Now on View: Shakespeare through the Eyes of Artists

«To mark the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare's death, on April 23, a group of 21 drawings, prints, and illustrated books are now on view in the Robert Wood Johnson Jr., Gallery. This selection of British, German, Swiss, Russian, and American works demonstrates the Bard's broad influence on the visual arts from the 18th century into the modern era.»

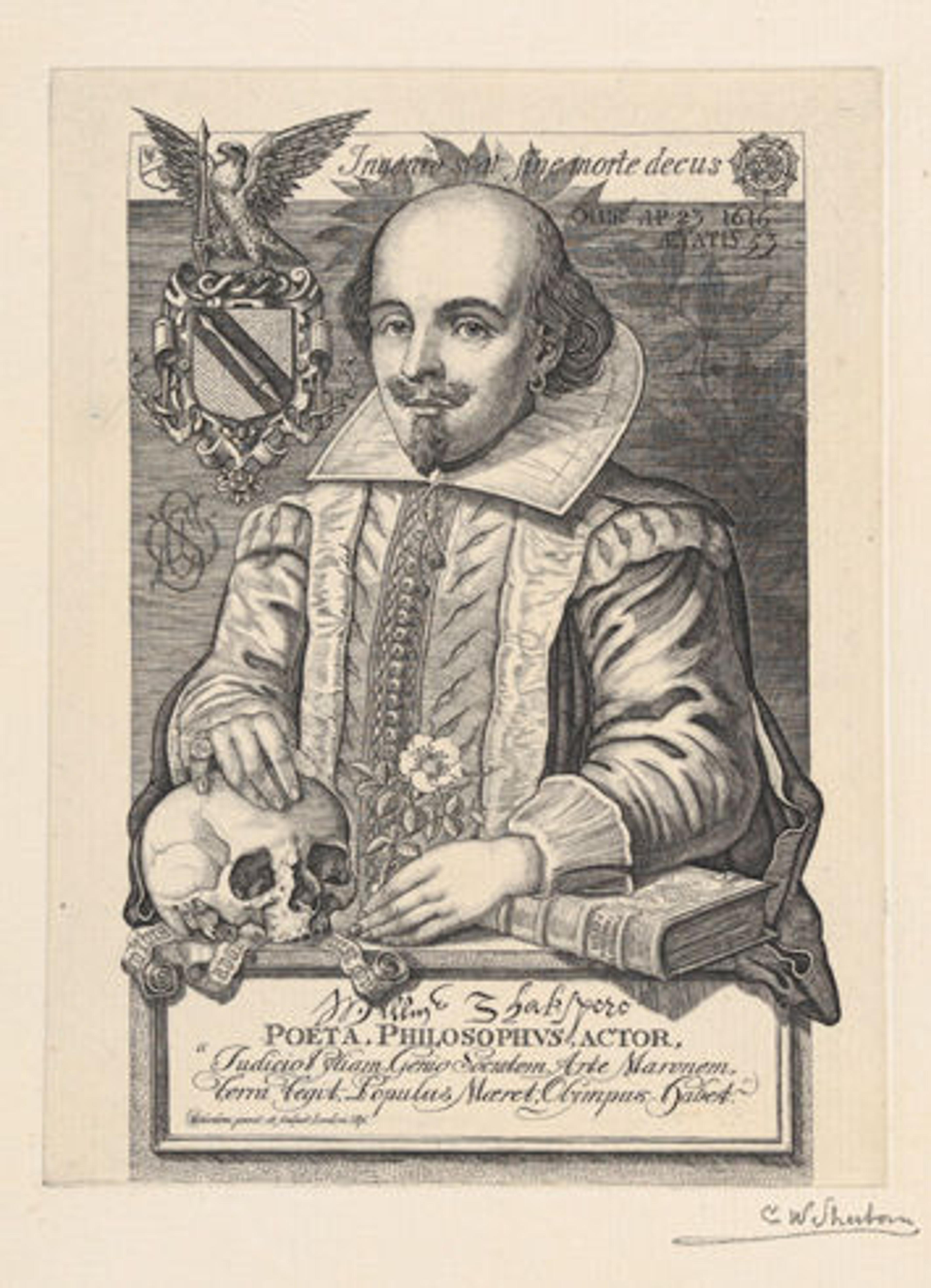

Left: Fig. 1. Charles William Sherborn (British, 1831–1912). William Shakespeare, 1876. Engraving; sixth state of nine; Plate: 6 3/16 x 4 5/8 in. (15.7 x 11.7 cm); Sheet: 12 1/16 x 8 15/16 in. (30.7 x 22.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917 (17.3.569)

Shakespeare's written corpus is daunting—at least 37 plays plus 154 sonnets—of which most of us have read just a handful, and encounter occasionally on the stage or screen. Visual images offer a wonderful way to re-engage with his work, since artists tend to focus on a single moment or passage that stimulates their imagination to produce an image that stands as an independent creation. When we contemplate such works as viewers, we naturally reflect on the related texts and decide if we agree with the artist's vision.

For someone so famous, Shakespeare's own visage is surprisingly hard to pin down; there are only three portraits created during or just after his lifetime that are now thought to have a good claim to authenticity. Of the many portrait prints in The Met collection, one stands out: an engraving by Charles William Sherborn (fig. 1). Based on a memorial sculpture in All Saints' Luddington, part of the Parish of Stratford-upon-Avon, this jewel-like work brings that rather grave original to life.

The subject's eyes glint with intelligence, suggesting a mental dialogue with the surrounding emblems—including a skull that reminds us of his mortality and points to the famous graveyard scene in Hamlet, and a Tudor rose symbolizing transient beauty, recalling Juliet's remark that "a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." Perhaps Sherborn also intended a sly reference here to the debate, already current in 1876, about whether the historical figure of Shakespeare actually was the author of the poetry and plays attributed to him.

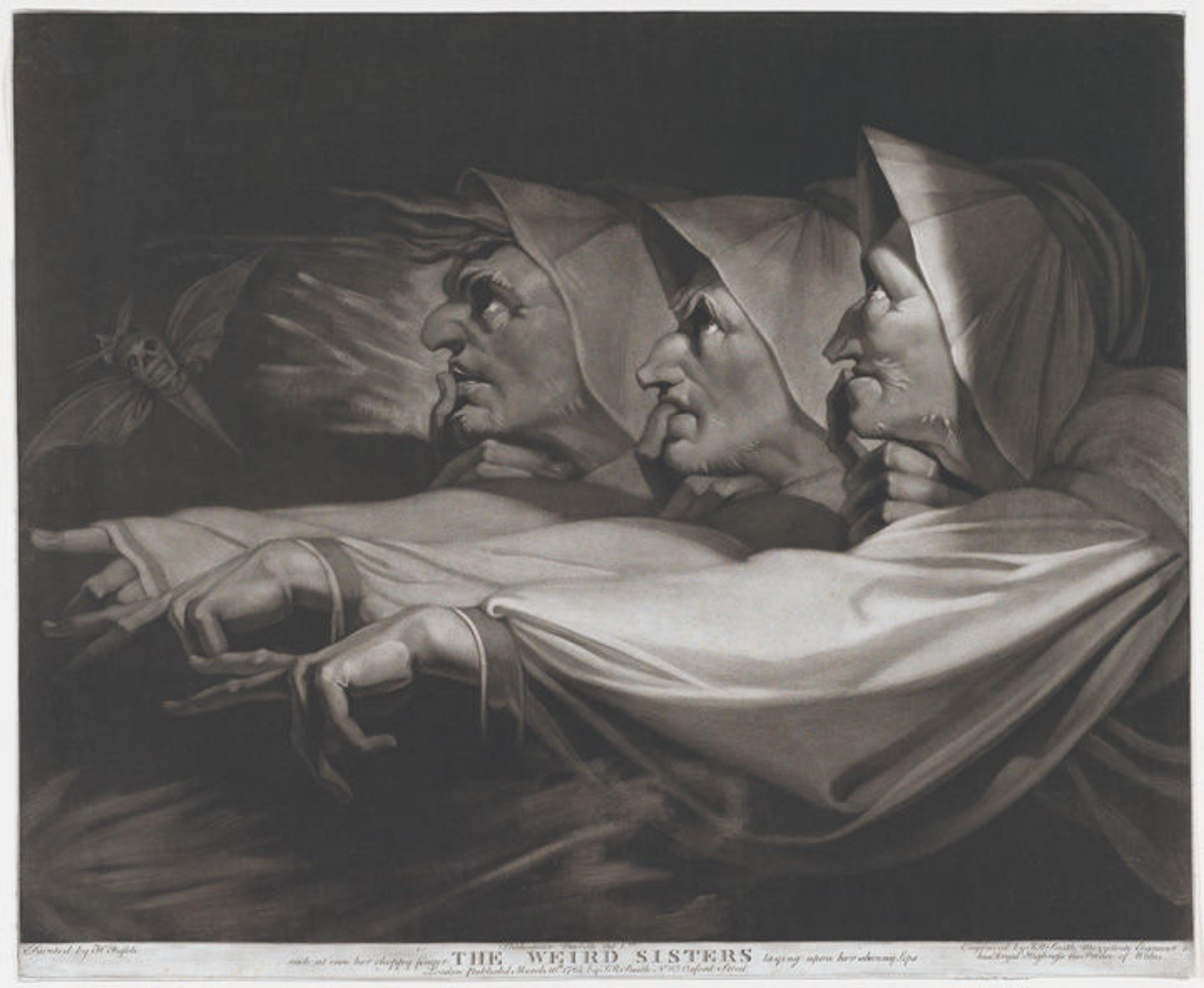

Fig. 2. John Raphael Smith (British, 1751–1812) after Henry Fuseli (Swiss, 1741–1825). The Weird Sisters (Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 1, Scene 3), 1785. Mezzotint; Sheet: 18 1/16 x 21 7/8 in. (45.8 x 55.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959 (59.570.361)

Two contrasting pairs of works inspired by Macbeth and Hamlet offer Now at The Met readers a foretaste of the current exhibition. John Raphael Smith's moody mezzotint of the witches in Macbeth (fig. 2) is based on a 1783 painting by the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli. In act 1, scene 3, Macbeth and Banquo encounter these sinister figures who "look not like the inhabitants o' the earth" on the heath, and their predictions tempt Macbeth into a fatal course of action. Enamored of Mannerist and Baroque art, Fuseli combined bizarre elements similar to those he admired in Salvator Rosa and Domenico Veneziano, but arranged the forms to recall a classical frieze.

Fig. 3. William Blake (British, 1757–1827). Pity, ca. 1795. Relief etching printed in color, finished with pen and ink and watercolor; Sheet: 16 5/8 x 20 3/4in. (42.2 x 52.7cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Robert W. Goelet, transferred from European Paintings, 1958 (58.603)

Around 1795, one of Fuseli's contemporaries, William Blake, responded in a profoundly different way to Macbeth. His image was inspired by lines from act 1, scene 7, where Macbeth imagines the horrible aftermath of his intended murder of King Duncan. A poet himself, Blake focused on Shakespeare's similes and embodied the following lines:

And pity, like a naked new-born babe

Striding the blast, or heaven's cherubin, hors'd

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye . . .

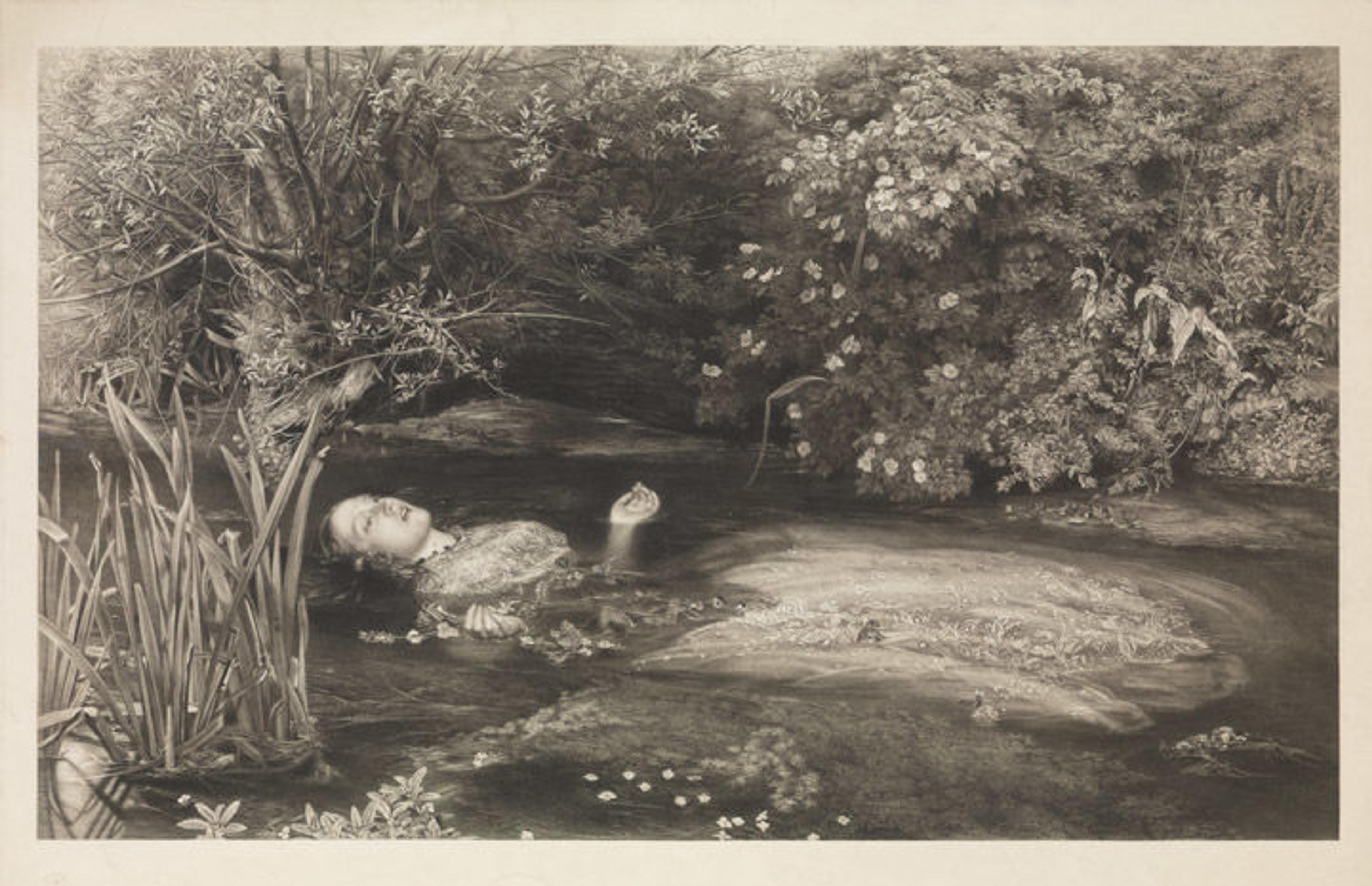

Fig. 4. James Stephenson (British, 1808–1886) after John Everett Millais (British, 1829–1896). Ophelia (Hamlet, Act 4, Scene 7), 1866. Mezzotint, etching and stipple on chine collé; proof; Image: 20 11/16 in. x 34 in. (52.5 x 86.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.40.282)

John Everett Millais's famous image of the death of Ophelia in Hamlet was also inspired by an evocative description, in this case spoken by Queen Gertrude in act 4, scene 7, rather than a staged scene. To create this dense, verdant setting, the artist worked out of doors for months, then posed the model, Elizabeth Siddal, in a bathtub in his studio to complete the painting, which was exhibited in 1852. The hyper-realistic detail and collapsed space initially unsettled viewers, but by the time James Stephenson's engraving (fig. 4) was published in 1866, the conception was admired.

Edward Gordon Craig's minimalist woodcut rendering of Hamlet listening to a mysterious whisperer (fig. 5) offers a distinctly different response to the play. Craig, who worked first as an actor before moving into stage design, created this print as he developed a visionary new production for Constantin Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theatre. For that staging, in 1912, Craig divided the ghost into two distinct beings: a skeletal representation of Hamlet's murdered father for act 1; and the androgynous daemon seen here, a sinister alter ego who entices the prince toward death later in the play.

Left: Fig. 5. Edward Gordon Craig (British, 1872–1966). Hamlet and Daemon (Shakespeare's Hamlet), 1909. Wood engraving; Image: 9 5/16 x 3 3/4 in. (23.7 x 9.5 cm); Sheet: 18 5/8 x 10 1/4 in. (47.3 x 26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.65.2)

The Met collection offers a wonderfully rich range of Shakespearean images that extend well beyond those presently on view. The Department of Drawings and Prints has thus far identified nearly 300 works relating to the Bard, all of which are available for examination on the Museum's website, so be sure to explore and discover your own favorites!

Related Link

Drawings and Prints: Selections from the Permanent Collection, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 18, 2016

Constance McPhee

Curator Constance C. McPhee is responsible for British drawings, prints, and illustrated books before 1900, and pre-twentieth-century American prints, illustrations, and books. After joining the department as print room supervisor in 2000, she organized the New York venue of Samuel Palmer (1805–1881): Vision and Landscape (2005) and co-curated Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine (2011–12) and The Pre-Raphaelite Legacy: British Art and Design (2014). Constance received her BA from Princeton University and an MA and PhD from the University of Pennsylvania.