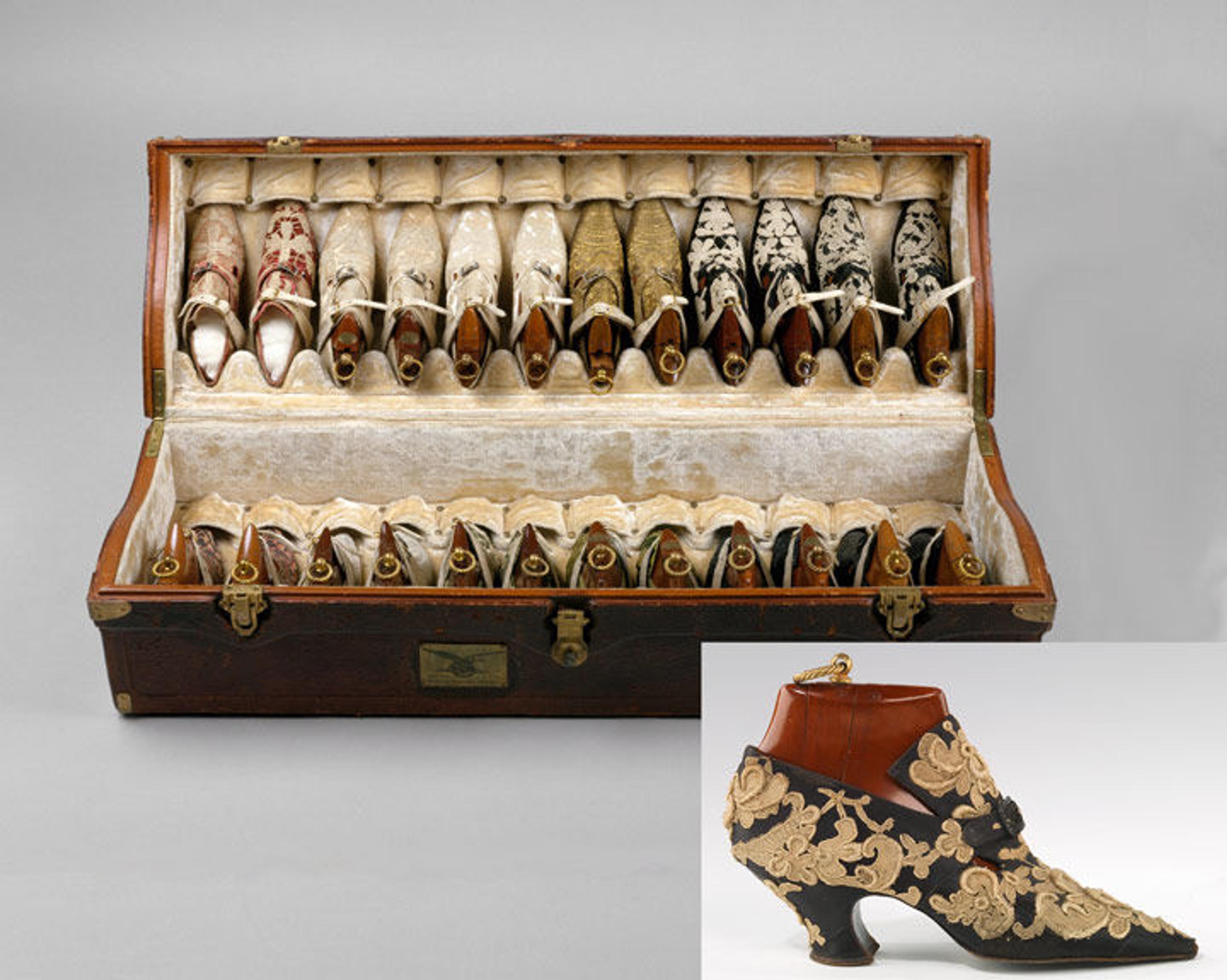

Fig. 1. Pierre Yantorny (Italian, 1874–1936). Trunk and shoes, 1914–1919. Wood, silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Capezio Inc., 1953 (C.I.53.76.26 and C.I.53.76 10-21). Inset bottom right corner: Pierre Yantorny (Italian, 1874–1936). Evening shoes, 1914–19. Shoe: Silk, metal, jet; tree: mahogany and lacquered brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mercedes de Acosta, 1953 (2009.300.1178a and 2009.300.1179a-c)

Even after repeated appearances in exhibitions and publications, two extravagant velvet-lined, leather shoe trunks in The Costume Institute containing a cache of two dozen exquisitely crafted shoes dated to the early 20th century continue to enchant viewers. Resplendent in their individual ivory velvet cradles, the shoes are perfectly supported by fastidiously fitted shoe trees of highly polished wood. Topped with golden twisted-rope pull rings, the shoe trees are as elegant and alluring as the shoes themselves (fig. 1). The mystique of the trunks, shoes, and their shoe trees is heightened by the fact that they were custom-made by the self-proclaimed "most expensive shoemaker in the world," Pierre Yantorny (1874–1936).

Fig. 2. Pierre Yantorny (Italian, 1874–1936). Pair of shoe trees, 1914–1919. Mahogany and lacquered brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Miss Mercedes de Acosta, 1953 (2009.300.1179 a-f)

A number of myths have sprung up over the years about Yantorny and his work; for example, it has been said that these shoe trees were made of wood from old violins personally collected for that purpose by Rita de Acosta Lydig (1880–1929), who was the original owner of The Met's trunks and their contents. Can there be any grain of truth to these incredible claims? Where did this idea come from? And is there, indeed, any genuine relationship between the trees and violins? After Jayson Dobney, curator in the Department of Musical Instruments, confirmed that the trees could not have been made from old, disassembled violins, we were inspired to unravel the mystery further, so we embarked on an in-depth investigation of the trees' construction and delved further into the documentary evidence surrounding the legend.

Here Lies the Myth

Left: Fig. 3. Rita de Acosta Lydig wearing a pair of shoes by Yantorny. Arnold Genthe (American, 1869–1942). Portrait photograph of Mrs. Rita Lydig, 1925. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Arnold Genthe Collection: Negatives and Transparencies, LC-G4085-0365

Both Yantorny and Lydig were ripe candidates for inspiring myth. Yantorny's exorbitant prices, exclusivity, demanding requirements for minimum order, as well as his idiosyncratic technique for examining his clients' feet and his time-consuming, perfectionistic craftsmanship, fixed his elitist position in the public imagination. Lydig's extravagant lifestyle, enhanced by a singular drive for artistic perfection, prompted the artist John Singer Sargent to declare her "a living work of art." Her eccentric wardrobe included quantities of garments made from 17th- and 18th-century laces and lace-covered shoes by Yantorny to match. Lydig's unlimited resources, beautifully shaped feet, and perfectly calibrated gait epitomized Yantorny's ideal client, and she soon became one of his most important, purportedly owning over 150 pairs of his shoes (fig. 3).

The violin myth first appeared in print in 1940 in the checklist of a catalogue for the Museum of Costume Art's (now The Costume Institute) exhibition Appreciations of Rita de Acosta Lydig, in which the trees are described as being made of "violin wood." Although the source of this information is not known, it was likely Rita's sister, Mercedes de Acosta, who loaned them to the exhibition. The highly regarded editor of Vanity Fair, Frank Crowninshield, then reiterated the story in a Vogue article in May of that same year. Cecil Beaton repeated it in his 1954 classic treatise on 20th-century fashion, The Glass of Fashion, adding the twist that Lydig herself had collected the violins. The final codification came from Mercedes' 1960 memoir Here Lies the Heart, in which she wrote: "Rita bought old violins and he [Yantorny] transformed them into shoetrees [sic] so exquisite that they are works of art in themselves."

Here Lies the Truth

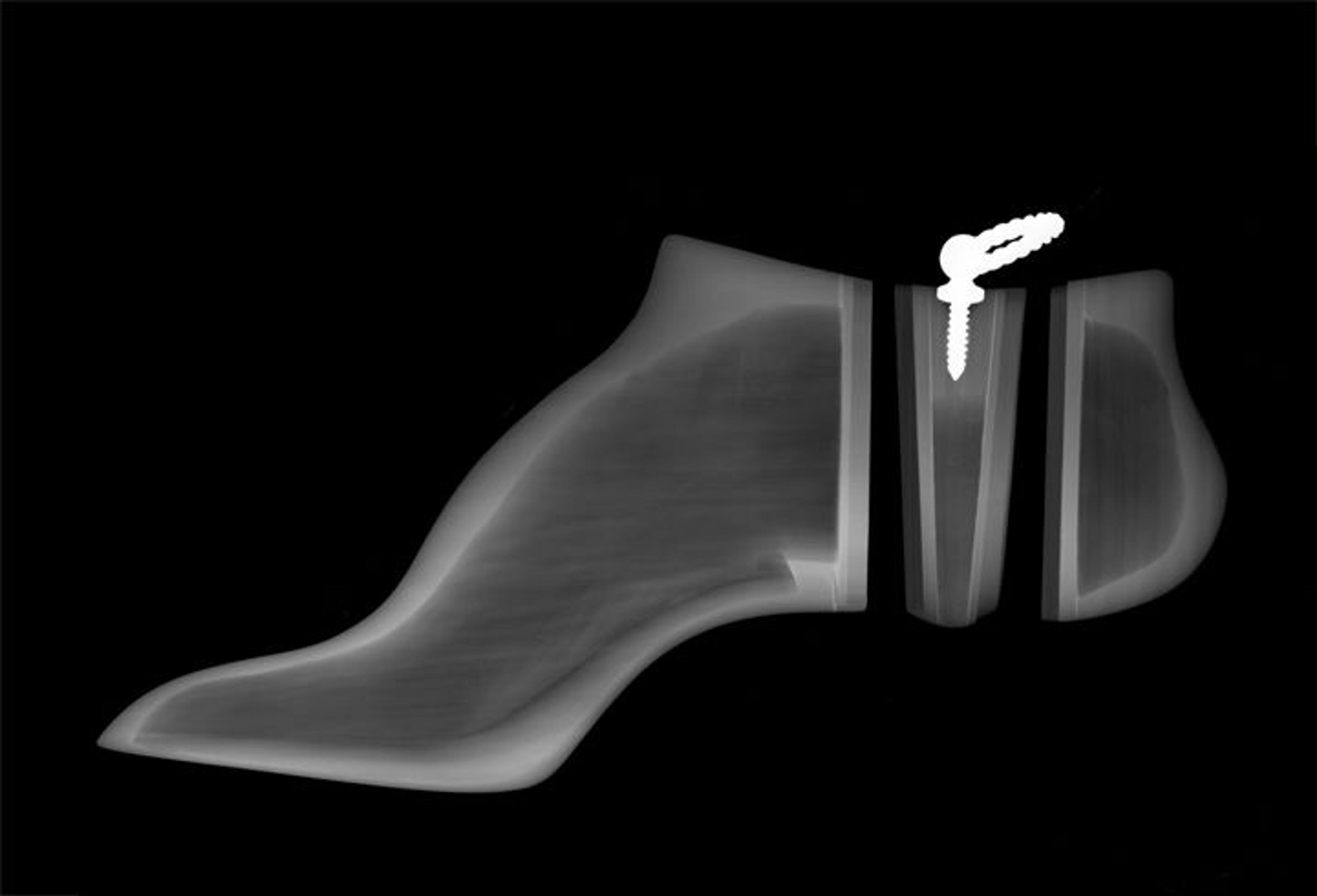

How were these individually sculpted shoe trees actually made? A close look revealed the wood to be mahogany. The continuous woodgrain in each of the three interlocking sections—connected by tongue and groove joints—makes each piece appear solid; however, the fine join lines and feather-light weight gave away that each element had been hollowed out, a feature that was confirmed with radiographs (figs. 4, 5).

Top: Fig. 4. The three mahogany pieces forming the shoe tree have fine glue joints. Bottom: Fig. 5. The radiograph of a shoe tree shows that the wood is hollowed out. Images by Mechthild Baumeister

To get started, Yantorny prepared six pieces of matching mahogany for each pair of shoe trees. He selected a block of mahogany with horizontal grain direction for the largest section in the front and a vertical grain direction for the center and heel pieces. His next step must have been to transfer the specific outline to each piece of wood, which he then roughly cut to shape. In order to hollow out the front piece, he made two saw cuts: first a straight cut parallel to the vertical plane and a second one parallel to the sole, together providing access from the back and bottom. While only one vertical saw cut was made to hollow out the heel piece, the center piece was sawn along both sides, and enough wood was left in place to accommodate the threaded shaft that secures the lacquered brass ring.

Fig. 6. The radiograph of a front section reveals that the mahogany is hollowed out with a drill, using a bit with a center point and finished with carving tools. The glue joints are clearly visible (the nails were added during a later repair). Image by Mechthild Baumeister

The radiographs, especially of the front and heel pieces, show varying wall thicknesses and reveal that the cavity was made with a drill using different size bits (fig. 6). The smooth, slightly undulating inner surfaces indicate that the interior was finished with carving tools. The 360-degree radiograph of the front piece clearly reveals that a wooden "bridge" connecting the outer and inner wall at the bottom corners was left in place, providing structural support and additional surface area for the glue that was used to attach the sole.

Fig 7. An animated radiography of the front piece of a shoe tree. Video by Bryan Whitney

After the pieces were glued together, the individual sections must have been shaped to their final forms and the tongue and groove joints cut for a perfect fit, allowing the tapered center piece to be slid in last to make sure that the shoe tree conformed to the inside of the shoe it was made for.

Fig 8. Yantorny in his workshop, 1912. He is holding the handle of a large knife that he used for the rough cutting of his lasts (one of which he holds in his other hand)—which were made of light colored hardwoods such as beech, maple, and hornbeam—and possibly also for shaping the shoe tree sections. There are several braces with drill bits as well as augers hanging on the wall that were used in the hollowing out process as evidenced by their tool marks visible in some radiographs of the shoe trees. Of interest is the stock stored on the top shelf in Yantorny's studio, which might be prefabricated center pieces of the shoe trees with a tongue and groove already in place. Photographer unknown, ca. 1912. Courtesy of M. Jean Schoumann

Returning to the oft-repeated tale that the shoe trees were made from old violins, the technical investigation shows they were made from scratch. Furthermore, violins are traditionally made of maple and spruce, not mahogany. However, there are some parallels that might have fed the myth: Violins are hollow and partially carved out of solid wood, and they also have a glossy finish. Research on historic shoe trees indicates that the construction of Yantorny's trees are likely unique to him. Therefore, while the myth that the shoe trees were made of violins has been debunked, other questions still remain about these virtuosic creations.