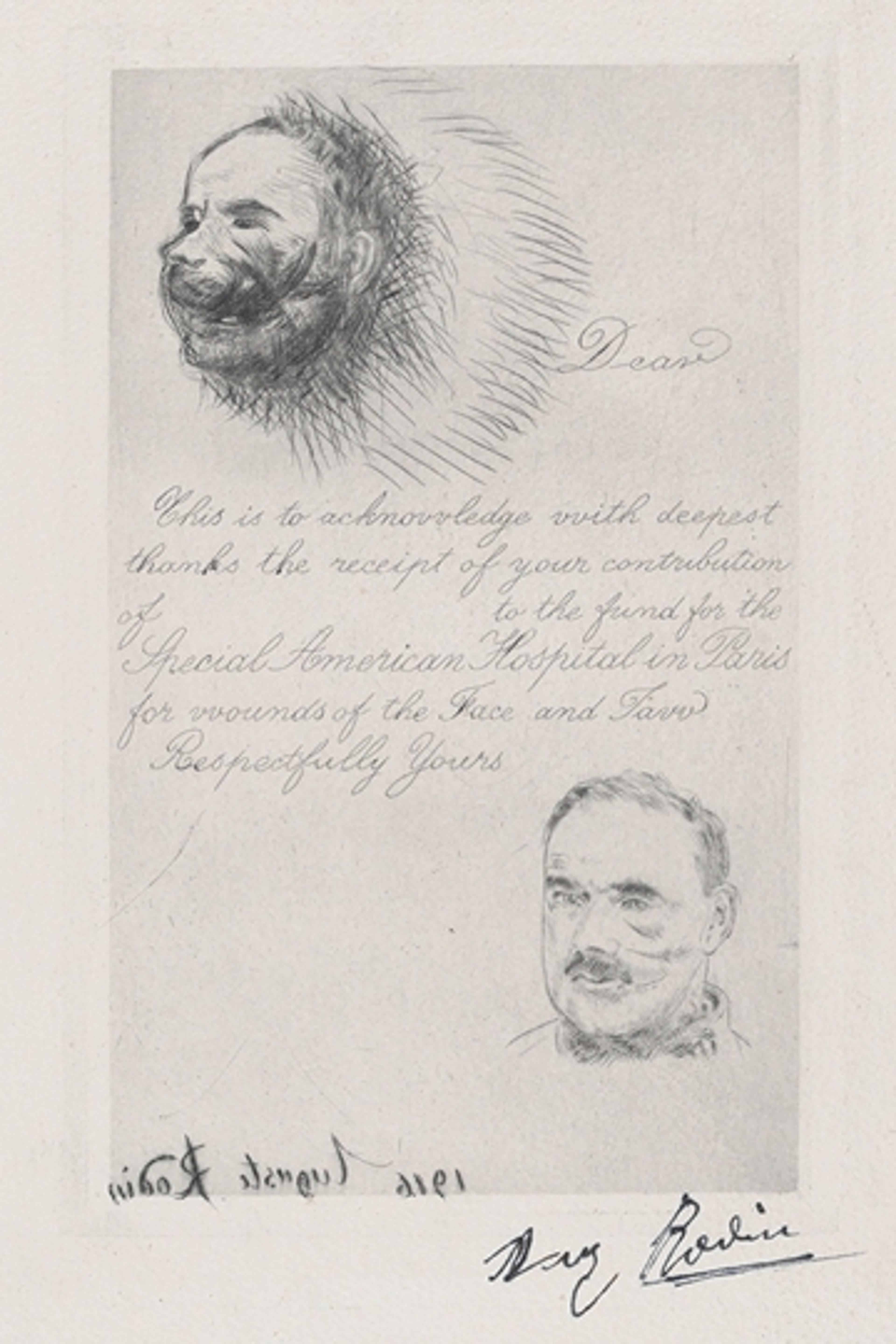

Right: Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Contribution receipt of the Special American Hospital in Paris for Wounds of the Face and Jaw, 1916. Drypoint, second state of two, sheet: 7 x 4 7/16 in. (17.8 x 11.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisa Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959 (59.599.48[2])

The trench warfare and aerial bombardments that defined World War I resulted in injuries on an unprecedented scale. General hospitals in Paris faced such severe overcrowding that they were forced to discharge patients whose wounds were not life-threatening. The committee of American dentists and surgeons established to raise funds for the specialized hospital explained the urgent need: "Noses are blown off; cheek bones crushed, upper jaws caved in and lower jaws shot away, but there is no time for any treatment except to prevent infection." Notably, Dr. Hippolyte Morestin (1869−1919), whose pioneering plastic surgery techniques were exemplary of the hospital's ambitions, was called "the sculptor of human flesh."[1]

Following the outbreak of war, Rodin went to England at the invitation of his friend and later-biographer Judith Cladel. While there, he learned of the bombing of his beloved Reims Cathedral in France. Only a few months prior, in March 1914, Rodin had published a prescient elegy, Les Cathédrales de France (The Cathedrals of France), the culmination of a lifetime of studying the French Gothic monuments.

Right: Auguste Rodin and Charles Morice, Les cathédrales de France (Paris: Armand Colin et Cie., Éditeurs, 1914). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Thomas J. Watson Library (126.6 R61)

Cladel described Rodin's disbelief and shock, "when the second edition of the Daily Mail published an immense reproduction of the [bombed Reims] cathedral, the horror was confirmed. . . . He turned pale as if he was dying, and for two days, white and mute from sorrow, he himself seemed to have turned into one of the statues of the mutilated cathedral."[2] Rodin later expressed his outrage over the enduring impact of war in an interview with the Washington Times, "Germany, through this war, has scarred the face of beauty and the mind of the world with wounds which will never heal."[3]

From London, Rodin went to Rome in November 1914 to stay with John Marshall, then the European purchasing agent for The Met. Marshall had visited Rodin on behalf of the Museum in late 1907 to scout works for acquisition. While in the Eternal City, the sculptor was granted permission to sculpt a portrait of Pope Benedict XV (1854–1922), but His Holiness proved an uncooperative and impatient sitter. After only a few sessions, in May 1915, Rodin took his clay study back to Paris to finish the work there.

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Head of Sorrow, modeled 1882, cast 1963. Bronze, black marble base, overall: 9 x 9 x 10 1/2 in., 11.8 lb. (22.9 x 22.9 x 26.7 cm, 5.4 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift from B. Gerald Cantor Collection, 1985 (1985.386)

The precise circumstances for Rodin's involvement in designing the certificate for contributions to the hospital are yet to be discovered. As an artist whose work conveyed the character of his subjects through their physiognomy, and for whom the expression of human emotion was the utmost goal—as evidenced in a work such as Head of Sorrow—Rodin was undoubtedly sympathetic to the cause. However, it seems the print was never used for its intended purpose; of the 10 known impressions of the drypoint, none are completed with the names of donors. The artist's health declined rapidly in 1916; he fell and suffered strokes in March and July of that year. The shaky signature in ink on the second state in the collection may attest to his deterioration. The hospital ultimately opened on July 3, 1916, in a building near the Arc de Triomphe provided by the French War Office.[4]

Rodin did not survive the war. He died on November 17, 1917, at his home in Meudon. The complications of wartime prevented a state funeral, but Cladel points out what an homage the French government paid to the artist when it negotiated, debated, and accepted the gift of his life's work (the entire contents of his studio, including complete and unfinished sculpture, and thousands of drawings) in the midst of the crisis of war. "Turning its attention for an instant from the necessities of war, from the front where it struggles, suffers, and dies, [France] remains calm enough, sufficiently sure of itself, to offer to one of its heroes of toil, and of the thought which its soldiers defend, a testimony of its gratitude and admiration."[5] These works form the collection of the Musée Rodin today.

Notes

[1] Journal of Allied Dental Societies 10 (1915): 541.

[2] Judith Cladel, Rodin: Sa Vie glorieuse, sa vie inconnue (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1936), 19; cited in RuthButler, Rodin: The Shape of Genius (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 496.

[3] "Whole World Brutalized as Warfare Destroys Art, Declares Sculptor Rodin," Washington Times (January 11, 1915): 3.

[4] "Off for France to Treat Jaw Wounds, Dr. Wheeler Will Sail to Mend the Shattered Faces of French Troops," New York Times (August 4, 1916): 4.

[5] Cladel, Rodin: The Man and His Art, trans. S. K. Star (New York: The Century Co., 1917), 357.

Related Links

Read a blog series on Rodin at Now at The Met.

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 8, 2018

Rodin at The Met, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 15, 2018

See more digital content related to Rodin at The Met.

Ashley Dunn

Ashley Dunn is an associate curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.